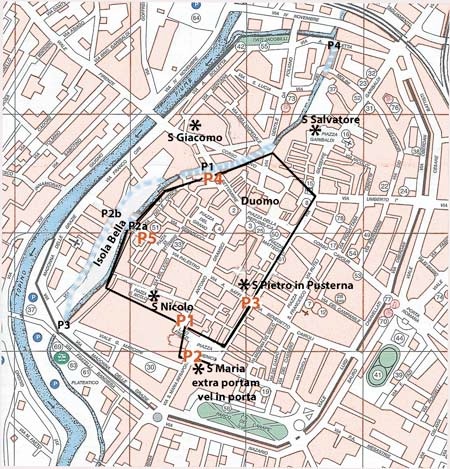

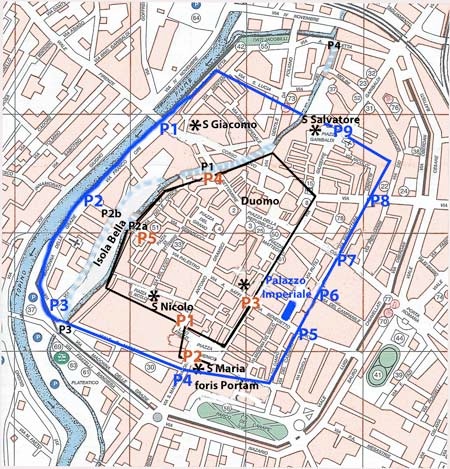

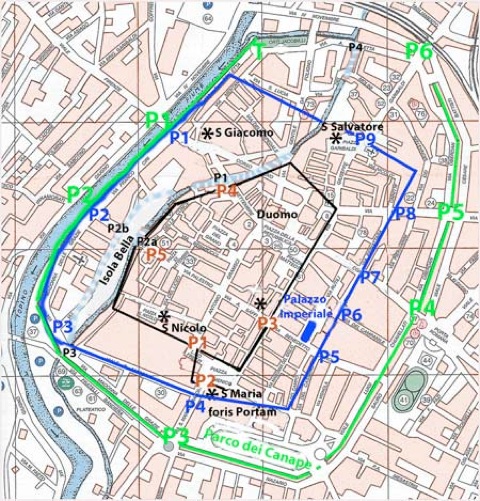

City Walls before ca. 1240

An early indication of the existence of city walls comes in a bull of 1138, in which Pope Innocent II reserved for the bishop of Foligno rents from (inter alia) the bridges and gates of the city. The existence of three specific city gates in this early period is implied by the names of two ancient buildings:

-

✴The church now known as Santa Maria Infraportas was documented:

-

•in 1087, when its hospice was designated “Hospitale Sanctae Mariae foris Portam”; and

-

•in 1207, as "Sancte Marie extra portam vel in porta".

-

Thus, this ancient church was outside a gate [P1] that apparently existed in 1087 and beside another [P2] that was built between 1087 and 1207.

-

✴The church of San Pietro in Pusterna, which first documented as San Pietro de Pusterla in 1213, presumably stood by a small city gate or pusterla [P3].

The earliest surviving explicit mention of city walls comes in a document dated 1217, which is in the archives of the Abbazia di Sassovivo. As noted by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 93 and note 373), it described a house in Borgo San Leonardo, near the church of San Salvatore, that was described as ‘extra murum civitatis’.

Guerrini and Latini (referenced below, at p. 95 and note 384) referenced an extract from the statutes of Foligno (ca. 1350) that referred to the buildings between the Porta Santa Maria foris Portam and San Salvatore as having been built on the “muros antiquos” (as opposed to the “muros veterus”, the term used for the walls of ca. 1240 (below). This suggests that the southeastern part of these walls, which presumably included [P3], ran roughly along the line of the present Via Mazzini. From there, it would have swung towards the northwest before reaching San Salvatore, which (as noted above) was outside the walls at this early date.

As noted in my page on the Bridges of Foligno, the Topino flowed through the city at this time, and was articulated by four bridges (Marked P1, P2a/b, P3 and P4) on the map above. According to Guerrini and Latini (referenced below, at p. 94):

-

“... it is possible that the [northwest stretch of the early walls] is attested along the original course of the Topino. Indeed, Vladimiro Cruciani [referenced below, at p. 29] has traced various stretches of wall along Via XX Settembre and Via delle Conce, and it seems plausible that these did not belong to the [later circuit, discussed below], which we know from documents included the suburbs north of the river” (my translation).

Two gates probably belonged in this part of the circuit:

-

✴Porta Strettura/ Porta San Jacobi [P4]; and

-

✴Porta della Spada/ Porta San Giovanni dell’ Acqua) [P5].

The wall presumably followed the river far before swinging towards the southeast, and would have enclosed the church of San Nicolò (which was described as in Civitas Fulineata in 1103) to the gate I have labelled [P1].

The circuit shown in the map above is essentially that represented by Guerrini and Latini (referenced below, at Table VII). In particular, I have followed these scholars in representing [P2] as an ante-port.

City Gates

Porta de Petitu/ Porta Santa Maria Vecchia [P1]

Guerrini and Latini: pp. 299-300, entry 77; and p. 317, entry 107

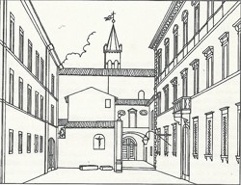

Vladimiro Cruciani: pp. 29-30 and Figure 8 (illustrated below)

From Vladimiro Cruciani (below) Figure 8

Fabio Pontano (1618), quoted by Guerrini and Latini at p. 108, note 431, recorded that:

-

“Inside the city, near the church of San Domenico, there is an ancient arch, which I think served as a gate of the city before its expansion” (my translation).

According to Ludovico Jacobilli (1646), as reported by Guerrini and Latini (in entry 107), the arch had been incorporated as the city walls of the 12th-13th centuries and was known as porta de Petitu. Giovanni Francesco Pivati (1747) described it as an ancient arch under the house of the noble Scafali family (at p. 377, search on ‘Scafali’ in the webpage).

Vladimiro Cruciani located this arch at the end of Via Gramsci, and suggested that it had been a minor gate in the early city walls. In his Figure 8 (reproduced on the left above), he sketched its location as it was in the 19th century (i.e. before the demolition of the building at the centre that is decorated with a Crucifix). In the legend to this figure, he described it as the “arco della famiglia Scafali”, which had been destroyed in 1781 to make way for Palazzo Brunetti Candiotti, the large palace to the right. The arch itself was thus absent in his sketch, but the pilaster at the right of the building with the Crucifix and the blocks in front of it had belonged to it. (My photograph, on the right, shows this location now, with the Oratorio del Crocifisso to the right of the arch on the right, and the right wall and campanile of San Domenico visible behind it).

Fortunately, both Fabio Pontano and Ludovico Jacobilli (as referenced above) recorded aspects of the appearance of this arch in the 17th century:

-

✴Fabio Pontano noted that this ancient structure:

-

“... was truly made in the shape of an arch and, next to it, there are two large pieces of ancient columns that I believe formed part of it: these are made in the Doric style, similar to the Arch of Titus in Rome. ... The structure [in Foligno] is made of stone that is of great antiquity, but these have been taken from earlier structures, particularly from funerary structures. This is evident from the left side of the arch, where a standing man faces the church: on one of the large stones here, one can read [a Roman funerary inscription]” (my translation).

-

✴Ludovico Jacobilli noted that the structure included:

-

“... worked Roman stones and a stone sculpture of Pan” (my translation).

-

This figure of “Pan” presumably corresponds to Pontano’s standing man facing San Domenico.

It seems to me that Pontano’s funerary inscription by no means proves that all of the stones in the reconstituted arch came from funerary monuments. Indeed, many of its components must have come from an earlier arch of similar form and dimensions and, since there is no mention of any non-Roman components, this was presumably a Roman arch.

The reconstituted arch almost certainly stood here in 1087, when, according Ludovico Jacobilli, the “Hospitale Sanctae Mariae foris Portam” (the hospital of the church known as Santa Maria outside the gate) was mentioned in a now-lost document in the archives of the Abbazia di Sassovivo.

-

✴The gate might (as Pontano and Jacobillili assumed) have been part of an early circuit of walls. This is accepted by Vladimiro Cruciani (in his Figure 48, p. 74) and by Guerrini and Latini (in their Table VII, where it is marked 107).

-

✴In my view, it might originally have been reconstituted as a free-standing structure at some time before 1087, perhaps a ceremonial entrance to the then-unwalled city.

Porta Santa Maria [P2]

Guerrini and Latini: the church is described at pp. 299-300 entry 77; and the gate at pp. 317-8, entry 108

Vladimiro Cruciani: p. 29

Karl Schubring: Figure 1, number 2

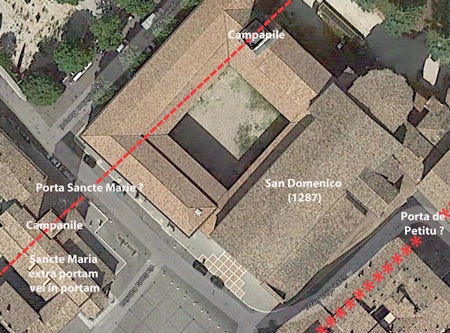

Churches of: Santa Maria Infraportas (to the left); and San Domenico

Present church of Santa Maria Infraportas (lower left),

documented as: “foris portam” in 1087; and “extra portam vel in porta” in 1207

In 1990, the Corriere dell’ Umbria reported that a short stretch of wall had been discovered during work in Via di Santa Maria Infraportas, the street that runs between the right side of the church of Santa Maria Infraportas and the ex- convent of San Domenico. This wall was aligned with the campaniles of both Santa Maria Infraportas and San Domenico (both of which can be seen in the photograph above and are indicated in the aerial view below it). Guerrini and Latini (in entry 108) quoted Giovanni Bosi, the author of the newspaper article, who apparently had first suggested that a stretch of walls here had connected these two towers:

-

“In favour of this hypothesis is the anomalous position of the campanile of San Domenico, which is totally separate from the church” my translation).

The suggestion is that the builders of San Domenico in ca. 1285 had used a tower in the (by then demolished) city walls as the base of its campanile.

-

✴Vladimiro Cruciani (see his Figure 48, p. 74) placed both this gate and Porta de Petitu in the same 13th century circuit.

-

✴Guerrini and Latini (in their Table VII) represented it as an ante-porte of the early walls.

-

✴Karl Schubring (who did not mention Porta de Petitu) identified it as a gate in the early walls that he called the Porta Sancte Mariae.

Pusterla [P3]

Guerrini and Latini: pp. 298-9, entry 76

Vladimiro Cruciani: p. 29; p. 30, Figure 8; p. 96, Figure 67

Porta Strettura/ Porta San Jacobi [P4]

Guerrini and Latini: p. 316, entry 105

Vladimiro Cruciani: p. 29; p. 96, Figure 67

Karl Schubring: p9 and Figure 1, number 9

Ludovico Jacobilli (quoted by Guerrini and Latini in entry 105) recorded that this gate was built:

-

“... of ancient stones, with a tower above, at the end of the street named Strettura, ... not far from the Ponte di Cesare [P1], now called Ponte della Pietra ...” (my translation).

According to Vladimiro Cruciani, it was demolished in 1880, when Via XX Settembre was widened in order to improve the access to Piazza San Giacomo. However, he identified remains of the adjacent city walls at numbers 47 and 52 Via XX Settembre.

As noted above, Guerrini and Latini pointed out that this wall must have belonged to an early circuit, before the suburbs across the river were enclosed. Karl Schubring placed two gates in the early walls here:

-

✴this one leading to the Ponte di Cesare, which he identified as Porta Sancte Jacobi (see below); and

-

✴the nearby Porta Sancte Margarite (his number 10), which he placed slightly to the southwest, outside the church of Santa Margherita, opposite another bridge across the Topinello. This gate had apparently been documented in 1291.

Porta della Spada/ Porta di San Giovanni dell’ Acqua) [P5]

Guerrini and Latini: p. 317, entry 106

Vladimiro Cruciani: p. 29; p. 96, Figure 68

Karl Schubring: Figure 1, number 1

According to Vladimiro Cruciani (as above), a second stretch of walls along the Topino that was incorporated into the terraced houses in Via delle Conce extended to the now-demolished Porta della Spada, near the church of San Giovalli dell’Acqua. Ludovico Jacobilli (quoted by Guerrini and Latini in entry 106) recorded that vestiges of this gate, which he called “Porta Spataria o della Spada”, could still be seen in the 17th century, contiguous with the church of San Giovanni dell’ Acqua. Cruciani illustrated the remains of this gate in the facade of a house near the church [address ??].

Ghibelline Walls (ca. 1240)

__________ P: Walls and Gates of ca. 1240

According to Karl Schubring (referenced below, at p. 9), plans for this new circuit of walls were taking shape by 1232, when work began on the surrounding moat. However, the plans were presumably accelerated in 1239, when Foligno joined the Ghibelline alliance that supported the excommunicated Emperor Frederick II against Pope Gregory IX. As Mario Sensi (referenced below, at pp. 400-12) recorded, Frederick II held a parliament of his allies in the Duomo of San Feliciano (9th February, 1240). He then appointed Giacomo di Morra as Captain General of the Duchy of Spoleto, and he in turn nominated Rufino da Lodi as his “iudex et vicarius” for Foligno. It was apparently at this time that the building of a new circuit of city walls began in earnest.

There are three main sources for the location of the walls and gates of ca. 1240:

-

✴Mario Sensi (referenced below, at pp. 417-23) published a surviving extract from the city archives that related to this project of fortification (which unfortunately only covered a few weeks in the spring of 1241). It listed a number of contracts agreed under the auspices of Bernardo di Custode, the city treasurer in which representatives of the city districts commissioned and undertook to finance the work of specified artisans on the part of the wall for which they were responsible. As Mario Sensi noted (at p 407), these contracts only provide two indications of the course taken by the new walls:

-

•on 22nd April, the representative of the district of ‘ Picciano’ undertook to deliver bricks to the “porta Abbatie” (probably P5); and

-

•on 24th April 1241, Bernardo promised to supply materials for the “Porta S. Iohannis de Aqua” and a stretch of walls from this gate to “Porta dei Cippischi” (probably, respectively, P2 and P3).

-

✴According to Ludovico Jacobilli (in his Chronicle of Foligno, quoted by Mario Sensi at p. 408), in 1240:

-

“The Ghibelline administration fortified the city of Foligno, surrounding with new walls the suburb of Poelle and all the houses towards Perugia on the far side of the river” (my translation).

-

This move was clearly made in anticipation of attack from Guelf Perugia. The likelihood is that the wall enclosed the Isola Bella as well as the adjacent district of Poelle, and that it roughly followed the course presently taken by the Topino and included the “Porta S. Iohannis de Aqua” and a stretch of walls from this gate to “Porta dei Cippischi” (probably, respectively, P2 and P3) documented in 1241.

-

✴The circuit of walls to the southeast, which enclosed the new administrative centre known as the “palatium imperiale”, was subsequently documented in relation to the establishment of the new Franciscan convent here in 1255. As discussed below, these documents referred to the Porta Abbatis and Porta San Matteo (respectively, P5 and P6).

Porta Nova Sancti Jacobi [P1]

Guerrini and Latini:Table VIII, number 3

Karl Schubring: Figure 2, number 9

Karl Schubring (referenced below, at p. 11) mentioned (without references) the existence of this gate in this circuit of walls, near the house of the nuns of Sancte Maria de Caresta (Santa Maria Casta). The existence of this gate, northwest of the older Porta Strettura/ Porta San Jacobi [P4] above, is entirely plausible.

Porta (Nova) Sancti Johannis de Aqua [P2] and Porta Cippiscorum [P3]

Guerrini and Latini: Table VIII, numbers 2 and 1 respectively

Karl Schubring: Figure 2, numbers 1 and 2 respectively

As noted above, in a contract signed on 24th April 1241, Bernardo di Custode, the city treasurer, undertook to supply materials for the “Porta S. Iohannis de Aqua” and a stretch of walls from this gate to “Porta dei Cippischi”. This suggests that, while the first of these gates was in construction, the second had already been completed.

-

✴The existence of the first of these, northwest of the older Porta di San Giovanni dell’ Acqua [P5] above, is entirely plausible.

-

✴So too is the suggestion of Karl Schubring (referenced below, at p. 10) that the second of these gates, Porta Cippiscorum, was probably also on the north side of the river.

Porta (Nova) Sancte Maria [P4]

Karl Schubring: Figure 2, number 3

According to Karl Schubring (referenced below, at p. 10):

-

“...although it was never mentioned in documents, a new gate was built on, or at least planned for, a site in front of Santa Maria Infraportas ...”

He placed this new gate slightly to the south of the the older Porta Santa Maria [P2].

I must confess that I do not understand the basis of this statement (probably because of my poor Italian) . However, as discussed below, I think it this new gate was documented in 1285 (in connection with the establishment of San Domenico) as the Porta Nova, on the road from the Platea Santa Maria foris Portam that first passed the older gate.

Porta Abbatis [P5] and Porta San Matteo [P6]

Guerrini and Latini: pp. 319-20, entry 111; and p. 319, entry 110 respectively

Table VIII, numbers 8 and 7 respectively

Vladimiro Cruciani: Porta San Matteo is mentioned at p. 29

Karl Schubring: Figure 2, numbers 4 and 5 respectively

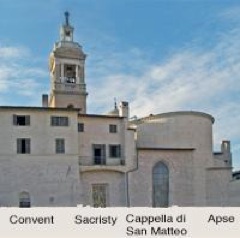

Rear view of San Francesco

After the Guelf victory over Foligno in 1254, which (as discussed below) led to the destruction of the city walls, the Friars Minor of Foligno took possession of the imperial palace and the nearby church of San Matteo. The transfer document of 1256 (quoted by Guerrini and Latini at p. 103) described the boundary of the new Franciscan complex as formed by:

-

✴a road that ran from Porta Abbatis to the ‘Trivium Franciscorum”;

-

✴the new moat; and.

-

✴the road that ran from Porta Abbatis to Porta San Matteo.

These two gates had presumably formed part of the newly-demolished walls:

-

✴As noted above, a gate called e “porta Abbatie” had been documented in 1241. The topographical information above suggests that it was in what is now Via Cairoli.

-

✴The church of San Matteo was incorporated into the present church of San Francesco as the Cappella di San Matteo, and remains of what seems to have been the Porta San Matteo still survive in the wall of the adjacent sacristy (illustrated by Vladimiro Cruciani, at Figure 72).

Porta San Constantii/ Porta vetus Contrastanghe [P7]

Guerrini and Latini: p. 320, entry 112; Table VIII, number 6

Vladimiro Cruciani: pp. 30-1, as “porta-torre detta dei Vitelleschi”

Karl Schubring: Figure 2, number 6

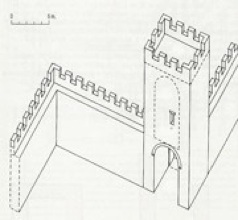

Reconstruction of the “porta-torre detta dei Vitelleschi”

From Vladimiro Cruciani (Figure 1o)

The so-called Torre dei Vitelleschi at the end of Via Pignattara originally formed part of the walls of ca. 1240. The remains of the Porta San Constantii (also known as the Porta vetus Contrastanghe) are still clearly visible at the base of this tower (to the right in the photograph above).

Porta Antica della Croce [P8]

Guerrini and Latini: pp. 320-1, entry 113

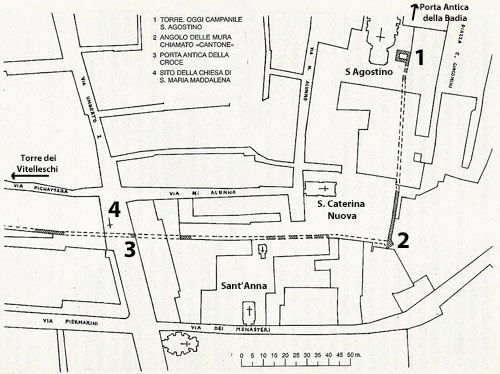

Vladimiro Cruciani: pp. 31-3; p. 38, Figure 15 (illustrated below); p. 101, Figure 77

Karl Schubring: Figure 2, number 7

From Vladimiro Cruciani, Figure 15

According to Ludovico Jacobilli (quoted by Guerrini and Latini, referenced below, at p. 110, note 433):

-

“In times gone by, the church [of Santa Maria Maddalena, which is now in Via Umberto I] was next to the city gate known as ‘della Croce’, from which one travelled to Rome. ... today, only vestiges of this gate remain, between the secondary entrance to [Santa Maria Maddalena] and the walls of the orchard of the nunnery of Sant’ Anna” (my translation).

The plan above shows the site of the Porta Antica della Croce (3), near the site of church of Santa Maria Maddalena (4) and the junction of Via Pignattara and Via Umberto I.

Porta Antica della Badia [P9]

Modern Porta Ancona or Porta Loreto (demolished ca. 1930)

Guerrini and Latini: Table VIII, number 4 (Porta Abbatiae)

Vladimiro Cruciani: p. 33 and p. 154, note 21

Karl Schubring: Figure 2, number 8 (Porta Sancti Leonardi)

According to Vladimiro Cruciani (at note 21), this gate:

-

“... also called Porta Sant’ Agostino opened in the old walls, perhaps near Piazza San Salvatore [now Piazza Garibaldi] Its exact location is not known” (my translation of note 21).

This later name was documented in the city statutes of ca. 1350 (reproduced by Guerrini and Latini, referenced below, at p. 95, note 385), which related to a canal:

-

“... near Porta S. Agostino, ... next to the old city walls” (my translation).

New City Wall (ca. 1282)

The Ghibellines were weakened by the death of Frederick II in 1250 and soon faced an attack from Perugia. According to the ‘Cronaca’ of Bonaventure Benevenuti, in 1253:

-

“... when the Perugian army laid siege to Foligno for seven weeks and diverted the river towards Spello, water appeared in the well in the platea veteris, outside the Duomo. When the army withdrew and the river returned to its original course, the water in this well disappeared” (my translation).

The war however continued into the following year, when Foligno was forced to sign a peace treaty with Perugia on profoundly humiliating terms: the authorities were required to accept the hegemony of Perugia and to demolish the walls, to fill in the defensive ditches, and to refrain from building new fortifications.

Despite this setback, Foligno recovered economically, and the Ghibelline party was able to recover its position to some extent. The chronicle of Bonaventura di Benvenuto recorded that Foligno suffered from a severe earthquake in 1279. Subsequent entries suggest that this provided an opportunity for the construction of a new defensive infrastructure:

-

✴In 1280:

-

“A new moat was made around civitas Fulginia” (my translation); and

-

✴In 1281:

-

“Bridges were made over the river, near the [new] moats” (my translation).

Karl Schubring (referenced below, at p. 11) quoted a document of 1282 in which Pope Martin IV noted the complaints of the Perugians about the

-

“ ... moat and walls ... built around the city” (my translation).

Perugia demanded their demolition, but Foligno was able to resist, not least because of the support of Martin IV. (Foligno protected its position by naming him as Podestà throughout the period 1284-6). However, despite the subsequent support of his successor (Pope Nicholas IV), Foligno was forced to submit to Perugia in 1289 and to destroy its walls and moats all over again.

The documents describing the establishment of two new religious orders in the city throw some light on this new defensive project:

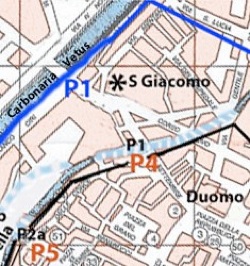

San Giacomo (1273)

In the document in which Bishop Paparone transferred the church of San Giacomo to the Servites, the location of this church was described as:

-

“... above ... the pons Cesaris [P1] adjoining [the suburb known as] Poelle, between the ‘carbonariam veterem Civitatis Fulginei’ and the Topino as it flows near the gate of the aforementioned city” (my translation).

By this time, the walls of ca. 1240 and the gate [P1] had presumably been demolished. Guerini and Latini (referenced below, at p. 104) suggested that the ‘carbonaria vetus’ (the moat outside these walls) still protected the suburb of Poelle, north of the river. The gate near the Topino mentioned in the document would have been the Porta Strettura [P4], from the earlier walls, perhaps alternatively known as the Porta San Jacobo.

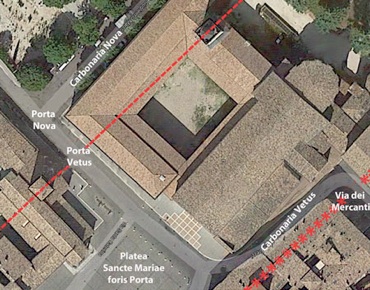

San Domenico (1285)

The chronicle of Bonaventura di Benvenuto recorded that:

-

“The Friars Preachers [i.e. the Dominicans] came to Foligno [in 1285] and began the place [i.e. their convent] near the Plateam Sanctae Mariae” (my translation).

The document of that year (reproduced in the website) in which Pope Honorius IV confirmed the transfer of land for the church and convent of San Domenico specified the site:

-

“...at the end of Via dei Mercanti [now Via Gramsci], near the gate and piazza of Santa Maria foris Portam, outside the city walls, [bounded by]:

-

✴the street that runs from [this piazza] to the ‘portam veterem civitatis Fulginatis’ and on to the ‘portam novam’, which stands in the carbonaria nova ...;

-

✴the carbonaria nova;

-

✴... the carbonaria vetus ... ; and

-

✴[a number of private properties]

Thus, it seems that, although the walls of ca. 1240 had been demolished, the corresponding moat and the gate here [P4] (now the Porta Nova) survived. So too did the earlier gate [P2], now the Porta Vetus. Since the site was now outside the city walls, it seems that the walls that must one have abutted the Porta de Petitu [P1] at the end of Via dei Mercanti had been rebuilt.

Later City Walls (1329)

Detail of fresco (1467) by Pierantonio Mezzastris, Madonna della Fiamenga

War between Perugia and Foligno erupted again in 1305. Perugia, with its allies from Spoleto and the Guelf exiles from Foligno, took the city. The leading Ghibelline were exiled and the Perugians installed Rinaldo (Nallo) Trinci (1305-21) as Capitano del Popolo. This marked the start of the period of Trinci rule of Foligno, which was to last until 1439.

Despite Foligno’s subsequent loyalty to Perugia and the fact that its exiled Ghibelines remained a threat, Perugia refused permission for the construction of a new city walls in 1312. The authorities had to be content with the amplification of the system of defensive ditches around the city. Thus, the chronicle of Bonaventura di Benvenuto recorded that, in 1319:

-

“The Fulginates began to make a new moat around the city” (my translation).

When Rinaldo Trinci died in 1321, his brother, Ugolino I Trinci, succeeded him as leader of the Guelf party and Gonfaloniere di Giustzia. In 1328, Ugolino foiled a surprise attack on the city by the Emperor Louis of Bavaria. After this scare, it seems that the Perugians relented: the chronicle of Bonaventura di Benvenuto recorded that, in 1329:

-

“The city wall was begun at the new moat, near Ponte Cavallo” (my translation).

Ponte Cavallo was an an alternative name for pons Cipiscorum, the bridge that seems to have been built in 1281 to the south west of the Porta Cippiscorum [P3].

It is clear from the substantial remains of this wall that:

-

✴the Topino had been diverted into present course, presumably in 1319, in order to run along the northern section of the projected circuit; and

-

✴it tributary, the Menotre, filled the new moat around the rest of the circuit.

New City Gates

Porta San Giacomo [P1]

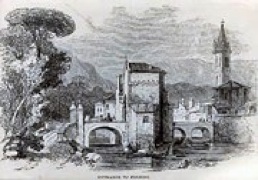

Entrance to Foligno (19th century)

This city gate (also known as Porta Firenze) opened onto the Ponte San Giacomo. As illustrated in the engraving above of a water colour (1837), which appeared in the Art Journal and is now in a British private collection, this bridge had a bastion in the middle, which probably served as an anti-porte for defensive purposes and possibly also as a customs barrier. The bastion was demolished and the bridge took on its present form in the engineering work that Antonio Rutili Gentile undertook after the flood of 1836.

Porta San Giacomo, which was illustrated by Giovanni Bosi (referenced below, at p. 76) in its 18th century guise, was demolished in 1927. However, a well-preserved tract of the new walls still runs in both directions along the river bank (along Via Bolletta and Via Ciri. (Part of the latter stretch is visible to the right in the photograph above).

Porta San Claudio [P2]

Porta Todi [P3]

Parco dei Canape

Porta Romana [P4]

Panel (17th century) by Ascensidonio Spacca , Pinacoteca Civica

Porta San Felicianetto [P5]

The gate was closed in the 18th century and converted into a large aedicule with a fresco that presumably depicted St Felician. It was returned to something like its original appearance in 1920, by which time the walls immediately adjacent to the gate had been demolished.

This gate is the only one to survive in the outer circuit of walls. Stretches of these walls can be seen to each side of it. The canalised Menotre river, which ran along this section of the walls, was diverted underground in 1989.

Porta Badia [P6]

Torre dei Cinque Cantoni (1456) [T]

Read more:

G. Galli (Ed.), “Foligno, Città Romana: Ricerche Storico, Urbanistico e Topografiche sull' Antica Città di Fulginia”, (2015) Foligno:

G. Galli, “Foligno Città Romana: Considerazioni sugli Studi Topografici e sulle Emergenze Archeologiche”, pp. 35-74

P. Camerieri, “Il Castrum e la Pertica di Fulginia in Destra Tinia”, pp. 75-108

P. Guerrini and F. Latini, “Foligno: Dal Municipium Romano alla Civitas Medievale: Archeologia e Storia di una Città Umbra”, (2012) Spoleto

V. Cruciani, “Mura e Città: Il Caso di Foligno nel Trecento”, (1998) Foligno

M. Sensi, “Un Palatium Imperiale a Foligno e un Castrum Imperiale a Spello in Età Federiciana”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno", 20-1 (1996-7) 393-424

K. Schubring, “Foligno e le Sue Mura Civiche dal Duecento fino ai Nostri Giorni”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno", 17 (1993) 7-18

G. Dominici, “Fulginia: Questioni sulle Antichità di Foligno”, (1935) Verona

Return to the page on Monuments of Foligno.