Persian Empire

Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great, 559 - 530 BC)

Main page: Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great, 559 - 530 BC)

Topic: History if Anshan

Persian Empire

Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great, 559 - 530 BC)

Main page: Cyrus II (Cyrus the Great, 559 - 530 BC)

Topic: History if Anshan

History of Anshan

Period to ca. 700 BC

The recorded history of Anshan goes back to ca. 2300 BC, when it was conquered by King Manistushu of Akkad and incorporated into what was then the Akkadian province of Elam. A king of Anshan (Imazu, son of Kindattu) was recorded in ca. 2000 BC, but (as far as we know) for the next millennium or more, it formed part of an Elamite kingdom that was usually known as the Kingdom of Susa and Anshan.

Location of Anshan

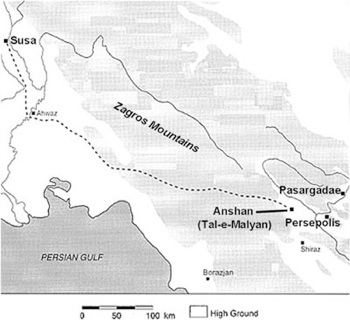

Map of Southwestern Iran, showing Anshan and Susa

Adapted from David Stronach (referenced below, 2013, Figure 2, at p. 57)

Archeologists discovered location of Susa (on the eastern edge of Mesopotamia) in the 1850s (or our era) but, as Antigoni Zournatzi (referenced below, 2019, at p. 151) observed, it was only in the the early 1970s that the discovery of:

“... various epigraphic and archaeological clues [began] to indicate that the ‘lost’ city of Anshan could [in fact] be identified with the important ancient urban centre whose remains survive at Tal-i Malyan [see the map above], in close proximity to [the later Persian cities of] Pasargadae and Persepolis.”

John Hansman (referenced below, on-line) summarised the result of the excavations carried out at Tal-i Malyan at this time:

“The site is surrounded by a rectangular wall of mud-brick construction, now much eroded, which measures approximately 1 km by 0.8 km. ... The distribution of later pottery suggests that the major occupation at [the site] (some 130 hectares) occurred during the later centuries of the 3rd millennium and continued into the early centuries of the 2nd millennium BC.”

Identification of the Site of Ancient Anshan at Tal-i Malyan

So-called ‘Anshan brick’ published by Maurice Lambert (referenced below)

Image adapted from his photographs at p. 62

As Erica Reiner (referenced below, at p. 8) observed, although several inscribed bricks were found during the excavations at Tal-i Malyan:

“... none of the inscriptional material found at [the site] contained a reference to Anshan. [All that could be said] was that the fragments of inscribed bricks:

✴represented inscriptions of Hutelutush-Inshushinak, [who was styled as lord (menir) of Elam and Susa’ in ca. 1120 BC]; and

✴duplicated an incomplete inscription on two bricks of unknown provenience in private collections.

[However], ... with the publication of the ‘Anshan brick’ [illustrated above] by Maurice Lambert, and the comparison of its unique features with those of the Tal-i-Malyan bricks, it has become evident that the Anshan brick and the two incomplete inscriptions in private collections all come from Tal-i Malyan.”

According to Maurice Lambert (referenced below, at p. 61), the ‘new’ brick had apparently been found ‘between Shiraz and Persepolis’. The inscription was written in vertical columns that are read from left to right and top to bottom on two sides of the brick (which was presumably used at a corner, so that the two inscribed faces were visible). Most of the text was known from other examples, but the last two lines are not found elsewhere: Lambert translated them (at p. 66) as follows:

“... and, at Anshan, I, [Hutelutush-Inshushinak], designed and built in baked bricks a siyan tarin (temple of the alliance) of Napirisha, Kiririsha, Inshushinak and Simut”, (my translation of Lambert’s French).

Although the provenance of this important inscription is not completely secure, parts of the same text have been found throughout the site at Tal-i Malyan. Thus, for example, Daniel Potts (referenced below, at p. 240), citing Lambert, asserted that:

“Inscribed bricks from Tal-i Malyan, ancient Anshan, proclaim that Hutelutush-Inshushinak built a baked brick temple there to Napirisha, Kiririsha, Inshushinak and Shimut, and it is probable that some of the texts found there relate to that project.”

History of Anshan (ca. 1000 - 700 BC)

Matt Waters (referenced below, 2023, at p. 387) pointed out that, on the basis of the present archeological evidence, the site at Tal-i-Malyan seems to have been abandoned by ca. 1000 BC (although it is important to bear in mind that mush of the site remains un-excavated). However, there is no evidence that that the political status of Anshan changed at this time: the last securely documented king of Anshan and Susa was Shutruk-Nahhunte II (717-699 BC).

Anshan, Elam and the Assyrians

Battle at Halule (691 BC)

A record in the annals of the Assyrian king Sennacherib (705-681 BC) recorded that, at that time, the Elamite king Huban-menanu:

“... whose cities I [Sennacherib] had conquered and ruined in my earlier campaign in the land of Elam. ... [On receiving this] bribe, [Huban-menanu] assembled his army ... The [highlanders] of Parsuash, Anzan (Anshan), Pasheru [and] Ellipi, [together with lowland Chaldeans, Arameans and Babylonians], a large host, formed a confederation with him. In their multitude, they took the road to Akkad and, as they were advancing towards Babylon, they met up with Shuzubu (Mušshēzib-Marduk), a Chaldean (who is) the king of Babylon, and banded their forces together.... They drew up in battle lines to confront me at the city Halule, which is on the bank of the Tigris ...”, (RINAP 3, 23: v: 29-47).

We later read that, in the battle:

“I [Sennacherib] quickly slaughtered and defeated Huban-undasha (Humban-undasha), nāgiru of the king of Elam, chief commander of the armies of Elam ...”, (RINAP 3, 23: v: 71 - see the translation by Wouter Henkelman, referenced below, 2008, at p. 21, note 35).

Although the Babylonians claimed victory on this occasion, subsequent accounts indicate that this was a somewhat premature claim (as we shall see).

The Assyrian account of these events is important for our present purposes because of the mention of the Anshanites as allies (rather than subjects) of Elam. Matt Waters (referenced below, 2000) argued that:

✴it seems that Huban-menanu himself had formed the anti-Assyrian alliance (see p. 34); and

✴the inclusion of Parsuash and Anshan among the allies:

“... suggests Huban-menanu’s ability to command contingents from that region ..., [which, in turn] demonstrates some levels of Elamite political influence in Fars in the early 7th century” (see p. 35).

Kiumars Alizadeh (referenced below, at p. 28) agreed with these general observations, although he did not accept that Water’s assertion that Parsuash was in Fars: rather, he argued (at p. 29) that:

“... it would be better to search for Parsuash ... in the central Zagros region and not necessarily in the south and at the border of Anshan.”

The key point for the present discussion is that, while Huban-menanu could call on the Anshanites for men to fight under his field-commander Huban-undasha at Halule, it is entirely possible that the man who sent (and possibly led) the Anshanite contingent was recognised as ‘king of Anshan’.

[More to follow]

The territory of Anshan continues to appear in our surviving sources until the time of Darius (who seized control of the ‘Persian Empire’ some eight years after Cyrus’ death).

References:

Waters M. W., “The Persian Empire under the Teispid Dynasty: Emergence and Conquest”, in:

Radner K. et al. (editors), “The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East: Vol. V: The Age of Persia”, (2023) New York, at pp. 376-416

Alizadeh K., “The Earliest Persians in Iran: Toponyms and Persian Ethnicity”, Digital Archive of Brief Notes and Iran Review (DABIR), 7 (2020) 16-53

Zournatzi, A., “Cyrus the Great as a ‘King of the City of Anshan’”, Tekmeria, 14 (2019) 149-80

Potts D. T., “The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State; Second Edition”, (2016), New York and Cambridge

Stronach D., “Cyrus and the Kingship of Anshan: Further Perspectives”, Iran, 51:1 (2013) 55-69

Henkelman, W. F. M., “The Other Gods Who Are: Studies in Elamite-Iranian Acculturation Based on the Persepolis Fortification Tablets”, (2008) Leiden

Waters M. W., “A Survey of Neo-Elamite History”, (2000) Helsinki

Hansman J., “Anshan”, Encyclopaedia Iranica, 2:1 (1985) 103-7, see updated page on-line

Reiner E., “The Location of Anshan”, Revue d'Assyriologie, 67 (1973): 57–62

Lambert M., “Hutéludush-Insushnak et le Pays d’Anzan”, Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archéologie Orientale, 66 (1972) 61-76