Location of Roman Fulginia

Michele Faloci Pulignani (in a publication of 1936, quoted by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini, referenced below, at p. 75, note 291) observed that:

-

“The land on which our city of Foligno was built is virgin land and, however extensively it is excavated, ... important remains of ancient buildings ... are never brought to light. In contrast, every time one moves the earth near the church of Santa Maria in Campis, one finds ancient objects of all kinds ...” (my translation).

Thus, he believed that Roman Fulginia had been located, not on the “virgin soil” of medieval and modern Foligno, but in what is now the suburban area around Santa Maria in Campis, a kilometre from the modern city, on the eastern branch of Via Flaminia. I explore the surviving evidence for this hypothesis in my page Roman Walk I.

Although this view was challenged in the 1930s by Giovanni Dominici (referenced below), it is probably fair to say that it remains the ‘received wisdom’. However, Giuliana Galli and Paolo Camerieri (in separate articles in the books referenced below of 2015 and 2016) have recently refined Dominici’s alternative hypothesis - that Roman Fulginia was on the site of the modern city.

-

✴In this page (Roman Walk II), I suggest a walk around this putative Roman city to look at the surviving evidence within its boundaries; and

-

✴in Roman Walk III, I explore the potentially complementary evidence that relates to the four bridges beyond its northwestern boundary that once spanned the Tinia/ Topino river in its original course.

I attempt to evaluate the results of all three explorations in my page on the Location of Roman Fulginia.

Street Plan of Foligno

Plan of the Roman Castrum proposed by Paolo Camerieri,

superimposed on an aerial view of the modern city

Adapted from P. Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, p. 94, Figure 1)

For Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, at p. 75):

-

“Foligno [is] ... a city of Roman foundation: ... a glance at the street plan of the city or, better still, at an aerial photograph, is sufficient to arouse in any scholar of ancient urban topography the well-founded suspicion that this assumption is more than likely to be correct ...” (my translation).

He deduced (at p. 81) that:

-

✴the decumanus maximus of this city ran along what are now Via Mazzini and Via Garibaldi; and

-

✴the cardo maximus ran along what are now Via San Giovanni dell’ Acqua, Via Palestro, Via Saffi and Via Cairoli.

Camerieri further argued (at p. 81) that there is evidence for a second cardo, running along what are now Piazza della Repubblica, Largo Carducci and Corso Cavour, suggesting the layout of a typical Roman castrum (fortified army camp), as illustrated at his Figure 15:

-

✴the first cardo would have been known as the Via Principalis (although the term cardo maximus is used here); and

-

✴the second cardo would have been known as the Via Quintana (5th street).

Giovanni Dominici (referenced below, at p. 39) had already reached broadly the same conclusions, except that he had reversed the identification of these last two streets.

New proposal for the assignation of the centuriated land to the west of modern Foligno

Adapted from Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, 2015, p. 106, Figure 14)

Paolo Camerieri also related the street plan of modern Foligno to the centuriation of the land immediately to the west of it (marked “pertica of Fulginia (?)” in the plan above). As he explained (at p. 77, note 111):

-

“[Fulginia] was not identified [as a possible owner of this land in earlier research, in which] the whole plain between Bevagna and the Via Centrale Umbra [marked CM/ VQ in the plan above] was assigned to [Mevania] in an uncritical way. [This was because] Fulginia was in fact then placed by most local scholars at Santa Maria in Campis, on the [eastern branch of] Via Flaminia, and its territory was assumed to lie entirely on the hydrographic left of the Topino” (my translation).

However, as he explained at p. 92, on the basis of the new model he proposed for the location of Fulginia, the junction of its decumanus maximus and cardo maximus is almost a textbook example of an angulus clusaris (closing angle) of a centuriated area. He noted (at pp. 92-3) that:

-

“... it was previously unrecognised that the true geometric-topographical reference point of the pertica on the hydrographic right of the Topino is the centre of modern Foligno rather than Bevagna. [In fact], there are serious problems with the relationship between Bevagna and this centuriated area, given the lack of isotropy [shared orientation] between them and also the absence of a clear, direct and non-artificial modular relation between .. the city and [its putative] territory” (my attempted translation of what is a very technical passage).

In other words, this territory had more probably belonged to Fulginia, which was now (in his view) correctly located at modern Foligno.

Finally, Camerieri pointed out that the lack of any correspondence between the orientation of the centuriation of this land and the branch of Via Flaminia that crosses it suggested that the land had been divided before the consular road was built (i.e before 220 BC).

Walk around the Putative Roman City

For those scholars who doubt that modern Foligno had Roman origins, its orthogonal street plan alone provides insufficient proof. Thus Laura Bonomi Ponzi (referenced below, at p. 12):

-

“First of all, the regularity of an urban plan is inconclusive proof of Roman origins if it is not supported by concrete archeological evidence” (my translation).

The first part of the walk therefore explores the street plan above and the surviving evidence along the way.

The walk begins and ends in Piazza della Repubblica, outside the minor facade of the Duomo (at the left in this photograph), inside the putative Roman city and close to its most northerly point. In the headings below, indications like (A-B) refer to the street plan above. Locations in bold italics also feature in Walk II (which explores the non-Roman sites in this part of the city).

Northwest Boundary of the Putative Roman City (A-B-C)

Palazzetto del Podestà Entrance to Via Gramsi,

with Palazzo Trinci on the right

In the present context, the area around Piazza della Repubblica is the most complicated part of the puzzle, and I will discuss the possible Roman remains hear when we return later in the walk.

Leave the piazza along Via Gramsci, with Palazzo Trinci on your right. This follows most of the northwest boundary of the putative Roman city (although, as you will see, this boundary also extended for a little way behind you). Note the Roman block embedded at the righthand corner of Palazzetto del Podestà, where Via Gramsci leaves the piazza (labelled in the photograph on the right, just above the level of the pavement).

18 and 20 Via Gramsci

20 Via Gramsci Side wall in Via Quattrocentro

Continue to the medieval tower at number 20 on the right, which forms part of to Palazzo Nuti Deli. This tower stands on a base of travertine blocks that were probably cut in the Roman period (visible in the first few courses above ground level in Via Gramsci and in Via Quattrocento, which runs along the right side of the tower).

For Laura Bonomi Ponzi (referenced below, at p. 12):

-

“The numerous squared blocks that have been reused:

-

✴in [the left wall of the house at] 18 Via Gramsci; and

-

✴in the medieval towers in the same street [which include that next to Palazzo Nuti Deli discussed here and that in Palazzo Piermarini Prosperi Valenti, discussed below];

-

in part belonged to a Roman funerary monument that was sited in this street ” (my translation).

Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below) similarly asserted that:

-

✴“The numerous squared blocks have been reused in the construction [of the house at 18 Via Gramsci] probably came from a nearby Roman funerary monument” (my translation from p. 315, in entry 102); and

-

✴“The medieval tower [at number 20], which is adjacent to Palazzo Nuti Deli, probably dates to the 13th century, ....: the base however is made up of reused squared travertine blocks that probably came from a nearby Roman monument of some kind” (my translation from at p. 315, in entry 103).

None of these authors presented their evidence for the assertion that at least some of these blocks came from one or more funerary monuments.

However, for Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2015, at p. 49):

-

“In Foligno, square travertine blocks are seen reused in buildings at different locations in Via Gramsci, at Palazzo Deli [and] in Via Colomba Antonietti [see below]: [they represent] a ‘concentration of pre-existence’ that corresponds to the area that was related to the [putative Roman] castrum” (my translation).

In a later paper (referenced below, 2016, at p. 115) she observed that:

-

“The dating ... has been attributed to the early 3rd century BC, clearly subject to revision on the basis of studies in progress” (my translation).

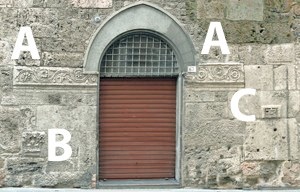

Palazzo Bocci

The facade of Palazzo Bocci (at number 67-9 Via Gramsci, on the left), which stands at the junction with Via Saffi (the putative cardo maximus) incorporates interesting Roman fragments: as discussed in Walk II, they were probably incorporated into this facade in the middle of the 16th century. They comprise:

-

✴a decorative frieze (A-A);

-

✴a corinthian capital from a pilaster (B); and

-

✴a block with the representation of a wicker cist (C, also illustrated to the right), which has been inserted upside down.

There is a wide variation in views as to the origins of these Roman fragments:

-

✴For one group of scholars, the frieze and capital were typical of funerary monuments “a dado” (see this Augustan example from Modena), an architectural group discussed by Mario Torelli (referenced below, at p. 159 et seq.).

-

•Wilhelm Von Sydow (referenced below) described a particular tomb that belonged to this group: the mausoleum (late 1st century BC) of the gens Socellia at Pietrabbondante. He listed seven other examples (at p.289), one of which had been the source of the fragments above in the facade of Palazzo Bocci.

-

•Laura Bonomi Ponzi (referenced below, at p. 13), followed by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, pp. 275-6, in entry 29) also suggested that the fragments probably came from a Roman funerary monument.

-

✴However, for the following scholars, these fragments came from a Roman arch:

-

•Michele Faloci Pulignani (referenced below, 1907, p. 16 and photograph at p. 18);

-

•Giovanni Dominici (referenced below, at p. 27, and photographs at p. 18 and p. 19);

-

•Bernardini Lattanzi (referenced below, at pp. 93-5), who followed Luigi Crema (below); and

-

•Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2015, at pp. 51-3), who deemed them to be:

-

“... typical of the Augustan period ... and apparently from an arch or a city gate” (my translation from p. 51).

As I discuss in my page on the Location of Roman Fulginia, I think that the presence of fragment C, which probably has funerary connotations, militates in favour of the first possibility.

Cardo Maximus (B-B1-B)

Via Saffi, from Via Gramsci Junction of Via Saffi/ Via Mazzini/ Via Cairoli

Take a short detour by turning left along Via Aurelio Saffi, the cardo maximus of the putative Roman city. Continue to the junction with:

-

✴Via Mazzini (the putative decumanus maximus, to the right and left); and

-

✴Via Cairoli (the continuation of the putative cardo maximus).

If this was indeed the site of Roman Fulginia, then we have arrived at its forum.

There is epigraphic evidence that suggests the existence of a forum at Fulginia: according to Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1984, at pp. 478-9), , shortly before the time at which he was writing, some Roman paving slabs had been discovered at Villa La Quiete in Colpernaco (some 5 km east of Foligno), where they had been re-used in an early medieval tomb. He observed that:

-

“... they were incised with letters that would have been picked out in bronze, which were usually characteristic of the paving of fora. [The inscription in this case] mentioned a quattuorvir quinquennalis (a municipal magistrate). This therefore confirms that [Fulginia] had a notable vitality in the early imperial period, when it was [apparently] urbanised” (my translation)

In fact, the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci displays:

-

✴a slab from an unspecified location (illustrated on the left, above), which is inscribed L(ucius) V[....]; and

-

✴three fragments of a long slab from the Villa La Quiete, which recorded an unknown quattuorvir quinquenalis, [...] IIII VIR QUIN[....].

However, there is no evidence for the original location of these stones.

The blue-painted facade ahead on the right, at number 8 Via Cairoli, belongs to Palazzo Casalini (16th century). According to Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, p. 278, in entry 35), two tombs covered by tiles were found in 1889 in front of this palace (close to the point marked B in the photograph above), just a meter below the level of the road . The grave goods included some small phials made of coloured glass, two iron nails and other fragments.

-

✴Guerrini and Latini dated these burials to the Roman period, which would suggest that this location was not inside Roman Fulginia.

-

✴However, Paolo Camerieri and Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2016, at p. 18, note 24) argued that these burials were more probably evidence of:

-

“... the presence in Foligno of the medieval practice of burial... within abandoned buildings. ... [These tombs], which were found under the pavement of the current road, would have been realised inside [residential] insulae, since the ancient road did not coincide with the present road but instead ran under the buildings a monte [on which side ?]” (my translation).

I discuss this important difference of view as part of my overall assessment of the evidence for the putative Roman city in the page on the Location of Roman Fulginia.

Retrace your steps to Via Gramsci and turn left along it.

Palazzo Piermarini Prosperi Valenti

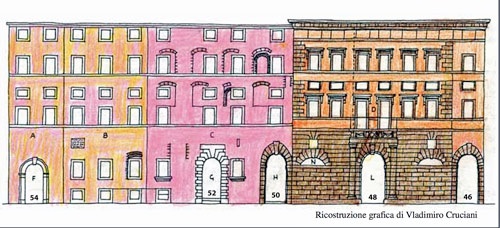

Reconstruction by Vladimiro Cruciani (Archeofoligno, 2006)

The palaces illustrated above at 46-54 Via Gramsci are now known as:

-

✴Palazzo Piermarini Prosperi Valenti (number 46-8); and

-

✴Palazzo Vitelleschi (number 50-4).

While the entrance at number 48 looks like the main entrance to Palazzo Piermarini Prosperi Valenti: it leads only to the garden: the main entrance to this palace is at number 50 (which actually projects into Palazzo Vitelleschi).

The part of the complex between the portals at numbers 48 and 50 was originally a tower. If the door at number 50 is open, you can see that the left side of this tower (i.e. the wall on your right) incorporated a stretch of walls some 7 meters long by about 2 meters high, made of travertine blocks that were probably cut in the Roman period. Again, we have a difference of view among scholars as to their significance:

-

✴Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, pp. 314-55, in entry 101), quoted Laura Bonomi Ponzi but without a specific reference:

-

“For Bonomi Ponzi, this very small ambient suggests its use as a tower, probably in the medieval period, so it seems likely that the ancient blocks have been reutilised for its base” (my translation).

-

✴Matelda Albanesi (in Guerrini and Latini, referenced below, Appendix 2, pp. 362-3) also believed that these Roman blocks had been reused in what she considered to be a medieval building.

-

✴However, according to Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2015, at pp. 47-50), this stretch of ancient wall remains in situ (i.e. it stands on Roman foundations):

-

“It is built in opus quadratum in squared blocks, prepared with accurately worked contact surfaces and quite precise joints. The orientation NW-SE is compatible with the orthogonal structure of the walls of a tower on the northern limit of the [putative Roman] castrum” (my translation).

-

She dated the wall to the 3rd century BC, and related it to the walls of Lucca, which were probably built at the time that a Roman colony was established there in 180 BC (see Lily Ross Taylor, referenced below, for this date). Giuliana Galli returned to this site in a later paper (referenced below, 2016, at pp. 113-4), suggesting that:

-

“There is [also] a direct correspondence with some tracts of the Roman city walls at Terni (the prefecture of Interamna Nahars)... the surviving circuit of walls [there] is in opera quadrata of ... local travertine ... The proposed dating is around the 3rd century BC” (my translation).

This difference of view is important: as noted above, Laura Bonomi Ponzi (referenced below, at p. 12) warned that:

-

“... the regularity of an urban plan is inconclusive proof of Roman origins if it is not supported by concrete archeological evidence” (my translation).

In other words, while Roman blocks incorporated into medieval buildings located within an orthogonal street plan might be suggestive, conclusive proof of Roman origins requires evidence for Roman walls or buildings in such locations. I discuss this further in my page on the Location of Roman Fulginia.

Porta de Petitu

End of Via Gramsci in the 19th century End of Via Gramsci now

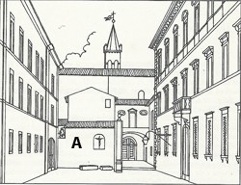

From Vladimiro Cruciani (1998, p. 30, Figure 8) Building A in the plan no longer survives

Fabio Pontano, in his ‘Discourse’ (1618), which has been edited by Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 2008), recorded (at pp. 42-3) that:

-

“Inside the city, near the church of San Domenico, there is an ancient arch, which I think served as a gate of the city before its expansion ... ” (my translation).

For Ludovico Jacobilli (1646), as reported by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 317, entry 107), the arch had been incorporated in the city walls of the 12th-13th centuries as a gate known as porta de Petitu:

-

✴Giovanni Francesco Pivati (referenced below, 1747, at p. 377, search on ‘Scafali’) described it as an ancient arch under the house of the noble Scafali family.

-

✴According to Vladimiro Cruciani (referenced below, 1998, at p. 29:

-

“... in front of the side door of [the church of] San Domenico, there was a [city] gate with an arch and large Roman blocks ...” (my translation).

This arch (in its medieval form), which stood at the end of Via Gramsci, was destroyed (along with the Scafali palace) to make way for Palazzo Brunetti Candiotti (1781), the large palace to the right in both the plan and the photograph above.

In the plan, Vladimiro Cruciani (as above) relied on a 19th century drawing in the Biblioteca Comunale di Foligno. It is compared above with a modern photograph of the same location:

-

✴The side door of San Domenico, is under the arch to the right, and the campanile of the church can be seen behind it.

-

✴Building A, which stands to the left of this arch in the plan, no longer exists.

Although the porta de Petitu had been demolished some decades before the date of the drawing, a pilaster and two large blocks that had probably belonged to it remained on the site. [Two blocks in the courtyard of Palazzo Candiotti might have belonged to it ??].

Fortunately, both Fabio Pontano and Ludovico Jacobilli recorded aspects of the appearance of the porta de Petitu before its demolition:

-

✴Fabio Pontano (as above) noted that it:

-

“... was truly made in the shape of an arch and, next to it, there are two large pieces of ancient columns that I believe formed part of it. This arch is made in the Doric style, similar to the Arch of Titus in Rome, although it is certain that [the structure in Foligno] did not serve the same purpose as such arches in Rome, which honoured important people. It is made of stones that are of great antiquity, but these have been taken from earlier structures, particularly from funerary structures. This [funerary provenance] is evident from the left side of the arch, where a standing man faces the church: on one of the large stones here, one can read [a Roman funerary inscription] ... This is a clear sign that this stone, together with others here, have been taken from other structures and, in particular, from a number of ancient funerary monuments” (my translation).

-

✴Luigi Sensi kindly sent me the following account of this arch by Ludovico Jacobilli (Bibl. Com. ms. F. 198, p. 40), which largely follows that of Pontano:

-

“Inside Foligno, near the side door of the church of San Domenico, under the house of the Scafali, [there is] an ancient Doric arch, similar to the Arch of Titus in Rome, [which is made] of stones that have great antiquity, which have been reused from the oldest edifices and, in particular, from a number of funerary monuments; because, in one of these stones, you [can still read] some letters [from a funerary inscription]” (my translation).

-

✴Ludovico Jacobilli (as above) recorded that the structure:

-

“... incorporated worked Roman stones and a stone sculpture of Pan” (my translation).

Jacobilli’s figure of Pan presumably corresponds to Pontano’s standing man facing San Domenico.

Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p, 317, entry 107) reasonably observed that it is:

-

“... difficult to hypothesis a date and an interpretation for this [medieval arch], in the absence of material evidence and only on the basis of descriptions from the 16th/17th centuries” (my translation).

Although these early accounts stress the funerary provenance of some of the Roman elements reused in the medieval gate, other components of it could have come from a Roman arch, as discussed further my page on the Location of Roman Fulginia.

Southwest Boundary of the Putative Roman City (C-D)

Piazza San Domenico, outside the walls of the putative Roman city

Santa Maria Infraportas (on the left) looks across the piazza towards the line of the putative city wall

Turn left along Largo Frezzi, which runs along the right side of San Domenico (the church on the right in the photograph above, which is now an auditorium). You are now just outside the putative Roman city, with its southwest boundary on your left. Continue ahead across Piazza San Domenico (with the lovely church of Santa Maria Infraportas across the piazza to your right).

Stop for a moment at the junction with Via Mazzini on your left: as noted above, this road, which is parallel to Via Gramsci, follows the line of the decumanus maximus of the putative Roman city. (As far as I know, there is no archeological evidence to support this assumption, which is made purely on the basis of topography).

Continue ahead along Via Cortella, to the junction with Via Madonna del Giglio. So far, you have been following the southwestern boundary quite closely, but you will now have to divert slightly from it: turn right along Via Madonna del Giglio and left along Via Santa Caterina to the junction with Via del Cassero. This junction is slightly to the south of the southern most point of the putative Roman city.

Southeast Boundary of the Putative Roman City (D-E-F)

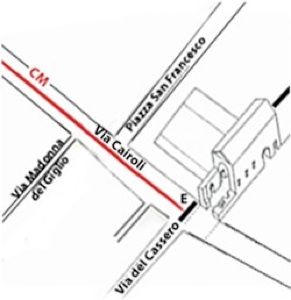

Street plan of part of the putative Roman city superimposed on

a reconstruction of the so-called Palazzo Imperiale, from Vladimiro Cruciani (1990)

Turn left along Via del Cassero, to begin your walk along the southeast border of the putative Roman city. Continue to Via Cairoli (the putative cardo maximus). In the plan above, Vladimiro Cruciani has reconstructed the so-called Palazzo Imperiale (ca. 1240), which once stood at or near this junction. This important Ghibelline monument was soon incorporated into a part of the Convento di San Francesco. However, according to Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (at pp. 315-6, entry 101), the remains of the entrance portico of the imperial palace were still visible from Via Cairoli in the 19th century.

According to Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2015, p. 55):

-

“... some surviving stretches of walls from the later Roman period are probably embedded in the medieval walls of Foligno, awaiting recognition: [this might be the case] in the so-called Palazzo Imperiale ...” (my translation).

She suggested (at pp. 55-6) that a stretch of wall along the southeast wall of what is now the convent of San Francesco, which was unearthed in 1999, seemed to date to the late Roman or early medieval period, with the possibility that an older layer of wall survives below it. (Her reference to the local tradition that St Felician was imprisoned on this site in 250 AD can be discounted: BHL 2846 (search on ‘2846’ in this link) specifically says that he was imprisoned at Forum Flaminii before being sent to Rome, and he died during the journey outside civitas Fulginia.)

Putative Via Quintana (F-A)

Turn left along Corso Cavour, part of the Via Quintana of the putative Roman city, to the junction with Via Mazzini (the putative decumanus maximus). Continue along Largo Carducci (still following the Via Quintana, as illustrated above on the right). The steps ahead, to the left of the main facade of the Duomo, lead to the Museo Diocesano in the Palazzo dei Canonici (the over-restored building to the left).

According to Paolo Camerieri and Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2016, p. 29, Figure 3), Via Quintana originally continued ahead, between the Palazzo dei Canonici and the left wall of the Duomo, cutting through what is now the left transept of the latter. You will have to divert around the obstruction to enter Piazza della Repubblica, and continue to the minor facade of the Duomo, where this walk began.

Piazza della Repubblica

Roman Temple In Piazza della Repubblica (?)

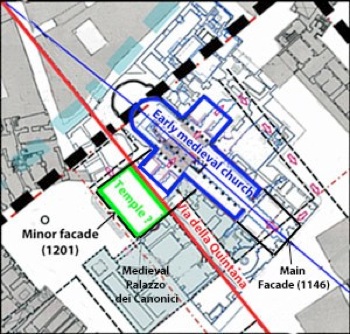

Via della Quintana and the axis of the Duomo

Present facades of the Duomo labelled in black

Adapted from Camerieri and Galli (2016, p. 51, Figure 11)

As mentioned above, according to Paolo Camerieri and Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2016, p. 29, Figure 3), the putative Via Quintana of the Roman castrum was interrupted by the later building of the Duomo and the adjacent Palazzo dei Canonici. However, Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2016, at p. 90) suggested that it is possible to identify the earlier situation, in which the first Duomo here had been built to the side of this road, with its axis slightly inclined to it. On this model, the green rectangle in the plan above represents an earlier, probably Roman, building that had been perfectly aligned with the road.

Giuliana Galli suggested that the green rectangle might have been the site of a Roman temple on a podium of 12 x 22 meters. On the model developed at various points in this book, the structure underwent two subsequent changes of use:

-

✴it was first converted into a church in the paleochristian period; and

-

✴in 1201, it was incorporated into the left transept of the Duomo, the facade of which is still perfectly aligned with the line of the putative Via Quintana).

The following Roman remains discussed below might have been related to this temple:

-

✴remains of a Roman cornice in the minor facade;

-

✴fragments of Roman columns:

-

•in the courtyard of Palazzo Trinci; and

-

•in the crypt of the Duomo; and

-

✴a fragmentary inscription that commemorates Juno and Minerva, which is now embedded in one of the columns of the crypt,

Remains of a Roman Cornice in the Minor Facade of the Duomo

According to Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1994, at p. 83):

-

“ ... two elements of Roman cornices were inverted to serve as the bases of the arches [of the portal of the minor facade of the Duomo]” (my translation).

The corresponding entry 37 in the catalogue of Guerrini and Latini reproduces this information (although it erroneously places them on the main facade). Giuliana Galli (as above) suggested (at pp. 90-1) that these white marble fragments had originally been:

-

“...elements of the cornice of the trabeation of a temple” (my translation).

Given their present location, it is at least possible that they were found in 1201, at the time that the site of the putative temple was incorporated into the present left transept.

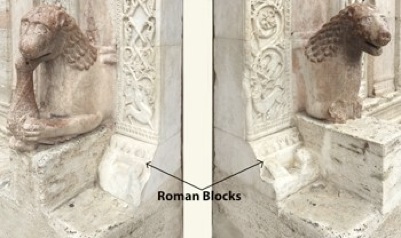

Roman remains in the Loggia of the Minor Facade of the Duomo

According to Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1994, at pp. 83-4), a number of Roman fragments were incorporated into the the loggia in the minor facade:

-

✴The capitals (four Corinthian and the fifth Composite) of the five arches at the front of this loggia:

-

“... were certainly reused, and came from the decoration of a relatively small edifice of the middle Imperial period” (my translation).

-

He cited (at note 6) an earlier source that dated the capitals to ca. 300 AD. The corresponding entry 39 in the catalogue of Guerrini and Latini followed this dating.

-

✴The architrave between the middle column in the rear of and the pilaster behind it was formed from a reused piece of marble:

-

“We are dealing with a fragment of a Roman statue, with the remains of a left leg, with drapery” ” (my translation).

-

The architrave, which is not visible from the exterior, is illustrated as his Figure 72.

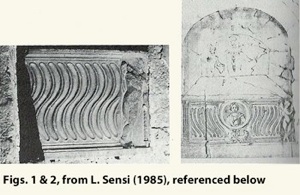

So-called Sarcophagus of St Messalina in the Duomo

Walk into the Duomo and turn right to the the Cappella della Madonna di Loreto (the 1st chapel on the left, at the base of the campanile, immediately before the crossing). Unfortunately, the door of this chapel is usually closed, which is a shame because it still contains part of a Roman sarcophagus that is known as the sarcophagus of St Messalina, a young woman who was mentioned in the legend of St Felician (BHL 2846). According to the legend, the pagan authorities recognised her as a Christian when she visited St Felician in prison, and she was consequently clubbed to death.

Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1985, at pp. 310-11) suggested that the sarcophagus had probably been inserted here during the rebuilding of part of the Duomo in 1133 (which culminated in its reconsecration in 1146 to SS Felician, John the Baptist and Florentius), which:

“... constituted the occasion on which to collect the relics of saints venerated by the local church, among which were probably those of St Florentius. Changes of cult and structural changes to the interior of the church [subsequently] left these ancient relics and their [original chapel] in oblivion” (my translation).

The main events in this pattern of evolution:

-

✴the “discovery” of the relics in the sarcophagus in 1599 and their formal recognition as those of St Messalini in 1613.

-

✴the construction of the new Cappella della Madonna di Loreto here, albeit that the sarcophagus remained at least partially visible thereafter; and

-

✴structural work in the 18th century that involved angular pilasters of of the cupola.

Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1985) illustrated (as above):

-

✴the remaining fragment of the sarcophagus in situ as his Figure 1; and

-

✴a sketch of the whole sarcophagus in this location (his Figure 2): this sketch had been included in the documentation of the process of 1613 that led to the formal recognition of the relics in the sarcophagus as those of St Messalina.

The sides of the sarcophagus were strigillated (covered with carved fluting that resembles the curved Roman grooming tool known as a strigil). There was a representation of the head of a lady at the centre, a standing putto at the extreme right and a pilaster at the extreme left. Luigi Sensi deduced from the asymmetry of this arrangement that it had been recomposed from two Roman sarcophagi, which he dated to the 2nd century AD.

Once again, there is no surviving evidence for the original location of the associated graves. Since the sarcophagi were re-used on this site close to the northwestern boundary of the putative Roman city, they could have come from a nearby but extra-urban cemetery.

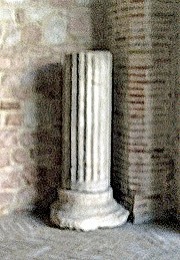

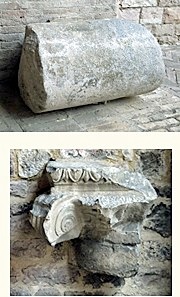

Remains of Roman Columns in Palazzo Trinci

Return to the piazza using the exit in the left transept and continue around it in the anti-clockwise direction and walk through the iron gate of Palazzo Trinci to see its main courtyard. These Roman remains against the back wall comprise:

-

✴a fragment of a fluted column;

-

✴two fragments of columns in white/black granite;

-

✴a fragment of a granite Ionic capital.

Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2016, at p. 98 and Figure 56) suggested that these fragments (and others that are now in the crypt of the Duomo, discussed below) came from the putative temple on the later site of the left transept of the Duomo that was discussed above.

According to Giuliana Galli (as above), these remains:

-

“... probably came from an excavation carried out under the Duomo, since the fluted travertine column here has the same diameter as a fragment in the Duomo [found during recent excavations, according to note 251, and now] embedded in the wall of the crypt” (my translation).

She further suggested that:

-

“The two [fragments of] columns in white/black granite [here] seem to be the two cited by [the engineer Antonio] Rutili Gentile [in his notes of the ‘excavations’ under the Duomo of 1824]” (my translation).

While both points are suggestive, it is important to remember that archeological finds from a wide area around Foligno were exhibited in the courtyard of Palazzo Trinci in the 19th century.

Via Pertichetti

(As far as I am aware, no other scholars have considered the possible Roman provenance of these blocks.)

Via Colomba Antonietti

Via Colomba Antonietti is the street that runs under the open archway in the façade of Palazzo Comunale, parallel to Via Pertichetti (above). Matelda Albanesi (in Guerrini and Latini, referenced below, Appendix 2, pp. 362-3 and Figure 94) observed that the large blocks incorporated into the wall immediately on the right here are:

-

“... considered by some to be proof of the existence of Roman buildings in [this] area ... ” (my translation).

However, she added that recent excavations:

-

“... have confirmed that the blocks were clearly reused, following the practice employed in other medieval buildings (including the towers of Palazzo Deli and the entrance to Palazzo Piermarini [discussed above]), which were intended to confer prestige as well as structural stability. [In the case of Via Colomba Antonietti, the Roman blocks] in fact rest on medieval foundations made up of small limestone blocks of varying sizes, and also include a fragment of a sandstone frieze from an arch” (my translation).

For Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2015, at p. 49):

-

“In Foligno, square travertine blocks are seen reused in buildings at different locations ... [in Via Gramsci and] in Via Colomba Antonietti: [they represent] a ‘concentration of pre-existence’ that corresponds to the area that was related to the [putative Roman] castrum” (my translation).

In a later paper (referenced below, 2016, at p. 115) she observed that:

-

“The dating ... has been attributed to the early 3rd century BC, clearly subject to revision on the basis of studies in progress” (my translation).

Funerary Altar (51 - 120 AD)

[---]ius Ẹutych[es]/ [---? Pr]imae liberta

[--- qu]artus vicensimus annus/ [--- fl]ebilis hic titulus

There is no surviving evidence for the original location of the associated grave. Since the gravestone was re-used on this site close to the northwest boundary of the putative Roman city.

Possible Roman Burials near the Main Facade of the Duomo

Cross Largo Carducci and stop in front of the main facade of the Duomo. According to Michele Faloci Pulignani (referenced below, 1934, at pp. 9-10), a document in the archives of the Abbazia di Sassovivo recorded that, when this area was was excavated in 190, it was found to be occupied by bodies covered by large gabled tiles:

-

✴Guerini and Latini (referenced below, at p. 277, in entries 32 and 33) described them as “tombe a tegoloni” (entry 32) and dated them to the Roman period (entry 33), citing an earlier paper by Faloci Pulignani in which the latter opinion was presumably included. If this is correct, then the site could not be within Roman Fulginia.

-

✴However, Paolo Camerieri and Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2016, at p. 18, note 24) argued that these burials were more probably evidence of:

-

“... the presence in Foligno of the medieval practice of burial in front of churches” (my translation).

I discuss this important difference of view as part of my overall assessment of the evidence for the putative Roman city in the page on the Location of Roman Fulginia.

Inscribed Blocks in the Main Facade of the Duomo

According to Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1994, at p. 83):

-

“The large marble blocks [used for the inscription on the main facade of the Duomo, two of which are illustrated here], which are probably derived from recovered material, are perfectly squared and smoothed ...” (my translation).

He did not suggest a date for the original working of these blocks, but the position of the corresponding entry in the catalogue of Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 278, entry 36) suggests that they assumed a Roman date.

Roman Remains in the Crypt of the Duomo

Visitors usually visit the crypt of the Duomo from the Museo Diocesano, the entrance to which is via the steps to the left of the main facade (see above).

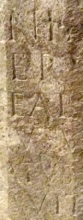

Roman Inscription (1st century AD)

Roman column Detail of the inscription

This fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 5209), which is now embedded in one of the columns of the crypt, reads:

VO[... et]/ [Iuno]ni R[eg(inae) et]/ [Min]erv[ae et]/ [dis d]eab[usque]

[...]ius M(arci) [f(ilius) ...]/ [... Sper]atus [...]/ [... po]suit [

This inscription, which commemorates Juno and Minerva (with Jove possibly originally included in the top line) seems to have come from a base of some sort, which had presumably been commissioned by “ ... ius ... Sperlatus, son of Marcus”. According to Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1985, at p. 312), the inscription:

-

“... was probably executed in the 1st century AD, as seems to be indicated by the form of the letters and the type of monument. The base might have supported a donario [donative altar] or a foculum [a small hearth used for sacrifices] used in the cult of the divinities [commemorated]. We are probably dealing with a gift offered in a local sanctuary, as seems to be indicated by the use of Apennine limestone, although we have no other data relating to its location” (my translation).

Giuliana Galli (as above) suggested (at p. 101) that this inscription is perhaps:

-

“... indicative of the divinity/ divinities to which the hypothetical temple could have been dedicated” (my translation).

Remains of Roman Columns

According to Giuliana Galli (referenced below, 2016, at pp. 98-9 and Figure 57) fragments of columns in the crypt of the Duomo, which I have not yet been able to photograph, (and others that are now in courtyard of Palazzo Trinci, discussed above) might have come from the putative temple on the later site of the left transept of the Duomo. The relevant Roman remains in the crypt comprise:

-

✴a fragment of a fluted column similar to the one in Palazzo Trinci;

-

✴four fragments of basalt columns.

Completion of the Walk Around the Putative Roman City

The rest of the walk is included for completeness, albeit that it adds nothing further to the arguments in relation to the possible Roman origins of modern Foligno.

Rest of the Northwestern Boundary (A-G)

Leave Piazza della Repubblica along Via XX Settembre (under the arch in the photograph above, to the left of the minor facade of the Duomo).

Turn right at the end and continue along Vicolo dell’ Oratorio to the junction with Via Gentile da Foligno: the northernmost point of the putative Roman city was to the left, a little way along the latter road.

Northeastern Boundary (G-H)

Continue to Via Garibaldi: if you look along it to the right, you will see that this is a continuation of Via Mazzini, and thus continues the line of the decumanus maximus of the putative Roman city.

Rest of the Southeastern Boundary (H-F)

Turn right along Via Pignattara and continue to the so-called Torre dei Vitelleschi at the end of the street: this was the site of a gate in the city walls of ca. 1240. Walk thorugh the arch into Corso Cavour: Via dell’ Oratorio, which you walked along earlier, is opposite , so you have completed the walk around the boundaries of the putative Roman city.

Via Quintana (again: F-A)

Turn right along Corso Cavour and Largo Carducci (following the putative Via della Quintana) into Piazza della Repubblica, where this walk ends.

Read more:

P. Camerieri, Giovanna and Giuliana Galli (Eds.), “Dal Castrum alla via Quintana, dal Tempio alla Cattedrale: Studi Topografici e Architettonici tra Ambiguità Storiche e Anomalie Urbanistiche”, (2016) Foligno:

P. Camerieri and Giuliana Galli, “Dal Castrum Romano alla Cattedrale: Rilettura della Passio Sancti Feliciani nel Contesto Topograico Castramentato di Foligno”, pp. 15-31

P. Camerieri, “Una Rilettura Topografica e Architettonica delle Vicende del Martire Feliciano e degli Edifici di Culto da Lui e a Lui Dedicati”, pp. 33-57

Giuliana Galli, “Ab Origine: Ipotesi sul Riconoscimento delle Persistenze Topografiche

e Architettoniche di un Tempio Pagano nel Sito della Cattedrale: la Fase d’ Età Romana (III sec. a.C.-III sec. d.C.)”, pp. 89-107

Giuliana Galli, “Valutazione Consuntive con Aggionamento dei Dati Topografico-Archeologici e Prospettive di Ricerca”, pp. 108-23

G. Galli (Ed.), “Foligno, Città Romana: Ricerche Storico, Urbanistico e Topografiche sull' Antica Città di Fulginia”, (2015) Foligno, includes:

✴G. Galli, “Foligno Città Romana: Considerazioni sugli Studi Topografici e sulle Emergenze Archeologiche”, pp. 35-74

✴P. Camerieri, “Il Castrum e la Pertica di Fulginia in Destra Tinia”, pp. 75-108

P. Guerrini and F. Latini, “Foligno: Dal Municipium Romano alla Civitas Medievale: Archeologia e Storia di una Città Umbra”, (2012) Spoleto

L. Sensi (Ed.), “Discorso di Fabio Pontano sopra l’ Antichità della Città di Foligno”, (2008) Foligno

V. Cruciani, “Mura e Città: Il Caso di Foligno nel Trecento”, (1998) Foligno

M. Torelli, “Studies in the Romanisation of Italy” (1995) Edmonton (English translation)

B. Lattanzi, “Storia di Foligno: Dalle Origini al 1305”, (1994) Foligno

L. Sensi, “Le Testimonianze dell’ Antico”, in:

G. Benazzi (Ed.), “Foligno AD 1201: La Facciata della Cattedrale di San Feliciano”, (1994), at pp. 81-7

V. Cruciani, “Foligno: la Pietra Racconta”, (1990) Foligno

L. Bonomi Ponzi, “Inquadramento Storico-Topografico del Territorio di Foligno”, in:

M. Bergamini (Ed.), “Foligno: La Necropoli Romana di Santa Maria in Campis”, (1988) Perugia, pp. 11-18

L. Sensi, “La Raccolta Archeologica della Cattedrale di Foligno”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 9 (1985) 305-26

D. Manconi, “Un Cippo Funerario Romano dalla Piazza Grande di Foligno”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 8 (1984) 501-2

L. Sensi, “Fulginia: Appunti di Topografia Storica”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 8 (1984) 463-92

W. von Sydow, “Ein Rundmonument in Pietrabbondante”, Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts: Römische Abteilung”, 84 (1977) 67-300

G. Dominici, “Fulginia: Questioni sulle Antichità di Foligno”, (1935) Verona

M. Faloci Pulignani, “Il Corpo e le Reliquie in San Feliciano Martire, Vescovo di Foligno” (1934), republished in:

G. Bertini and M. Sensi (Eds), “San Feliciano, Cattedrale di Foligno”, (2004) Foligno

L. Ross Taylor, “The Latina Colonia of Livy xl. 43”, Classical Philology, 16:1 (1921) 27-33

M. Faloci Pulignani, Foligno”, (1907) Bergamo

G. F. Pivati, “Nuovo Dizionario Scientifico E Curioso Sacro-Profano (Vol. 4)”, (1747) Venice

History of Fulginia: From Conquest to Municipalisation After Municipalisation

Location of Roman Fulginia Roman Walk I Roman Walk II Roman Walk III

Return to History of Foligno