Location of Roman Fulginia

Michele Faloci Pulignani (in a publication of 1936, quoted by Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini, referenced below, at p. 75, note 291) observed that:

-

“The land on which our city of Foligno was built is virgin land and, however extensively it is excavated, ... important remains of ancient buildings ... are never brought to light. In contrast, every time one moves the earth near the church of Santa Maria in Campis, one finds ancient objects of all kinds ...” (my translation).

Thus, he believed that Roman Fulginia had been located, not on the “virgin soil” of medieval and modern Foligno, but in what is now the suburban area around Santa Maria in Campis, a kilometre from the modern city, on the eastern branch of Via Flaminia.

This view has a considerable pedigree: for example, according to Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1984, at p. 463), the humanist Cesare Conti, who was writing in the second half of the 16th century, asserted that the churches of:

-

✴the Madonna del Sasso; and

-

✴Santa Maria in Campis (which he called Santa Maria Maggiore);

marked the extreme ends on the archeological area of the city. Conti noted that:

-

“In the flat area [between these two churches], which has been excavated many times, have been found ancient objects, underground rooms, medals ...”

In this walk (Roman Walk I), I explore the surviving evidence for the hypothesis that Roman Fulginia was in this location.

This view was first seriously challenged in the 1930s by Giovanni Dominici (referenced below), who alternatively placed Roman Fulginia on the site of modern Foligno. It is probably fair to say that this long remained a minority view. However, Giuliana Galli and Paolo Camerieri (in separate articles in the books referenced below of 2015 and 2016) have recently revived and refined it:

-

✴In my page Roman Walk II, I suggest a walk around this putative Roman city on the site of modern Foligno, concentrating on the surviving evidence within its boundaries; and

-

✴in Roman Walk III, I explore the potentially complementary evidence that relates to the origins of the nearby four bridges that once spanned the Tinia/ Topino.

I attempt to evaluate the results of all three explorations in my page on the Location of Roman Fulginia.

Walk around Santa Maria in Campis

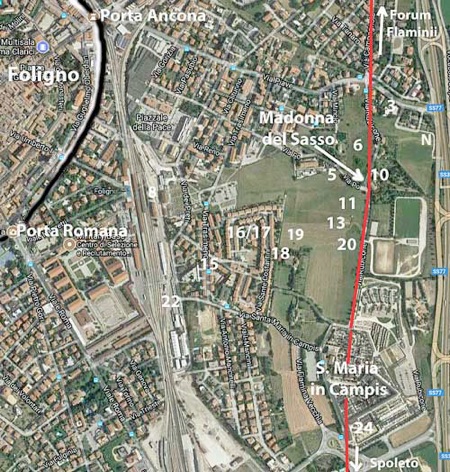

Archeological area at Santa Maria in Campis: the numbers assigned to important sites

are taken from Matelda Albanesi (referenced below, 2014, Figure 1)

This walk starts at the end of Via Garibaldi, on the site of Porta Ancona (demolished in 1930). The first part of it, from the old site of Porta Ancona along Via Piave to the city limit, is described in Walk III. The ‘Roman’ part of the walk, described here, then takes you round the main sites within the archeological area of Foligno. It begins at the city limit in Via Piave (near Site 3, towards the upper right in the plan above) and follows the line of Via Flaminia southwards from the site of the ex-church of Madonna del Sasso towards Santa Maria in Campis. It then takes in the other archeological sites to the west, as you begin the walk back towards Foligno.

Necropolis [N]

The walk starts (at the city limit in Via Piave) with a short, optional detour to the site N (which is just off the edge of the plan of Matelda Albinesi, referenced above, and hence given a letter rather than a number): continue out of Foligno and turn right just before the junction with the busy SS3: as this road swings to the right, take the path to the left, back towards the SS 3.

A small necropolis that was discovered here in 1998 contained 17 inhumations, almost all of which were in ‘tombe a cappuccina’ (tombs composed of a gabled tile roof covering the deceased, who was laid on bare earth or on a tile floor). According to Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 275, entry 27) this necropolis was in use in the 1st - 4th centuries AD.

Domus and Baths in Via Piave [3]

Guerrini and Latini: p. 266, entry 10

Return to the city limit, the sign for which is just visible on the right in this photograph. The vacant site on the left of Via Piave here (marked [3] on the plan map above) was once the orchard of a property in Via Rubicone (below) that belonged to the Marchionni family. The remains of a Roman domus were found here in 1934, during horticultural work. These remains included a large number of fragments from the mosaic flooring of a number of rooms. The domus itself probably dated to the 1st century AD, while the more ‘modern’ mosaic probably belonged to a restoration of the 3rd century AD. Unfortunately, the surviving remains of this mosaic, which featured a representation of the seasons and a battle between a lion and a horse, were later destroyed, probably during the bombardment of Palazzo Trinci during the Second World War. A polychrome mosaic of marine subjects (including a representation of the ancient Greek god, Oceanus) that was unearthed here in 2008 suggests that this domus had a private bathing area. [Where is it now ??]

Fosse Renaro

Ampitheatre/Circus and Theatre ? [6 and 10]

Guerrini and Latini: p. 263, entry 5

Turn left along Via Rubicone, which roughly follows the line of the eastern branch of Via Flaminia, towards Spoleto (outlined in red on the photograph). Continue to the junction with Via Po and look back.

The curved facade of Villa Sassonia (late 16th century) at number 7 on the right originally belonged to the Giusti Orfini family. According to Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1984, at p. 464), the church of the Madonna del Sasso had been built in front of this villa in the 16th century, on the site of an image of the Madonna that protected the locals from flooding by the Fosso Renaro (above). At the time at which Luigi Sensi was writing, this church had recently been demolished.

Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1984, at pp. 465-6) pointed out that the site opposite the Villa Sassonia [6] has been identified as that of a circus or amphitheatre since the 16th century. However, he observed that:

-

“... what is currently visible is only a piece of wall with a cement core that does not allow us to evaluate the true extent of the structure, which certainly must have been ... more evident [in the 16th century]. There is nothing, however, that rules out the possibility that an amphitheatre ... is to be located in this area” (my translation).

More recently, Laura Bonomi Ponzi (referenced below, 1988, at p. 16) reported that:

-

“A recent analysis of aerial photographs has revealed traces of a large elliptical building, probably an amphitheatre, [opposite Villa Sassonia], with its major axis measuring about 83 meters: a stretch of wall on its south side, in excellent opera cementizia, was brought to light some years ago” (my translation).

Unfortunately, this site is now very overgrown, and it is no longer easy (possible?) to identify these remains.

Laura Bonomi Ponzi (as above) also observed that:

-

“... the plan of [Villa Sassonia itself], in both land registry maps and aerial photographs, resembles in a unique way that of a theatre , so it is likely that it served this function” (my translation).

Maria Laura Manca (referenced below, pp 9-10) agreed:

-

“The remains of an annular wall in opera cementizia [opposite Villa Sassonia] suggest the site of an amphitheatre on Via Rubicone [as above], while the form of Villa Sassonia [itself] suggests the site of a theatre” (my translation).

However, Guiliana Galli (referenced below, 2015, at p. 71) argued that Villa Sassonia itself was the more likely candidate for an amphitheatre:

-

“The structure of ... Villa Sassonia, with a curvilinear wall along its southern side, more probably hides the remains of an amphitheatre, rather than those of a theatre. ... Alternatively, there could have been a circus here, the curvilinear structure of which later [underpinned Villa Sassonia]” (my translation).

She saw no evidence for a theatre here. Instead, she proposed (at p. 70) a site in the modern city, which she believed was where Fulginia itself was to be found.

Umbrian Necropolis [5]

Guerrini and Latini: pp. 269-70, entry 16

Grave goods from Via Po (Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci)

Take a short detour by turning right along Via Po as far as the end of the fence on the left (which encloses the archeological area - see below). Six tombs (6th – 5th centuries BC) that were discovered here in 1976 belonged to an Umbrian necropolis. Grave goods from this necropolis are exhibited in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci (Room 6). The discovery of the small votive bronze in nearby Piazza Risorgimento (see below) suggests that there was a sanctuary associated with this necropolis.

Archeological Area

View of Foligno from the Archeological Area

Return to and turn right along Via Rubicone, following the eastern branch of Via Flaminia towards Santa Maria in Campis. The fenced field on the right (illustrated above) defines a designated archeological area. Maria Laura Manca (referenced below, at pp. 9-10) summarised the conventional view of its significance:

-

“The urban area [of Roman Fulginia] is traditionally located principally along Via Rubicone, within a vast area between Santa Maria in Campis and Via Po that has recently been acquired by the Comune di Foligno and destined to become an archeological area. [Earlier] excavations here ... have unearthed [Roman] residential complexes ...., thermal complexes and roads” (my translation).

The sites of these individual discoveries are marked on the archeological map above.

Roman Buildings [11, 13 and 20]

Guerrini and Latini, respectively, p. 269, entries 15 and 14; and p. 271, entry 20

Laura Bonomi Ponzi (referenced below, at p. 16) reported on excavations carried out on these three sites in the archeological area of Via Rubicone on two separate occaions:

-

✴in 1974, on my sites 11 and 13 (respectively 9 and 8 in Bonomi Ponzi’s Table 1); and

-

✴in 1987 on my site 20 (Bonomi Ponzi’s 17).

The results have only been published in summary form:

-

✴According to Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (as above), the excavations in 1974 unearthed buildings that had been abandoned in the 3rd century AD and subsequently used for burials.

-

✴Laura Bonomi Ponzi (as above, at note 20) noted that the excavations of 1987 had been prompted by:

-

“... the fortuitous discovery of an early medieval sarcophagus [discussed below] ... probably datable to [ca. 300 AD] ... [It] occupied the remains of an edifice that was, in all probability, pertinent to the urban area and is ... [tentatively] dateable to the 2nd century AD” (my translation).

Laura Bonomi Ponzi (referenced below, at p. 16) summarised the consolidated results of these excavations as follows:

-

“The stratigraphy that emerged ... shows clearly that the [Roman buildings found here] were abandoned as early as the 3rd century AD, when inhumation in pits or in amphorae took place within their walls. The area continued in funerary use into the early medieval period” (my translation).

This apparent abandonment of site was consistent with the pattern of use of the Roman necropolis near the church of Santa Maria in Campis (below): according to Margherita Bergamini (referenced below, at p. 26):

-

“No evidence has been found to date for the use of the necropolis after [the late 3rd century AD]” (my translation).

Following further excavation of site 13 in 2006, Matelda Albanesi (referenced below, 2014, at pp. 560-1) modified the hypothesis that the residential settlement in this area had been abandoned as early as the late 3rd century AD. Specifically, she established (at p. 560) that at least part of the complex on this site had been in commercial use, and identified:

-

“... a consistent expansion of the original buildings towards the south, which involved the construction of three rooms within an area of the existing complex that had probably [originally] been open or otherwise free of buildings” (my translation).

She concluded (at p. 561) that:

-

“The date of the extension is indicated by ... [construction techniques] that were in use in late antiquity. This extension does not coincide with the abandonment of the original buildings of the imperial period, which continued in use ... ” (my translation).

Objects found during these excavations, which included a number of lamps from the early Christian period, also suggested that the complex had remained in commercial use into the late 4th and perhaps the 5th centuries. Matelda Albanesi concluded that these results require us:

-

“... to revise the hypothesis of a total abandonment of the area of [Santa Maria in Campis in the 3rd century AD] ...” (my translation).

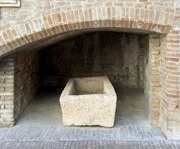

Sarcophagi from the area

Matelda Albanesi (referenced below. 2014, at p, 562-3 and notes 11 and 12) also argued that the former residential/commercial areas of Santa Maria in Campis began to be used for funerary purposes only (towards the end of late antiquity. She derived this dating from three sarcophagi found in the area, two of which (illustrated above) still survive in the courtyard of Palazzo Trinci:

-

✴one of these (which I think is the one on the right above) was found at my site 20 in 1987; and

-

✴the other was from San Feliciano di Mormonzone, a few kilometres to the east along Via Flaminia (see below).

Paleochristian sarcophagus from Santa Maria in Campis (destroyed in 1994)

Photograph from Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1982, p. 32, Figure 1)

Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1982) described the third of these sarcophagi, which was discovered in the late 19th century at an unspecified location near Santa Maria in Campis, and which had survived in the courtyard of Palazzo Trinci until it was restroyed in the bombardment of 1944. It had been first documented in the civic collection in 1893, and he suggested that it had probably been discovered in the area of the cemetery that had been established next to the church in 1867. He pointed out that the geometrical relief on its side had been used on perhaps five other sarcophagi from Umbria and the Marche, three of which had been re-used for the relics of saints: St Felix of Giano, St Juvenal of Narni and St Pontian of Spoleto. Matelda Albanesi (at p. 563) dated this sarcophagus from Foligno to the early 6th century AD.

In the light of her excavations at site 13 and her analysis of these three sarcophagi, Matelda Albanesi concluded (at p. 562) that:

-

“Only at the end of the period of late antiquity was this [previously urban] area used for funerary purposes” (my translation)

Santa Maria in Campis

Turn left on leaving Santa Maria in Campis, taking the road that runs along the wall of the civic cemetery. These brick walls enclose the cemetery that was established here in the 19th century, while the area beyond belongs to an extension made in 1970.

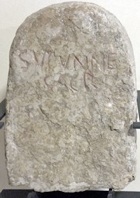

Inscription (ca. 200 BC)

The inscription, which uses the Latin alphabet, reads:

SUPUNNE

SACR

It is not clear whether the language is Umbrian or Latin, but it is likely that the cippus marked the boundary of an area that was sacred to an otherwise unknown goddess, Supunna. Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below, at p. 134) reproduced the early records of this inscription and the two main hypotheses relating to the identity of Supunna:

-

✴Alberto Calderini (referenced below, at p. 63) revived the traditional hypothesis that she was a river goddess (since ‘Supunna’ might associated with the ‘Tupino’, the Topino river of Foligno); this would be similar to the case of Clitumnus, a god associated with the nearby river of that name).

-

✴Paolo Vitelozzi (referenced below) referred to the hypothesis that the etymology suggested an old Latin verb “to throw”, which might indicate that Supanna was a goddess who presided over the preparation of food in the course of rituals of sacrifice.

This inscription is also described in the page on Umbrian Inscriptions after 295BC.

Roman Necropolis and Via Flaminia [24]

Guerrini and Latini: p. 267, entry 11

Traces of Via Flaminia in line with the road you walked along were found during these excavations, as marked on the sketch map above.

Detour to San Feliciano di Mormonzone

This is sometimes taken to be the site ‘ad montem rotundum’ (at the round mountain) where St Felician died, which (according to his legend, BHL 2846) was three Roman miles from ‘his city’. As set out in more detail in the page on the complex, this is fine if one assumes that St Felician’s city was Forum Flaminii (some 6 km to the north). Unfortunately, as Paoloa Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 53) pointed out, although St Felician had been the bishop of Forum Flaminii, the legend generally reserves the phrase civitate sua for Fulginia (as in ‘civitatem suam Fulgineas’), which was much closer (whether it was near Santa Maria in Campis or at modern Foligno). In addition, as a glance around you will confirm, there is not a mountain in sight.

Retrace your steps to Santa Maria in Campis, where the detour ends

Archeological Area (again)

Roman Domus [18]

Guerrini and Latini: p. 264, entry 7

With the church of Santa Maria in Campis on your right, walk back towards Via Rubicone, and then take the lane on the left that follows the fence along the south side and west sides of the Archeological Area, as far as the covered excavation site on the right (illustrated above). Excavations here in 1969-72 unearthed the remains of a large Roman domus, which Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (as above) dated to the first half of the 1st century AD. It comprised seven rooms that opened onto a courtyard. Parts of the mosaic pavement from this building are exhibited in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci (Rooms 8 and 9).

Private Baths [19]

Guerrini and Latini: pp. 263-4, entry 6

A structure that was contiguous with, but distinct from, the domus above was apparently excavated in 1811. It was evidenced by the remains of mosaics in three rooms, the walls of which no longer survived. Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (as above) dated it to the early imperial period. The complex was apparently bounded to the west by a wall of polygonal travertine blocks that would have pre-dated it.

According to Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1984, at p. 467):

-

“... at that time [of the excavation], the excavators believed that the later remains should be attributed to a temple of the goddess Hebe, because a small bronze statuette that apparently portrayed her found here. [However] it seems more likely to be a private thermal complex, given limited extension of the structure and the recent discovery other privately owned buildings [as above] in the immediate vicinity” (my translation)

The statuette identified as that of Hebe has been lost.

-

“Believed by some to be nearly contemporary with the sculpture by Lysippos, this statuette may date from the beginning of the Roman Empire (first century AD).”

In/ near Piazza del Risorgimento

Piazza del Risorgimento during excavations

(Photograph from Museo Archeologico)

Turn left and then right intoVia Costantini and then immediately left into Piazza del Risorgimento, which is at the centre of a 1960s housing development.

Finds from Piazza del Risorgimento [17]

Guerrini and Latini: p. 274, entry 26

Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below) described the excavations that were carried out here in 1998. They centred on a stretch of Roman road, some 4 meters wide, that crossed the piazza diagonally, directed towards the putative theatre and amphitheatre mentioned above. Objects found in a canal beside the road (exhibited in the Sala Gotica of the Museo Archeologico, Palazo Trinci) included fragments of black-glazed pottery that could be dated to the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC.

A wall along the north side of the road contained an entrance that gave access to a burial ground that was in use in the 1st century BC and 1st century AD.

-

✴2o tombs (8 inhumation graves, and 12 that contained cremated bodies), which dated to the 1st century BC and early 1st century AD, were excavated along the north side of the road. Another inhumation tomb and a funerary tower were found to slightly to the north. The associated grave goods are described by Matelda Albinesi (referenced below, 2012). In tomb 12, which was the largest and which dated to the early 1st century AD, there were signs of the fire used for cremation and an interesting collection of grave goods that included bone fragments from a funerary bed.

-

✴Two small votive bronze (ca. 500 BC) were also found during the excavations, one in the form of a warrior's helmet and another in the form of a shield (both exhibited in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci). This suggests that there was an ancient sanctuary nearby (see the mention of what was probably an associated Umbrian necropolis in Via Po, above).

These excavations provoked a rethink about the likely pattern of residential occupation of the area:

-

✴Matelda Albanesi (referenced below, 2005-6, at p. 290) pointed out that the results made it difficult to detect here the ‘usual’ Roman model of a concentrated urban area surrounded by necropoles. She suggested (at p. 291) that:

-

“The data available [from these excavations] rather support the thesis of a ‘non-concentrated urbanisation’ as suspected by older sources” (my translation).

-

The source that she cited in this context was Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1984, at p. 478), who suggested that the fact that the triumvir Octavian was able to confine an opposing army at “the stronghold of Fulginia” during the Perusine War indicated that:

-

“... the settlement here had walls, at least until 40 BC ... [However], Silius Italicus, a poet living in the 2nd century AD, described Fulginia as an unwalled city in the plain ..., which seems to allude to a ‘non-concentrated urbanisation’, as is also suggested by the archeological record of the [area here in the] imperial period” (my translation).

-

✴Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below, 2012, at p. 21) offered a different interpretation of these data:

-

“The discovery of the funerary area of Piazza Risorgimento [16], and thus of an area that must have been extra-urban, only a few hundred meters from the Archeological Area of Santa Maria in Campis [11, 13, 18, 19, 20], where the Roman city was located, illustrates how the centre of Fulginia had a very circumscribed urban development, ... limited at the margins by two funerary areas: at the southeast, of the huge necropolis excavated near the church of Santa Maria in Campis [24]; and, to the west, the funerary area of Piazza Risorgimento” (my translation).

-

In other words, on this model, the urban area of the putative Roman city here was very concentrated indeed!

C0in Hoard [16]

Samuele Ranucci [b] and [c], both referenced below

In situ Restored coins displayed in Museo Archeologico

During these excavations of Piazza del Risorgimento, a hoard of over 3,000 silver denarii that had been buried in a leather sack was found near thegraves to the north of the Roman road. These coins covered a time span from the 3rd to the 1st century BC. Some of the coins are exhibited in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci (Sala Gotica).

RRC 523/1a: C·CAESAR·III·VIR·R·P·C/ Q·SALVIVS·IMP·COS·DESIG

The most recent of the coins in the hoard (RRC 523/1a) had been minted in the name of Octavian and his general, Quintus Salvidienus Rufus, who was identified as consul-designate. In fact, Salvidienus had been nominates as one of the consuls for 39 BC but he was subsequently accused of treachery against Octavian and died (either by suicide or execution) before he could take up his office. Thus this coin must date to 40 BC. Since Salvidienus played a central role in the siege of Perusia in 41-40 BC, Samuele Ranucci [c] (referenced below, at p. 89) observed that:

-

“It seems probable that the coins had been minted by the besiegers of Perusia for the [payment of the] legions engaged in the war effort ...” (my translation).

Foligno had, in fact, been caught up in the war in early 40 BC when Octavian’s general, Agrippa, had confined an army here that had mustered in order to attempt to raise the siege. Samuele Ranucci [c] (referenced below, at p. 87) suggested that the hiding of this hoard and the one from site 15 (below) was probably directly related to these events.

The museum commentary indicates that, in 40 BC, the value of the coins in this hoard would have been been somewhat in excess of the amount that a single legionary would have earned during his entire career. Samuele Ranucci [b] (referenced below, at p. 26) pointed out that there is no secure basis on which to determine what the precise reasons for the hiding of this fortune might have been:

-

“One can, of course, speculate, imagining, for example, that we are dealing with the savings of a high-ranking officer or the valuable loot of a thief, rather than the treasury of an army, buried in a hurry. Alternatively, as is probably preferable, we could leave the explanation to the imagination of each individual” (my translation).

We can also only speculate on the reason why the unfortunate owner of the coins never recovered them.

C0in Hoard [15]

Samuele Ranucci [a], referenced below

Restored coins displayed in Museo Archeologico

Cross the piazza to the right and continue along Via Vitelli, to the junction with Via Trasimeno. The second hoard of Roman silver coins mentioned above was discovered here in 1962. 156 coins survive, and these might well represent the totality of the original hoard. A selection of the restored coins is exhibited in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci (Sala Gotica), together with what seems to be a fragment of the ceramic container in which they were apparently buried.

These coins covered a time span from the 3rd to the 1st century BC. The most recent of these coins (RRC 511/3a) was minted in Sicily by Sextus Pompeius and dated to 42-40 BC. One wonders whether this hoard and the one discussed above had been buried by the same unfortunate owner.

Area of the Railway Station

Roman Residential Insula [22]

Guerrini and Latini: p. 265 entry 9

Turn left along Via Trasimeno and right at the end to follow Via Santa Maria in Campis. This road turns sharply left at the T-junction, with the railway line on your right. A Roman residential insula was discovered here in 1890 during work associated with the building of the railway. According to Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1984, at pp. 469-70) the structure had a rigidly geometric articulation and comprised at least three separate residences He deduced from a water-colour representation of a mosaic from a fourth areaof the complex (illustrated as his figure 6) that it dated to the late 1st century BC or the early 1st century AD. Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (as above) dated the complex to the imperial period.

Burials [8]

Guerrini and Latini: p. 271 entry 19

Evidence for a small number of burials from the imperial period were discovered in 1963 between platforms 4 and 5 of the railway station during the construction of an underpass. [Cinerary urn(s) in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci ??]

End of the Walk

Take the underpass on the left to walk under the railway line and continue along Via Santa Maria in Campis (with the massive military barracks on your right) to Viale Roma. The rest of this walk, along Viale Roma to Porta Romana, is described in Walk III.

Read more:

G. Galli (Ed.), “Foligno, Città Romana: Ricerche Storico, Urbanistico e Topografiche sull' Antica Città di Fulginia”, (2015) Foligno, which includes:

✴G. Galli, “Foligno Città Romana: Considerazioni sugli Studi Topografici e sulle Emergenze Archeologiche”, pp. 35-74

✴P. Camerieri, “Il Castrum e la Pertica di Fulginia in Destra Tinia”, pp. 75-108

M. Albanesi, “Indagini a Santa Maria in Campis di Foligno: una Fase Tardoantica a Fulginia”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 37 (2014) 559-66

P. Guerrini and F. Latini, “Foligno: Dal Municipium Romano alla Civitas Medievale: Archeologia e Storia di una Città Umbra”, (2012) Spoleto

M. L. Manca and S. Ranucci (Eds.), “I Tessoretti Romani di Foligno”, (2012) Perugia, which includes:

✴M. L. Manca, “Foligno Archeologica”, pp. 7-10

✴S. Ranucci [a], “Tesoretto Rinvenuto nel 1962”, pp. 11-16

✴M. Romana Picuti, M. Albanesi and S. Ranucci, “Tesoretto Rinvenuto nel 1998”, pp. 17-26:

•M. Romana Picuti, “Lo Scavo”, pp 19-21

•M. Albanesi , “I Corredi delle Tombe”, p. 22

•S. Ranucci [b], “Il Ripostiglio Monetale da Piazza Risorgimento”, pp. 23-6

S. Ranucci [c], “Il Ripostiglio di Denari Romani Repubblicani da Piazza Risorgimento a Foligno: Reliqua Pars”, Annali dell’Istituto Italiano di Numismatica, 58 (2012) pp. 79-137

L. Sensi (Ed.), “Discorso di Fabio Pontano sopra l’ Antichità della Città di Foligno”, (2008)

M. Albanesi, “La Necropoli Romana di Santa Maria in Campis a Foligno: Ultime Scoperte”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 29-30 (2005-6) 289-306

L. Bonomi Ponzi, “Inquadramento Storico-Topografico del Territorio di Foligno”, in:

M. Bergamini (Ed.), “Foligno: La Necropoli Romana di Santa Maria in Campis”, (1988) Perugia, pp. 11-18

L. Sensi, “Fulginia: Appunti di Topografia Storica”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 8 (1984) 463-92

L. Sensi, “Un Sarcofago Paleocristiano da Santa María in Campis”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 6 (1982) 19-34

History of Fulginia: From Conquest to Municipalisation After Municipalisation

Location of Roman Fulginia Roman Walk I Roman Walk II Roman Walk III

Return to Walk III

Return to History of Foligno