Adapted from Giovanni Mengozzi, “De' Plestini Umbri del loro Lago e

della Battaglia Appresso di Questo Seguita tra i Romani e i Cartaginesi”, (1781)

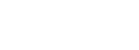

The upland plateau at modern Colfiorito, some 25 km east of Foligno, forms an important pass across the Apennines that has been in use at least from the early Iron Age. A number of ancient roads converged here, including two important ones from the Valle Umbra that came to be known as:

-

✴Via della Spina, from modern Spoleto;

-

✴Via Plestina, from modern Foligno.

Having converged, these roads continued to the site of modern Camerino, from whence a route through a syncline valley led north to connect with the series of river valleys that provided routes to the Adriatic coast.

Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below, at p. 45) observed that:

-

“... the discovery of grave goods from the 6th century BC that had been imported from both Etruria and Greece in the necropolis of Colfiorito [see below] ... is indicative of the dual direction of trade, involving both the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian regions” (my translation).

As we shall see, these important lines of communication shaped the early history of the region.

The Plestini

Habitation of the Upland Plain

Unsurprisingly, given its excellent lines of communication, the plain of Colfiorito was inhabited from a an early date. Traces of oval wooden huts that were in use in the 10th-7th centuries have been excavated at three separate locations:

-

✴at località la Capannaccia, the later site of the sanctuary of Cupra (see below);

-

✴on the later site of the Roman city, in part under the Roman domus opposite the church of Santa Maria di Plestia (see below); and

-

✴at località Fonte Formaccia (some 500 meters from Santa Maria di Plestia, along the road to Taverne).

Hilltop Settlements

Monte Orve and the plateau of Colfiorito

Image courtesy of Dottoressa Maria Roman Picuti

A line of some 50 hill forts has been identified on the ridge to the southwest of the lake. It seems that the people moved from the shores of the lake to these higher settlements in the late 7th century BC, perhaps because the plain had become subject to inundations.

Monte Orve

The most important of these hilltop centres was on Monte Orve, to the west. It took the form of a settlement on artificial terraces with a sanctuary above. The surrounding circuit of walls of some 1,300 meters, which was built using polygonal stones, dates to ca. 400 BC. Excavations carried out in 2001-8 on the southern slopes of the settlement revealed objects that attest to the continuing use of the site at least until the 3rd century BC. The sanctuary continued in use thereafter, and received a temenos wall in ca. 100 BC. Other finds made during these excavations included a marble fragment that probably came from a cult statue (1st century AD).

Necropoles

Necropolis of Colfiorito

Some 248 tombs have been discovered since 1962 in the necropolis that served these centres of habitation, between the foot of Monte Orve and the modern cemetery of Colfiorito. As Laura Bonomi Ponzi (“L B P”, referenced below) reported, the tombs belonged to four chronological phases:

-

✴37 graves (9th - 7th centuries BC) probably belonged to people from the lake-side villages (“L B P”, pp. 35-58). The grave goods found inside them (which were similar to those from the contemporary Acciaierie Necropolis, Terni) suggest a non-stratified society that buried its dead with impasto grave goods of local manufacture. Grave goods from this phase that were found in the late 19th and early 20th centuries entered the Bellucci Collection.

-

✴20 graves (7th and 6th centuries BC) contained more varied grave goods, including iron and bronze objects and wheel-made impasto pottery, again predominantly of local manufacture (“L B P”, pp. 59-80).

-

✴125 graves (6th - 4th centuries BC) represented the community in its prime. These included a small number that contained prestige grave goods (bronze fragments of pieces of armour and from ceremonial chariots as well as items used in banqueting) indicative of an aristocracy that had forged trading links with the neighbouring regions on both sides of the Apennines (“L B P”, pp. 81-134). Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below, at p. 42) associated this phase of use with the settlement of Monte Orve discussed above.

-

✴The remaining 66 graves (late 4th and 3rd centuries BC) betray the influence of Rome after the conquest (“L B P”, pp. 135-8).

Grave goods from all four phases of use of this necropolis are exhibited in the Museo Archeologico di Colfiorito, and other grave goods from Phase 1 (including some from Tomb 8) are exhibited in the Museo Archeologico, Perugia.

Necropolis of Annifo di Foligno

The remains of a princely tomb were found in 1984 at Annifo di Foligno, northwest of modern Colfiorito. The tomb, which dates to the middle of the 4th century BC, had already been destroyed, but it still contained part of an iron wheel from a chariot and rich tableware for banqueting. The goods were similar to those found in the warrior tombs from the 3rd phase of the Colfiorito necropolis. The surviving grave goods are in the Museo Archeologico di Colfiorito.

Sanctuary of Cupra before the Roman Conquest

Present church of Santa Maria di Plestia, near Colfiorito

Excavations carried out in 1962-7 at località la Capannaccia, some 200 meters north of the church of Santa Maria di Plestia, (both marked on the map above) revealed the existence of an important Umbrian sanctuary that had been in use from the 6th to the 1st century BC.

Votive Bronzes (6th - 4th centuries BC)

The Museo Archeologico, Colfiorito exhibits a large number of votive bronzes that attest to the vibrant cult activity at the sanctuary from the 6th century BC until the Roman conquest. Other votive bronzes from this period are exhibited in the Museo Archeologico, Perugia and in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci, Foligno.

Bronze plaques (4th century BC)

cupr]as, matres pletinas sacru esu

Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Umbria (MANU), Perugia

cupr [ cupr]as, matresp[letinas

MANU, Perugia MAC, Colfiorito

cupras, matres pletinas sacru

Museo Archeologico di Colfiorito (MAC), Colfiorito

The most important finds were four fragmentary bronze plaques with inscriptions relating to the presiding deity, Cupra:

-

✴two of which are exhibited in the Museo Archeologico, Perugia; and

-

✴two of which are in Museo Archeologico, Colfiorito;

are inscribed in the Umbrian language using an Etruscan alphabet that shows the influence of Volsinii (Orvieto). None of the inscriptions is complete, but they can be reconstructed to read:

cupras, matres pletinas, sacru esu

I am a sacred to Cupra, mother of the Plestini

All four are illustrated on the site of the Associazione Culturale Istituto di Ricerche e Documentazione sugli Antichi Umbri, Gubbio.

Roman Conquest

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

The Umbrians made their first significant entry into recorded history in 308 BC when, according to Livy (‘Roman History’, 9:41), they assembled at Mevania (modern Bevagna) intent upon attacking Rome, a initiative that led to their ignominious defeat. The composition of this Umbrian alliance is unknown, but it certainly did not include Ocriculum (modern Otricoli), on the southern border of Umbria, which received a foedus (bilateral treaty with Rome) in the immediate aftermath of the engagement, and this status was also conferred on Camerinum at about this time.

In 299 BC, the Romans took the Umbrian city of Nequinum by force and founded the Latin colony of Narnia on the site. This was a period of growing tension, on the eve of the Third Samnite War (298-90 BC). According to Livy:

-

“The report of a Gallic tumult [in 299 BC], in addition to a war in Etruria, had caused serious apprehensions at Rome; and, with the less hesitation on that account, the Romans concluded an alliance with the state of [Picenum]”, (‘History of Rome’, 10: 10: 12).

In parallel, an anti-Roman alliance formed between the Saminites, the Gallic tribes of northern Italy (including the Senones, who occupied the territory north of Picenum) and undefined ‘Etruscans’ and ‘Umbrians’. The decisive battle of the Third Samnite War, which was also decisive for the Roman conquest of Umbria and Etruria, was fought in 295 BC near the later site of the municipium of Sentinum (modern Sassoferrato) some 60 km north of Plestia. The Roman base during the battle was even closer, at Camerinum. Although the Romans took heavy casualties, including the death of one of the consuls, they emerged victorious. We have no evidence that the Plestini played any significant part in these events but, given their proximity to Camerinum and Picenum, we might reasonably assume that they were unlikely to have engaged in any anti-Roman activity. The Romans had probably arrived at Camerinum by the route shown in green above, which included the Via della Spina from Spoletium to Plestia.

The period after the Third Samnite War saw the Romans consolidate their control of the area surrounding Plestia:

-

✴According to Florus:

-

“During the [first] consulship of Manius Curius Dentatus [i.e. in 290 BC], the Romans laid waste with fire and sword all the [Sabine lands]. By this conquest, so large a population and so vast a territory was reduced, that even [Curius] could not tell which was of greater importance”, (‘Epitome of Roman History’, 1: 10).

-

✴According to Polybius:

-

“In a pitched battle [in 283 BC], the army of the Senones was cut to pieces [by an army led by Manius Curius Dentatus]. The rest of the tribe was expelled from the country, into which the Romans sent the first colony that they ever planted in Gaul: namely, ... Sena [Gallica], so called from the tribe of Gauls that had formerly occupied it”, (‘Histories’, 2: 19).

-

✴According to Florus:

-

“Then [i.e. in 268 BC] all Italy enjoyed peace , ... except that the Romans thought fit themselves to punish those who had been the allies of their enemies. The people of Picenum were therefore subdued and their capital Asculum was taken under the leadership of Sempronius [Sophus] ...”, (‘Epitome of Roman History’, 1: 14: 19).

Finally, in 241 BC, as the Romans emerged victorious from the First Punic War, they founded the Latin colony of Spoletium (in circumstances that are undocumented in the surviving sources).

The most fateful of these events for the Plestini would have been the foundation of the citizen colony of Sena Gallica in 283 BC, in what was, by then, the Roman ager Gallicus: the site that was chosen for it was at the mouth of the Misa river, which was easily reached from Sentinum by an ancient road that ran the length of the valley. There is evidence that this colonial settlement was accompanied by viritane settlement on the newly-conquered territory, a development that was further stimulated by the agrarian law that was sponsored in 232 BC by the tribune Caius Flaminius. We can therefore reasonably assume that the road links marked in green on the map above became increasingly important as the century progressed.

Via Flaminia (220 BC)

Green = Via Flaminia, according to surviving itineraries

Red = road from Forum Flaminii to Sena Gallica via Camerinum after 220 BC

Underline in blue = assigned to the Oufentina tribe (dotted blue = possible assignation)

Adapted from Federico Uncini (referenced below, at p. 22)

The patterns of traffic between Rome and the Adriatic were transformed in 220 BC, when the censor Caius Flaminius (the tribune of 232 BC and consul of 223 and 217 BC) built Via Flaminia. After leaving Rome, this road entered Umbria at Ocriculum and continued to Narnia, where it split into two branches:

-

✴one branch passed through Spoletium; and

-

✴the other through Mevania,

These two branches converged at Forum Flaminii. It terminated at Ariminum (modern Rimini), a Latin colony that had been founded in 268 BC on the what was, at that time, border between Roman and Gallic territory. We know that Via Flaminia entered Umbria at Ocriculum from its inception and that Ariminum was its original destination. Furthermore, as discussed below, Flaminius probably established Forum Flaminii at the time that he constructed the road.

Thus, we can be reasonably certain of the route of Via Flaminia from Rome to Forum Flaminii (albeit that there is some doubt about whether one branch was built before the other):

-

✴Most scholars believe that, from its inception, it took the route from Forum Flaminii to Ariminum that is marked in green on the map above, which involved crossing the Apennines by the Scheggia pass (Aesis) and the Gola del Furlo (Intercisa).

-

✴However, in a series of publications in 1959-81, Gerhard Radke argued that it originally:

-

•followed the old Via Plestina from Forum Flaminii to Plestia;

-

•continued via Camerinum and Sentinum to Sena Gallica; and

-

•turned north along the coast to Ariminum.

-

✴It is certainly possible that a direct route to both colonies would have been preferred in 220 BC, particularly if it avoided the difficult Gola del Furlo. However, as is clear from the map above, there were a number of other possible routes that would have met these criteria:

-

•some via Plestia and Camerinum (including the route proposed by Radke); and

-

•some using one of the other Apennine passes, from Nuceria, Helvillum or Aesis.

We have no evidence for which of these possible routes was used before ca. 27 BC, when the ‘green’ route first appeared in a surviving itinerary.

It is possible that some light can be thrown on this puzzle by considering the pattern of Roman settlement in the area:

-

✴In the ager Gallicus, most of the viritane settlers in the decades after the conquest (including those who had settled here in 232 BC under the auspices of Caius Flaminius) had been assigned to the Pollia tribe, an ancient voting tribe that had been extended for the first time in 283 BC for the citizen colonists at Sena Gallica.

-

✴In Picenum, the the citizens who were settled here after the conquest seem to have retained their original voting tribes until 241 BC, when (like those in the erstwhile territory of the Praetutti to the south of them) they had been assigned to the newly-established Velina tribe.

-

✴There is no reason to think that there was widespread viritane settlement of this kind in Umbria in the 3rd century BC. However, Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 217) suggested that there might have been:

-

“... a further settlement initiative associated with Caius Flaminius in coincidence with the opening of Via Flaminia in 220 BC .... [For example,] the constitution of [Forum Flaminii], which was certainly accompanied by viritane settlement and patently linked to the opening of the road ... , might indicate that [this putative settlement programme] was linked to the extension into Umbria of the Oufentina [which was certainly the tribe of Forum Flaminii]” (my translation).

Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at pp. 91-2) observed that:

-

“Forum Flaminii. which was presumably founded by Caius Flaminius on his great road , was in the Oufentina, which was also made the tribe of neighbouring Plestia.”

The evidence for Plestia is provided by two inscriptions (both discussed further below):

-

✴an inscription (CIL XI 5621) from the early imperial period commemorates an octovir who had been assigned to this tribe; and

-

✴a later inscription (CIL XI 5619) commemorates a quattuorvir who was also assigned to this tribe.

These inscriptions both relate to the situation after the municipalisation of Plestia: however, as discussed below, there is evidence for viritane settlement in the territory of the Plestini at an earlier date, and the eventual tribal assignation of Plestia might well reflect the original assignation of these earlier citizen settlers.

The Oufentina had been established in 318 BC for Roman citizens who were settled on land that had been confiscated from Privernum, and was subsequently assigned to other settlers in this vicinity. Lily Ross Taylor indicated (in her entry for the Oufentina on p. 273) that the assignations at Forum Flaminii and Plestia represented the only extension of the Oufentina to a new geographical location before the Social War. She observed (at p. 306) that:

-

“It is possible that the Oufentina ... was the tribe of Flaminius, ... But it is also possible that ... [this assignation] represented an attempt on the part of Flaminius to gain [political support] in certain tribes by adding to them men who would be under obligation to him.”

Of course, now that the Via Flaminia existed, such obligated men would find it relatively easy to travel to Rome in order to vote.

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 224) suggested that the putative settlement programme promoted by Caius Flaminius in 220 BC might have included the territories of the other centre in Umbria that were (or were possibly) assigned to the Oufentina after the Social War: Nuceria; Pitinum Pisaurense; Trebiae and Tuficum. However, the evidence that the first three of these centres were assigned to the Oufentina is not conclusive:

-

✴The evidence for Nuceria comes from four inscriptions (CIL XI 5553, 1st century BC; EDR028715, (10 BC - 10 AD); CIL XI 5539, Augustan; CIL XI 5382, ca.80 AD); from neighbouring Asisium. Asisium was certainly assigned to the Sergia so this concentration of inscriptions related to men from the Oufentina is odd. However, there is no reason to believe that any or all of them came from Nuceria, except that it is the only nearby centre for which the tribal assignation is otherwise unattested.

-

✴Only two inscriptions from Pitinum Pisaurense indicate its possible tribal assignation:

-

•AE 1959, 0094 commemorated ‘C(aius) Planius C(aius) f(ilius) Of(entina) Priscus’, who had held a number of civic posts up to that of quatuorvir iure dicundo; and

-

•CIL XI 6033 honoured ‘C(aius) Caesidio C(aius) f(ilius) Cru(stumina) Dexter’, who was a priest and patron of the municipium.

-

Simona Antolini and Silvia Marengo (referenced below, at p. 214) settled for ‘Oufentina ?’

-

✴Three inscriptions from Trebiae suggest different assignations, with nothing to choose between them: CIL XI 5005 (Aemilia); CIL XI 5013 (Sergia); and CIL XI 5012 (Oufentina).

However, the evidence that Tuficum was assigned to the Oufentina is very strong: see, for example, Simona Antolini and Silvia Marengo (referenced below, at p. 213).

In short, I think that it is at least possible that Caius Flaminius arranged for viritane settlement in the vicinity of the later municipia of Plestia and Tuficum in 220 BC because they were both (like Forum Flaminii) on the route of the original Via Flaminia. As far as I know, there is no supporting evidence for viritane settlement at Tuficum at this time. However, Guy Bradley (referenced below, at pp. 141-2) observed that the coming of the Roman period led to a dramatic change to the dispersed pattern of habitation that had previously characterised the territory of the Plestini:

-

“It is tempting to connect the [end of the use of the earlier] cemeteries and perhaps of the fortified centres to which they related with the establishment of [the Roman settlement] of Plestia on the shores of the lake here in the (? early) 3rd century BC. ... [In the surrounding area,] the farms of the Roman era seem to be ‘typologically homogeneous’, as would be expected from viritane settlement.”

Second Punic War (218 - 201 BC)

Hypothetical location of the Lacus Umber

After Carlo Pietrangeli, ‘Mevania’, (1953) Rome

Via Flaminia is indicated here in red, on the assumption that both branches existed at this time

In 217 BC, Hannibal famously crossed the Alps and inflicted a series of defeats on the Romans. The most devastating occurred at Lake Trasimene, about 100 km west of Plestia (with Perusia roughly halfway between them). Caius Flaminius, the builder of Via Flaminia in 220 BC and now the Roman general opposing Hannibal, was killed during this battle. It is possible that the next time that Hannibal defeated a Roman army, the engagement took place in the territory of the Plestini, although (as we shall see) the surviving sources are confusing on this point.

What we do know is that another disaster followed in the wake of Flaminius’ defeat: according to Polybius:

-

“About the same time as the battle of [Trasimene, the other] consul Gnaeus Servilius, who had been stationed on duty at Ariminium, ... having heard that Hannibal had entered Etruria ... sent Gaius Centenius forward in haste with 4,000 horse ... But Hannibal, getting early intelligence of this [belated attempted] reinforcement of the enemy after the battle of [Trasimene], sent Maharbal with his light-armed troops and a detachment of cavalry. Maharbal, falling in with [Centenius], killed nearly half his men at the first encounter; and having pursued the remainder to a certain hill, took them all prisoner on the very next day. The news of the battle of [Trasimene] was only three days' old at Rome, and the sorrow caused by it was, so to speak, at its hottest, when this further disaster was announced” (‘Histories’, 3: 86).

Livy gave a similar account:

-

“[Soon after the defeat at Trasimene] ... another unexpected defeat was reported [at Rome]: 4,000 horse, which had been sent under the command of [Gaius] Centenius, propraetor, by the consul Cnaeus Servilius [to reinforce Flaminius] were cut off by Hannibal in Umbria, to which place, on hearing of the battle at [Trasimene], they had turned their course” (‘History of Rome’, 22:8).

Unlike Polybius, Livy did not record the place from which Servilius had sent Centenius, and he gave the victory over the latter to Hannibal himself, rather than to Maharbal. He added the important detail that this victory had occurred in Umbria.

Appian was more specific (although not necessarily more accurate) about these events. He had Servilius based on the Po rather than at Ariminum as Hannibal approached, while Centenius was living as a private citizen in Rome:

-

“The greater part [of the Roman army] was dispatched against Hannibal under [the consuls] Gnaeus Servilius and Gaius Flaminius ... Servilius hastened to the Po ... [and] Flaminius ... guarded Italy within the Apennines .... Thus had the Romans divided their large armies ... Hannibal, learning this fact, moved secretly in the early spring, devastated Etruria, and advanced toward Rome. The citizens became greatly alarmed as he drew near, for they had no force at hand fit for battle. Nevertheless, 8,000 of those who remained were brought together, over whom Centenius, one of the patricians, although a private citizen, was appointed commander, there being no regular officer present, and sent into Umbria to the Plestine marshes to occupy the narrow passages which offered the shortest way to Rome” (‘War against Hannibal’, 9).

He also gave an account of the battle:

-

“When Hannibal saw the Plestine marsh and the mountain overhanging it, with Centenius between them guarding the passage, he ... sent a body of lightly armed troops under the command of Maharbal to ... pass around the mountain by night. When he judged that [these troops] had reached their destination, he attacked Centenius in front. ... The Romans, thus surrounded, took to flight, and there was a great slaughter among them: 3,000 being killed and 800 taken prisoners, while the remainder escaped only with difficulty”, (‘War against Hannibal’, 11).

It is difficult to see how Appian’s account could make topographical sense, since the Lacus Plestinus (the later site of Plestia, marked at the upper right in the sketch map above) did not block Hannibal’s route from Trasimene to Rome. As Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 285) observed:

-

“.. for various reasons, it seems unlikely that the [second] catastrophe occurred precisely at the lake of Plestia: the time interval for Maharbal to get from Trasimene to Plestia and for the news to be carried to Rome will not fit Polybius’ indication... Most scholars therefore discount Plestia and put the disaster of Centenius further westwards, in the direction of Perusia.”

Guy Bradley (referenced below, at p. 148) also pointed out that some scholars think that Appian had confused the Lacus Plestinus with the Lacus Umber. Bradley himself was unconvinced, but it does seem to me to be more likely that Centenius had occupied the passage along the shore of the Lacus Umber in order to prevent Hannibal reaching Via Flaminia. However, as Ronald Syme (as above) observed, even if Appian’s account was inaccurate in important respects, he had:

-

“... preserved a valuable geographical detail. Though prone to all manner of error and confusion, he need not be accused of ‘inventing’ the lake of Plestia. The very oddity of the detail inspires a certain confidence.. How the story came to include the lake baffles conjecture. Perhaps Centenius had marched [from Rome] not by the Flaminia but by the Camerinum road.”

Of course, if my speculation above is correct, Vi Flaminia might have been the ‘Camerinum road’.

Plestia

The church of Santa Mari di Plestia stands on the foundations of a public building with a colonnaded front, which was probably the “basilica forense” (basilica of the forum) of the Roman municipium of Plestia. Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below at p. 50) observed that:

-

“In the absence of extensive excavations, the actual extension of [Plestia] and its urban plan are both unknown: perhaps the inhabited nucleus was not particularly extensive and, as in analogous cases elsewhere in the Apennines, it was made up of only public buildings, while the population continued to live in nearby villages, a legacy of the previous Umbrian period” (my translation).

Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 285) observed that:

-

“The only record of [Plestia] in all ancient literature is in Pliny’s list of Umbrian communities [see below]. But the name survives as ‘Pistia’ [as in Santa Maria di Pistia or di Plestia], and inscriptions confirm the localisation.”

The reference here is to Pliny the Elder, who placed the Plestini among the communities of the Augustan Sixth Region (‘Natural History’, 3:19).

The surviving archeological evidence for Plestia in the Republican period largely relates to the continued use of the sanctuary of Cupra at a Capannaccia

Sanctuary of Cupra after the Conquest

Terracotta Reliefs from the Sanctuary (3rd - 1st centuries BC)

The Museo Archeologico, Colfiorito displays a number of terracotta reliefs that would have decorated the exterior of the sanctuary and attest to its monumentalisation after the Roman conquest. (The notes in the museum record that they belonged to three separate phases:

-

✴antefixes from the late 3rd century BC;

-

✴decorative reliefs, some depicting chariot races, from the middle of the 2nd century BC; and

-

✴reliefs suggesting a restoration of the exterior in the early 1st century BC.

Other antefixes from this period are exhibited in the Museo Archeologico, Perugia and in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci, Foligno.

Votive Objects from the Sanctuary (3rd century BC)

The local displays a number of votive objects (3rd century BC) from the sanctuary, most of which are made from terracotta and depict body parts, which attest to the change in cult practices after the Roman conquest.

Coins from the Sanctuary (3rd century BC)

This display in the museum of other objects that were found during the excavations of the sanctuary include coins (at the lower right) from Neapolis (Naples) and Ariminum (Rimini) that date to the 3rd century BC.

Latin Graffiti (3rd - 1st centuries BC)

The museum exhibits a number of bucchero fragments inscribed in Latin that were found during the excavation of the sanctuary, which indicate that it continued in use into the late Republic. Two of these fragments, which date to the period 225 - 150 BC, possibly record the names of a husband and wife:

-

✴P̣(ublius) Apiaie .../ us (EDR 159466); and

-

✴[A]piaiea (EDR 159512).

Archeological Evidence from Plestia

Excavations on a site opposite the church have brought to light a large domus (ca. 30 BC) with mosaic floors and frescoed walls (which was probably on the opposite side of the forum). Although this complex is essentially configured as a private home with an entrance hall and other rooms around two colonnaded courtyards, its unusually large size (ca. 2200 square meters) suggests that it more probably accommodated the municipal authorities. Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2014, at pp. 195-6) has discussed this building in the context of the similar domus publicae that have been excavated at Tadinum and at Suasa in the ager Gallicus. He characterised all three urban centres as:

-

“... cities without [private] houses: ...[each of which] evidently functioned [as the administrative centre] of a population that was thinly spread across the territory [of the municipium]” (my translation).

A rectangular room next to the domus had a portico facing the forum, contained a pit for the remains of sacrificial animals, and was perhaps used for the cult of the Lares Pubici (deities who protected the municipality.

Administrative Structure of Plestia

This topic is discussed in detail in my page on Octoviri and Quattuorviri at Plestia.

Octovirate

CIL XI 5621 AE 1991, 646

The presence of octoviri at Plestia is known from two funerary inscriptions that were recorded in Santa Maria di Plestia, both of which are now in the Museo Archeologico di Colfiorito:

-

✴CIL XI 5621 commemorates Titus Liconius, the son of Titus Liconius Serapione and Arnila Secunda, who is recorded as:

-

T(ito) Liconio T(iti) f(ilio) Ouf(entina) VIIIvir(o)

-

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 143, citing Eugen Bormann, CIL XI p. 812) dated the inscription to the early Augustan period (i.e. ca. 27 BC). (The EDR database - see the CIL link - gives a much later date, but I wonder if that is a mistake). This is also the earliest known reference to the tribal assignation of Plestia to the Oufentina tribe (discussed above).

-

✴AE 1991, 646 commemorates:

-

M(arcus) Annio, T(iti) l(iberto)/ VIIIvir(o) ch...

-

The dating of this inscription is uncertain:

-

•Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 143) dated it to the Republican period (i.e. before 27 BC);

-

•the EDR database (see the AE link) dated it to the period 30 BC - 30 AD; and

-

•the museum similarly dated to the late 1st century BC or early 1st century AD.

Marcus Annius is explicitly described as a freedman, and the cognomen of Titus Liconius Serapione, the father of the other octovir above, suggests that the second octovir, although freeborn (as evidenced by his filiation), was the son of a freedman. As discussed in my page on Octoviri and Quattuorviri at Plestia, most scholars think that they were municipal magistrates, although it seems to me that this octovirate was a non-decurial college.

Quattuorvirate

According to Simone Sisani (referenced below, at p. 143):

-

“‘... the primitive constitution of the municipality of the Plestini [whatever it was]... only adjusted at a later date to that of the nearby municipia, with the introduction of quattuorviri” (my translation)

This magistracy is recorded at Plestia in a now-lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5619) that was recorded in the crypt of Santa Maria di Plestia. It had been erected by Caius Allieius Martialis to commemorate his son, Caius Allieius, who was recorded as:

[C(aio) Alli]eio C(ai) f(ilio) Ouf(entina)/ ae[d(ili?)] IIIIvir(o) quaest(ori)

The cursus here seems to be in the wrong order, but Caius Allieius had apparently held the posts of quattuorvir, aedile and quaestor. The EDR database (see the CIL link) dates the inscription to the period 50-200 AD.

Simone Sisani (referenced below, at p. 273) suggested that the quattuorvirate had been introduced at Plestia in the early Augustan period (ca. 27 BC), as evidenced by the development of the city:

-

“... the first significant building [at Plestia, including the construction of the putative domus publica] does not seem to have taken place before the early Augustan period. This development constituted the prerequisite for the elevation of the centre to the status of a municipium, which would have taken place concurrently with the adoption of the canonical quattuorviral constitution” (my translation).

However, this model is based on the assumption (discussed above) that the octovirate evidenced at Plestia in the late 1st century BC and the early 1st century AD indicates the administrative structure of the centre prior to a late municipalisation. However, as discussed above, these octoviri might have had non-administrative (perhaps priestly) functions, then we have no basis on which to establish when the quattuorvirate was established at Plestia: the ‘default’ assumption would be that this occurred immediately after the Social War.

Later Roman Period

Inscribed Tile (1st century AD)

R(es) P(ublica) P(lestinorum)

(I have picked out the letters in black to make them legible). This provides evidence for a furnace for the production of tiles, owned by the municipium of Plestia.

Titus Lavvius Gratus

A funerary inscription (CIL XI 5620) that was recorded in the crypt of Santa Maria di Plestia (which is apparently in the deposit of the Soprintendenza Archeologia dell' Umbria) commemorates Tuenda, a freed slave of a lady called Gavia. It was erected by her husband, Titus Lavvius Gratus, who is recorded as:

T(ito) Lauvio Grato / VIvir(o) Aug(ustali)

The EDR database (see the CIL link) dates the inscription to the period 50-200 AD.

Caius Veianius Rufus (late 2nd century AD)

An inscription (CIL XI 5635) from Camerinum, which is now now in the sala maggiore of the Municipio there, commemorated Caius Veianius Rufus, who came from Camerinum and became a prominent figure there. Among his many public offices, he was appointed as ‘curator rei publicae Plestinorum’ by two Antonine emperors, probably Marcus Aurelius and Commodus, who were joint Augustii in the period 177-80 AD.

Two Imperial Inscriptions (late 2nd century AD)

These fragmentary two inscriptions probably came from Santa Maria di Plestia:

-

✴The first of these, which is now in the Museo Archeologico Colfiorito, reads:

-

[I]MP(eratori) CAE(sari)

-

[di]VI ANTO[nini filio)

-

[di]VI Hadr[riani nipoti];

-

which could refer to Marcus Aurelius (161-80 AD) or Lucius Verrus (161-9 AD).

-

-

-

✴The second (CIL XI 5618), which was documented in the church but was subsequently lost, was inscribed:

-

[D]ivo / [Com]modo

-

and probably commemorated the deified Emperor Commodus (180-92 AD).

This reference to the deified status of Commodus has an interesting back story: the Senate declared him a public enemy (tantamount to a damnatio memoriae) after his assassination in 192 AD, but the Emperor Septimius Severus rescinded this in the following year and deified him. Septimius Severus then “adopted” Commodus’ father, Marcus Aurelius, as his own, and described himself as “divi Commodi frater” (brother of the deified Commodus). It is tempting to infer from this that the first inscription honoured the deified Marcus Aurelius (rather than Lucius Verus), and that the two dedications were made shortly after 193 AD.

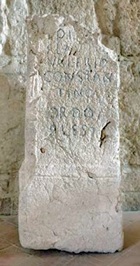

Divus Constantinus (ca. 337 AD)

Di[vo]/ Flavio/ Valerio/ Constan/tino Aug(usto)

ordo/ Ples(tinorum)

It records that the council of Plestia had dedicated something to the deified Emperor Constantine. Angela Amici (referenced below, at p. 199) suggested that the presence of Constantine’s full name here probably indicates that the inscription slightly pre-dates his death, with the epithet divus applied later.

Giorgio Bonamente (referenced below, search on ‘Spello’) observed:

-

“[This inscription] has a markedly public nature, since it was promoted by the ordo Plestinorum. [It was found] ... near the town of Spello, where a temple for the worship of the gens Flavia had been established, with the permission of Constantine [in the Rescript known from the inscription, CIL XI 5265]. When they [apparently] implemented the decree of the Senate which proclaimed the consecration of Constantine, the people of Plestia were certainly aware of the close connection that existed between the site and the annual celebrations in Spello ..., which was the most important political event throughout Umbria at this time” (my translation).

This temple at Spello must have become the main locus for veneration of divus Constantinus in the area after 337 AD, although its relationship to the cult site at Plestia is unclear.

[Could the cippus originally have been been set up in the temple at Hispellum by the Ordo of Plestia, and subsequently returned, perhaps when the temple at Hispellum became a Christian church ??]

[In construction from here]

Roman drainage channel was discovered in 1997 at località Fonte delle Mattinate (about 5 km northeast of Colfiorito on SS 77, towards Serravalle del Chienti) during repairs of the nearby Renaissance drainage system known as the Botte dei Varano (which had been damaged in the earthquake of that year). The Roman structure, which extends for about 1 km, was constructed using large travertine blocks. It was probably built in the late 1st century BC in order to protect Plestia from flooding, and it remained in use until the 6th century AD. (The Botte del Varano was built in the 15th century and, following the repairs of 1997, remains in use).

Florentius, Episcopus Ecclesiae Plestanae/ Plestinae attended the synods Pope Symmachus convened in Rome in 499 and 502 (see the lists published by Giovanni Domenico Mansi, referenced below, Volume 8: pp. 235 for 499; and p. 269 for 502).

Read more:

R. Syme (author, who died in 1989) and F. Santangelo (who edited these papers from the Ronald Syme archive), “Approaching the Roman Revolution: Papers on Republican History”, (2016) Oxford

S. Sisani, “Città Senza Case: la Domus come Spazio Pubblico nei Municipia dell’ Umbria”, in:

S. Gutiérrez e I. Grau (Eds.), “De la Estructura Doméstica al Espacio Social: Lecturas Arqueológicas del Uso Social del Espacio (Atti Alicante 2012)”, (2014) Alicante, pp. 191-206

G. Bonamente, “Costantino fra Divinizzazione e Santificazione.: Una Sepoltura Contestata”, Enciclopedia Costantiniana (2013)

S. Antolini and S.Marengo, “Regio V (Picenum) e Versante Adriatico della Regio VI (Umbria)”, in

M. Silvestrini (Ed.), “Le Tribù Romane: Atti della XVIe Rencontre sur l’Epigraphie du Monde Romaine (Bari, 8-10 Ottobre 2009)”, (2010) Bari, at pp. 209-15

M. Romana Picuti, "Plestia e la Valtopina: Prima e Dopo il 295 avanti Cristo”, in:

F. Bettona and M. Romana Picuti (Eds), “ La Montagna di Foligno: Itinerari tra Flaminia e Lauretana”, (2007) Spello, pp. 39-55

S. Sisani, “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

F. Uncini, “La Viabilità Antica nella Valle del Cesano”, (2004) Monte Porzio

A. Amici, “Divus Constantinus: le Testimonianze Epigrafiche”, Rivista Storica dell' Antichità, 30 (2000) 187–216

G. Bradley, "Ancient Umbria", (2000) Oxford

L. Bonomi Ponzi, "La Necropoli Plestina di Colfiorito di Foligno", (1997) Perugia

L. Ross Taylor, “The Voting Districts of the Roman Republic: The 35 Urban and Rural Tribes”, (1960) Rome

G. Mansi, “Sacrorum Conciliorum Nova et Amplissima Collectio Origina”, (1758-98) Venice and Florence

Plestia: Main Page Octoviri at Plestia Municpalisation of Plestia

History of Fulginia: From Conquest to Municipalisation After Municipalisation

Location of Roman Fulginia Roman Walk I Roman Walk II Roman Walk III

Return to History of Foligno