The museum is laid out in nine rooms in Palazzo Trinci:

-

✴the Sala Gotica on the first floor and five rooms beyond it, which I have labelled Rooms 1-5;

-

✴Rooms 6 and 7 on the mezzanine, reached from the stairs down from Room 4; and

-

✴in three rooms (8-10) on the ground floor, at the foot of the Gothic staircase.

The description below of the exhibits in each room relates to the situation in 2016.

Leave the ticket office by the arch ahead, to the left. As you emerge, the Gothic staircase is on your left: descend it for rooms 8-10. For the other rooms, continue ahead into the (signed) Sala Gotica.

Sala Gotica

Piazza del Risorgimento during excavations

(Photograph in Sala Gotica)

This lovely room contains a description of excavations carried out in 1998 in Piazza del Risorgimento, in the area of Santa Maria in Campis (which is visited in Roman Walk I). These excavations uncovered a stretch of Roman road that crossed the piazza diagonally, directed towards what some scholars believe were the sites of the Roman theatre and amphitheatre near Villa Sassonia (i.e. from lower right to upper left in the illustrations above).

This road seems to have been in use from at least the 3rd century BC.

-

✴2o tombs were excavated along the north side of the road, which dated to the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD. Another tomb and a funerary tower were found to slightly to the north.

-

✴Two small votive bronze (ca. 500 BC), which are exhibited in Room 6, were also found during the excavations. They presumably came from an ancient sanctuary, which had probably been associated with the Umbrian necropolis in nearby Via Po.

These excavations are described in the book by Maria Laura Manca and Samuele Ranucci referenced below.

Coin Hoards

The exhibits in this room relate to:

-

✴a hoard of Roman coins that was found at the junction of Via Vitelli and Via Trasimeno in 1962; and

-

✴a second hoard found during the excavations in Piazza del Risorgimento in 1998.

These locations (both visited Roman Walk I) are marked in the plan above (displayed in the Sala Gotica), and both hoards are described by Samuele Ranucci (referenced below, 2012). (For more detail, see his paper of 2007, also referenced below).

C0in Hoard found in 1962

This hoard of Roman silver coins was discovered at the junction of Via Vitelli and Via Trasimeno (1) in 1962. 156 coins survive, and these might well represent the totality of the original hoard. These are exhibited with a fragment of a ceramic container that suggests the now-lost original in which they were buried. These coins covered a time span from the 3rd to the 1st century BC. The most recent of these coins (RRC 511/3a) was minted in Sicily by Sextus Pompeius and dated to 42-40 BC, which suggests that the hoard was buried during the war, and that the unfortunate owner was never able to recover them.

C0in Hoard found in 1998

A second hoard of over 3,000 silver coins that had been buried in a leather sack was found in 1998 during these excavations of Piazza del Risorgimento (2). The museum exhibits a selection of the restored coins and a photograph of them as they were found in 1998 (reproduced here). These coins also covered a time span from the 3rd to the 1st century BC.

RRC 523/1a: C·CAESAR·III·VIR·R·P·C/ Q·SALVIVS·IMP·COS·DESIG

The most recent of the coins in the hoard (RRC 523/1a) had been minted in the name of Octavian and his general, Quintus Salvidienus Rufus, who was identified as consul-designate. In fact, Salvidienus had been nominates as one of the consuls for 39 BC but he was subsequently accused of treachery against Octavian and died (either by suicide or execution) before he could take up his office. The coins issued in his name therefore date to 40 BC. Since he had played a central role in the siege of Perusia in 41-40 BC, Samuele Ranucci [c] (referenced below, at p. 89) observed that:

-

“It seems probable that the coins had been minted by the besiegers of Perusia for the [payment of the] legions engaged in the war effort ...” (my translation).

The museum commentary indicates that the value of these coins in 40 BC would have been been somewhat in excess of the amount that a single legionary would have earned during his career.

Foligno had, in fact, been caught up in the war in early 40 BC when Octavian’s generals, Agrippa and Salvidienus, had confined an army here that had mustered in order to attempt to raise the siege. Samuele Ranucci [c] (referenced below, at p. 87) suggested that the hiding of this hoard and the one from site 15 (below) was probably directly related to these events. Samuele Ranucci [b] (referenced below, at p. 26) pointed out that there is no secure basis on which to determine what the precise reasons for the hiding of the coins might have been:

-

“One can, of course, speculate, imagining, for example, that we are dealing with the savings of a high-ranking officer or the valuable loot of a thief, rather than the treasury of an army, buried in a hurry. Alternatively, as is probably preferable, we could leave the explanation to the imagination of each individual” (my translation).

We can also only speculate on the reason why the unfortunate owner of the coins never recovered them.

Room 1

This room is devoted to the results of successive excavations of an Umbro-Roman sanctuary at Cancelli di Foligno, some (some 13 km east of Foligno and 9 km south of Pale, the site of another ancient sanctuary - see Room 6 below). As Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below, 2009) explained, its existence has been known since the late 19th century, when votive offerings were found in the cemetery here. The remains of successive phases of the sanctuary itself, beginning in the Republican period, were discovered in 2012-3. There is also evidence of a nearby Umbria village.

Votive offerings from Cancelli (6th – 3rd century BC)

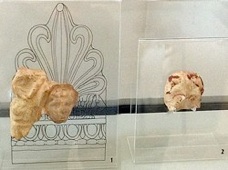

Terracotta Antefixes

The museum exhibits fragments of two of the antefixes that would have decorated the sanctuary:

-

✴(1): from the late 1st century BC or the early 1st century AD; and

-

✴(2): from the Republican period.

Room 2

Necropolis at Santa Maria in Campis

This room contains a description of the excavation of the necropolis at Santa Maria in Campis (which is visited in Roman Walk I) and displays grave goods from the site. Evidence for a Roman necropolis here first emerged in 1948. Further find were made in 1970, when work on the extension of the civic cemetery was underway. This led to a programme of systematic excavation in 1970-8 that unearthed some 180 tombs (1st - 3rd centuries AD). The era of heaviest use of the necropolis was in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. The necropolis clearly extended along a stretch of Via Flaminia that was also unearthed during the excavations. The detailed results were described by Margherita Bergamini (referenced below).

Grave goods from tombs 33

This group of tombs seem to have belonged to a single family. Grave goods include two coins:

-

✴one from tomb 33b, which dated to the reign of Lucius Verus (161-9 AD); and

-

✴one from 33f, the tomb of a baby, which dated to the reign of Trajan (98-117 AD).

Grave Goods from tomb 160

Take the steps up to Room 3, which used to be the ticket office.

Room 3

Lions (13th century)

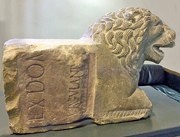

These two stone statues of lions here came from the portal of the (now demolished) church of church of Santa Maria Maddalena. They were carved from stone that bears a Roman inscription (CIL XI 7997, 1st century AD):

-

✴] EX DON[...] / [...] URGULANIU[s(?)], on the left side of the lion exhibited on the right; and

-

✴]R Iun[, on the right side of the lion exhibited on the left.

Turn right into Room 4.

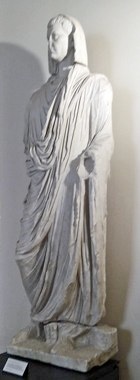

Room 4

Figure in a toga (1st century AD)

Room 5

Inscriptions from Fulginia

Inscriptions of the Curvii (late 1st century AD) [7 and 8]

CIL XI 5210 CIL XI 5211

These two inscriptions (translated by Hugo Whitfield, referenced below, at pp. 45-6) are on the bases of statues decreed by the decurians to their city’s “best patrons”, the brothers:

-

✴Cnaeus Domitius Afer Titus Curvius Lucanus di Nemausus (Nîmes), (CIL XI 5210, which was in the collection of Eusebio l’Eremita in the early 16th century); and

-

✴Cnaeus Domitius Curvius Tullus (CIL XI 5211), which was in the Palazzo del Governatore Apostolico (Palazzo Trinci) in the early 17th century and subsequently passed to the collection of Ludovico Jacobilli).

Although they were the sons of Sextus Curvius, they were adopted during their father’s lifetime by the wealthy rhetorician Domitius Afer. Pliny the Younger, in his letter to Rufinus, described how Domitius Afer (who died in 59 AD) had bequeathed his considerable wealth to his adoptive sons. He also gossiped about how Domitius Tullus had adopted Domitia Lucilla, the daughter of Domitius Lucanus, in order to get his hands on his dead brother’s legacy, but had then made a handsome bequest to her on his own death in 108 AD. She had thus became extremely eligible, and ended up as the grandmother of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius. The inscriptions, which the EDR database (see the CIL links) date to the last two decades of the 1st century AD, largely describe the brothers’ illustrious military careers. It seems likely that they came from Fulginia and that the brothers had had a residence here.

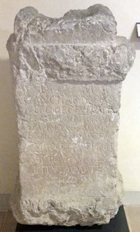

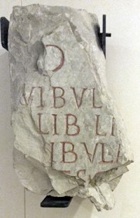

Funerary Inscription (1st century BC) [31]

-

“... in 1836 , in a field belonging to signor Nocchi [?] in vocabolo Cocchi, near the Villa di Fiamenga” (my translation from CIL).

Enrico Zuddas and Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, at p. 62), following Ferdinando Castagnoli, suggested that Fiamenga was at:

-

“... the point of convergence between the territories of Spello, Bevagna and Foligno” (my translation).

The inscription, which is now exhibited in the Museo Archeologico (Room 5), reads:

Cn(aeus) Decimius Cn(aei) f(ilius) Lem(onia) Bibulus

evocatus leg(ionis) XIII / VIvir

The deceased was thus Cnaeus Decimius Bibulus, who had been an evocatus (a soldier who had served out his time and obtained a discharge but had voluntarily enlisted again) in l. His assignation to the Lemonia (the tribe of Hispellum) indicates that he had been settled there after his second retirement. He had also been a Sevir (member of a magustracy of six men), presumably at Hispellum.

Thus it is not clear whether the land on which Bibulus had been buried had previously belonged to Mevania or to Fulginia (Foligno). However, they pointed out that a later inscription (CIL XI 5033) from Fiamenga commemorated a magistrate from Mevania, which suggests that this city is the more likely candidate.

In fact, there is epigraphic evidence for another veteran from legio XIII who was apparently settled at Hispellum (as evidenced by his tribal assignation): a second funerary inscription (CIL XI 1933, 30-1 BC from località Agliano, south of Perugia, which is now in the deposit of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Perugia, commemorates Caius Allius, a centurion of this legion. The colony at Hispellum had been formed in 41 BC, after the Battle of Philippi. However, Lawrence Keppie (referenced below, at p. 179) recorded that, while legio XIII had fought with Julius Caesar in Gaul , it had been disbanded before Philippi. The legion had been reestablished by 36 BC, when (according to Appian, ‘Civil Wars’, 5:87) it saved Octavian’s life after a disastrous battle in his war against Sextus Pompeius. According to Keppie, men serving in the re-formed legion would not have been discharged before Actium (31 BC).

-

✴Lawrence Keppie (referenced below, at p. 179) suggested that:

-

“Allius and Bibulus could be Caesarian evocati [re-recruited before Philippi] (though their legion was not apparently re-formed under that numeral), but the evidence is too slight to form any conclusion”.

-

If this was the case, they could have been settled at Hispellum at the time of its original deduction.

-

✴However, Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 436) suggested that the more likely scenario was that both men had fought in the reformed legio XIII and were part of a second wave of veteran settlement at Hispellum after Actium.

Sisani is surely correct: after all, there is nothing to suggest that Allius was an evocatus. The likely scenario is that both men fought with legio XIII at Actium and that they were subsequently resettled at Hispellum. If this was the case, then Gabba’s suggestion that land here had been confiscated following the Perusine War is incorrect: after Actium, land for veteran settlement in Italy was acquired by purchase, rather than by confiscation. The land on which Bibulus was buried might have been in a corridor of land that was purchased at that point to link Hispellum to Via Flaminia.

Donation of CIL XI 5223 by Carlo and Francesco Elisei (1672)

-

“... a great sensation when it was discovered because a lively debate was underway at that time on the antiquity of the city of Foligno and its Roman origins, which were denied by some scholars” (my translation).

The donors, who carefully listed the classical authors who had referred to the Roman city, now gave the world proof of its location. Unfortunately, as discussed below in the context of the inscription itself, no precise record of the find spot survives.

Finds from Forum Flaminii

The small town of San Giovanni Profiamma, some 6 km north of Foligno, stands on the site of the Roman settlement of Forum Flaminii, a trading post that developed in ca. 220 BC at the northern junction of the two branches of Via Flaminia (see the page "Around Foligno"). The following objects came from a large complex of Roman baths that was discovered here in the 19th century and excavated more fully in the early 20th century.

Head of Livia (14-31 AD) [1]

-

“In 1911, excavations on the right edge of [Via Flaminia, as one travels towards the Adriatic] ... brought to light the remains of a fountain in concrete, faced with bricks and small rectangular blocks of stone”.

These excavations also uncovered this bust of Livia, which was apparently part of the fountain (the precise location of which is no longer known).

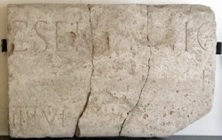

Inscription (1st century AD) [2]

[CES]IAE C(AI) [FILIAE]

[S]ABINAE

[PA]RENTI MUNIC[IPII]

DEC(URIONUM) [DECRETO]

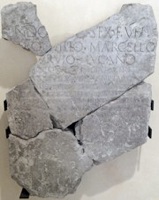

Inscriptions (ca. 200 AD) [7 and 8]

CIL XI 5215 CIL XI 5216

These inscriptions (CIL XI 5215-6) are on the base of a statue that was found at San Giovanni Profiamma. It had been erected by the “splendidissimus ordo Foroflaminiensium” and commemorate Publius Aelius Marcellus, a member of the Papiria tribe. Since he is also commemorated in an inscriptions from the Roman province of Apulum (in modern Romania), which belonged to this tribe, it seems certain that this had been his place of birth. He served with distinction in three legions, including the II Gemina Pia Felix, which was given this title in ca. 197 AD. It was probably thereafter that he embarked on a civic career: as decurion and patron of his native Apulum; and also as patron of the cities of Forum Flaminii, Fulginia and Iguvium (Gubbio). [What was his link to Umbria ??]. The EAGLE database (see the CIL link) dates the inscriptions to the period 193-235 AD.

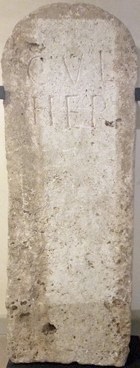

Funerary Inscription of Cnaeus Pompullius Hister [6]

This inscription (CIL XI 5246) [Date ??] from San Giovanni Profiamma reads:

CN(aei) POMPULLI T(iti) f(ilii) / COR(nelia) HISTRI

Inscriptions from Hispellum (Spello)

Inscription (27 BC - 14 AD) [11]

-

“In the convent of the Madonna del Vico [of Spello], there is a small square stone that was found in 1615, not far from that church [now known as the Chiesa Tonda, some 700 meters north of the Roman sanctuary at Villa Fidelia]” (my translation).

It is clear from Donnola’s transcription that he referred to CIL XI 5263:

[Ser]venius |(mulieris) l(ibertus) Chilo

aedem Minerv(ae) opere

[tec]t(orio) camera(m) limi[na]

[l]api(de) rub(ro) asseres

...m cludend(am)

f(acienda) cur(avit)

The inscription, which also found its way into the collection of Ludovico Jacobilli, records a temple of Minerva that was restored in local ‘pietra rossa’ (pink stone) by Servenius Chilo, the freedman of a lady. It is discussed more fully in the page on the Roman sanctuary at Spello.

Funerary Inscriptions from Hispellum [32 and 33]

CIL XI 5348 CIL XI 5303

These inscriptions, both of which date to the 1st century AD, commemorate (respectively):

-

✴Veturia Rufa (CIL X 5348), from the Augustan period; and

-

✴Luciius Castricius (CIL XI 5303), from to period 30 - 1 BC).

Return to Room 4 and take the steps on the right down to Room 6.

Room 6

Inscriptions from Fulginia and its Territory

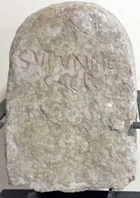

Inscription (ca. 200 BC) [1]

SUPUNNE

SACR

It is not clear whether the language is Umbrian or Latin, but it is likely that the cippus marked the boundary of an area that was sacred to an otherwise unknown goddess, Supunna. Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below, 2014, at p. 134) reproduced the early records of this inscription and the two main hypotheses relating to the identity of Supunna:

-

✴Alberto Calderini (referenced below, at p. 63) revived the traditional hypothesis that she was a river goddess (since ‘Supunna’ might associated with the ‘Tupino’, the Topino river of Foligno); this would be similar to the case of Clitumnus, a god associated with the nearby river of that name).

-

✴Paolo Vitelozzi (referenced below) referred to the hypothesis that the etymology suggested an old Latin verb “to throw”, which might indicate that Supanna was a goddess who presided over the preparation of food in the course of rituals of sacrifice.

This inscription is also described in the page on Umbrian Inscriptions after 295BC.

Inscription from San Pietro di Flamignano (ca. 200 BC) [2]

Detail

According to Chiara Lorenzini (referenced below, at p. 32), this inscription (EDR 162789) was:

-

“... found in 1928 in a field at Colle S. Pietro, between Trevi and Sant’ Eraclio, in the locality of San Pietro in Flamignano, along [the eastern branch of] Via Flaminia, about 2 km from a fountain known locally as ‘Petruio’” (my translation).

The text, which is in the Umbrian language and uses the Latin alphabet, reads:

bia . opset

marone

t . foltonio

se . ptrnio

The first line relates to the construction of something described as a ‘bia’ (probably a fountain) while the final two lines record the names of two marones (magistrates, whose office is still denominated in the Umbrian language): T(itus) Foltonius; and Se(xtus) Petronius. This suggests that these ‘marones’ had commissioned the ‘bia’, although it is alternatively possible that their names were recorded merely as a dating device, following Roman practice. Given the find spot of the inscription, we might reasonably assume that Titus Foltonius and Sextus Petronius were marones of Fulginia.

According to Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, pp. 381-2):

-

“[On the basis of paleographic analysis,] it is difficult to countenance a date later than [ca. 200 BC]: a “terminus circa quem” (approximate date) is furnished by the opening of Via Flaminia [in 220 BC], with which the building project mentioned in the inscription could have been connected” (my translation).

The fact that the inscription uses the Latin alphabet is consistent with this hypothesis, since the Via Flaminia would have been instrumental in the Romanisation of the territory through which it ran. However, the retention of the Umbrian words for the chief magistracy suggests that the inscription was not much later than the opening of the road.

This inscription is also described in the page on Umbrian Inscriptions after 295BC.

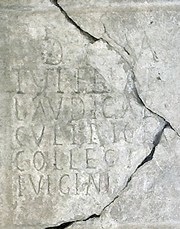

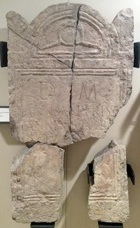

Funerary Inscription (ca. 200 AD) [3]

Detail

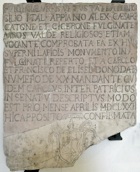

An inscription in Room 5 (above) records that Carlo and Francesco Elisei donated this inscription (CIL XI 5223) to the people of Foligno in 1672. It reads:

D(is) M(anibus)/ Tutiliae/ Laudicae

cultrices/ collegi(i)/ Fulginiae

Thus, in this funerary inscription, the ‘cultrices’ (worshippers) of the college of Fulginia commemorated Tutilia Laudica, who had presumably been among their members before her death. It is not clear whether “Fulginia” referred to the Roman city or alternatively to a divinity for whom it had been named. Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below, 2014, at p. 136) commented that the Roman inscription caused:

-

“... a great sensation when it was discovered, because a lively debate was underway at that time on the antiquity of the city of Foligno and its Roman origins, which were denied by some scholars” (my translation).

The 17th century inscription recording its donation recorded only that it had been found “in agro Fulginate”. However, Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below, 2014, at p. 136) reproduced information provided in 1725 by its first editor, Giustiniano Pagliarini, according to which it had been found accidentally in 1671 on land owned by Marchesi Elisei that was less than a mile from Foligno. Unfortunately, the precise location of the find spot cannot be securely identified:

-

✴According to Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below, 2014, at p. 138):

-

“At the moment, it is impossible to locate topographically the land owned by the Elisei on which the inscription was found: properties of the family seem to be attested only in the areas of Pale and the Altolina, locations that cannot be described [as less than a mile from Foligno]. Nothing however prevents the hypothesis that the inscription had actually been purchased by the Elisei [brothers] ...” (my translation).

-

✴However, Fabio Bettoni and Bruno Marinelli (referenced below, at p. 62) asserted that the Elisei family owned the palace now at 14 Via XX Settembre, between Via del Oratorio and Via Elisei. This location (actually in the city) clearly does not meet Giustiniano Pagliarini’s description, but I wonder whether he was correct?? It is interesting to note that the garden of this palace might well have included at least part of the “agellus” (cemetery) in which St Felician was thought to have been buried, and in which Tutilia Laudica could also conceivably have been interred.

Altar of Romulus (ca. 309 AD) [5]

DEO ROMULO

The museum note suggests that is was associated with divus Romulus, the divinised young son of the Emperor Maxentius, who had died in 309 AD.

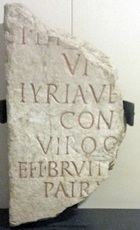

Titus Haterius Nepos (2nd century AD) [7-9]

CIL XI 5212 CIL XI 5213 CIL XI 5214

This room contains three inscriptions that commemorated Titus Haterius Nepos, all of which probably came from Fulginia:

-

✴CIL XI 5213 commemorated a Prefect of Egypt. Although the first line, which would have identified him, is missing, he is usually identified as a Titus Haterius Nepos, who held the post in 120-4 AD. Catherine Ross (referenced below, at p. 136) translated the inscription as follows:

-

[To Haterius], prefect of the cohort, military tribune, prefect of the Anavionensian Britons, procurator of Augustus for Armenia Major, of the Great Training-School, and of legacies; and in charge of the census, in charge of petitions of Augustus, prefect of the Watch, prefect of Egypt, M Taminius Ce...

-

According to Antony Birley (referenced below, 1997, at pp. 100-1), who assumed that Fulginia was Haterius Nepos’ home town, this inscription also covered a hectic period of his career under the Emperor Hadrian in ca. 114-9 AD, prior to his appointment to Egypt.

-

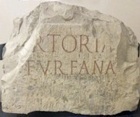

✴CIL XI 5214, which was apparently from the crypt of the Duomo, describes essentially the same career:

censi]tor[i Brittonum ...] / [ proc(uratori) ludi ma]gni her[editatium ...]

[... praef(ecto) vigil]um prae[fe(cto) Aegypti] / ... [p]atri [

-

According to Antony Birley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 307), this inscription, which seems to have been erected by a son or daughter, might well have been funerary in nature.

-

✴CIL XI 5212, which apparently came from land owned by the Jacobilli family near Santa Maris in Campis, reads:

T(ito) Haterio Nepoti / Atinati Probo/ Publicio Mateniano

co(n)s(uli) pontif(ici) triumphalib(us)/ [ornamentis honorato

-

This inscription commemorates the magnificently-named Titus Haterius Nepos Atinas Probus Publicius Matenianus, the suffect Consul of 134 AD. According to Antony Birley (referenced below, 2007, at p. 308), he was probably a son of the Haterius Nepos above, and his triumph probably related to his role in suppressing the second Jewish revolt (132-6 AD).

Slabs from the Forum (?) (late 1st century BC) [12]

The museum displays four fragments of paving slabs, each of which shows evidence of part of an inscription:

-

✴one fragment from an unspecified location that had been inscribed L(ucius) V[....]; and

-

✴three fragments of a single slab from Villa La Quiete in Colpernaco (some 5 km east of Foligno), which recorded an unknown quattuorvir quinquenalis, [...] IIII VIR QUIN[....].

[I wonder if Lucius V.... might be Lucius Varenus, who was recorded in CIL XI 5220a (early 1st century AD) as a quattuorvir iure dicundo ??]

According to Bernardino Lattanzi (referenced below, at p. 86), who cited the “Cronache di Foligno” of Ludovico Jacobilli, the slabs from Villa La Quiete had been:

-

“... among the oldest used in an early medieval tomb [there ... and were of a type] that was usually used in the pavements of Roman fora ...”

Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1984, at pp. 478-9), who referred to the recent discovery of the tomb at Villa La Quiete, was of the same opinion: he observed that the slabs:

-

“... were incised with letters that would have been picked out in bronze, which were usually characteristic of the paving of fora. [The inscription in this case] mentioned a quattuorvir quinquennalis. This therefore confirms that [Fulginia] had a notable vitality in the early imperial period, when it was [apparently] urbanised” (my translation)

Funerary Inscription (2nd century AD) [17]

Funerary Altar (2nd century AD) [20]

C(aio) Anchario C(ai) f(ilio) Cor(nelia)/ Vero

dec(urioni) Fulg(iniae)

aed(ili) / F(oro)f(laminiensium)

The altar was subsequently used to hold holy water in the church of San Giovanni Decollato, which was demolished in 1869.

This inscription contains two important pieces of information:

-

✴Ancharius’ assignation to the Cornelia tribe, rather than the Oufentina of Forum Flaminii, suggests that he came from Fulginia, which must therefore have been assigned to the Cornelia.

-

✴Fulginia and Forum Flaminii still had separate administrations, albeit that a man from Fulginia could serve in the administration of Forum Flaminii.

Funerary Altar (1- 120 AD) [21]

[---]ius Ẹutych[es]

[---? Pr]imae liberta

[--- qu]artus vicensimus annus

[--- fl]ebilis hic titulus

Boundary Marker (date ??) [22]

CULTORES HERCULIS

It probably marked the boundary of a cemetery used by a confraternity of cultores (worshippers) of Hercules.

Funerary Altar (1st century AD) [23]

Inscriptions from San Valentino di Civitavecchia

Base of Statue to Semo Sancus (1st century AD) [4]

Inscription (1st century AD) [11]

This inscription (CIL XI 5225) from San Valentino di Civitavecchia commemorates a quattuorvir iure dicundo, probably named Caius Septulmius.

Funerary Inscription (date ??) [27]

Inscriptions from Forum Flaminii

Funerary Inscription (date ??) [34]

Funerary Inscription (1st half of 1st century AD) [35]

Funerary Inscription (ca. 1st century AD) [37]

Display Case 1

This display case in the middle of Room 6 contains grave goods from unspecified tombs from the necropolis of Santa Maria in Campis and from the more recent excavations in nearby Piazza del Risorgimento.

Finds from Piazza del Risorgimento (3rd and 2nd centuries BC)

These fragments of black-glazed pottery were discovered in Piazza del Risorgimento (see Roman Walk I) in 1998 in the canal that ran along the north side of a Roman road that ran diagonally across the piazza..

Display Case 2

Grave goods (6th – 5th centuries BC)

These grave goods came from two of the six tombs that were discovered in 1976 in Via Po (see Roman Walk I). This is almost the only evidence of the pre-Roman Fulginates near the modern city, and the site may have marked to edge of the lake that was later drained for the Roman municipium.

Display Case 3

This display case, at right angles to Case 2, contains remains from the Umbrian sanctuaries:

-

✴on Sasso di Pale;

-

✴at Plestia; and

-

✴in Via Po (see also above).

Antefixes from Sasso di Pale (3rd century BC)

These terracotta antefixes came from a sanctuary on an artificial terrace at the summit of the Sasso di Pale (see the page "Hike: Belfiore - Foligno"). The sanctuary had been in use in pre-Roman times, but was monumentalised in the early Roman period.

Finds from Sasso di Pale

Votive Objects from Plestia (6th - 5th centuries BC)

Antefixes from Plestia (3rd century BC)

Votive Objects, probably from Via Po (ca. 500 BC)

Walk though the arch at the end of the room, into Room 7.

Room 7

The funerary objects in this room came from the necropolis at Santa Maria in Campis (see Roman Walk I).

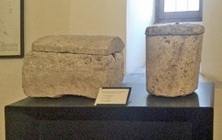

Urns (ca. 1st century AD)

These two urns were discovered in 1949.

Sarcophagus (1st century BC)

Reconstructed inhumation grave (2nd century AD)

Return to the Gothic staircase and walk down it to Rooms 8-10.

Room 8

Mosaic (6th or 7th century AD)

Rooms 9 and 10

Mosaic floors (2nd century AD)

These mosaics came from rooms in a Roman domus that was discovered slightly to the east of Piazza del Risorgimento (see Roman Walk I) in 1968. The mosaic in black and white tesserae illustrated above is a detail of a larger composition.

Objects in Other Museums

Hercules of Foligno (probably early 1st century AD)

-

“ ... a long trial between M. Guardabassi, a rich landowner of Perugia, and M. Bonichi, the Roman dealer, who had lost his case. The cause of dispute was this: Bonichi, taking an archaeological tour, stopped at Foligno, and saw, somewhere in the outskirts of the town, a beautiful bronze leg in the hands of a peasant ... [who told him] that the rest of the statuette had also been dug up, but was appropriated by a friend living [nearby. ... He bas away but] his wife at once produced the torso of the Hercules when asked for it, which only needed the leg belonging to the other peasant, as well as the other foot and lower part of the leg, to be quite perfect.”

Bonichi took the leg back to Rome, but he was unable subsequently to buy the torso because Guardabassi had beaten him to it, which led to his unsuccessful legal action. Tyskiewicz was then able to buy the leg and to tempt Guardabassi to exchange the torso for another important artefact. He the recorded:

-

“I was able to have it put together by [the Roman dealer] Martinetti, who fixed the right leg on to the body and reconstructed the lower part of the left and the foot ( both missing since the discovery of the bronze) placing the whole on an antique base. I then took it to Paris, and it was included among the collection that I sold to Napoleon III [who donated it to the Musée du Louvre, Paris in 1870].”

However, that was not the end of the story:

-

“Some time after, being on my way to Egypt, I stopped for the night at Foligno ... [where] I happened to see in the shop window of a tobacconist and wine merchant the foot and part of the leg of my Hercules, which Martinetti had been forced to re-cast in bronze. I bought the precious fragment and sent it to the Louvre, where it may now be seen beside the statue, for it was not thought advisable to meddle with the modern foot. But what is still more curious is that, in the year 1894, Martinetti told me that he had in his possession the club of Hercules, which had been found not long before in the same place as the statuette, and I have the pleasure of announcing, before I finish my account of this interesting discovery, that this fourth fragment, which has been most kindly presented to me by the son of Martinetti, has rejoined its three companions, collected by so strange a series of accidents, in the Louvre”.

In fact, according to the museum notes, the club is not the original one from Foligno. They also state that:

-

“Believed by some to be nearly contemporary with the sculpture by Lysippos, this statuette may date from the beginning of the Roman Empire (first century AD).”

Bernardino Lattanzi (referenced below , at p. 103) suggested that it might have been associated with a small statue of Hebe (the wife of Hercules) which was found in 1811 during the excavations of what was probably a private thermal complex from the early imperial period near Santa Maria in Campis, which was adjacent to the domus described above (see Roman Walk I).

Read more:

G. Galli (Ed.), “Foligno, Città Romana: Ricerche Storico, Urbanistico e Topografiche sull' Antica Città di Fulginia”, (2015) Foligno

G. Galli, “Foligno Città Romana: Considerazioni sugli Studi Topografici e sulle Emergenze Archeologiche”, pp. 35-74

P. Camerieri, “Il Castrum e la Pertica di Fulginia in Destra Tinia”, pp. 75-108

M. Romana Picuti, “Tra Epigrafia e Antiquaria: le Iscrizioni di Supunna e delle Cultrices Collegi Fulginiae nel De Diis topicis Fulginatium di Giacomo Biancani Tazzi”, in:

E. Laureti (Ed.), “G. Biancani: De Diis Topicis Fulginatium Epistola, Foligno 1761”, (2014 ) Spello, pp. 129-43

E. Calandra, “Mosaico: Forum Flaminii”, in”

A. Bravi (Ed.), “Aurea Umbria: Una Regione dell’ Impero nell’ Era di Costantino”, Bollettino per i Beni Culturali dell’ Umbria, (2012) p. 84

M. L. Manca and S. Ranucci (Eds.), “I Tessoretti Romani di Foligno”, (2012) Perugia

M. L. Manca, “Foligno Archeologica”, pp. 7-10

S. Ranucci, “Tessoretto Rinvenuto nel 1962”, pp. 11-16

M. Romana Picuti, M. Albanesi and S. Ranucci, “Tessoretto Rinvenuto nel 1998”, pp. 17-26

S. Sisani, “I Rapporti tra Mevania e Hispellum nel Quadro del Paesaggio Sacro della Valle Umbra”,, in

G. Della Fina (Ed.), “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, (2012) Orvieto (pp. 409-64)

H. Whitfield, “The Rise of Nemausus from Augustus to Antoninus Pius: A Prosopographical Study of Nemausian Senators and Equestrians”, (2012) Thesis, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

P. Vitellozzi, in:

L. Agostiniani et al. (Eds), “Screhto Est: Lingua e Scrittura degli Antichi Umbri”, (2011) Città di Castello, entry 38 (p. 56)

E. Zuddas and M. Spadoni, “La Lemonia nella Valle Umbra”, in

M. Silvestrini, “Le Tribù Romane: Atti della XVIe Rencontre sur l' Épigraphie (Bari 8-10 ottobre 2009)”, (2010) Bari, pp 57-64

C. Ross, “'Tribal Territories' from the Humber to the Tyne: an Analysis of Artefactual and Settlement Patterning in the Late Iron Age and Early Roman Periods”, (2009), thesis from the University of Durham

M. Romana Picuti, “Ricerche Vecchie e Nuove sul Territorio di Cancelli di Foligno (PG) in Epoca Romana”, in

M. Cancelli (Ed.),” Cancelli, l’Arte del Gregge”, (2009) Milan, pp. 8-19

L. Sensi (Ed.), “Discorso di Fabio Pontano sopra l’ Antichità della Città di Foligno”, (2008)

A. Birley, “Two Types of Administration Attested by the Vindolanda Tablets”, in

R. Haensch and J. Heinrichs (Eds), “Herrschen und Verwalten: Der Alltag der römischen Administration in der Hohen Kaiserzeit”, (2007) Cologne.

S. Ranucci, “Un Ripostiglio di Monete Romane Repubblicane da Foligno”, Annali dell’Istituto Italiano di Numismatica, 53 (2007), pp. 115-53

S. Sisani, “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

A. Calderini, “Iscrizione Umbre”, in”

M. Matteini Chiari (Ed.), “Raccolte Comunali di Assisi: Materiali Archeologici; Iscrizioni; Sculture; Pitture; Elementi Architettonici”, (2005) Perugia, pp. 51-78

F. Bettoni and B. Marinelli, “Foligno, Itinerari Fuori e Dentro le Mura”, (2001), Foligno

C. Lorenzini, “Iscrizione dei Marones da San Pietro in Flamignano”, in:

“Fulginates e Plestini: Popolazioni Antiche nel Territorio di Foligno: Mostra Archeologica”, (1999) Foligno

A. Birley, “Hadrian: The Restless Emperor”, (1997) Abingdon

B. Lattanzi, “Storia di Foligno: Dalle Origini al 1305”, (1994) Foligno

M. Bergamini (Ed.), “Foligno: La Necropoli Romana di Santa Maria in Campis”, (1988) Perugia

L. Sensi, “Fulginia: Appunti di Topografia Storica”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 8 (1984) 463-92

V. Cruciani and L. Sensi, “Rinvenimenti Archeologici a Piazza Grande”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 6 (1982) 9-16

E. Gabba, “Trasformazioni Politiche e Socio-Economiche dell' Umbria dopo il 'Bellum Perusinum'”, in:

G. Catanzaro and F. Santucci (Eds), “Bimillenario della Morte di Properzio”, (1986) Assisi pp. 95-104

D. Manconi, “Un Cippo Funerario Romano dalla Piazza Grande di Foligno”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 8 (1984) 501-2

L. Keppie, “Colonisation and Veteran Settlement in Italy (47-14 BC)”, (1983) London

T. Ashby and R. A. L. Fell, “The Via Flaminia”, Journal of Roman Studies, 11 (1921) 125-90

Return to Palazzo Trinci.

Return to the page on Museums of Foligno.

Return to Roman Walk II.