Elamite Dark Age (ca. 1100 - 760 BC)

François Bridey (referenced below, at pp. 180-1) observed that, after the catastrophic invasion of Elam by King Nebuchadnezzar I of Babylon:

-

“... the dark ages [began] for Susa and its region, at a time when Indo-Iranian peoples ... were gradually migrating into the Iranian region [around Anshan. ... However], the ancient monarchy of Susa and Anshan enjoyed a brief resurgence in the 8th and 7th centuries BC, ... a period contemporary with the height of the Assyrian empire ...”

This exemplifies what Alexa Bartelmus (referenced below, at p. 608) characterised as an:

-

“... established trend in modern Elamite studies: namely:

-

✴to treat the three centuries [or more of] the so-called ‘Dark Age’ as if it were a poisonous lake, hostile to any higher forms of life; and

-

✴to deny the possibility that [anything of significance happened] within that time span.”

Neo-Elamite Dynasties

Image adapted from Elynn Gorris (referenced below, 2021, at p. 2): content unchanged

As Elynn Gorris (referenced below, 2021, at p. 2) observed:

-

✴the first Neo-Elamite king attested in the surviving part of the so-called ‘Babylonian Chronicle’ (see ABC 1, i: 9-10) was Huban-nikash I (Ummanigash), who ascended to the throne in Elam in 743 BC;

-

✴he must have been preceded by the unknown Elamite ruler who received greeting gifts from the Babylonian king Nabu-shuma-ishkun (760–748 BC - see CM 52 iii 7, iii 21–2); and

-

✴this predecessor was presumably Huban-tahra, who is named (as Umbadarâ) as the son of Huban-nikash I (Ummanigash) in the annals of Ashurbanipal (see, for example, Prism F, v: 36).

The Babylonian Chronicles also record that:

-

“[After] Huban-nikash I (Ummanigash) [had] ruled Elam for 26 years, Shutruk-Nahhunte II (Istra-hundu), his sister's son, ascended the throne in Elam”, (ABC 1, i: 38-40).

Since Shutruk-Nahhunte II named his father as Huban-immena (see below), he must have married the sister of Huban-nikash.

Matt Waters (referenced below, 2000, at p. 10) pointed out that:

-

“After Hutelutush-Inshushinak [I], no Elamite royal inscriptions are extant until the reign of Shutruk-Nahhunte II (717-699 BC) [see below]”.

From this point, we can trace this dynasty more easily:

-

✴Shutruk-Nahhunte II ruled for 18 years and was succeeded by his brother, Hallutush-Inshushinak (ABC 1, ii: 32-35);

-

✴Hallutush-Inshushinak ruled for 6 years and was succeeded by Kutur-Nahhunte (ABC 1, iii: 8-9);

-

✴Kutur-Nahhunte ruled for 10 months and was succeeded by Huban-menanu (ABC 1, iii: 8-9);

-

✴Huban-menanu ruled for 4 years (ABC 1, iii: 26); and

-

✴the so-called ‘Walters Art Gallery Sennacherib Inscription’ (transliterated and translated by Kirk Grayson, referenced below, at pp. 88-96) recorded Huban-menanu as:

-

•the son of Hallutush-Inshushinak (line 16); and

-

•the brother of Kutur-Nahhunte (line 19).

Shutruk-Nahhunte II (717-699 BC)

Evidence for the identity of ‘king Shutur-Nahhunte, son of Huban-mena’ in EKI 71

Royal titles of EKI 71-3 from Matt Waters (referenced below, at pp. 111-2, entries 2, 4 and 5 respectively)

Identifying Shutruk-Nahhunte, Son of Huban-immena

An Elamite king called Shutruk-Nahhunte, son of Huban-immena is known from two surviving Neo-Elamite ‘royal’ inscriptions from the ‘acropolis’ at Susa:

-

✴EKI 72, which is known from copies of the text on three fragmentary square slabs (discussed further below); and

-

✴EKI 73, which is known from three surviving fragments (A-C) of a stele.

The similarly-named ‘Shutur-Nahhunte, son of Huban-immena’, is recorded in EKI 71, which survives on two alabaster horns (A and B) dedicated to the goddess Pinigir at Susa (see Elynn Gorris, referenced below, 2020, at p.30).

The table above summarises the overlap in the royal titles used by:

-

✴Shutruk Nahhunte I, on EKI 22 (the stele of Naram-sin - see above);

-

✴Shutur-Nahhunte , in EKI 71; and

-

✴Shutruk Nahhunte II, in the inscriptions EKI 72-3.

This overlap (and the fact that the subjects of EKI 71-3 are all described as the son of Huban-immena) supports the identification of the subject of EKI 71 as Shutruk Nahhunte II. However, as Jan Tavernier (referenced below, 2004, at p, 7) acknowledged, some scholars have expressed doubts about whether the names Shutur-Nahhunte and Shutruk-Nahhunte could belong to one individual. He therefore re-visited the problem on the basis of a detailed linguistic analysis, and concluded (at p. 16) that:

-

“... in all probability, [all three inscriptions] were recorded during the reign of Shutruk-Nahhunte II, despite the onomastical problem of two different names for one king.”

Elynn Gorris (referenced below, 2020, at p. 32) observed that:

-

“... Shutruk Nahhunte II re-used the titulary of the Middle Elamite Shutrukid dynasty, especially [that] of his namesake Shutruk Nahhunte I ... Only one new title menku likki Hatamtik (ruler protecting Elam) was added (to EKI 72-3) to the Shutruk Nahhunte II titulary,”

Shutruk-Nahhunte II and EKI 72

The most complete of the three surviving inscriptions EKI 72

Image from the website of the Louvre, where the inscriptions are housed (but not exhibited)

The inscription EKI 72, which is the longest of the three known royal inscriptions of Shutruk-Nahhunte II, begins:

-

“I, Shutruk-Nahhunte, son of Huban-immena:

-

✴likume rishakka (expander of the kingdom);

-

✴katru hatamtuk (holder of the throne of Elam);

-

✴menku likki hatamtuk (holder of the sovereignty of Elam);

-

✴libak hanik (beloved servant of) the Great God [Napirisha] and of Inshushinak”, (lines 1-4, my translation of the French given by Florence Malbran-Labat, referenced below, IRS 57, at p. 135).

Although the precise translation of the royal titles is not possible, it is clear that this inscription implies the title ‘King of Elam’, albeit that, in this case, the title ‘King of Anshan and Susa’ is apparently omitted.

Jan Tavernier (referenced below, 2011, at p. 346) translated lines 5-11 as follows:

-

“After:

-

✴King Hutelutush-Insusinak, King Silhnahamru-Lagamar and King Humban-immena, three important kings, had surrounded me;

-

✴I, Shutruk-Nahhute, had seized [the Elamite] sovereignty; and

-

✴Inshushinak had helped me;

-

I [destroyed ?? - see his note 10 on p. 345] and protected the kukunnum, I seized Karintash for Inshushinak and I [established his observance there ?]”, (my translation of Tavernier’s French, my punctuation, and my additions in square brackets).

If I have understood Tavernier’s translation correctly, then it seems that, according to the propaganda of Shutruk-Nahhunte II, he had:

-

✴seized the sovereignty of Elam with the help of Inshushinak and three earlier Elamite kings (Hutelutush-Insusinak, Silhnahamru-Lagamar and Humban-immena); and

-

✴rewarded Inshushinak by seizing Karintash and (probably) by establishing his cult there.

Jan Tavernier (referenced below, 2011, at p. 344, note on lines 5-7) suggested that:

-

✴King Hutelutush-Inshushinak here was probably the son and successor of Hutelutush-Inshusinak (ca. 1120-1110 BC); and

-

✴King Silhnahamru-Lagamar (ca. 1100 BC) was probably his younger brother and successor.

This hypothesis is reflected in the family tree of the Middle-Elamite Shutrukids illustrated above. This brings us Humban-immena, a name that appears twice in the inscription:

-

✴the Humban-immena of line 1 was the father of Shutruk-Nahhunte II; and

-

✴the Humban-immena of line 6/7 was one the third of three kings who had ‘surrounded’ him.

As Elynn Gorris (referenced below, 2020, at p. 25) observed, there are two possibilities here: the Humban-immena of line 6/7 was either:

-

✴an otherwise-unknown late Middle Elamite king; or

-

✴the father of Shutruk-Nahhunte II (as in line 1), whom she argued was not a king but rather simply a brother-in-law of the Neo-Elamite King Humban-nikash, whom:

-

“... Shutruk-Nahhunte II would have added ... to the lineage of the last Middle Elamite kings [in order] to reinforce his legal claim to the Elamite throne.

However, as Jan Tavernier (referenced below, 2011, at p. 344, note on lines 5-7) pointed out, we know very little about the history of Elam during the substantial hiatus between Silhnahamru-Lagamar (ca. 1100 BC) and Humban-immena, the father of Shutruk-Nahhunte II (ca. 740 BC). Thus we cannot know:

-

✴whether the Humban-immena of line 1 (the father of Shutruk-Nahhunte II) had (or at least had claimed) a royal title before he married the sister of King Huban-immena; and/or

-

✴whether the Humban-immena of line 6/7 was:

-

•the last king of the Shutrukid dynasty; or

-

•the same man as the Humban-immena of line 1, the father of Shutruk-Nahhunte II.

Thus, the identity of the Humban-immena of line 6/7 must remain uncertain. Having said that, we can certainly agree with the final observation of Jan Taverner (as above): on any reading of the inscription, it indicates that:

-

“... Shutruk-Nahhunte II wanted to establish a connection with the Shutrukid dynasty, [and] not only by the choice of his throne-name.”

Shutruk-Nahhunte II and EKI 71-3: Conclusions

Jan Tavernier (referenced below, 2004, at p. 7 and p. 16) observed and Elynn Gorris (referenced below, 2020, at p. 32) supported a possible solution to the ‘Shutur/Shutruk’ problem that had been previously suggested by Walther Hinz (referenced below, at pp. 116-7):

-

✴the real name of the king [of EKI 71-73] was Shutur-Nahhunte; but

-

✴he adopted the name of Shutruk-Nahhunte I in order to link himself with this great Middle-Elamite king.

This hypothesis is supported by the facts that Shutur/Shutruk-Nahhunte II:

-

✴adopted not only the name but also the titulary of Shutruk-Nahhunte I; and

-

✴associated himself in EKI 72 with at least two other Shutrukid kings, Hutelutush-Insusinak and Silhnahamru-Lagamar.

It is possible that he sought these Shutrukid credentials to justify the fact that, as he acknowledged in EKI 72, he had seized the Elamite throne after the death of his maternal uncle, Huban-nikash.

The key question for our present purpose is whether Shutruk-Nahhunte II’s title of king of Anshan and Susa (evidenced in EKI 71 and EKI 73a) was meaningful in any political sense or purely ceremonial. In other words, how likely is it that Anshanites themselves regarded Shutruk-Nahhunte II as their king at any point in his reign? The problems are that:

-

✴although Shilhak-Inshushinak (1150-1120 BC) was the last Elamite king known to have used this title ‘king of Anshan and Susa’ before Shutruk-Nahhunte II, we cannot rule out the possibility that Anshan had returned to the Elamite fold before or during the reign of Huban-nikash and that Shutruk-Nahhunte II took the title directly from him;

-

✴as Matt Waters (referenced below, at p. 17) pointed out, Shutruk-Nahhunte II’s father, Huban-immena, could have been a local ruler of part of the kingdom (subservient to Huban-nikash), so we also cannot rule out the possibility that Shutruk-Nahhunte II acquired the kingship of Anshan directly from him; and

-

✴as we shall see, the earliest indication that the Anshanites were not directly ruled from Elam in the late 7th century BC dates to 691 BC.

However, it seems to me that the Elamites’ direct control over Anshan had probably ended long before the late 7th century BC, and that sunkik Anzan-Shushunka was merely a ceremonial (or, perhaps, an aspirational) title that Shutruk-Nahhunte II took (along with others) from Shutruk-Nahhunte I.

Shutruk-Nahhunte II and King Sennacherib of Assyria (705-681 BC)

Rather ominously, Sennacherib recorded that:

-

“At the beginning of my kingship, ... Marduk-apla-iddina (II) (Merodach-baladan), king of Kardun[iash (Babylonia), an ev]il [foe] (and) a rebel, .... sought [frie]ndship with Shutruk-Nahhunte II (Shutur-Naḫundu), an E[lamite], by presenting him with gold, silver, (and) precious stones; then, he continuously requested reinforcements”, (RINAP 3, 1: 5-7).

By 703 BC, Sennacherib was in control of Babylon, Marduk-apla-iddina (who has seized the Babylonian throne in 722 BC) was hiding in the Babylonian marshes and Shutruk-Nahhunte, whose army had fought on the losing side, must have viewed the future with some trepidation particularly when, in 700 BC, Sennacherib designated his son, Ashur-nadin-shumi, as king of Babylon (see, for example, RINAP 3, 17: 13-17).

In fact, Sennacherib contented himself by annexing the northern part of Ellipi, on the Elamites’ northern border. However, Matt Waters (referenced below, at p. 24) suggested that Shutruk-Nahhunte’s failure to halt the incursions of Sennacherib in 703-700 BC might have cost him his throne: the Babylonian Chronicles recorded that, in 699 BC:

-

“Shutruk-Nahhunte II (Shutur-Nahhunte), king of Elam, was seized by his brother, Hallutush-Inshushinak (Hallushu-Inshushinak), who shot the door in his face. He had ruled Elam for 18 years”, (ABC 1, ii: 32-35)

Hallutush-Inshushinak I (699 - 693 BC)

According to the Babylonian Chronicles, in the 6th year of the reign of Ashur-nadin-shumi , the son of Sennacherib, (i.e., in 694 BC):

-

“... Sennacherib went down to Elam and ravaged and plundered Nagitum, Hilmu, Pillatum, and Huppapanu. Afterwards, Hallustush-Inshushinak I (Hallushu-Inshushinak), king of Elam, [retaliated by marching] to Akkad. He entered Sippar ... (and) slaughtered its inhabitants. Ashur-nadin-shumi was taken prisoner and transported to Elam, (having) ruled Babylon for 6 years. The king of Elam put Nergal-ushezib on the throne in Babylon (and) effected an Assyrian retreat”, (ABC 1, ii: 36-45)

Although various versions of these events appear in Sennacherib’s annals, this version is broadly confirmed in the so-called Nebi-Unis Inscription (transliterated and translated by Daniel Luckenbill, referenced below, at pp. 88-9; note that the Assyrian name for Nergal-ushezib is Shuzubu. For the shorter, ‘sanitised version, see for example, RINAP 3, 22: iv: 32-46). Thus, it seems that Hallutash-Inshushinak was able to respond to Sennacherib’s attack on Elamite territory by:

-

✴invading Babylon:

-

✴removing Sennacherib’s son from the throne and taking him to Elam (where he was probably killed); and

-

✴placing his own man, Nergal-ushezib, on the throne of Babylon.

Sennacherib clearly could not allow Nergal-ushezib to remain in the Babylonian throne: the Babylonian Chronicles recorded that:

-

“Nergal-ushezib did battle against the army of Assyria in the district of Nippur... : he was taken prisoner in the battlefield and transported to Assyria. He had ruled Babylon ... (for) precisely six months, (ABC 1, iii: 3-6).

The next entry recorded that

-

“... the subjects of Hallutash-Inshushinak I (Hallushu-Inshushinak), king of Elam, rebelled against him ... (and) killed him, after he had ruled Elam for 6 years”, (ABC 1, iii: 6-8).

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that this coup had been prompted by fear that Hallutash-Inshushinak had, in effect, invited further Assyrian aggression.

Before discussing the aftermath of this rebellion, we should note that a king named as Hallutash-Inshushinak is mentioned on an Elamite text (EKI 77) on bricks that were used to restore the sanctuary of Ishushinak on the Acrople of Susa. However, Jan Tavernier (referenced below, 2014, at p. 61) established that:

-

“Although it was formerly believed that the king [of EKI 77 ...] was one and the same person as the king who reigned from 699 to 693 BC, it is now accepted that [the king commemorated in EKI 77 was] later king who must be situated at the end of the 7th or the beginning of the 6th century BC.”

I discuss this matter further in the following page.

Kutur-Nahhunte (693-692 BC)

The Babylonian Chronicles recorded that, after the deposition of Hallutush-Inshushinak:

-

“Kutur-Nahhunte (Kudur-Nahhunte ) ascended the throne in Elam. Afterwards, Sennacherib went down to Elam. From Raši to Bit-Burnaki, he ravaged and plundered it. [The pro-Elamite] Mushezib-Marduk ascended the throne in Babylon. [Shortly thereafter], Kutur-Nahhunte (Kudur-Nahhunte ), king of Elam, was taken prisoner in a rebellion and killed [when he had] ruled Elam for 10 months”, (ABC 1, iii: 12-15).

Sennacherib gave a slightly longer version of these events:

-

“Kutur-Nahhunte (Kudur-Nahundu), the Elamite, heard about the conquest of his cities and fear fell upon him. He brought (the people of) the rest of his cities into fortresses. He abandoned the city of Madaktu, his royal city, and took the road to the city Haydala (Hidalu), which is in the distant mountains. I ordered the march to the city Madaktu, his royal city. ... [However], I was afraid of the rain and snow in the gorges, the outflows of the mountains, (so) I turned around and took the road to Nineveh. At that time, by the command of [the gods], Kutur-Nahhunte (Kudur-Naḫundu, the king of the land Elam, did not last three months (before) suddenly died a premature death”, (RINAP 3, iv:81 - v:14).

From this account, we learn that, at least in the early 7th century century BC, Madaktu was effectively the capital of Elam and Hidalu (which was ‘in the distant mountains’) was the refuge of choice when Madaktu was threatened.

Huban-menanu (692 - 689 BC)

The Babylonian Chronicles (ABC1, iii: 15-26) recorded that:

-

✴[In 692 BC], Huban-menanu (Humban-nimena) ascended the throne of Elam.

-

✴In an unknown year, [he] mustered the troops of Elam and Akkad and fought against Assyria in Halule. He effected an Assyrian retreat.

-

✴[In 689 BC], he was stricken by paralysis and ... could not speak.

-

✴I[n 692 BC] Babylon was captured (and) Mushezib-Marduk was taken prisoner and transported to Assyria, having ruled Babylon for 4 years.

-

✴[Shortly thereafter], Huban-menanu (Humban-nimena), king of Elam, died, having ruled Elam for 4 years.

The annals of Sennacherib provides more details of these events, starting with the information that:

-

✴Huban-menanu was apparently the younger brother of Kutur-Nahhunte (RINAP 3, 22: v: 14); and

-

✴the engagement between the Assyrians and the Elamite/Babylonian coalition at Halule took place in 691 BC.

Battle at Halule (691 BC)

More specifically, Sennacherib recorded that, at that time, Huban-menanu:

-

“... whose cities I [Sennacherib] had conquered and ruined in my earlier campaign in the land of Elam. ... [On receiving this] bribe, [Huban-menanu] assembled his army ... The [highlanders] of Parsuash, Anzan (Anshan), Pasheru [and] Ellipi, [together with lowland Chaldeans, Arameans and Babylonians], a large host, formed a confederation with him. In their multitude, they took the road to Akkad and, as they were advancing towards Babylon, they met up with Shuzubu (Mušshēzib-Marduk), a Chaldean (who is) the king of Babylon, and banded their forces together.... They drew up in battle lines to confront me at the city Halule, which is on the bank of the Tigris ...”, (RINAP 3, 23: v: 29-47).

We later read that, in the battle:

-

“I [Sennacherib] quickly slaughtered and defeated Huban-undasha (Humban-undasha), nāgiru of the king of Elam, chief commander of the armies of Elam ...”, (RINAP 3, 23: v: 71 - see the translation by Wouter Henkelman, 2008, at p. 21, note 35).

Although the Babylonians claimed victory on this occasion, subsequent accounts indicate that this was a somewhat premature claim (as we shall see).

The Assyrian account of these events is important for our present purposes because of the mention of the Anshanites as allies (rather than subjects) of Elam. Matt Waters (referenced below) argued that:

-

✴it seems that Huban-menanu himself had formed the anti-Assyrian alliance (see p. 34); and

-

✴the inclusion of Parsuash and Anshan among the allies:

-

“... suggests Huban-menanu’s ability to command contingents from that region ..., [which, in turn] demonstrates some levels of Elamite political influence in Fars in the early 7th century” (see p. 35).

Kiumars Alizadeh (referenced below, at p. 28) agreed with these general observations, although he did not accept that Water’s assertion that Parsuash was in Fars: rather, he argued (at p. 29) that:

-

“... it would be better to search for Parsuash ... in the central Zagros region and not necessarily in the south and at the border of Anshan.”

The key point for the present discussion is that, while Huban-menanu could call on the Anshanites for men to fight under his field-commander Huban-undasha at Halule, it is entirely possible that the man who sent (and possibly led) the Anshanite contingent was recognised as ‘king of Anshan’.

Fall of Babylon (689 BC)

As we have seen, the Babylonian Chronicles recorded that:

-

“The 4th year of [the reign of ] Mushezib-Marduk (689 BC), ... Huban-menanu (Humban-nimena), king of Elam, was stricken by paralysis ... :

-

✴[Shortly thereafter], the city of Babylon was captured. Mushezib-Marduk was taken prisoner and transported to Assyria. Mushezib-Marduk had ruled Babylon for 4 year.

-

✴[Later that year], Huban-menanu (Humban-nimena), king of Elam, died, ... [having] ruled Elam for 4 years”, (ABC 1, iii: 19-26).”

We can supplement this account using the so-caller ‘Bavian Inscription’ of Sennacherib (transliterated and translated by Daniel Luckenbill, referenced below, at pp. 78-85). In this text, Sennacherib described two successive campaigns, the first of which (at paragraphs 34-43, at pp. 82-3) was at Halule (as above). In his ‘second campaign’ (at paragraphs 43-54, at pp. 83-4), he described what he claimed had been his complete destruction of Babylon, noting that:

-

“Shuzubu (Mushezib-Marduk), king of Babylon, together with his wife and nobles, I carried off alive to my land”, (paragraph 46, at p. 83).

Thus, it seems that, within two years of the stand-off at Halule:

-

✴Sennacherib had sacked Babylon and captured Mushezib-Marduk; and

-

✴Huban-menanu had died (apparently of natural causes).

In other words, in that short space of time, the political climate at Elam had been transformed (and not for the better).

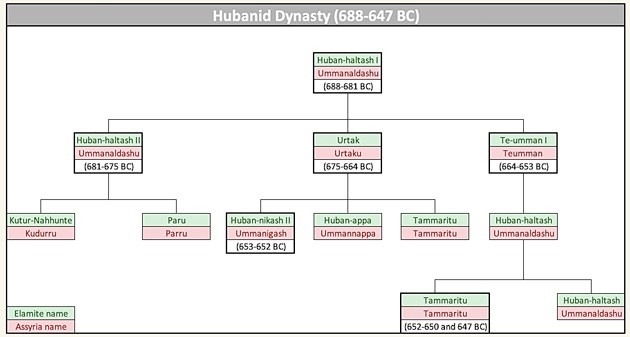

Hubanid Dynasty (688 - 650 BC)

Data from Elynn Gorris (referenced below, 2021)

Elynn Gorris (referenced below, 2021, at p. 1) argued that:

-

✴Huban-menanu was the last Shutrukid king; and

-

✴the next Elamite king, Huban-Haltash I (Humban-haltash - see ABC 1, iii: 27), was the first of the so-called Hubanid dynasty.

In 680 BC:

-

✴Huban-haltash I died and was succeeded by his son (who ruled as Huban-Haltash II); and

-

✴shortly thereafter, Sennacherib died and was succeeded by his son, Esarhaddon (see ABC 1, iii: 30-38).

In 675 BC, Huban-Haltash II died and was succeeded by his brother Urtak (see ABC1, iv: 13).

King Urtak (675 -664 BC)

The Assyrian annals recorded that, in 673 BC:

-

“The Elamites (and) Gutians, obstinate rulers, who used to answer the kings, my ancestors, with hostility, heard of what the might of the god Ashur, my lord, had done among all of (my) enemies, and fear and terror poured over them. So that there would be no trespassing on the borders of their countries, they sent their messengers (with messages) of friendship and peace to Nineveh, before me, and they swore an oath by the great gods”, (‘Esarhaddon, Prism A’, v: 26-33).

This agreement led to almost a decade of peace in the region. In 672 BC, Esarhaddon named:

-

✴one of his sons, Ashurbanipal, as the crown prince of Assyria; and

-

✴another, Shamash-shum-ukin, as the crown prince designate of Babylon.

These arrangements duly came to fruition: when Esarhaddon died in 669 BC:

-

✴Ahurbanipal became king of Assyria: and

-

✴Shamash-shum-ukin, now his vassal, became king of Babylon.

As Matt Waters (referenced below, at pp. 45-7) observed, Urtak retained good relations with Ashurbanipal until 664 BC, when Ashurbanipal recorded that:

-

“On my sixth campaign, I marched against Urtak (Urtaku), the king of the land Elam who neither remembered the kindness of [my] father (nor) respected my friendship”, (‘Ashurbanipal, Prism B’, iv: 15-18)”.

Ashurbanipal then recorded (at lines iv: 43-60) that the rebels fled when his army approached, after which, the gods claimed the lives of Urtak himself and two of the other rebel leaders:

-

“Within one year, they (all) laid down (their) live(s) at the same time. ... [The Elamites] overthrew [Urtak’s] royal dynasty. They made somebody else assume dominion over the land Elam. Afterwards, Te-umman (Teumman), [an inveterate] demon, sat on the throne of Urtak (Urtaku)”, (‘Ashurbanipal, Prism B’, iv: 61-69)”.

In fact, as Elynn Gorris (referenced below, 2021, at p. 4) observed, Te-umman (a short form of Tepti-Huban-Inshushinak) was Urtak’s younger brother.

Ashurbanipal recorded that, once in power, Te-umman:

-

“... constantly sought out evil (ways) to kill:

-

✴Huban-nikash (Ummanigash), Huban-appa (Ummanappa), (and) Tammarītu, the sons of Urtaku, the king of the land Elam; and

-

✴Kudurru (and) Parrû, the sons of Huban-haltash II (Ummanaldashu), the king who came before Urtaku.

-

[They], together with 60 members of the royal (family), countless archers, (and) nobles of the land Elam fled to me from Te-umman’s slaughtering and grasped the feet of my royal majesty””, (‘Ashurbanipal, Prism B’, iv: 69-79)”.

Matt Waters (referenced below, at p. 47) observed that a record in the Babylonian Chronicles (ABC 15: 3) that an Elamite prince fled to Assyria in 664 BC probably referred to the future Huban-nikash II (see below). As Elynn Gorris (referenced below, 2020, at p. 41) observed, these ‘defections’ indicate:

-

“... a deep internal impasse that divided the Elamite court into two factions ...”

King Te-umman (ca. 664-653 BC)

We know of only a single event in the reign of Te-umman: Ashurbanipal recorded that:

-

“On my seventh campaign, I marched against Te-umman (Teumman), the king of the land Elam, who had regularly sent his envoys to me concerning [his five nephews], ... (and asking me also) to send (back) those (other) people who had fled to me and grasped my feet. I did not grant him their extradition”, (‘Ashurbanipal, Prism B’, iv: 80-88).

This campaign culminated in his famous victory in a battle inside the city of Tīl-Tuba on the Ulaya River in the plain of Susa (line v: 90), and then then recorded that:

-

“In the midst of his troops, I cut off the head of Te-umman (Teumman), the king of the land Elam”, (‘Ashurbanipal, Prism B’, v: 93).

Ashurbanipal referred to an eclipse of the moon before the battle (line v: 6), allowing these events to be dated to 653 BC: if this is correct, then Te-umman had avoided conflict with Ashurbanipal for almost a decade prior to this war.

Ashurbanipal then embarked on a campaign against Dunanu, the leader of the Aramean tribe of Gambulu, who had rebelled against Ashurbanipal as allies of Te-umman. He claimed a complete victory, after which he captured Dananu and his brothers and took them to Nineveh. where:

-

“I h]ung

-

✴[the hea]d of [Teu]mman, the king of the land Ela[m, around the neck of Dunānu]. [and]

-

✴[the head of Ishtar-Nandi (Shutur-Nahundi) around the neck of S]amgunu, [the second brother of Dunānu, (‘Ashurbanipal, Prism C’, vii: 47-50).

We learn from three surviving texts in the so-called ‘Te-umman and Dunanu cycle’ of epigraphs (see Joshua Jeffers and Jamie Novotny, referenced below: entries: 161: i: 6-7, at p. 173; 162: 10-11, at p. 179; and 163: 5-6, at pp. 180-1) that the unfortunate Ishtar-Nandi had been ‘the king of the land of Hidalu’.

Huban-nikash II (653- 652 BC)

Ashurbanipal recorded that, after his victory at Tīl-Tūba and is execution of Te-umman:

-

“... I placed Huban-nikash (Ummanigash), who had fled to me (and) had grasped my feet, on his (Te-umman’s) throne. I installed Tammarītu, his third brother [not shown on the family tree above], as king in the city of Hidalu, [on the Babylonian border]”, (‘Ashurbanipal, Prism B’, v: 97 - vi: 2).

Thus, it seems that:

-

✴Te-umman, ‘king of Elam’ had fought and died at Tīl-Tuba alongside Ishtar-Nandi ‘the king of the land of Hidalu’; and

-

✴Ashurbanipal had replaced them by Huban-nikash II and his third brother, Tammarītu, respectively.

As Wouter Henkelman (referenced below, 2003, at pp. 254-5) observed, the existence of a ‘king of the land of Hidalu’ has been taken to indicate a political split in what had hitherto been a unified Elamite kingdom. However, he argued (at p. 255) that:

-

“As far as the limited available evidence allows any conclusions, there seems to be no grounds for assuming a split of the Elamite kingdom. Hidali was a strategically important cit and the position of its governor would obviously [reflect] this. From the case of Huban-nikash II and his brother, Tammarītu, it could be inferred that ‘king of Hidalu’ was a position [that was at least sometimes] given to a member of the ruling dynasty.”

An inscription relating to a relief in the southwestern palace at Nineveh that depicts scenes from the aftermath of his victory at Tīl-Tūba (now in the British Museum) identifies the man on the extreme left (who is being led forward by an Assyrian soldier) as:

-

“[Umman]igash, the fugitive servant who submitted to me at my command, [walking] joyfully into the midst of Madaktu and Susa. ... I sent my sutreshi, ... and he set him on the throne of Te-umman (Teumman), whom [I had] conquered”, (translation from Daniel Potts, 2016, at p. 271).

Thus, after his victory over Te-umman, Ashurbanipal installed:

-

✴Huban-nikash (Te-umman’s nephew, who had been living in exile at his court) as Huban-nikash II, king of Elam (or, at least, of Madaktu and Susa); and

-

✴Tarramitu (his younger brother, who had shared his exile) as king of the border city of Hidalu.

The key event that took place during the reign of Huban-nikash II was Babylonian rebellion (described in my page on ...): in summary, Ashurbanipal recorded that, in 652 BC, after some 17 years of apparently peaceful co-existence:

-

“... Shamash-shuma-ukīn, (my) unfaithful brother for whom I performed (many acts of) kindness (and) whom I had installed as king of Babylon [revolted against me]”, (‘Ashurbanipal, Prism A’, iii: 78).

Soon after, Ashurbanipal complained that Huban-nikash II:

-

“(As for) Huban-nikash II (Ummanigash), for whom I performed many act(s) of kindness (and) whom I installed as king of the land Elam, (and) who forgot my favour(s): he did not honour the treaty sworn by the great gods, (and) accepted bribe(s) from the hands of the messengers of Shamash-shuma-ukīn,(my) unfaithful brother, my enemy. He sent his forces with [the Babylonian rebels] to fight with my troops, my battle troops who were marching about in Karduniaš (Babylonia) (and) subduing Chaldea”, (‘Ashurbanipal, Prism B’, vi:86-vii:5).

Ashurbanipal then described the engagement that followed and its aftermath:

-

“My troops (who were stationed) in the city of Mangisi ... came up against [the Elamite/Babylonian contingents] and brought about their defeat. They cut off the heads of [their commanders] ... and brought (them) before me. I dispatched my messenger to Huban-nikash II (Ummanigash) regarding these matters, ... [but] did not reply to my word(s). ... [The gods] rendered a just verdict for me concerning Huban-nikash II (Ummanigash): Tammarītu [see below] rebelled against him and struck him, together with his family, down with the sword”, (‘Ashurbanipal, Prism B’, vii:20-31).

Thus, it seems that the military failure at Mangisi triggered yet another coup at Elam.

Tammaritu (652-650 BC)

Although it is generally agreed that this Tammaritu was a member of the Hubanid dynasty, his precise line of descent is a matter for conjecture: as we have seen, Elynn Gorris (referenced below, 2021) argued that he was a grandson of Te-umman. It seems that he was intent on continuing the Elamite backing of Shamash-shuma-ukīn, since Ashurbanipal complained that:

-

“Tammaritu, who was (even) more insolent than Huban-nikash II (Ummanigash), [now] sat on the throne of the land Elam ... [He also]:

-

✴accepted bribes;

-

✴did not inquire about the well-being of my royal majesty;

-

✴went to the aid of Shamash-shuma-ukīn, (my) unfaithful brother and

-

✴readily sent his weapons to fight with my troops.

-

As a result of the supplications that I had addressed to (the gods), ... his servants rebelled against him and together struck down my adversary: Indabibi, a servant of his who had incited rebellion against him and then sat on his throne”, (‘Ashurbanipal, Prism B’, vii: 33-43).

Ashurbanipal then magnanimously noted that:

-

“Tammarītu handed himself over to do obeisance to me and made an appeal to my lordly majesty to be his ally. ... I allowed Tammaritu (and) as many people as (were) with him to stay in my palace”, (‘Ashurbanipal, Prism B’, vii: 55-60).

The deposition of Tammaritu in 650 BC effectively marked the end of the Hubanid dynasty.

Read more:

Jeffers J, and Novotny J., “The Royal Inscriptions of Ashurbanipal (668–631 BC), Aššur-etel-ilāni (630–627 BC), and Sîn-šarra-iškun (626–612 BC), Kings of Assyria: Part 2”, (2023) University Park, PA

Gorris E. (2021), “The Hubanid Dynasty”, in:

Potts D. et al. (editors), “Encyclopedia of Ancient History: Asia and Africa”, (2021) 7 pages

Gorris E., “Power and Politics in the Neo-Elamite Kingdom: Volume 60 (Acta Iranica)”, Les Études Classiques, (2020) Leuven, Paris and Bristol CT

Alizadeh K., “The Earliest Persians in Iran: Toponyms and Persian Ethnicity”, Digital Archive of Brief Notes and Iran Review (DABIR), 7 (2020) 16-53

Tavernier J. M., “What's in a name?: Hallushu, Hallutash or Hallutush”, Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archéologie Orientale, 108:1 (2014) 61-6

Tavernier J. M., “Élamite Analyse Grammaticale et Lecture de Textes”, Res Antiquae, 8 (2011) 315-50

Henkelman, W. F. M., “The Other Gods Who Are: Studies in Elamite-Iranian Acculturation Based on the Persepolis Fortification Tablets”, (2008) Leiden

Tavernier J. M., “Some Thoughts on Neo-Elamite Chronology”, ARTA (Achaemenid Research on Texts and Archaeology), 3 (2004) 1-44

Henkelman, W. F. M., “Defining Neo-Elamite History: [Review of Waters (2000) below]”, Bibliotheca Orientalis, 60:3-4 (2003) 251-63

Waters M. W., “A Survey of Neo-Elamite History”, (2000) Helsinki

Malbran-Labat F., “Les Inscriptions Royales de Suse: Briques de l'Époque Paléo-Élamite à l'Empire Néo-Élamite”, (1995) Paris

Grayson A, K., “The Walters Art Gallery Sennacherib Inscription”, Archiv für Orientforschung, 20 (1963), 83-96

Hinz W., “Das Reich Elam (Urban-Bücher 82)”, (1964) Stuttgart

Luckenbill D. D., “Annals of Sennacherib”, (1924) Chicago IL

Foreign Wars (3rd century BC)

Home