Kings of Anshan and Susa (2100-2000 BC)

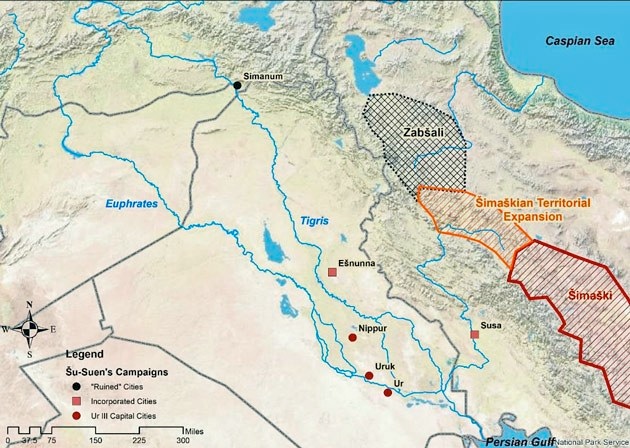

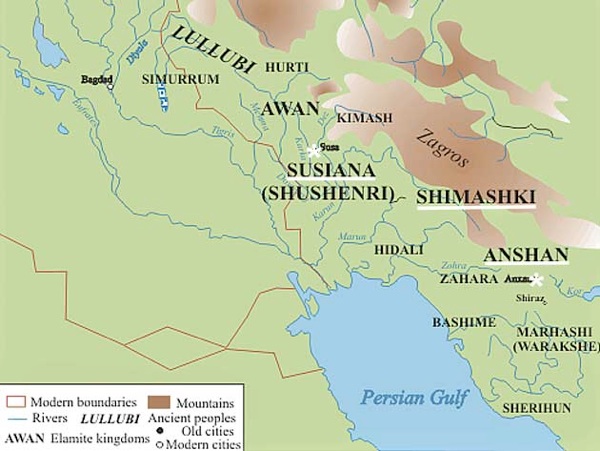

Map of Mesoptamia and Elam (from Wikipedia: red text = my additions)

As we have seen on the previous page, by ca. 2100 BC, Puzur-Inshushinak, the 12th and last king named in the Awan King List, had:

-

✴made Susa his capital and the ruler of Shimashki his vassals; and

-

✴subsequently taken control of land along the Diyala river to the north west, as far as Akkad (Sargon’s old capital, which was probably near modern Baghdad).

He had then adopted Sargonic titulary by:

-

✴identifying himself as the ‘mighty king of Awan’; and

-

✴naming one of his regnal years as ‘the year in which Inshushinak ... gave [me] the four quarters (of the world) to govern’.

As we shall see, he was driven out of Mesopotamia and then out of Susa by Ur-Namma, the founder of what we know as the Ur III dynasty.

Ur-Namma

Ur-Namma’ rise to power in Mesopotamia was recorded in the earliest-known recension of the so-called Sumerian King List (CDLI: P283804), which was almost certainly commissioned by Shulgi, his son and successor. However, this text simply recorded (in the formulaic manner that characterises the entire document) that, after Utu-Hegal had ruled at Uruk for 7 years, this city:

-

“... was struck down with weapons (and) the kingship was carried off to Ur. In Ur, Ur-Namma ruled for 18 years”, (col. vi, lines 13’-18;,transliteration at CDLI: P479895).

Although the actual circumstances in which Ur-Namma replaced Utu-hegal are unclear, we can reasonably rely on the information that his reign at Ur lasted for 18 years.

Ur-Namma and Puzur-Inshushinak

Unfortunately, we relatively little surviving evidence for Ur-Namma’s military campaigns. However, a royal inscription (RIME 3/2: 1: 1: 29), which is known from an Old Babylonian copy that was found in the Mesopotamian city of Isin, records that that:

-

“(I), Ur-Namma, mighty man, king of Ur, king of the lands of Sumer and Akkad, dedicated (this object) for my life. At that time, the god Enlil gave (?) ... to the Elamites. In the territory of highland Elam, they (Ur-Namma and the Elamites) drew up (lines) against one another for battle. Their (??) king, Puzur-Inshushinak, ... (the cities of) Awal, Kismar, Mashkan-sharrum, the lands of Eshnunna, the lands of Tuttub, the lands of Simudar, the lands of Akkad, all the people ...”, (RIME 3/2: 1: 1: 29, lines 11-23; see also the translation by Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 2008b, at p. 35).

Daniel Patterson (referenced below, at pp. 341-2) located Awal, Kismar and Mashkan-sharrum in the general vicinity of the confluence of the Tigris and Diyala rivers. Although it is not absolutely clear from the (now-lacunose) inscription, it seems that Ur-Namma claimed to have ‘liberated’ the territories listed here from Puzur-Inshushinak before confronting him in the Elamite highlands. The inclusion here of a reference to Ur-Namma’s liberation of ‘the lands of Akkad’ is interesting, particularly since, as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2019, at pp. 151-2) observed, Ur-Namma:

-

“... [revived] the Sargonic title of dannum (the mighty one) [= nita kalag-ga in Sumerian], ... [and] coined for himself a completely new title, which was ‘king of Sumer and Akkad’.”

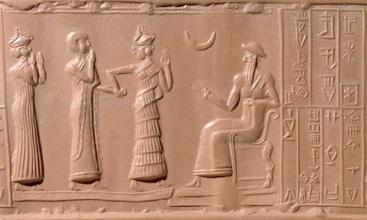

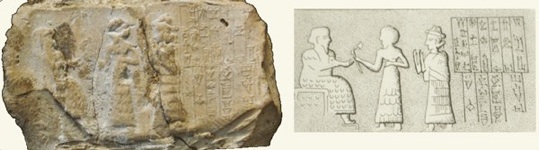

Seal of Hash-hamer, the governor of Ishkun-Sin in the reign of Ur-Namma

Now in the British Museum (BM 89126: image from the museum website

The inscription on the seal that made the modern image above is potentially relevant to this camapign of Ur-Namma: it reads:

-

“Ur-Namma, the mighty man, the king of Ur: Hash-hamer, ensi (governor) of Ishkun-Sin, your servant”, (RIME 3/2: 1: 1: 2001, see Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 1997, at pp. 88-9).

The image depicts the owner of the seal, Hash-hamer, between two goddesses, the first of whom leads him by the hand into the presence of Ur-Namma, who is seated on a throne. As Lorenzo Verderame (referenced below, at p. 66) observed, Ishkun-Sin, which does not appear in any of our surviving 3rd millennium sources, is mentioned in early 2nd millennium documents from Susa and Old Babylonian documents from Southern Mesopotamia. He observed that:

-

“If the Ishkun-Sin of these [later] documents and [that] of Hash-hamer’s seal are the same place, it must ;habve been] located east of the Tigris in an area of influence between Susa and southern Babylonia.”

He observed (at p. 69) that, if this is correct, then:

-

“... we can relate Hash-hamer’s seal to Ur-Namma’s expansion toward the Iranian plateau, culminating in the defeat of Puzur-Inšušinak and the conquest of Susa. In this scenario, Hash-hamer could be identified as

-

✴a local ruler who [either] supported Ur-Namma’s campaign against Susa or eventually submitted to [him]; or

-

✴a governor settled in a newly established province in the eastern region that would disappear during Shulgi’s and his successors’ reigns.”

Ur-Namma and Anshan

The prologue to Ur-Namma’s law code has been translated as follows:

-

“At that time, by the might of Nanna, my lord, I liberated Akshak, Marad, Girkal, Kazallu and their settlements, as well as Usarum, which had been enslaved by Anshan”, (RIME 3/2: 1: 1: 20, CDLI, P432130, lines 117-34: see also Martha Roth, referenced below, at p. 16 and Piotr Michalowski, referenced below, at p. 185).

Daniel Patterson (referenced below, at p. 33) suggested that this mention of Ur-Namma’s:

-

“... freeing of cities in northern Babylonia from servitude to Anshan ... may be related to his conflict with Puzur-Inshushinak and his conquest of Susa [see below].”

Ur-Namma at Susa

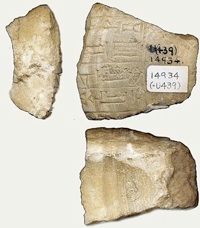

Three views of a fragment (CBS 14934) of a vase taken as booty from Susa to Ur by Ur-Namma

Image from the Penn Museum, where the fragment is now housed

Gianni Marchesi (referenced below) re-published the inscriptions on two ‘forgotten’ fragments of vases from Ur (CBS 14934 and CBS 14935, illustrated above) that are now in the Penn Museum, which indicated that the vases themselves had been taken as booty after a king of Ur had attacked Susa. He observed that:

-

“In previous scholarship, the capture of Susa was generally counted among the deeds of Shulgi, whom the majority of scholars considered to be the true builder of the Ur III empire.”

However, he was able to reconstruct the text of CBS 14934 (at p. 286) as follows:

-

“[To [a now-unknown deity], his lord/lady, Ur-Nammâ(k), ki]ng of Ur, [wh]en he smote [S]usa and [turned it into] booty [for this deity, presented (this vase to him/her) for his own life].”

Ur-Namma and the Shimashki

We know from a passage in an inscription of Puzur-Inshushiak (translated by Daniel Potts, referenced below, 2016, entry 1 in Table 4.12, at p. 113), after he had campaigned successfully against a number of centres including Kimash and Hurti (see the map below)

-

“... the king of Shimashki came to him, he (the unnamed king) grabbed his (Puzur-Inshushinak’s) feet; Inshushinak heard his prayers and ... ”.

There is no surviving evidence that Ur-Namma moved against either the Shimashki of Anshan after he had defeated Puzur-Inshushinak. Indeed, it seems that the unnamed king of Shimashki (or his successor) benefitted from Puzur-Inshushinak’s defeat and Ur-Namma’s lack of interest in the Elamite highlands:

-

✴as Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 125) observed:

-

“The destruction of Susa might have marked the end of the dynasty of Awan and the beginning of the dynasty of Shimashki in Elam”; and

-

✴as Katrien de Graef (referenced below 2022, at p. 444) similarly observed:

-

“... during the time of Ur’s rule in the Susiana plain, a new political power [emerged] in central Iran, [in the form of the] Shimashki ...”.

Shimaski King List

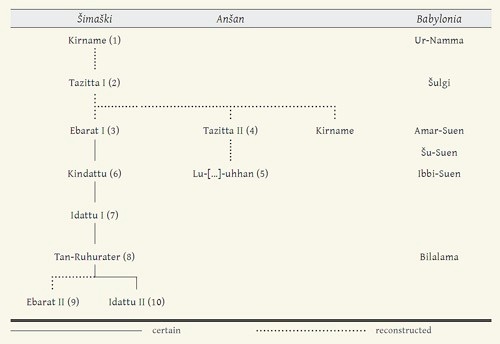

First 10 of the 12 ‘kings’ in the ShKL (from Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2014, at p. 290)

The numbers in brackets indicate the position of this king among to 12 in the list

The column on the right synchronises this list with the Ur III kings and Bilalama, the father-in-law of Tan-Ruhurater

Note that the direct genealogical link Ebarat I-Kindattu-Idattu is established by an inscription of Idattu (see below)

The so-called Shimashki King List (ShKL) is known from the reverse of what Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 2008a, at p. 38) characterised as:

-

“... a clay tablet from Susa, [now exhibit as Sb. 17729 in the Musée du Louvre], that can be dated on the basis of its script to the period ca. 1800-1600 BC.”

The so-called Awan King List (mentioned above in the context to Puzur-Inshushinak, the 12 and last name mentioned in it) was copied on the obverse of the same tablet. As Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 24) observed:

-

“The Shimashkian dynasty has been interpreted as the direct successor of the Awan dynasty that executed hegemony in larger Elam. Accordingly, Puzur-Inshushinak was more or less directly followed by Kirname (ShKL no. 1) ...”.

Since, as we have seen, at some time during his reign, Puzur-Inshushinak received the submission of a king of Shimashki, we might reasonably assume (with Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2014, at p. 289) that this was Kirname, and that he was subsequently able to benefit by Puzur-Inshushinak’s demise.

Early Kings of Shimashki

As we shall see, all of the following appear in Ur III administrative documents:

-

✴Ebarat, man of Shimashki, starting at Shulgi year 44 and continuing through the reigns of Amar-Sin and Shu-Sin;

-

✴Tazitta, man of Anshan, during the reigns of Amar-Sin and Shu-Sin; and

-

✴Kirname, man of Shimashki, during the reign of Shu-Sin.

Thus these three men must have been contemporaries, and this Ebarat can be securely identified as Ebarat I (ShKL 3). This means that, as reflected in the table above:

-

✴this ‘Tazitta, man of Anshan’ way well have been Tazitta II (ShKL 4), who was thus presumably a vassal of Ebarat I; but

-

✴this ‘Kirname , man of Shimashki’ could not have been named in the ShKL.

I will discuss Ebarat I and some other kings named in the ShKL in the relevant sections below. For the moment, we should merely note that, if we assume that the otherwise unknown Kirname (ShKL1) and Tazitta I (ShKL 2) were Ebarat’s immediate predecessors, then the period of their successive reigns must have overlapped to some extent with the successive reigns of Ur-Namma and Shulgi.

Shulgi

Shulgi at Susa

A B C

Objects from the reign of Shulgi found at Susa, now in the Musée du Louvre (images from the museum website)

A: foundation tablet (Sb. 2884) from Susa

B: foundation nail from Susa (Sb. 2881) from Susa

C: inscribed brick (A 6095) from Susa

The earliest indication of the presence of an Ur III king at Susa comes from surviving epigraphic evidence from the reign Shulgi. This evidence includes the Sumerian inscriptions on the objects illustrated above:

-

✴A: the text on this foundation tablet (Sb. 2884: RIME 3/2: 1: 2: 30; CDLI: P226994) from Susa reads:

-

“For the goddess Ninhursag of Susa, his lady: Shulgi, mighty man, king of Ur, king of the lands of Sumer and Akkad, built [this] temple for her.

-

✴B: the text on this foundation nail from Susa (Sb. 2881: RIME 3/2: 1: 2: 32; CDLI: P226991) reads:

-

“For the god Inshushnak, his lord: Shulgi, mighty man, king of Ur, king of the lands of Sumer and Akkad, built for him Arkesh, his beloved temple

-

✴C: the text stamped on this brick (A 6095: RIME 3/2: 1: 2: 31; IRS 2) from Susa reads:

-

“Shulgi, the strong man, king of Ur, king of Sumer and Akkad, has [re]built for Inshushinak his temple and restored it to its (original) place”.

Text

Shulgi’s Military Campaigns

Locations of Shulgi’s known military campaigns

(from Daniel Patterson, referenced below, Map 6, at p, 273: text in red = my addition)

Daniel Patterson (referenced below,at p. 35) observed that:

-

“Shulgi is often thought of as the king who structured the [Ur III] kingdom into the bureaucratic and administrative machine that seems to be reflected in the extant documentation. Characterised as a system of reforms, the relevant events seem to cluster around his 20th and 21st regnal years, [which separate]:

-

✴the earlier part of his reign, [which was] characterised by attention on infrastructure and cultic matters; from

-

✴the latter part of his reign, which was characterised by military affairs.

-

[These] ‘reforms’ include the deification of Shulgi [and] the creation of a standing army ... The last three decades of [his] rule are characterised ... by consistent military campaigning in regions to the east, southeast and northeast of the kingdom. These campaigns involved the establishment of garrisons in the peripheral territories which were subjected to taxes in livestock”

He also recorded (at pp. 50-1) the military campaigns that are recorded in ‘year names of Shulgi: these split into six periods, the first five of which can be summarised as followes:

-

✴The campaigns of years 24-6 were concentrated on Karahar and Simurrum.

-

✴The name of year 27 recorded the defeat of Harshi.

-

✴The campaigns of years 31-3 were again concentrated on Karahar and Simurrum.

-

✴The name of year year 34 recorded the defeat of Anshan (despite the fact that he had given his daughter in marriage of the ensi of Anshan in year 30 - see below);

-

✴The campaigns of years 42-5 involved Karahar and Simurrum again, together with Sharshrum, Urbilum and Lullubum further to the north.

It was only at this point that Shulgi turned his attention once more towards the Elamite highlands: as Daniel Patterson (referenced below, at p. 272) observed:

-

“... as he approach the end of his reign, [Shulgi’s] focus was diverted from the north to Hurti and Kimash ... .”

As he pointed out (at p. 193):

-

“This campaign is commemorated in the only military inscription securely attributed to Shulgi. It is a brick inscription [from an unknown location] written in Akkadian:

-

‘Shulgi, god of his land, the mighty, king of Ur, king of the four quarters: when he destroyed the land of Kimash and Hurti: he built [a moat and an embankment ??]’”, (RIME 3/2: 1: 2: 33; CDLI: P432197).

He also drew attention (at p. 191) to an earlier inscription of Puzur-Inshushinak from Susa, which started as follows:

-

“Puzur-Inshushinak, the ruler (ishshiak) of Susa, general (shakkanak) of the land of Elam, son of Shimpi-Ishhuk: when Kimash and Hurti became hostile to him, he went and captured his enemies ...”, (translated by Daniel Patterson, referenced below, at p. 191).

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 295) observed:

-

“... Shulgi’s victory over Kimash and Hurti was a reversal of Puzur-Inshushinak’s deed, in that, [while Puzur-Inshushinak’s victory had facilitated his march on northern Mesopotamia, Shulgi’s victory] opened up the Elamite highlands [to him].”

Shulgi, Anshan and Shimaski

The name given to Shulgi’s 30th regnal year was the year in which:

-

“The ensi of Anshan took the king's [i.e., Shulgi’s] daughter in marriage.”

However, it seems that this apparently benign situation did not last long: Shulgi’s 34th year was named as the year in which Anshan was destroyed, and the names of the next two years also referred to this event. Daniel Patterson (referenced below suggested:

-

✴at pp. 164-5, that the Anshanite ruler involved in these two events was probably Libum, an ensi of Anshan who is known from a tablet from Girsu date to Shulgi’s 33rd year (see CDLI, P128481); and

-

✴at p. 67, that, since another document from Girsu (see CDLI, P115919, col. 2, lines 7-10) that was dated to this year recorded payments made to workers who transferred the army:

-

•to Magan (on the west coast of the Persian Gulf, in what is now Oman) and

-

•from Anshan (which was easily reached for the nearby port of Liyan (modern Bushire, on the opposite side of the gulf);

-

this might well have been a maritime invasion that was completed within this year.

An administrative document from Puzr-Dagon (see CDLI: P123310, lines 10-12) recorded that, in Shulgi’s 44th year, he received a number of gifts of camels, including:

-

✴13 from Y-ab-ra-at, szimaszgi (Ebarat, the man of Shimashki) and

-

✴2 from Hu-un-da-hi-she-er, lu An-shanki (Hundahisher, the man of Anshan.

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2009, at p. 415) observed:

-

“... Yabrat of Shimaški, who ... can confidently be identified as Ebarat/Ebarti I, the third ruler [of the Shkl] ... [and] Hundah(i)sher of Anshan, ,, if not a king of Anshan himself, must have been an Anshanite official of considerable importance.”

Interestingly, the Shimashki are not mentioned in any of Shulgi’s year names. However, Daniel Patterson (referenced below, at p. 217):

-

✴referred to an administrative document (MVN 13, 672; CDLI: P117445) from the royal archives at Puzris-Dagan, which:

-

“... is dated to the first month of Shulgi’s 47th year, [and] mentions Shulgi’s son, Shu-Enlila, who received gifts on the occasion that he ‘ruined’ or ‘desecrated’ Shimashki”, (see obverse line 5 and reverse line 1); and

-

✴tabulated four more documents from Puzris-Dagan that dated to Shulgi’s 47th and 48th years , all of which related to plunder taken from Shimashki.

Amar-Sin

and Shu-Sin

Military Campaigns of Amar-Sin and Shu-Sin

Locations of Shu-Sin’s known military campaigns

(from Daniel Patterson, referenced below, Map 8, at p, 276: text in red = my addition)

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 196) observed, the reign of Amar-Sin, Shulgi’s successor:

-

“... represented the high point of the [Ur III] empire’s fortunes. [His] efforts concentrated mainly on political and economic consolidation, ... [and] there were no further [significant] attempts at territorial expansion.”

As we shall see, this period was followed in another of continuous decline that culminated in the catastrophic destruction of Ur, an event in which the Elamites played a decisive role. (discussed further below).

Gian Pietro Basello (referenced below, at p. 4/791) pointed out, 19 ‘dated’ administrative tablets from Susa that spanned some 24 years, from the 4th year of Amar-Sin to the 3rd year of Ibbi-Sin.

Mirko Surdi (referenced below) discussed the inscriptions on two bricks (IRS 1 = Sb 14724 and Sb 14725) from Susa (now in the Musée du Louvre) that had previously been attributed to Naram-Sin (the grandson of Sargon). However, he concluded (at pp. 2-3) that:

“[These] two alleged bricks of Naram-Sin ... should instead be ascribed to Shu-Sin [see below], whose name was written at the beginning of the inscription, now completely lost.”

This evidence of the continuous Ur III occupation of Susa in this period is complemented by the inscriptions on 14 bricks of Shu-Sin:

-

✴IRS 1 (2 bricks, mentioned above), with the titles ‘mighty king, king of Ur and of the four quarters’; and

-

✴IRS 3 (12 bricks), with the titles ‘beloved of Enlil, mighty king, king of Ur and of the four quarters’.

However, as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 196) observed, during the Shu-Sin’s reign:

-

“... the process of decline had set in, with the Babylonian rule over the periphery having been challenged on several fronts. In Iran, the most serious challenge came from a group of Shimashkian principalities, which formed an anti- Ur coalition led by the land of [Shimashkian] Zabshali.”

The severity of this threat is illustrated by the fact that the only one of the 9 year names of Shu-Sin records a military engagement, and that was with the Zabshali:

-

“Shu-Sin, the king of Ur, king of the four quarters, destroyed the land of Zabshali", (‘year names of Shu-Sin’, 7b).

I discuss this war further in the context of the reign of Ebarat I at Susa.

Ibbi-Sin

Year 5: married to daughter of ensi of Zabshali

Dynasty of the Shimashki

Ebarat I (3)

Seal of unknown provenance attributed to Ebarat I and modern impression

(now in the Gulbenkian Museum, Durham)

Photograph from Wilfred Lambert (referenced below, Plate 5:42)

Ebarat I, the 3rd king in the ShKL, is well-documented in our surviving sources: for example, Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2007, in the Appendix at pp. 230-2) summarised the extensive documentary evidence of his good relations with the Ur III rulers over a period of at least 21 years, from Shulgi 44 (see above) until at least Shu-Sin 8 (the penultimate year of Shu-Sin’s reign).

It is possible that the seal illustrated above belonged to Ebarat’s wife, since the text that it carries reads:

-

“d[Ebar]at, king (lugal), [now-lost female name], his beloved wife”, (see Behzad Mofidi-Nasrabadi, referenced below, number 1, at p. 42).

The completion ‘Ebarat’ is generally accepted, but scholars still debate whether this should be Ebarat I or Ebarat II, the 9th king in the list, since, for example, the seal is stylistically similar to one that belonged to Ili-turam, the servant of Pala-ishshan, a ruler who shortly post-dated Ebarat II (see Behzad Mofidi-Nasrabadi, referenced below, numbers 1, and 2, at p. 42, and sketches of both of them at his Table 2). However, I think that the use of the superscript ‘d’ before Ebarat’s name in the transliteration of the text (which represents the Akkadian cuneiform determinative symbol that indicated his divine status) is a more useful factor for the purpose of dating the seal. Interestingly, as Tonia Sharlach (referenced below, at p. 20) pointed out:

-

“In about his 20th year of his rule, ... Shulgi altered the policy of his father Ur-Namma and began to write his name with the divine determinative: that is to say, Shulgi declared himself a god. This was not without precedent: Naram-Sin, the 3rd king of the Sargonic period, was apparently the first Mesopotamian ruler to have done so ...”.

It therefore seems likely that the ‘Ebarat’ of the inscription had followed Shulgi’s lead when he declared his own divinity. This of itself clearly does not allow us to identify him as Ebarat I, but this identification is further supported by the fact that a surviving administrative document that can be directly associated associated with Ebarat I was dated to the year in which ‘dEbarat became king’ (see below). (Note however that in the ShKL, only the first name, Kirname, is preceded by this ‘divine’ determinative: see Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp, referenced below, at p. 24).

Wilfred Lambert (referenced below, at p. 16), who had examined the seal, observed that:

-

“The composition of the scene seems to be unique. The seated figure [looking left] is certainly male and ... the other two must surely be female.”

He suggested (at p. 17) that the male figure represented Ebarat and:

-

“The figure in front of him [offering what seem to be flowers] will be his wife, and possibly the act was a formal rite by which his successor was designated. [If so, then] the [other] lady ... will be Ebarat's sister.”

I very much doubt that the rite depicted here had anything to do with the succession since, as Behzad Mofidi-Nasrabadi (referenced below, at p. 53) observed, the seal would have been that of Ebarat’s wife. It therefore seems to me that its design would have been intended to emphasise her status as the wife of a deified king: after all, as Tonia Sharlach (referenced below, at p. 21) observed (with reference to Shulgi), the deification of a king clearly affected the status of his wives. In other words, I think that the seal probably depicted the rite by which the lady on the right became the consort of the deified Ebarat I. In this context, we might look again at the fact that, in his 30th year, Shulgi gave one of his daughters in marriage to the ensi of Anshan: on this basis, we might wonder whether Ebarat had similarly married a Mesopotamian princess.

As we have seen, the apparent political stability of this period came to an end when:

-

“Shu-Sin, the [4th] king of Ur, king of the four quarters, destroyed the land of [the Shimashkian] Zabshali", (‘year names of Shu-Sin’, 7b).

As it happens, a body of information about this insurgency survives in the form of a later copy of two inscriptions (one in Akkadian and one in Sumerian) from statues that Shu-Sin commissioned in order to commemorate his victory. As Katrien de Graef (referenced below, 2015, at p. 295) observed:

-

✴the Sumerian inscription (RIME 3/2: 1: 4: 3: Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 1997, at pp. 301-6) recorded that:

-

“... ‘the lands of LU2.SU [= the lands of the Shimashki], the lands of the Zabshali, whose surge is like a swarm of locusts, from the border of Anshan to the Upper [= Caspian] Sea’, threatened the [territory] of Shu-Sin, ... and how [he eventually emerged] victorious”; and

-

✴the Akkadian inscription (RIME 3/2: 1: 4: 5: Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 1997, at pp. 308-12) added the fact that:

-

“... Shu-Sin devastated the lands of Zabshali, Sigrish, Nibulmat, Alumidatum, Garta and Shatilu.”

She observed that the term ‘the Zabshali’ was sometimes used in the inscriptions to describe a confederation of several Shimaskian territories and cities (led by the Zabshali) from [the] extensive territory that stretched from the Caspian Sea to Anshan, each of which had its own governor (ensi). The copyist of the original inscriptions added the information that:

-

✴an enemy prisoner on the ‘Sumerian’ statue was identified on his shoulder as:

-

‘Ziringu, ensi of the land of Zabshali’ (see note 31); and

-

✴a captive ensi on the ‘Akkadian’ statue, who was depicted being trampled under Shu-Sin’s foot, was identified on his shoulder as:

-

‘the man of Indasu’ (see note 32).

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 196) observed, there is no surviving evidence to suggest that Ebarat I was involved in this insurgency. Indeed, he argued that:

-

“In this undertaking, [Shu-Sin] seems to have enjoyed the support of [Ebarat I], who either fought on the side of Ur or at least remained neutral in the conflict. Shu-Sin’s campaign was a success, [and] several of the Shimashkian lands [were] subsequently incorporated into [his territory].”

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 196) observed, Shu-Sin’s victory was soon followed by disaster, when:

-

“... only a few years later, at the very beginning of the reign of [his son and successor], Ibbi-Sin, the last king of the dynasty, ... [Ur] lost control of most of [its] foreign possessions ... [and] the empire effectively ceased to exist.”

One early sign of this gradual collapse is provided by Ishbi-Erra, who started his career as an officer under Ibbi-Sin before rebelling, capturing Isin, and founding his own ‘Isin dynasty’. At this point, he naturally established his own series of year names (see ‘year names of Ishbi-Erra’), many of which overlapped with those of Ibbi-Sin. In the present analysis, I follow the synchronism proposed by Marcel Sigrist (referenced below, at p. 4), in which Ibbi-Sin 24 = Ishbi-Erra 18: on this basis, Ishbi-Erra declared his independence from Ibbi-Sin in Ibbi-Sin’s 7th year, and Ibbi-Sin’s weakness at this time is evidenced by the fact that he was forced to accept this situation for most of the rest of his reign. Steinkeller (as above) then argued that it was in this febrile climate that:

-

“Sensing that the end of Ur was near, Ebarat turned against Ibbi-Sin and occupied Susa ... .”

The evidence for this is in the form of 13 (presumably subsequent) texts from Susa bearing a year name that refers to Ebarat: as Katrien De Graef (referenced below, 2015, at p. 294) pointed out:

-

✴one of these documents is dated to the year in which Ebarat became king (lugal);

-

✴eleven are dated to the following year: and

-

✴the last year name (mentioned above) reads, somewhat confusingly:

-

“Year that the deified Ebarat (dEbarat) became king, year after the year ...”

She also deduced from the original archaeological records that these 13 tablets:

-

“... were found in an Ur III context, no doubt on top of it ...”

Some indication of when Ebarat made his move is given by the ‘year names’ of Ibbi-Sin’, in which we read that:

-

✴in year 5:

-

“... the governor (ensi) of Zabshali married Tukin-hatti-migrisha, [Ibbi-Sin’s] daughter;

-

✴in year 9:

-

“Ibbi-Sin, the king of Ur, went with massive power to Huhnuri, the bolt [= gateway] to the land of Anshan ...”; and

-

✴in year 14:

-

"Ibbi-Sin, the king of Ur, overwhelmed Susa, Adamdun and Awan like a storm, subdued them in a single day and seized the lords of their people"

Katrien de Graef (referenced below, 2015, at p. 293) argued that, since no documents dated later than Ibbi-Sin’s year 3 have been found at Susa, it is likely that he lost control there soon after, and:

-

“... one could interpret the dynastic marriage between [his] daughter and the governor of Zabshali in year 5 as an attempt to (re-)confirm or strengthen the political alliance with Susa's hinterland. It is, after all, [likely] that even the very core of Ur's dominions was in open rebellion shortly after[his] accession to the throne. The attacks on Huhnuri and Anshan in year 9 and on Susa [and Adamdun of the land of] Awan in year 14 [may well indicate] the ultimate convulsions of declining Ur III control on Susa and the Elamite periphery. We know [from archeological data that at least part of Susa] was violently destroyed [at about this time], and it thus seems quite probable that this can be linked with either the conquest of Susa by Ebarat [soon after year 3] or the reaction ... of Ibbi-Sin [recorded in his subsequent] year names. This means that [Ebarat must have taken] control over Susa at sometime between the 3rd and the 9th year of the reign of Ibbi-Sin.”

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2007, at p. 223) had also concluded that:

-

“... the period of Ebarat’s possible control over Susa [must be confined to] the years Ibbi-Sin 4–8.”

Kindattu and Imazu, son of Kindattu

Impression from the seal of Imazu, son of Kindattu, King of Anshan (now in Tehran Museum, tablet 2514)

Image from Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below, Plate 60f, at p. 156)

As we shall see, Kindattu, the 6th king in the ShKL, was:

-

✴the son (as well as the successor) of Ebarat I; and

-

✴the father of Idattu, the 7th king in the ShKL.

We also know the name of another son of Kindattu: the text carried by the seal that produced the impression on a tablet bearing a legal contract (illustrated above) reads:

-

“Imazu, son of Kindattu, lugal (king) of Anshan”, (see Javier Álvarez-Mon, referenced below, at p. 167 and Behzad Mofidi-Nasrabadi, referenced below, number 30, at p. 47).

Imazu is not named in the ShKL: indeed, he is only known from this seal inscription. It is therefore sometimes assumed that the title ‘king of Anshan’ was used here for Kindattu himself (see, for example, Katrien de Graef, referenced below, 2022, at p. 446). However, Behzad Mofidi-Nasrabadi, referenced below, at p. 61) suggested that Kindattu had appointed Imazu as king of Anshan (presumably as a vassal within his wider Shimashkian ‘empire’): he argued that, the seal above, which would have belonged to Imazu :

-

“... is probably intended to show [him] ... receiving a [ceremonial] staff as a sign of office from the king, his father. The new ... theme of the ‘granting of office’ was used again in the following generations”, (my translation).

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2007, at p. 223) observed that, apart Ebarat’s short period of control of Susa early in the reign of Ibbi-Sin:

-

“... we are in total darkness as to where [and for how much longer] Ebarat ruled ... [However], it seems reasonable to think that, for both strategic and logistical reasons, the control of Susa and its region would have been indispensable in allowing Ibbi-Sin to launch a campaign against Huhnuri [in year 9].”

Thus, he argued that Ibbi-Sin regained control of Susa in or shortly before his year 9. Then, in year 14:

-

“Ibbi-Sin, the king of Ur, overwhelmed Susa and Adamdun of the land of Awan like a storm, subdued them in a single day and seized the lords of their people” (‘year names’ of Ibbi-Sin’, 14, see Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2013, p. 296 for the translation ‘Adamdun of the land of Awan’).

It is likely that this ‘victory’ was actually indicative of Ibbi-Sin’s precarious hold on Susa at this time.

We learn something about the political situation in the subsequent period from an administrative document from Isin that was dated to Ishbi-Erra 13 = Ibbi-Sin 19, which Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2007, p. 221 and note 26) translated as follows:

-

“... the envoy of Kindattu (and) his five followers … the envoy of Ida[ttu] (and) his [one] follower; these are the messengers of [Shimashki]”.

This suggests that, by this time, Kindattu:

-

✴had succeeded Ebarat I;

-

✴had delegated some ‘royal’ authority to his son Idattu; and

-

✴had reasonably good relations Ishbi-Erra.

Given what we know about the fragility of Ibbi-Sin’s hold on Ur itself at this time, it is likely that Kindattu had also secured control of Susa. Thus, as the fortunes of Ibbi-Sin deteriorated, Kindattu, with the assistance of at least two sons, came to presided over a vast territory that included the Shimashki lands, Susa and the surrounding plain, and Anshan.

We then read in the respective year name lists that, in Ibbi-Sin 22 = Ishbi-Erra 16:

-

✴Ibbi-Sin, the king of Ur, secured Ur and …, stricken by a hurricane, ordered by the gods which shook the whole world; and

-

✴Ishbi-Erra, the king, smote the armies of Shimashki and Elam.

Furthermore, we learn about Kindattu’s part in these dramatic events from two separate sections of a panegyric to Ishbi-Erra known as ‘Hymn B: Ishbi-Erra and Kindattu’, which celebrated his victory:

-

✴In the first of these, which is extremely lacunose, we read that:

-

“From Bashimi by the edge of the sea ...... to the edge of Zabshali ......, and from Uru’a (Arawa), the bolt of Elam ...... to the edge of Marhashi .......Kindattu, the man of Elam, ....... ...... Isin, the great spindle of heaven and earth. The king's battle did not ....... The battle of Elam ...... Sumer. ...... by the edge of the sea. ...... the land of Huhnuri. ...... the wild animals and four-footed ....... The king ...... in the battle”, (segment C).

-

✴In the second of these, we read that:

-

“... the news was carried to Kindattu, the man of Elam; the Anshanites and Shimashki gave a battle cry; he (Kindattu) approaches the mountains; he addresses his assembled army”, (segment E, see also the translation by Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2007, at p. 224, note 34).

As Katrien de Graef (referenced below, 2022, at p. 446) observed, it seems that Ibbi-Sin had faced an Elamite attack on Ur, only to be saved by Ishbi-Erra, and the second passage of the panegyric clearly establishes that Kindattu, the man of Elam, was the commander of ‘the armies of Shimashki and Elam’ in an alliance that included the Anshanites.

Ibbi-Sin’s 23rd year was listed as the year in which:

-

“... the stupid monkey in the foreign land struck against [him]”, (‘year names’ of Ibbi-Sin’, 23).

We learn in later literary sources that this referred to another invasion of Ur by Kindattu. This time, there was to be no salvation for Ibbi-Sin:

-

✴The ‘Lament for Ur’ recorded that:

-

“The good house of the lofty untouchable mountain, E-kish-nu-gal, [the residence of the moon god Nanna and his wife Ningal], was entirely devoured by large axes. The people of Shimashki and Elam, the destroyers, counted its worth as only 30 shekels. They broke up the good house with pickaxes. They reduced the city to [ruins]. ... Ningal cried, ‘alas, my city,’ and ‘alas, my house‘ .... O Nanna, the shrine of Ur has been destroyed and its people have been killed”, (lines 241-9).

-

✴The roughly contemporary ‘Lament for Sumer and Ur’ similarly recorded that the gods had decided that Ibbi-Sin’s subjects:

-

“... should no longer dwell in their quarters [but] ... should be given over to live in an inimical place; that Shimashki and Elam, the enemy, should dwell in their place; that their shepherd, [Ibbi-Sin hmself], should be captured by the enemy in his own palace and like a swallow that has flown from its house, should [be taken] from Mount Zabu on the edge of the [Babylonian marshes] to the borders of Anshan, never to return to his city”, (lines 33-7, my changed word order).

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2007, at p. 224, note 35) reproduced another text fragment (ACh Ishtar LXVII rev. ii 11–12, which I have not been able to identify), which he translated as follows:

-

“... the reign of destruction of Ibbi-Sin, king of Ur, who, in tears, went as captive to Anshan”.

Ishbi-Erra lived to fight another day: the ‘year name of Ishbi-Erra’, 26 records that:

-

“Ishbi-Erra, the king, [drove] out of Ur,... the Elamite who was dwelling in its midst.”

It is possible that, by this time, the Elamite in question was Idattu, the son and successor of Kindattu (see below).

Interestingly, the earliest known recensions of Sumerian King List following that of Shulgi (mentioned above), which were probably written during the reign of one of Ishbi-Erra’s early successors at Isin) make mention of the part played by Kindattu in the fall of Ur: they simply record that, after Ibbi-Sin had ruled for 24 years:

-

“Ur was struck down with weapons (and) the kingship was carried off to to Isin, [where] Ishbi-Erra was king”, (composite translation at CDLI: P479895, lines 351-5).

Idattu I, son of Kindattu

Royal Inscription of Idattu I (MS 4476 in the Martin Schøyen Collection, Oslo)

Image from the website of the collection

As we have seen, Idattu I was the 7th king in the ShKL. Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2007, at pp. 221-2 and note 28) published an inscription on the lower surface of a shallow bowl of unknown provenance (illustrated above) that is is now part of the (private) Schøyen Collection in Oslo. He translated the inscription, which is ‘written’ in classical Ur III script, as follows:

For Idattu, grandson of Ebarat [I], son of Kindattu, the shepherd of Utu, the beloved one of Inanna,

king of Anshan (lugal Anshanki), king of Shimashki and Elam (lugal Shimashki ú Elam-ma)

Kiten-rakittapi, the chancellor (sukkalmah) of Elam and high judge (teppir), his servant

fashioned (this object) for him

Interestingly, this inscription contains the first surviving evidence for the important posts of chancellor (sukkkalmah) of Elam and high judge (teppir).

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2007, at pp. 228-9) argued that this inscription demonstrates that the ShKL:

-

“... is built around a genuine dynastic tradition, which centres on the line of Ebarat I:

-

✴Ebarat I [himself] (no. 3):

-

✴Kindattu (no. 6); and

-

✴Idattu I (no. 7).

-

... Apart from having continued for at least [three] generations, that tradition was also associated with ... Ebarat’s original kingdom, which gradually swallowed up Anshan and other Shimashkian territories and eventually came to embrace Susa and the Susiana as well.”

Katrien de Graef (referenced below, 2015, at p. 296) argued that three administrative tablets from Susa with unattributed year names should probably be placed in the reign of Idattu I. If this is correct, then, by at least the time of Idattu I, the ‘Shimaski kings’ ruled at Susa as well as at Anshan, Elam and Shimashki.

Tan-Ruhurater (8)

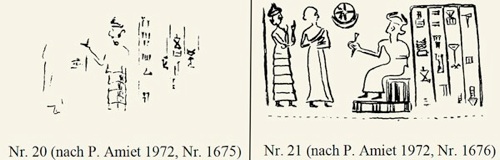

Sketches of the impressions made by two seals from Susa:

Left: Ensi Tan-Ruhurter, from Behzad Mofidi-Nasrabadi (referenced below, number 20, at p. 45 and Table 8)

Right: Great Queen Mekubi, from Behzad Mofidi-Nasrabadi (referenced below, number 21, at p. 45 and Table 9)

P. Amiet 1972= Pierre Amiet, referenced below

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2007, at pp. 228-9 and note 50) observed that the genealogical line of Ebarat I - Kindattu - Idattu I continued with Tan-Ruhurater (8), who is known to have been the son of Indattu I:

-

✴the text IRS 9, which is stamped on two bricks from Susa, recorded:

-

"Idattu, beloved by Inshuhinak, king of Shimashki and Elam; [and] Tan-Ruhurater, son ..." :

-

✴the inscription of Shilhak-Inshushinak (EKI 48) recorded Tan-Ruhurater, son of Idattu (at line 17); and

-

✴the text carried by a seal from Susa (see Behzad Mofidi-Nasrabadi, referenced below, number 20, at p. 45, sketched on the left above) recorded Tan-Ruhurater, ensi of Susa, ... son of Idattu.

Katrien de Graef (referenced below, 2015, at p. 296) argued that an administrative tablet from Susa with an unattributed year name should probably be attributed to Tan-Ruhurater, since:

-

“... the text mentions his house or palace (e2 tan-dru-hu-ra-/te-er)” (see MDP 28, 505, reverse line 1)’

According to Daniel Potts (referenced below, at p. 140):

-

“Tan-Ruhurater was ... [a] son-in-law of Bilalama of Eshnunna, himself a contemporary of Shu-ilishu, [the second king of Isin, traditionally (1986–1977 BC].”

Robert Whiting (referenced below, Figure 1, at p. 28) established the family links between Shu-ilishu, Bilalama and Tan-Ruhurater and identified the daughter of Bilalama who was married to Tan-Ruhurater as Mekubi. The text stamped on eight (now fragmentary) bricks from Susa relate to the building of a temple to Inanna:

-

✴four of them (IRS 4, bricks 24-7) bear the name of Tan-Ruhurater, ensi of Susa; and

-

✴the other four (IRS 5, bricks 28-31) bear the name of Mekubi, daughter of Bilalama, ensi of Eshnunna, well-loved wife of [Tan-Ruhurater].

Interestingly, in a seal from Susa (see the sketch on the right above), a scribe (dub.sar) called Aabanda described himself as the servant of the great queen (nin.gu.l[a]) Mekubi (see Behzad Mofidi-Nasrabadi, referenced below, number 21, at p. 45).

Katrien de Graef (referenced below, 2021, at p. 51 and notes 6 and 7) observed that Shu-Ilishu claimed to have:

-

✴returned the statue of Nanna, which the Elamites took as booty to their homeland:

-

“... when he brought (back the statue of) the god Nanna from Anshan to Ur”, RIME 4: 1: 2: 1, lines 5-11); and

-

✴resettled the scattered people of Ur (implying that there [had been] an exile of at least a part of Ur’s population):

-

“... [when] he establish[ed in] U[r the people] scattered as far as A[nshan], in their abode”, (RIME 4: 1: 2: 2, lines 27’-28’).

We might reasonably assume that:

-

✴the seizure of the statue of Nanna from Ur and the exile of at least some of its people had occurred when Ur had fallen to Kindattu in Ibbi-Sin year 24; and

-

✴ Shu-Ilishu retrieved them from Anshan at the time of Tan-Ruhurater.

Unfortunately, the surviving records do not indicate whether Shu-Ilishu used military or diplomatic means to secure the retrieval of Nanna and the repatriation of the exiles.

Katrien de Graef (referenced below, 2022, at p. 449) argued that Tan-Ruhurater, who:

-

“... was probably Indattu I’s son, did not succeed as king. He was governor (ensi) of Susa.”

It is true that he is not documented as lugal in any of our surviving sources except for the Shimaski king list, but that does prove that he never acceded to the throne: indeed, in my view, the fact that Mekubi was described as the ‘great queen’ (see above) suggests that he did. However, it is also entirely likely that his rule was undermined by external pressure:

-

✴as noted above, Shu-Ilishu might have used force to retrieve the statue of Nanna from Anshan and to repatriate the people of Ur who were living in exile there; and

-

✴as de Graef pointed out, Ilum-muttabbil, governor of Der (nominally an ally of Tan-ruhurater’‘s father-in-law) claimed to have been:

-

“... the smiter of the head of the army of Anshan, Elam and Shimashki”, (RIME 4: 12: 2: 1, lines 9-14).

Idattu II (10)

Impression from the seal of Kuk-Simut, judicial official (teppir) of Idattu II (now in the Musée du Louvre, SB 2294)

Image from Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below, Plate 60g, at p. 157)

As Piotr Stenkeller (referenced below, 2007, at p. 229, note 50) observed, Tan-Ruhurater (8) is followed in the ShKL by:

-

“... Ebarat II (9) and Idattu II (10). While the familial relation of Ebarat II to the other Shimashkians is unclear [see below], Idattu II [was certainly a] son of Tan-Ruhurater.”

For example, the text stamped on number of bricks from Susa (IRS 6-7, which come in two vvariants of the same text, one in Akkadian and the other in Sumerian) ) record him as ensi of Susa, son of Tan-Ruhurater:

-

“To Inshushinak, his lord, for (his) life, Idadu, the ensi of Susa, the beloved servant of Inshushinak, the son of Tan- Ruhuratir, did not refurbish the ancient wall in bitumen (but) built a new wall in baked bricks at the back of the Ekikuanna[= temple of Inshaksununa]; he had (it) built for his life”, (IRS 6-7, translated by Florence Malbran Labat, referenced below, 2018, note 11, at p. 475).

The same filiation is recorded in the (Sumerian) text on a seal from Susa (illustrated above), which reads:

-

“Idattu, ensi of Susa, beloved hero of Inshushinak, son of Tan-Ruhurater, had given (this seal) to the judicial official (teppir), Kuk-Simut, his beloved servant”, (translation by Javier Álvarez-Mon, referenced below, at p. 167, my changed word order; see Jan Tavernier, referenced below for the translation of ‘teppir’).

Javier Álvarez-Mon (as above) suggested that this scene might well depict the seated Idattu II investing Kuk-Simut as teppir by presenting him (via the figure in the centre) with a ceremonial axe , which was:

-

“... clearly a symbol of ministerial dignity.”

However, the important point is that the entry in the ShKL is the only surviving source in which Idattu II is identified as a king.

Ebarat II (9)

Hollow cylinder of Atta-hushu commemorating the foundation of a Nanna, from Susa

Now in the Musée du Louvre (SB 15440), image from museum website

As Katrien de Graef (referenced below, 2022, at p. 451) observed, Ebarat II, who is listed between Tan-Ruhurater (8) and Idattu II (10) in the ShKL, is probably the ‘Ebarat’ who is mentioned without affiliation in the inscription of Shilhak-Inshushinak (EKI 48, at line 21). Although he might have been a son of Tan-Ruhurater (perhaps the older brother of Idattu II), this is by no means certain.

Katrien de Graef (referenced below, 2012, at p. 535 and note 32) reproduced a re-reading by Jean-Jacques Glassner (referenced below) of the inscription on the cylinder illustrated above:

-

“For Ebarat, lugal (king) of Anshan and Susa: when Shilhaha was sukkalmah (chancellor) and ADDA LUGAL (father of the land) of Anshan and Susa, Atta-hushu, son of the sister of Shilhaha, built the temple of Nanna”.

She added that Glassner had suggested, on the basis of this new reading, that:

-

“... Ebarat II ruled as king over Anshan and Susa while Shilhaha, being his sukkalmah, exercised authority in his name over Elam and/or Shimashki.”

She concluded (at p. 536) that, at the time of the inscription, each of:

-

“... Ebarat II, Shilhaha and Atta-hushu [seems to have] exercised their power on a different level and/or in a different area ... :

-

✴Ebarat II ruled as king over Anshan and Susa;

-

✴Shilhaha was his sukkalmah in Elam (or in Shimashki and Elam); and

-

✴Atta-hushu was [Shilhaha’s] sukkal [deputy] and teppir [judicial official] in Susa.”

I discuss the relationship between Ebarat II, Shilhaha and Atta-hushu on the following page: the important thing in the present context is that Ebarat II is named as ‘king of Anshan and Susa’ in thisn Akkadian inscription some 500 years before the title next appears (in Elamite) in our surviving sources.

Seal of Kuk-tanra from Susa, servant of Shilhaha and modern impression

Now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb 6225), image from museum website

See also Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below, Plate 60d, at p. 157)

The seal illustrated above carries the text:

-

“Ebarat, king (lugal): Kuk-dKalla, son of Kuk-sharum, servant of Shilhaha.”

Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below, at p. 167) suggested that the seated figure represents Ebarat II, and that he offered a small cup to a man representing Kuk-dKalla, who is led by a lama (a protective goddess who often appears in presentation scenes, usually as an intermediary between a god or king and a mortal). He observed that the presence of the lama suggests that Ebarat II was ‘co-opting’ divine imagery’, and suggested that he may have been ‘tempted by deification’. Interestingly, some decades before, a similar ‘presentation’ scene had been depicted on a seal of Hash-hamer, the governor of Ishkun-Sin in the reign of Ur-Namma, is now in the British Museum (see above).

Map from Wikipedia (my additions in white)

Abbreviations

EKI = König, F. W., “Die Elamischen Königsinschriften”, (1965) Graz

MDP 11 = Scheil V., “Mélanges Épigraphiques: Mémoires de La Mission Archéologique de Perse, 28”, (1911) Paris

MDP 28 = Scheil V., “Mélanges Épigraphiques: Mémoires de La Mission Archéologique de Perse, 28”, (1939) Paris

IRS = Malbran-Labat F., “Les Inscriptions Royales de Suse: Briques de l'Époque Paléo-Élamite à l'Empire Néo-Élamite”, (1995) Paris

Other references:

Verderame L., “The Seal of Hašhamer, Iškun-Sîn, and Ur III Kingdom’s Early Development”, in:

Greco A. and Spada G., “And I Have Also Devoted Myself to the Art of Music” Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Franco D’Agostino Presented on His 65th Birthday by His Pupils, Colleagues, and Friends”, (2025) Rome

de Graef K., “The Middle East after the Fall of Ur: From Ešnunna and the Zagros to Susa”, in:

Radner K. et al. (editors), “The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Vol. II: From the End of the Third Millennium BC to the Fall of Babylon”, (2022) New York, at pp. 407-95

de Graef K., “Bad Moon Rising: The Changing Fortunes of Early Second-Millennium BCE Ur”, in:

Frame G. and Pittman H. (editors), “Ur in the Twenty-First Century CE: Proceedings of the 62nd Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Philadelphia, July 11–15, 2016”, (2021) University Park, PA, at pp. 49-87

Álvarez-Mon J., “The Art of Elam (ca. 4200–525 BC)”, (2020) Abingdon and New York

Surdi M., “On the Alleged Inscribed Bricks of Naram-Suen from Susa”, Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires”, 1 (2020) 1-4

Khramov Y., “Kurigalzu’s Campaign in Elam and Elamite-Babylonian Synchronisms: Part II”, (2019) on-line

Steinkeller P., “History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays”, (2019) Boston and Berlin

Malbran-Labat F., “Elamite Royal Inscriptions”, in:

Álvarez-Mon J. et al. (editors), “The Elamite World”, (2018) Oxford and New York, at pp. 464-80

Patterson D. W., “Elements Of The Neo-Sumerian Military”, (2018) thesis of the University of Pennsylvania

Peyronel L, “The Old Elamite Period”, in:

Álvarez-Mon J. et al. (editors), “The Elamite World”, (2018) Oxford and New York, at pp. 203-31

Steinkeller P., “The Birth of Elam in History”, in:

Álvarez-Mon J. et al. (editors), “The Elamite World”, (2018) Oxford and New York, at pp. 177-202

Sharloch T. M., “An Ox of One’s Own: Royal Wives and Religion at the Court of the Third

Dynasty of Ur”, (2017) Berlin and Boston

Basello G-P., “Elamite Kingdom”, in:

MacKenzie J. M. and Dalziel N. R. (editors), “The Encyclopedia of Empire” (2016) Chichester, at pp. 788-97

Potts D. T., “The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State; Second Edition”, (2016), New York and Cambridge

de Graef K,, “Susa in the Late 3rd Millennium: from a Mesopotamian Colony to an Independent State (MC 2110-1980)”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp.289-96

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I., “Part I: Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp.1-130

Steinkeller P., “On the Dynasty of Šimaški: Twenty Years (or so) After”, in:

Kozuh M, el al, (editors), “Extraction & Control: Studies in Honor of Matthew W. Stolper”, (2014), Cicago Ill, at pp. 287-96

Glassner J.-J., "Les Premiers Sukkalmah et les Derniers Rois de Šimaški”, in:

de Graef K. and Tavernier J. (editors), “Susa and Elam: Archaeological, Philological, Historical and Geographical Perspectives: Proceedings of the International Congress held at Ghent University, December 14–17, 2009”, (2013) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 319-28

Marchesi G.., “Ur-Nammâ(k)'s Conquest of Susa”, in:

de Graef K. and Tavernier J. (editors), “Susa and Elam: Archaeological, Philological, Historical and Geographical Perspectives: Proceedings of the International Congress Held at Ghent University, December 14–17, 2009”, (2013) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 285-91

Steinkeller P., “Puzur-Inshushinak at Susa: A Pivotal Episode of Early Elamite History Reconsidered”, in:

de Graef K. and Tavernier J. (editors), “Susa and Elam: Archaeological, Philological, Historical and Geographical Perspectives: Proceedings of the International Congress Held at Ghent University, December 14–17, 2009”, (2013) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 293-318

de Graef K., “Dual power in Susa: Chronicle of a Transitional Period from Ur III via Šimaški to the Sukkalmaḫs”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 75:3 (2012) 525-46

Mofidi-Nasrabadi B, “Aspekte der Herrschaft und der Herrscherdarstellungenin Elam im 2. Jt. v. Chr.”, (2009) Münster

Steinkeller P., “Camels in Ur III Babylonia?” in

Schloen D. J., “Exploring the Longue Durée: Essays in Honor of Lawrence E. Stager”, (2009) Winona Lake, at pp. 415-9

Frayne D. R. (2008a), “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Volume 1: Presargonic Period (2700-2350 BC)”, (2008) Toronto

Frayne D. R. (2008b), “The Zagros Campaigns of the Ur III Kings”, Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies, 3 (2008) 33-56

Steinkeller P., “New Light on Šimaški and Its Rulers”, Zeitschrift für Assyrologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, 97:2 (2007) 215-32

Tavernier J. M., “The case of Elamite Tep-/Tip- and Akkadian Tuppu", Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies" 44 (2007) 57-69

Frayne D. R., “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Early Periods, Vol. 3/2: Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC)”, (1997) Toronto, Buffalo and London

Sigrist M., “Isin Year Names’, (1988) Berrien Springs MI

Whiting R, M., “Old Babylonian Letters from Tell Asmar”, (1987) Chicago ILL

Lambert W. G., “Near Eastern Seals in the Gulbenkian Museum of Oriental Art, University of Durham”, Iraq, 41:1 (1979) 1-45

Amiet P., “Glyptique Susienne desOorigins à l’Époque des Perses Achéménides: Cachets, Sceaux Cylindres et Empreintes Antiques Découverts à Suse de 1913 à 1967,” Mémoires de la Délégation Archéologique en Iran, 43”, (1972) Paris

Foreign Wars (3rd century BC)

Home