Forum Flaminii and Via Flaminia

Forum Flaminii, which was probably located at modern San Giovanni Profiamma, some 6 km north of Foligno, almost certainly owed its existence to the building of the Via Flaminia (below). The evidence for this is as follows:

-

✴Festus presented “Forum Flaminium” (and “Forum Julium”) as examples of:

-

“... fora named for the men who established them, which were used to buy and sell goods ... on roads and in fields” (‘De verborum significatu quae supersunt cum Pauli epitome’, my translation); and

-

✴Strabo described Forum Flaminii as one of the settlements on Via Flaminia that had been:

-

“... filled up with people on account of the [road] itself, rather than [as a consequence] of political organisation” (‘Geography’, 5: 2:10).

This prompted Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 295), for example, to assert that:

-

“As for Forum Flaminii, its origins are patent: [it was] a settlement established when [Via Flaminia] was built, on territory taken from Fulginia. ... .”

As we shall see, this is over-confident:

-

✴the tribal assignation of Forum Flaminii does suggest (but does not prove) that it was established at the time that the road was built (as discussed below); and

-

✴there is no surviving evidence of any kind that relates to the previous ownership of the site.

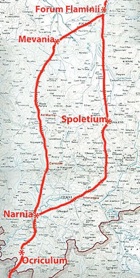

Via Flaminia (220 BC)

-

✴one branch passed through Spoletium (Spoleto); and

-

✴the other through Mevania (Bevagna).

These the two branches probably converged at or near Forum Flaminii (as discussed below), before continuing across the Apennines to Rimini (Ariminum) on the Adriatic coast.

There is some doubt about the precise date at which Via Flaminia was built:

-

✴Festus recorded that it was named for Caius Flaminius:

-

“The Circus Flaminius and the Via Flaminia are named for the consul Flaminius, who was killed by Hannibal [in 217 BC] beside the Lake of Trasimene” (‘De verborum significatu quae supersunt cum Pauli epitome’, my translation).

-

This is sometimes taken to imply that Flaminius built the road when he was consul, a post that he held for the first time, in 223 BC. However, it seems more likely that Festus was simply using the consulship to identify Flaminius as the general who was killed at Lake Trasimene (during his 2nd consulship).

-

✴Livy was more specific about the date of the road: according to the Periochae (summary) of Book 20 of his ‘History of Rome’, Flaminius built it in 220 BC, when he held the post of censor.

I have assumed that Livy’s information is correct.

There is also doubt about whether both branches in Umbria formed part of the original project. I discuss the various arguments in my main page on Via Flaminia. In summary:

-

✴The earliest surviving reference to Via Flaminia is by Strabo in the work first published in 7 BC mentioned above:.

-

"The cities ... on the Flaminian Way itself [are]:

-

•Ocricli [Otricoli], near the Tiber;

-

•Narnia [Narni], through which the Nar River flows (it meets the Tiber a little above Ocricli, and is navigable, though only for small boats);

-

•Carsuli; and

-

•Mevania [Bevagna], past which flows the Teneas (this too brings the products of the plain down to the Tiber on rather small boats);

-

... [together with] other settlements [on this road], which have become filled up with people rather on account of the Way itself than of political organisation; these are:

-

•Forum Flaminium [Forum Flaminii]; and

-

•Nuceria [Nocera Umbra] (the place where the wooden utensils are made) …

-

Secondly, to the right of the Way, as you travel from Ocricli to Ariminum [Rimini], are:

-

•Interamna [Terni];

-

•Spoletium [Spoleto]; and

-

•Aesium [Assisi] …

-

On the other side of the Way:

-

•Ameria [Amelia];

-

•Tuder [Todi] (a well-fortified city);

-

•Hispellum [Spello]; and

-

•Iguvium [Gubbio], the last-named lying near the passes that lead over the mountain” (‘Geography’, 5: 2:10).

-

This account describes the places on the western branch (Carsulae and Bevagna) as “on the Flaminian Way, while places on the eastern branch (Terni and Spoleto) are located “to the right of the Way”.

-

✴In fact, the eastern branch is only documented from the 3rd century AD, most scholars therefore assume that only the western branch formed part of Flaminius’ project (see, for example, Ronald Syme, referenced below, at p. 287 and Paolo Camerieri, referenced below, at p. 37 et seq.).

-

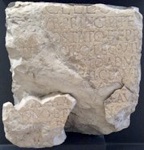

✴However, as Simone Sisani (referenced below, at p. 124-5) pointed out, the earliest of these itineraries (that of Strabo) dated to ca. 7 BC, some 200 years after the road’s construction. He argued that Flaminius’ road had more probably originally followed the eastern route, through the important Roman colony at Spoletium. He cited evidence for this from an Umbrian inscription that uses the Latin alphabet (ST UM 6, 220 - 200 BC), which was found at San Pietro di Flamignano, on the eastern branch of Via Flaminia, between modern Sant’ Eraclio and Trevi: this inscription records the construction of bia (fountain) and names of two marones (magistrates) that was, in all probability, associated with the opening of this branch of the road.

It is also surely important to bear in mind that Emperor Augustus had restored Via Flaminia in 27 BC, twenty years before Strabo’s account. Augustus’ intervention clearly involved the western branch: for example, he built the bridge at Narnia that is named for him, which took the road over the Nera and on to Mevania. Slightly further along this branch of the road, an important side road connected it to Hispellum (Spello), a colony that Augustus had established in 40 BC and provided with a circuit of walls at the time of his restoration of Via Flaminia. More importantly still, he had built a magnificent pan-municipal sanctuary below these new walls. It is at least possible his restoration of Via Flaminia had privileged its western branch and that this accounts for the emphasis that the subsequent itineraries gave to it.

In short, the absence of hard evidence to the contrary, I think that we must assume that both branches of the road both formed part of the original project.

Forum Flaminii in the Surviving Itineraries

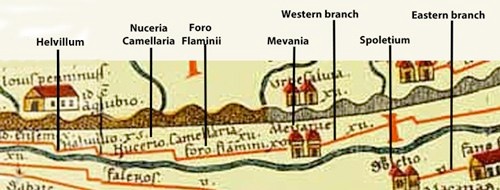

Detail from the Tabula Peutingeriana (Biblioteca Augustana der Fachhochschule, Augsburg)

It is usually assumed that Forum Flaminii was located at the point at which the two branches of Via Flaminia converged before crossing the Apennines. However, the relevant documentary sources are confusing in this respect. Strabo (7 BC, quoted above) only described the western branch, on which he placed Forum Flaminii. However, Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, at p. 51) pointed out that:

-

“... the [other surviving] itineraries .. never mention Forum Flaminii when describing the western branch of the Flaminia, except in the case of the Tabula Peutingeriana [the original of which probably dates to ca. 300 AD]: but this gives a patently inaccurate distance between Mevania and Forum Flaminii of 16 (rather than the actual 7.5) Roman miles” (my translation).

In the other three surviving itineraries:

-

✴the itinerarium Gaditanum (which is inscribed on the four so-called Vicarello Cups that date to roughly the 1st century AD) only describes the eastern branch and does not mention Forum Flaminii at all;

-

✴the Itinerarium Antoninum (ca. 300 AD) places “Foro Flamini vicus” on the eastern branch, 18 Roman miles after Spoletium and 27 Roman miles before Helvillum (which is placed on both branches, suggesting that they converged here rather than at Forum Flaminii); and

-

✴the Itinerarium Hierosolymitanum (333 AD), which only describes the eastern branch, includes “ciuitas foro flaminii” 20 Roman miles after Spoletium.

Despite all this confusion, reconstructions of the route based on surviving evidence does indicate a convergence at San Giovanni Profiamma, the presumed site of Forum Flaminii: see, for example, Paolo Camerieri, referenced below:

-

✴at p. 50 for the approach from Bevagna on the western branch; and

-

✴at pp. 70-2 for the approach from Sant’ Eraclio and Santa Maria in Campis (to the east of modern Foligno) on the eastern branch.

Original Status of Forum Flaminii

Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at pp. 91-2) observed that:

-

“Forum Flaminii. which was presumably founded by C. Flaminius on his great road [in ca. 220 BC], was in the Oufentina [tribe], which was also made the tribe of neighbouring Plestia.”

The surviving inscriptions that indicate this assignation for Forum Flaminiii include the following two inscriptions:

-

✴A funerary inscription (AE 1911, 0013) from Africa Proconsularis commemorates:

-

L(ucius) Liberius L(uci) f(ilius)/ O(u)fentina Foro Fla/minii Iulianus

-

who had died when only eight months old, after his family had moved from Forum Flaminii to Carthage.

-

✴A funerary stele, which Emanuela Biagetti (referenced below) discovered in a rural location about halfway (as the crow flies) between San Giovanni Profiamma and Spello i n 1978, commemorates:

-

L(ucius) Pompullius L(uci) f(ilius) Ouf(entina)

-

Maxsimus(!) ann(orum) XIX

-

Biagetti dated it, tentatively, to the 2nd century AD, while Luigi Sensi (referenced below, at p. 16, number 17) dated it to the late 1st century BC or the early 1st century AD.

Thus, the proof of this tribal assignation is unusually strong. Lily Ross Taylor (referenced below, at p. 306) suggested that:

-

“It is possible that the Oufentina ... was the tribe of Flaminius, ... But it is also possible that ... [this assignation] represented an attempt on the part of Flaminius to gain [political support] in certain tribes by adding to them men who would be under obligation to him.”

Of course, now that the Via Flaminia existed, such obligated men would find it relatively easy to travel to Rome in order to vote.

Simone Sisani (referenced below, at p. 217) was of a similar opinion. He noted that two other centres on Via Flaminia, Nuceria (Nocera) and Trebiae (Trevi), had possibly been assigned to the Oufentina (although the evidence for this is not conclusive), adding that:

-

“The inclusion among these centres of Forum Flaminii - the foundation of which, certainly accompanied by viritane settlement, was clearly linked to the opening of Via Flaminia in 220 BC - strongly suggests that the introduction of the Oufentina into Umbria was the initiative of Flaminius” (my translation).

Simone Sisani (as above) pointed out that, as tribune of the plebs in 232 BC, Flaminius had passed a plebiscite that provided for the division of the the ager Gallicus (on the Adriatic coast) for new settlements that were assigned to the Pollia tribe. However, he also pointed out pointed out that other centres - Plestia, near Forum Flaminni, and Pitinum Pisaurense (further north along Via Flaminia towards the Adriatic) - were both assigned to the Oufentina rather than the Pollia, and suggested that this was further evidence of a second phase of colonisation under the auspices of Caius Flaminius, in association with the opening of Via Flaminia in 220 BC.

It is important to stress that there is no hard evidence for either the previous ownership of the land that was used for this putative viritane settlement or for the precise legal status of Forum Flaminii thereafter.

Second Punic War (218 - 201 BC)

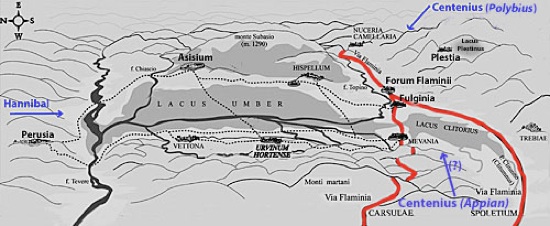

Hypothetical location of the Lacus Umber

After Carlo Pietrangeli, ‘Mevania’, (1953) Rome

Via Flaminia is indicated here in red, on the assumption that both branches existed at this time

In 217 BC, Hannibal famously crossed the Alps and inflicted a series of defeats on the Romans. The most devastating occurred at Lake Trasimene, some 25 km northwest of modern Perugia. As mentioned above, Caius Flaminius, the builder of Via Flaminia in 220 BC and now the Roman general opposing Hannibal, was killed during this battle.

Another disaster followed in the wake of Flaminius’ defeat: according to Polybius:

-

“About the same time as the battle of [Trasimene, the other] consul Gnaeus Servilius, who had been stationed on duty at Ariminium, ... having heard that Hannibal had entered Etruria and was encamped near Flaminius, designed to join the latter with his whole army. But finding himself hampered by the difficulty of transporting so heavy a force, he sent Gaius Centenius forward in haste with 4,000 horse, intending that he should be there before himself in case of need. But Hannibal, getting early intelligence of this reinforcement of the enemy after the battle of [Trasimene], sent Maharbal with his light-armed troops and a detachment of cavalry. Maharbal, falling in with [Centenius], killed nearly half his men at the first encounter; and having pursued the remainder to a certain hill, took them all prisoner on the very next day. The news of the battle of [Trasimene] was only three days' old at Rome, and the sorrow caused by it was, so to speak, at its hottest, when this further disaster was announced” (‘Histories’, 3: 86).

Livy gave a similar account:

-

“[Soon after the defeat at Trasimene] ... another unexpected defeat was reported [at Rome]: 4,000 horse, which had been sent under the command of [Gaius] Centenius, propraetor, by the consul Cnaeus Servilius [to reinforce Flaminius] were cut off by Hannibal in Umbria, to which place, on hearing of the battle at [Trasimene], they had turned their course” (‘History of Rome’, 22:8).

Unlike Polybius, Livy did not record the place from which Servilius had sent Centenius, and he gave the victory over the latter to Hannibal himself, rather than to Maharbal. He added the important detail that this victory had occurred in Umbria.

Appian was more specific (although not necessarily more accurate) about these events. He had Servilius based on the Po rather than at Ariminum as Hannibal approached, while Centenius was living as a private citizen in Rome:

-

“The greater part [of the Roman army] was dispatched against Hannibal under [the consuls] Gnaeus Servilius and Gaius Flaminius ... Servilius hastened to the Po ... [and] Flaminius, with 30,000 foot and 3,000 horse, guarded Italy within the Apennines .... Thus had the Romans divided their large armies ... Hannibal, learning this fact, moved secretly in the early spring, devastated Etruria, and advanced toward Rome. The citizens became greatly alarmed as he drew near, for they had no force at hand fit for battle. Nevertheless, 8,000 of those who remained were brought together, over whom Centenius, one of the patricians, although a private citizen, was appointed commander, there being no regular officer present, and were sent into Umbria to the Plestine marshes to occupy the narrow passages which offered the shortest way to Rome ” (‘War against Hannibal’, 9).

He also gave an account of the battle:

-

“When Hannibal saw the Plestine marsh and the mountain overhanging it, with Centenius between them guarding the passage, he ... sent a body of lightly armed troops under the command of Maharbal to explore the district and pass around the mountain by night. When he judged that [these troops] had reached their destination, he attacked Centenius in front. ... The Romans, thus surrounded, took to flight, and there was a great slaughter among them: 3,000 being killed and 800 taken prisoners, while the remainder escaped only with difficulty” (‘War against Hannibal’, 11).

It is difficult to see how Appian’s account could make topographical sense, since the Lacus Plestinus (the later site of Plestia, marked at the upper right in the sketch map above) did not block Hannibal’s route from Trasimene to Rome. As Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 285) observed:

-

“.. for various reasons, it seems unlikely that the [second] catastrophe occurred precisely at the lake of Plestia: the time interval for Maharbal to get from Trasimene to Plestia and for the news to be carried to Rome will not fit Polybius’ indication... Most scholars therefore discount Plestia and put the disaster of Centenius further westwards, in the direction of Perusia.”

Guy Bradley (referenced below, at p. 148) also pointed out that some scholars think that Appian had confused the Lacus Plestinus with the Lacus Umber. Bradley himself was unconvinced, and Nereo Alfieri (referenced below, a paper that I have not been able to access) argued that the Lacus Plestinus should be retained as the location of the battle. However, it does seem to me to be more likely that Centenius had occupied the passage along the shore of the Lacus Umber in order to prevent Hannibal reaching Via Flaminia. Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 125) argued that, having defeated Centenius, Hannibal probably marched along the eastern branch of Via Flaminia in order to reach Spoleto. On this basis, and assuming that the Lacus Umber was in roughly the place suggested in the sketch map above, Centenius‘ defeat probably took place on its eastern shore, perhaps below the later hilltop site of Asisium (Assisi).

According to Livy, immediately after these victories:

-

“Hannibal, marching directly through Umbria, arrived at Spoletium, having completely devastated the adjoining country, and commenced an assault upon the city” (‘History of Rome’, 22:9).

Polybius apparently had a different source for the sequence of events at this time:

-

“Feeling now entirely confident of success, Hannibal rejected the idea of approaching Rome for the present; but traversed the country plundering it without resistance, and directing his march towards the coast of the Adriatic. Having passed through Umbria and Picenum, he came upon the coast after a ten days' march” (‘Histories’, 3: 86).

John Lazenby (referenced below, at p. 66) observed that:

-

“Although there is no direct conflict [between these two accounts] ..., a march from Lake Trasimene to the Adriatic via Spoletium [as reported by Livy] is well nigh impossible to reconcile with Polybius’ statement that Hannibal reached the sea [in only 10 days] ...”

Simone Sisani (referenced below, at p. 125) accepted Livy’s account, suggesting that Hannibal had probably marched along the eastern branch of Via Flaminia in order to reach Spoletium. John Lazenby took the opposite view, preferring Polybius’ account, which implies a much more direct march to the coast, although he conceded that Hannibal might still have sent a raiding party to Spoletium. What is important here is the fact that Hannibal probably marched to Forum Flaminii before:

-

✴continuing across the Apennines, having sent a raiding party to march along the eastern branch of Via Flaminia to Spoletium (Lazenby); or

-

✴taking this route himself with a view to continuing to Rome (Sisani).

On either scenario, it seems likely that both Forum Flaminii and the surrounding territory received the attentions of his army in the aftermath of its victory at Trasimene.

Forum Flaminii after the Social War (90 BC)

No epigraphic evidence survives to illuminate the fate of Forum Flaminii after the Social War (when most Italian cities were enfranchised and constituted as municipia administered by quattuorviri). However, the list by Pliny the Elder of the tribes of the Augustan Sixth Region’ (‘Natural History’, 3:19) following the Augustan reforms of ca. 7 BC included the ‘Fulginiates’ and the ‘Foroflaminienenses. This suggests that Fulginia and Forum Flaminii were separate municipia at that time.

The inscription commemorates Caius Ancharius Verus, who had died while still only 22 years old, having been a decurion in Fulginia and an aedile in Forum Flaminii:

C(aio) Anchario C(ai) f(ilio) Cor(nelia)/ Vero

dec(urioni) Fulg(iniae)

aed(ili) / F(oro) f(laminiensium)

This contains two important pieces of information:

-

✴Ancharius’ assignation to the Cornelia tribe, rather than the Oufentina of Forum Flaminii, suggests that he came from Fulginia, which must therefore have been assigned to the Cornelia.

-

✴Fulginia and Forum Flaminii still had separate administrations, albeit that a man from Fulginia could serve in the administration of Forum Flaminii.

(There was also a separate “splendidissimus ordo Foroflaminiensium” in the period 193-235 AD, as evidenced by CIL XI 5215-6, below.)

Finds from Forum Flaminii

Cesia Sabina

[CES]IAE C(AI) [FILIAE]

[S]ABINAE

[PA]RENTI MUNIC[IPII]

DEC(URIONUM) [DECRETO]

It is now in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci, with a label dating it to the 1st century AD.

Fountain

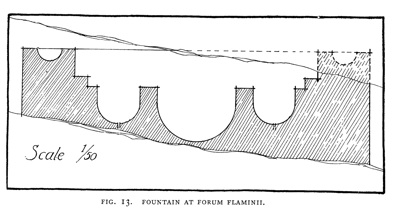

According to Thomas Ashby and Roland Fell (referenced below, at p. 177):

-

“In 1911, excavations on the right edge of the ancient road [as one travels towards the Adriatic] ... brought to light the remains of a fountain in concrete, faced with bricks and small rectangular blocks of stone. As we have seen no record of them, we give a plan of what was visible [as Figure 13, illustrated above].”

Unfortunately, the precise location of the fountain is no longer known.

Forum Flaminii under the Empire

Claudius Ptolemy (died ca. 168 AD) listed Forum Flaminii (along with Hispellum and Mevania, but omitting Fulginia) in his:

-

“Towns of the Umbri who are toward the east of the Tusci”, (‘Geography’, 3:1:47)

The Emperor Trebonianus Gallus and his son Volusianus were defeated by Marcus Aemilius Aemilianus in a battle near Interamna Nahars in 253 AD. They fled and were murdered by their own guards at Forum Flaminii.

The Emperors Valentinianus, Theodosius and Arcadius issued an edict (CTh.9.35.5) from “Foro Flamini” in the year of the consuls Timasius and Promotus (389 AD).

Inscriptions

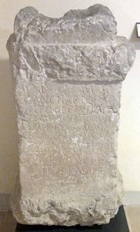

Publius Aelius Marcellus

CIL XI 5215 CIL XI 5216

These inscriptions (CIL XI 5215-6) are on the base of a statue found at San Giovanni Profiamma. It had been erected by the “splendidissimus ordo Foroflaminiensium” and commemorates Publius Aelius Marcellus, a member of the Papiria tribe. Since he is also commemorated in an inscriptions from the Roman province of Apulum (in modern Romania), which belonged to this tribe, it seems certain that this had been his place of birth. He served with distinction in three legions, including the II Gemina Pia Felix, which was given this title in ca. 197 AD.

It was probably thereafter that he embarked on a civic career: as decurion and patron of his native Apulum; and also as patron of the cities of Forum Flaminii, Fulginia and Iguvium (Gubbio). [What was his link to Umbria ??] The inscriptions, which the EAGLE database (see the CIL link) date to the period 193-235 AD, are now in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci.

Cnaeus Pompullius Hister

This funerary inscription (CIL XI 5246) [Date ??] from San Giovanni Profiamma reads:

CN(aei) POMPULLI T(iti) f(ilii) / COR(nelia) HISTRI

It is now in the Museo Archeologico, Palazzo Trinci.

Read more:

R. Syme (author, who died in 1989) and F. Santangelo (who edited these papers from the Ronald Syme archive), “Approaching the Roman Revolution: Papers on Republican History”, (2016) Oxford

S. Sisani, “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

G. Bradley, "Ancient Umbria", (2000) Oxford

P. Camerieri, “Il Tracciato della Via Flaminia”, in

I. Pineschi (Ed), “L’ Antica Via Flaminia in Umbria”, (1997) Rome

L. Sensi, “Nuovi Testi Epigrafici de Età Romana da Spello”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 11 (1987) 7-38

N. Alfieri, “La Battaglia del Lago Plestino", Picus, 6 (1986) 7-22

E. Biagetti and G. Forni, "Stele Funeraria e Autonomia Municipale di Forum Flaminii", Bollettino della Deputazione di Storia Patria per l' Umbria, 79 (1982) 13-17

J. F. Lazenby, “Hannibal's War: A Military History of the Second Punic War”, (1978) Warminster

L. Ross Taylor, “The Voting Districts of the Roman Republic: The 35 Urban and Rural Tribes”, (1960) Rome

T. Ashby and R. A. L. Fell, “The Via Flaminia”, Journal of Roman Studies, 11 (1921) 125-90

History of Fulginia: From Conquest to Municipalisation After Municipalisation

Location of Roman Fulginia Roman Walk I Roman Walk II Roman Walk III

Return to History of Foligno