-

✴along Via XX Settembre on the left (illustrated here) to Porta San Giacomo; and

-

✴along Largo Carducci and Corso Cavour on the right to Porta Romana.

Everything in front of you as far as the city walls belongs to the Terziero Superiore (see Walk I): everything behind you, including the buildings on the other three sides of Piazza della Repubblica, belongs to the Terzieri Mediano or the Terzieri Inferiore.

Palazzo Comunale Palazzo Orfini and Palazzetto del Podestà

Ex-Palazzo Comunale

On the long side of Piazza della Repubblica, opposite the Palazzo dei Canoniche are four public palaces of Foligno, all of which were beautifully restored after the earthquake of 1997. From left to right, these are:

-

✴Palazzo Comunale, the neoclassical facade of which was built in 1835-8, after the earthquake of 1832;

-

✴Palazzo Orfini, which passed to the Orfini family in 1497, but which was reintegrated into the public complex in 2009 and now houses the Museo della Stampa (which extends into the palaces to the right);

-

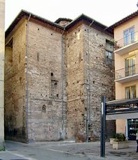

✴ex-Palazzo Comunale; and

-

✴the so-called Palazzetto del Podestà, the oldest part of the complex, dating to the beginning of the Commune in the late 12th century.

-

“[In 1253,] when the Perugian army laid siege to Foligno for seven weeks and diverted the river towards Spello, water appeared in the well in the platea veteris, outside the Duomo. When the army withdrew and the river returned to its original course, the water in this well disappeared” (my translation).

Thus it seems that this well was already barely functioning (at least without divine assistance) by the middle of the 13th century.

Via Colomba Antonietti Exit from piazza, along Via Gramsci

Note the following Roman remains (as discussed in my page Roman Walk II):

-

✴a wall on the right of Via Colomba Antonietti, the street under the open archway in the façade of Palazzo Comunale (illustrated above, on the left); and

-

✴a Roman block embedded at the righthand corner of Palazzetto del Podestà, where Via Gramsci enters the piazza.

The south side of Piazza della Repubblica is closed by Palazzo Trinci, the "domus novas magnifici” (magnificent new house) that Ugolino Trinci built in the late 14th century. This was the palace of the Trinci lords of Foligno until the execution of the last of them, Corrado Trinci, in 1439, from which point it accommodated a series of papal governors. The neoclassical facade (1842-7), which was built after the earthquake of 1832, masks the palace’s heterogenous architectural history.

Ugolino probably built the two corridors that linked the palace with adjacent buildings:

-

✴one, which was demolished in the 18th century, spanned what is now Via Gramsci on the left, to Palazzetto del Podesta; and

-

✴the other, which still survives, spanned what is now Via XX Settembre on the right (illustrated here) and continued behind the minor facade of the Duomo to Palazzo delle Canoniche. Part of this corridor can be visited from the palace and part of it is now incorporated into the Museo Diocesano.

-

✴the Pinacoteca Civica;

-

✴the Museo Archeologico; and

Turn left at the foot of the stairs and cross the main courtyard into the subsidiary courtyard beyond it. The modern building to the right houses the public library: before its construction after the Second World War, the walls of the palace behind you and to your left opened onto Piazza del Grano. Laura Lametti (referenced below, at pp. 55-6) described an ancient wall incorporated into the wall behind you (behind the two later arches) as:

-

“... a unique element, which we do not find elsewhere: a massive wall that extends along almost the entire length of [the southwest] wing and seems to turn and then continue for a short way towards the northwest. The wall reaches to roughly the level of the existing ground floor. Recently, the interesting hypothesis has been [formulated graphically as Figure 48 by Vladimiro Cruciani, referenced below] according to which this stretch of wall could have belonged to primitive walls of the nascent medieval town of Fulgineum” (my translation).

In Cruciani’s Figure 48, this primitive circuit is labelled “primo perimetro”. This refers to the walls of the castrum that was mentioned in an account by Sigebert of Gembloux of the theft of the relics of St Felician in 970: these relics were then ‘ipso intimo antro’ (in a very deep cavern) at ‘Fulinias [sic], castrum non procul a Spoleto’ (Fulginia, a castrum not far from Spoleto).

The following short detour takes you along Via Antonio Gramsci.

We shall return to this an important street later in this walk.

The objective of the present detour is to introduce you to the church of Sant’ Apollinare, which might have been important in the recovery of this area after the devastation of the Gothic War (535-54).

Facade of Sant’ Apollinare Rear of Sant’ Apollinare

Via Gramsci Piazza del Grano

The ex-church of Sant’ Apollinare, which stands at the back of the piazza, was first documented in 1129. However, as described in this link, scholars have recently suggested that its location and, in particular, its dedication, suggest an ancient foundation:

-

“The diffusion in Italy of the cult of Sant’ Apollinare occurred ... in the 6th century, with the ‘Byzantine’ domination, to the point of becoming emblematic of Byzantine presence and hegemony in the west. In Umbria, it was widely diffused, thanks in part to the channels of communication between Rome and Ravenna represented by Via Amerina and Via Flaminia. This supports the hypothesis of the presence here of a strategically placed fortress that housed this cult site dedicated to St Apollinaris of Ravenna, which had been founded following the Byzantine reconquest [in 554] and which resulted in the urban settlement of the area around the fortress itself” (my translation).

If this is correct, this was the development that nucleated the rebuilding of the area outside the castrum, around which you are about to walk.

Return to Palazzo Trinci, where the detour ends.

Leave Piazza della Repubblica along Via XX Settembre. This street, which is named for the day in 1870 that soldiers of the new Kingdom of Italy entered Rome, was laid out in 1880 to a plan by Vincenzo Vitali.

Take a short detour by turning right, along Via dell’ Oratorio:

-

✴The apse of the Duomo, which was rebuilt in 1457-62, is on the right: you can see the vestiges of its original window.

-

✴The remains of a wall of the old Palazzo Vescovile can be seen beyond it: this palace was demolished in ca. 1565 to make way for a new sacristy.

Return to Via XX Settembre. The entrance to the Palazzo Elisei (now a shopping centre) is at number 14 on the right, with Via Elisei just beyond it.

-

“...at numbers 52 and 47 [marked on the photograph], adjacent to Porta Strettura, [buildings that] had large Roman blocks reused in their bases (like almost all of the towers of the city) ...’ (my translation).

Ludovico Jacobilli (quoted by Guerrini and Latini in entry 105), who was writing in the 17th century, recorded that the gate was built:

-

“... of ancient stones, with a tower above, at the end of the street named Strettura, ... not far from the Ponte di Cesare, now called Ponte della Pietra ...” (my translation).

(The Roman remains here are as discussed in my page Roman Walk II).

Reconstruction of Ponte Cesare by Luigi Crema (from G. Dominici, referenced below, p. 31)

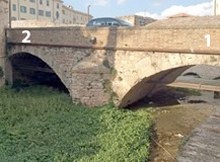

Only the first arch is visible (the arch to the right in the photograph below)

Continue to the bridge and look back under it: the Topinello runs under the church. Karl Schubring (referenced below) placed another gate in the early walls here, which he identified as the Porta Sancte Margarite, which had apparently been documented in 1291.

Cross the bridge and take a short detour by continuing ahead (still on Via Santa Margherita) to see Palazzo Barnabò, at number 26-8 on the right.

Return to the bridge and turn left along the Portici delle Conce (the medieval porticoes that belonged to the tanneries along the canal), along the left bank of the Topinello. Continue as far as the pedestrian bridge. Unfortunately (as at 2016), the way ahead is blocked, so you have to take a detour:

-

✴Cross the bridge and look to your left to see the back of the mill (the so-called Mulino di Sotto) across the Topinello that is your destination at the end of the detour.

-

✴Continue across the car park and the road ahead, and turn left along Via Giovanni Pascoli.

-

✴Walk into the next car park on the left and cross it diagonally, taking the marked ‘uscita’ (exit) at the far right corner.

This brings you to the side of the Mulino di Sotto, and you can now look back along the closed section of the Portici delle Conce. According to Vladimiro Cruciani (referenced below, at p. 29), the houses here were built on a second stretch of walls along the Topino.

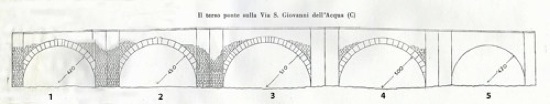

Reconstruction of Ponte di S. Giovalli dell’ Acqua by L.Crema (G. Dominici, referenced below, p. 31)

Arch 5 no longer survives, but its original existence is suggested by the symmetry of the arrangement

Via San Giovanni dell’ Aqua crosses the Topinello here: the bridge, which was recorded as the ‘pontis sancti Iohnnis ab aqua’ in 1277, is still called Ponte di San Giovanni dell’ Acqua. To see it, cross the street and walk through the entrance posts at number 15:

-

✴Two of its arches (illustrated above, on the right) can be seen protruding from under the entrance wall of the Giardino Giusti Orfini, (see below).

-

✴Another two arches survive under the entrance wall itself [visible from inside the park ??].

The arch to the left in the photograph above, which is slightly higher than the others, was probably the middle arch of an original five. As discussed in the link above, some scholars believe that this was originally a Roman bridge while others insist that it was built in the 13th century. This is another of four bridges across the Topinell that is the subject of a scholarly debate as to its possible Roman origins (as discussed in my page Roman Walk III).

Continue to the junction with Via Isola Bella (on the left) and Via Giovanni Pascoli (on the right). The former is named for the suburb of Isola Bella(the beautiful island) which was described in a notarised document of the 10th century as “inter duos pontes” (between two bridges):

-

✴the Ponte di San Giovanni dell’ Acqua (above) would have been one of this bridges; and

-

✴an arch that was unearthed during construction work at this junction suggests that this was the location of the second.

A lady called called donna Bonafemina made bequests for work on a number of bridges, including:

-

✴the “pontis sancti Iohnnis ab aqua”, in 1277; and

-

✴the “pontis sancti Claudi” (Ponte di San Claudio), in 1282.

I think that these were the bridges that were respectively to the southeast and northwest of the Isola Bella, the latter being named for the church of San Claudio (below).

There is a lovely stretch of the Topino ahead. The 14th century wall ran along what are now Via Madonna delle Grazie (to the left) and Via Francesco Ciri (to the right). This was the site of Porta San Claudio, which opened onto the Ponte Nuovo di San Claudio, a bridge over the river that was demolished in 1635. [When was the gate demolished ??]

If you do not want to do the following circular detour, retrace your steps along along San Giovanni dell’ Acqua to the junction with Via Isola Bella and Via Giovanni Pascoli.

The following optional circular walk takes you to see the site of the last bridge

on the Topinello to be described in this walk.

Follow Via Madonna della Grazie as it swings to the left, away from the Topino and becomes an elevated street with a lower car park on the right. Take the steps on the left down to the underpass (on the left) that takes you into car park.

Reconstruction of Ponte di Cippischi by L.Crema (G. Dominici, referenced below, p. 31)

Arch 3 no longer survives, but its original existence is suggested by the symmetry of the arrangement

-

✴Two of what were probably originally three arches of this bridge survive, one of which (illustrated here) now spans the Topinello. [I think that both surviving arches can be seen from the other side of the bridge, which is in the grounds of the Liceo Scientifico].

-

✴The third arch in the drawing above no longer survives, but its original existence is suggested by the symmetry of the arrangement .

The Pons Cipiscorum (Ponte di Cippischi) here was documented in two wills of a lady called donna Bonafemina, in 1275 and in 1277. This is another of four bridges across the Topinell that is the subject of a scholarly debate as to its possible Roman origins (as discussed in my page Roman Walk III).

Continue along Via Isolabella, which follows the line of the branch of the Topinello. Continue to the junction with Via San Giovanni dell’ Acqua, the site of the Ponte di San Claudio, discussed above.

Turn right along Via San Giovanni dell’ Acqua,

to continue with the main part of the walk.

Continue to Piazza XX Settembre, on the left. This is the site of three important Patrician Palaces:

-

✴Palazzo Monaldi Barnabò is on the left:

-

✴Palazzo Jacobilli Carrara is on the right; and

-

✴Palazzo Gherardi is at the far side of the piazza.

Turn left at the end into Via Scuola dei Arti e Mestieri:

-

✴the Piazza San Nicolò and church of San Nicolò are immediately on the right; and

-

✴the ex-church of San Tommaso dei Cipischi is farther along, again on the right.

Continue to the junction with Via Antonio Gramsci.

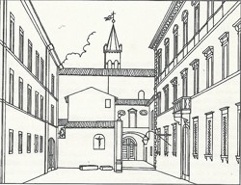

From Vladimiro Cruciani (1998, below) Figure 8

Turn right along Via Gramsci and continue t0 Palazzo Brunetti Candiotti (at number 2-4, on the right. My photograph, on the right, shows this palace on the right. The arch to the left of it leads to the side door of San Domenico and, on the right, to the Oratorio del Crocifisso: thy campanile of San Domenico is visible behind it; both of these are visited later in the walk.

Fabio Pontano, in his ‘Discourse’ (1618), which has been edited by Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 2008), recorded (at pp. 42-3) that:

-

“Inside the city, near the church of San Domenico, there is an ancient arch, which I think served as a gate of the city before its expansion ... ” (my translation).

For Ludovico Jacobilli (1646), as reported by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 317, entry 107), the arch had been incorporated in the city walls of the 12th-13th centuries as a gate known as porta de Petitu:

-

✴Giovanni Francesco Pivati (referenced below, 1747, at p. 377, search on ‘Scafali’) described it as an ancient arch under the house of the noble Scafali family.

-

✴According to Vladimiro Cruciani (referenced below, 1998, at p. 29:

-

“... in front of the side door of [the church of] San Domenico, there was a [city] gate with an arch and large Roman blocks ...” (my translation).

This arch (in its medieval form) was destroyed (along with the Scafali palace) to make way for Palazzo Brunetti Candiotti (1781).

In the diagram, Vladimiro Cruciani (as above) relied on a 19th century drawing in the Biblioteca Comunale di Foligno. (The building with a crucifix on its wall, which stands to the left of this arch in the drawing, no longer exists). Although the porta de Petitu had been demolished some decades before the date of the drawing, a pilaster and two large blocks that had probably belonged to the medieval gate remained on the site. [Two blocks in the courtyard of Palazzo Candiotti might have belonged to it]:

-

✴According to Fabio Pontana, Roman remains were incorporated into this gate (as discussed in my page Roman Walk II).

-

✴As discussed in the page on city gates (which deals, inter alia, with porta de Petitu), the reconstituted arch almost certainly stood here in 1087, when the church now known as Santa Maria Infraportas (visited later in the walk) was designated as “foris portam”.

Return along Via Gramsci to the junction with Via Scuola dei Arti e Mestieri: all of the buildings in the block on the left beyond this point constituted the Insula dei Vitelleschi in the 14th century. The properties were subsequently split into four Patrician Palaces:

-

✴three that have their main entrances in Via Antonio Gramsci:

-

•Palazzo Vallati Montogli (at the corner of Via Antonio Gramsci and Via Palestro);

-

•Palazzo Piermarini Prosperi Valenti (number 48); and

-

•Palazzo Vitelleschi (number 52-4); and

-

✴while Palazzo Gigli [Rutilli?] has its entrance at number 1 Via Palestro.

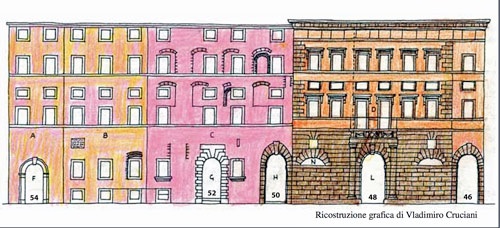

Reconstruction by Vladimiro Cruciani (Archeofoligno, 2006)

The reconstruction above shows the present arrangement of first two of these palaces. Despite its grand appearance, the main entrance at number 48 leads only to the garden of Palazzo Piermarini Prosperi Valenti: the main entrance to this palace is at number 50, to the left (which actually projects into Palazzo Vitelleschi).

The part of the complex between the portals at numbers 48 and 50 was originally a tower. If the door at number 50 is open, you can see that the left side of this tower (i.e. the wall on your right) incorporated a stretch of walls some 7 meters long by about 2 meters high made of travertine blocks that were probably cut in the Roman period (as discussed in my page Roman Walk II).

Continue to the building at number 67-9 on the right, which stands at the junction with Via Saffi: it is known alternatively as Palazzo Benedetti, Palazzo Rossi or Palazzo Bocci, the name that I use here. Michele Faloci Pulignani (referenced below, 1907, at p. 16) referred to this building as a factory of the 14th century, a possibility suggested by the two arches in the side wall in Via Saffi (see the photograph on the left). Fabio Bettoni and Bruno Martinelli (referenced below, at p. 149), who referred to the building as the “residenza dei Benedetti”, pointed to the arms of Cardinal Tiberio Crispi on the corner here (see the photograph on the right): since Crispi was the papal legate of Perugia in 1545-8, they suggested that:

-

“... perhaps an old commercial property here was converted into a small palace in the 16th century” (my translation).

They further suggested that the facade of the building was moved at that time into to Via Gramsci. (The same change of facade seems to have occurred at Palazzo Vallati (16th century) opposite (see the photograph on the right): its design was apparently changed during construction, so that its facade was moved from Via Palestro to Via Gramsci). We might therefore reasonably assume that the Roman fragments were incorporated into the new facade at 67-9 Via Gramsci in the middle of the 16th century.

The new facade of Palazzo Bocci incorporates a small number of Roman fragments (discussed in my page Roman Walk II).

Front 0f the tower, at 20 Via Gramsci Side of the tower, in Via Quattrocento

Walk back along Via Gramsci, passing Palazzo Alleori-Ubaldi at number 53 on the left.

Return to Palazzi Bocci (above), where the detour ends.

You are now at the junction of Via Palestro (on your right) and Via Aurelio Saffi. If you look along the former, you will notice that this is a straight street as far as you can see. In fact, it follows this line all the way to the Ponte di San Giovanni d’Acqua (above). Turn left along Via Aurelio Saffi, which still follows this line: as discussed further below, this might have been the cardo maximus of Roman Fulginia.

-

✴The college extended to the left as far as Via della Misericordia , and incorporated the church of San Pietro in Pusterna, which the Barnabites purchased in 1614.

-

✴The entrance to the college, at number 18, has a damaged fresco of St Peter above it.

Take a short detour by turning left along Via della Misericordia:

-

✴The entrance at number 18 on the left belongs to the church of San Pietro in Pusterna. This church was first documented in 1213, and the frescoes on the right wall are the oldest to survive in Foligno. It later became part of the complex of San Carlo (above).

-

✴The Oratorio della Misericordia is further along on the left, opposite number 11.

It is possible to visit both of these monuments on request to the Istituto di San Carlo, which has its office at 18 Via Saffi (on the right in the vestibule).

Return to Via Aurelio Saffi and continue to the junction with Via Mazzini and (ahead) Via Cairoli. Take a short detour by turning left along it:

-

✴Palazzo Cibo Nocchi is at number 60.

-

✴A plaque commemorating Michele Faloci Pulignani can be seen in the wall between numbers 50 and 48.

The medieval house at number 49 has the remains of a fresco in a double aedicule in its facade. It depicts the Annunciation, (although only the left part of the angel survives) with the standing St Peter on the left.

Retrace your steps along Via Mazzini to the junction with Via Saffi (right) and Via Cairoli (left). As discussed in my page Roman Walk II, some scholars think that this was the centre of the Roman city.

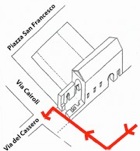

It is now time to think again about the early medieval city walls. The name of the ancient church of San Pietro in Pusterna (which is now to your right) suggests that there was a small city gate (pusterla) nearby, which scholars suggest - reference needed - was in an early stretch of wall along what is now Via Mazzini . The city seems subsequently to have expanded along Via Cairoli, so that a new wall parallel to this one was built in ca. 1240 beyond Piazza San Francesco (as we shall soon see).

Take a short detour by continuing along what becomes Via Antonio Rutile and left along Via Cesare Agostini. The Arco dei Polinori ahead bears the Trinci and Beccafumi arms. It connects Casa dei Beccafumi (15th century) at number 5 on the left to the house opposite, which has fragments of similar architecture under the modern plaster. Presumably these two houses once belonged to the Trinci family.

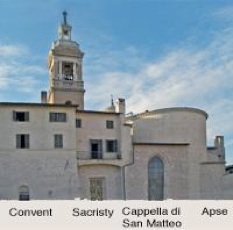

Turn right along Via Luigi Fratini, which runs behind the church and convent of San Francesco. Look through the gate of the convent to see (from right to left):

-

✴the present semi-circular apse of San Francesco;

-

✴the back wall of the original square apse, with a large window;

-

✴the back wall of the Cappella di San Matteo [which contains Roman remains ??]; and

-

✴the back wall of the sacristy, which contains the remains of Porta San Matteo, discussed below.

The city wall mentioned above was probably built in ca. 1240, when Foligno became the centre of a Ghibelline confederation. It was demolished after the Guelf victory of 1253. It probably ran from the tower in Via del Campanile (above), on a line parallel to Via Luigi Fratini (i.e. on your right) as far as Via Benedetto Cairoli (ahead). This wall seems to have enclosed the Palazzo Imperiale (below), which was later incorporated into the friars’ convent. It included two gates:

-

✴Porta San Matteo, remains of which survive in the wall of the sacristy of San Francesco, as mentioned above); and

-

✴Porta Abbatis, which was probably in Via Benedetto Cairoli. This gate was documented in 1241, but no trace of it now survives.

Santa Maria Infraportas (to the left) Ex-convent and church of San Domenico

Continue into Piazza San Domenico, with:

-

✴the church of Santa Maria Infraportas to the left; and

-

✴the ex-convent of San Domenico and church of San Domenico (below) ahead. (The ex-convent housed the Collegio Sgariglia, a school run by the Somaschi Fathers, in the period 1928-71).

-

✴In 1207 , the church was documented as "Sancte Marie extra portam vel in porta’" (Santa Maria outside or at Porta de Petitu (see below).

-

✴It presumably became known as Santa Maria Infraportas (between the gates) after the construction of Porta Santa Maria.

Continue the detour by walking along Via Mazzini, to the right of Casa degli Atti. Palazzo Gentili-Spinola is at number 125 on the right.

On leaving San Domenico, turn left to continue along Largo Frezzi: the Oratorio del Crocifisso is immediately on the left, at the junction with Via Antonio Gramsci. (it has recently become open at weekends). Turn left on leaving the Oratorio del Crocifisso, along Via Gramsci. Walk into the courtyard of Palazzo Brunetti Candiotti and to the left to see its campanile.

Return to Via Gramsci. As discussed above, there seems to have been a city gate, Porta de Petitu, across the street here that survived into the 17th century. It must have belonged to an interim circuit of walls that pre-dated the construction of the walls containing Porta Santa Maria (above) in ca. 1240.

Continue along Via Gramsci into Piazza della Repubblica, where the walk ends.

Read more;

G. Galli (Ed.), “Foligno, Città Romana: Ricerche Storico, Urbanistico e Topografiche sull' Antica Città di Fulginia”, (2015) Foligno:

G. Galli, “Foligno Città Romana: Considerazioni sugli Studi Topografici e sulle Emergenze Archeologiche”, pp. 35-74

P. Camerieri, “Il Castrum e la Pertica di Fulginia in Destra Tinia”, pp. 75-108

P. Guerrini and F. Latini, “Foligno: Dal Municipium Romano alla Civitas Medievale: Archeologia e Storia di una Città Umbra”, (2012) Spoleto

L. Lametti, “Il Palazzo: Dalle Preesistenze all'Unita d'ltalia”, in

G. Benazzi and F. Mancini (Eds), “Il Palazzo Trinci di Foligno”, (2001) Perugia, pp. 51-104

V. Cruciani, “Mura e Città: Il Caso di Foligno nel Trecento”, (1998) Foligno

K. Schubring, “Foligno e le Sue Mura Civiche dal Duecento fino ai Nostri Giorni”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno", 17 (1993) 7-18

Return to the home page on Walks in Foligno.