Puzur-Inshushinak at Susa

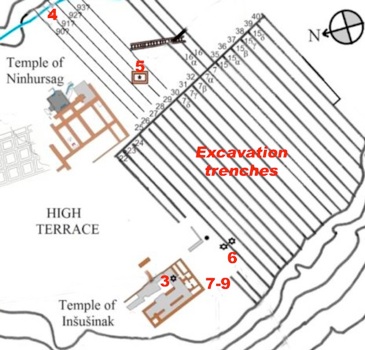

Plan of the southern part of the Acropole at Susa

Adapted from Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below, 2018, Plate 2, at p. 208): my additions in red.

Numbers = those used in this plate for objects relating to Puzur-Inshushinak found during the excavations of 1903-4,

all of which are discussed below

As noted on the previous page (and as discussed further below), Puzur-Inshuhinak was the 12th and last king recorded in the so-called Awan King List (AwKL). Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 191), he was:

-

“... a native Iranian, a proof of which is the Elamite name of his father, [Shimpi-ishuk, who is named in some of his inscriptions].”

All we really know about his route to power in Elam is that, since his father did not appear in the AwKL, it is unlikely that this involved dynastic succession. However, Steinkeller (as above) argued that:

-

“As far as can be determined, [he] began his career as a ruler of Susa. This is confirmed by the extensive body of monuments and inscriptions that he has left there.”

Fortunately, as Daniel Potts (referenced below, 2016, at p. 113) pointed out:

-

“An Old Babylonian copy of an inscription of Ur-Namma, the founder of the Third Dynasty of Ur, [which was found at Isin, names Puzur-Inshushinak ... as one of his adversaries. Thus, we can confidently date Puzur-Inshushinak to ca. 2100 BC.”

I shall discuss this inscription further below, in the context of the final stage in Puzur-Inshushinak’s career. For the moment, we should simply note that this dating places his career at the end of the century or so in which Susa enjoyed independence from Mesopotamian hegemony:

-

✴this period started when Susa threw off the hegemony of the kings of Akkad, probably in the reign of the fifth of them, Shar-kali-sharri (the great grandson of Sargon) in ca. 2200 BC; and

-

✴it almost certainly ended with Puzur-Inshushinak’s defeat at the hands of Ur-Namma, the first of the so-called ‘Ur III kings’.

The reconstruction of Puzur-Inshushinak’s career relies almost entirely on the aforementioned ‘extensive body of his monuments and inscriptions’, most of which were found on the so-called Acropole at Susa by French archeologists in the early 20th century and are now in the Musée du Louvre. For example, Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 123) observed that:

-

“In his 12 extant inscriptions, he bears different titles:

-

✴puzur4-dinshushinak ensi2 shushinki

-

(Puzur-Inshushinak, governor of Susa);

-

✴puzur4-dinshushinak ensi2 shushinki, [shakkanakku = shagina] ma-ti elamki, dumu shi-im-pi2-ish-hu-uk

-

(Puzur-Inshushinak, governor of Susa, general of the land of Elam, son of Shimpi-ishuk); and

-

✴puzur4-dinshushinak, da-num2 LUGAL a!-wa-anki, dumu shi-im-pi2-ish-hu-uk

-

(Puzur-Inshushinak, the mighty king of Awan, son of Shimpi-ishuk).

-

[These] changes ... reflect the chronology of his cursus honorum: i.e., his rise from local ruler of Susa to overlord of Elam and beyond (da-num2 LUGAL a!-wa-anki).

These titles were not new at Susa: as discussed on the previous page:

-

✴Eshpum, who was the Akkadian governor at Susa in the reign of Manishtushu, described himself as ensi of Susa in the inscription on a votive statue (see below); and

-

✴Epir-mupi, who was probably a later governor in the period in which Akkad was under pressure from the Gutians. is recorded as :

-

•ensi of Susa in an administrative document ;

-

•shakkanakku of the land on Elam on his cylinder seal; and

-

•da-num (mighty) on the seals of two of his servants.

As Daniel Potts (referenced below, 2021, at p. 1) pointed out:

-

“By the time of Puzur-Inshushinak, ... the Kingdom of Akkad and ... [its] hold over Susa and other parts of southwestern Iran [were obviously] no more. Nevertheless, Puzur-Inshushinak may have adopted these familiar titles because they conferred [on him] a measure of legitimacy”.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 191) argued that, at some point in his career, Epir-mupi must have achieved independence from Akkad, as evidenced by his uses of the title of ‘da-num’, which had first been used by the powerful Akkadian king Naram-Sin (the father and predecessor of Shar-kali-sharri). As we shall see, Puzur-Inshushinak’s use of this title, which has so far only been found on a few limestone steps that belonged to one or more monumental staircases, probably belongs to the last phase of his career (in which he substantially extended his territory, only to lose it at the hands of Ur-Namma). I will discuss these ‘da-num’ inscriptions later in this page, in the context of Puzur-Inshushinak’s later career. For the moment, I will concentrate of his rule as governor of Susa and general of the land of Elam.

Earliest Inscriptions of Puzur-Inshushinak

G&K: Gelb and Keinast (referenced below, Elam 1-13); A-M: J. Álvarez-Mon (referenced below, 2018, entries §1-§12);

P: Daniel Potts (referenced below, 2016, Table 4.12. left column: Louvre Sb: museum number

Akk = Akkadian cuneiform; LE= Linear Elamite (identifying letters from F. Desset, referenced below, 2022, pp. 16-7)

At least 3** foundation nails from the Temple of Shugu: SB. 12728, 18457 and 21889

Blue boxes: Puzur-Inshushinak has the title governor of Susa in these three inscriptions: his title in all the

other inscriptions in this table is (or is probably) governor of Susa and general of the land of Elam

Pink boxes: see below

The table above identifies all of surviving objects that carry Akkadian inscriptions of Puzur-Inshushinak except those that belong to the monumental staircase(s) mentioned above:

-

✴in the inscriptions on three of them (in blue boxes above), he is described as ensi of Susa (tout court); and

-

✴in the other 13, he is described (or probably described) as ensi of Susa and shakkanakku of the land on Elam.

The relationship between the four objects in pink boxes is slightly complicated:

-

✴one of them, the votive tablet with lion head (Sb 17, illustrated below), carries a complete Akkadian inscription that:

-

•explicitly designates Puzur-Inshushinak as governor of Susa, general of the land of Elam; and

-

•ends with a distinctive curse formula (translated below);

-

✴another two:

-

•the votive boulder with snake, lion and foundation scene (Sb. 6+177+18446}; and

-

•a fragmentary statue of Puzur-Inshushinak (Sb. 87);

-

carry Akkadian inscriptions that are broken at the beginning but can be associated with Sb. 17 because they end with what seems to be the same curse formula; and

-

✴the entry for the fragmentary votive boulder with snake (Sb. 172) is in italics because:

-

•it does not (in its present state) carry an Akkadian inscription; and

-

•its Linear Elamite inscription (LE text D) does not apparently name Puzur-Inshushinak (see François Desset (referenced below, 2012, at p. 113); but

-

it is so similar in terms of its iconography to Sb. 6+177+18446 that we might reasonably assume that it belongs in this group of inscriptions.

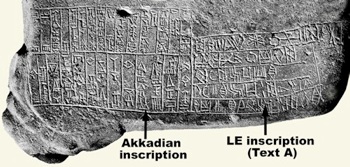

Akkadian Cuneiform and Linear Elamite

Detail of votive tablet Sb. 17, showing the complete Akkadian and LE inscriptions on the upper surface

Adapted from an image from museum website (my black text)

At least 7 of the objects included in the table above are , from the linguistic point of view, ‘bilingual’. The most important of them in this respect is the votive tablet with a lion head (Sb. 17, discussed in more detail below), because both of its inscriptions are complete. The Akkadian inscription has been translated as follows:

-

“To Inshushinak, his Lord: Puzur-Inshushinak, governor of Susa, general of the land of Elam, son of Shimpi-ishuk, has dedicated [an object] of copper and cedar. Whoever erases this inscription, may Inshushinak, Inanna, Narundi (and) Nergal tear out his roots and destroy his descendants. Support this house, such is the name of the gate (?)”, (based on the translations by Javier Álvarez-Mon, referenced below, 2018, at entry 7, p. 183, and François Desset, referenced below, 2012, at p. 113).

Puzur-Inshushinak’s Use of Akkadian

The fact that these and all the other objects in the table (with the possible exception of Sb. 172) carry Akkadian inscriptions is unsurprising: as Florence Malbran-Labat (referenced below, 2021, at pp. 1316-7) observed:

-

“In the current state of our knowledge, [Akkadian] was ... the main written language in Elam until the mid-2nd millennium BC. It was the language of the conquerors, when the Sumero-Akkadian kings captured Susiana and installed garrisons and administrative services there ... [and], above all, the language of Susiana, from where most of the [known Elamite] documents in Akkadian come from ...”

Since, as we shall see, the decipherment of Linear Elamite is still at a relatively early stage, most of the useful information that can be derived from Puzur-Inshushinak’s inscriptions comes from those written in Akkadian cuneiform.

Puzur-Inshushinak’s Use of Linear Elamite

Probable original locations of known LE inscriptions

Adapted from François Desset et al. (referenced below, 2022, Figure 1, at p. 12)

As François Desset et al. (referenced below, 2022, at p. 11) pointed out:

-

“In 1903, French excavators working in the Acropolis mound of Susa found inscriptions attesting to a new writing system. ”

These discoveries were published by Vincent Scheil (referenced below, 1905, MDP 4), Initially, this ‘new writing system’ was assumed to be a more developed form of Proto-Elamite writing , and it was only in 1962 that it became clear that it was, in fact, unrelated to any other known script. It was at this point that Walther Hinz (referenced below) dubbed this ‘new’ script ‘elamische Strichschrift’, which was then rendered into English as Linear Elamite (hereafter LE).

The corpus of known LE texts increased over time, so that, when, in 1989, Beatrice André and Mirjo Salvini (referenced below, at pp. 59-62) published two LE inscriptions (texts T and U) that they had discovered in the Musée du Louvre, this took the known corpus up to 21 texts. Thereafter, François Desset (referenced below, 2012, Figure 29, at p. 92) was able to list 30 of them, 24 of which came from known locations:

-

✴1 was thought to have come from the vicinity of Persepolis;

-

✴1 came from Shahdad;

-

✴4 came from Konar Sandal; and

-

✴18 came from Susa, including 10 (A, B, C, E, F, G, H, I, P and U) that were on objects that were certainly associated with Puzur Inshushinak.

It is therefore unsurprising that attempts to decipher the new script concentrated on the ‘Puzur-Inshushinnak’ inscriptions, particular since (as we have seen) almost all of them were on ‘bilingual’ objects. However, as François Desset et al. (referenced below, 2022, at p. 24) observed:

-

“Unfortunately, the LE texts [on these objects] never translate the cuneiform inscriptions (or vice versa); the two sets of texts just share some proper nouns and some titles that can be considered to be identical or equivalent.”

For this reason, as François Desset (referenced below, 2012, at p. 105) pointed out, the LE text A (on the so-called ‘lion tablet’, illustrated above) emerged as the most promising document for the decipherment of the new script, since:

-

✴both of the inscriptions on the tablet are clearly complete; and

-

✴more importantly, the Akkadian text includes a relatively large number of proper nouns (including Inshushinak, Puzur-Inshushinak, Susa, and Simb/pishuk, Inana/Ishtar, Narude and Nergal), at least some of which might be expected to appear also in the LE text.

Nevertheless, the lack of other suitable texts impeded progress and, as François Desset et al. (referenced below, 2022, at p. 12), observed:

-

“All in all, before 2018, [only 12 LE] signs were properly identified: hu, k, k₂, na, pi, pu, ri₂, ru, she, shi, za and zu. “

In 2018, François Desset (referenced below, 2018b) published a group of 8 silver beakers from private collections (7 from the Mahboubian collection and the 8th from the Schøyen collection) that were inscribed with LE inscriptions (LE texts X, Y, Z, F′, H′, I′, J′, and K′). According to François Desset et al. (referenced below, 2022, at p. 13), these beakers :

-

“... may come from a Shimashki/Sukkalmaḫ-related royal graveyard located in the Kam-Firuz area (Fars), some 40 km north of Tal-i Malyan, the ancient city of Anshan. ... Since the names of the Sukkalmah rulers Eparti II and Shilhaha, as well as that of the god Napiresha, could be recognised in these texts, this group of inscriptions became the key for the decipherment of Linear Elamite, enabling [scholars] ... to decipher more than 30 new signs. ”

This allowed Desset and his colleagues to publish (in their Appendix at pp. 55-7) complete transliterations of a group of 3 very similar inscriptions (F-H), each of which was on a step from the monumental staircase(s) mentioned above , together with a composite translation.and discussed further below) of Puzur-Inshushinak (see below). Open access editions of all the known LE inscriptions are apparently forthcoming (see p. 16), which means that we may soon learn more about the corpus of Puzur-Inshushinak’s inscriptions at Susa.

This brings us back to the question of Puzur-Inshushinak’s role in the emergence of LE in ‘royal’ inscriptions in the region. The first thing to consider is where his LE inscriptions fit chronologically within the LE corpus. As François Desset (referenced below, 2018a, referenced below, at pp. 397-8) observed, while we can date his own LE texts (A, B, C, E, F, G, H, I, P and U) to ca. 2100 BC:

-

“... nothing necessarily associates the other [texts in the current corpus] to [his] epoch ... [Indeed]:

-

✴the texts found in Shahdad and Konar Sandal (S, B’, C’, D’ and E’) come from archaeological contexts dated to the second half of the 3rd millennium BC; [and]

-

✴... [at least three of] the silver vessels with LE inscriptions [in the Mahboubian collection (X, Y and Z))] might be dated to the end of the 3rd and the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC.

-

[Thus], the data currently available ... show that this writing system was used at least between 2500 and 1800] BC.

In other words:

-

✴LE was already established in the Elamite highlands and in the neighbouring Marhashi region before Puzur-Inshushinak introduced it at Susa; and

-

✴it continued to be used in the subsequent Shimashki and Sukkalmah periods (discussed in the following page).

We should also consider the related geographical perspective: Puzur-Inshushinak placed a writing system that was already established in the Elamite highlands and used it (alongside the writing system of the Akkadians) at Susa, on the border of Mesopotamia. This decision is usually assumed to have been ‘political’: for example:

-

✴Florence Malbran-Labat (referenced below, 2018, at p. 466) saw as part of:

-

“... a program that was probably nationalist ...”; and

-

✴Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, at p. 170) characterised LE as:

-

“... the presumed ‘national’ language of the Awanite kingdom.”

More specifically, it seems to me that Puzur-Inshushiank probably wished to associate his rule at Susa with both:

-

✴the grandeur of the Akkadian past; and

-

✴the ‘brave new world’ of the now-independent Elamite highlands.

Puzur-Inshushinak, Ensi of Susa

Statue of a seated goddess from Susa, now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 54 + Sb 6617)

Image on the left from Beatrice André-Salvini (referenced below, at p. 91)

Image on right: detail of the lion reliefs on the back of the throne

According to Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, entry entry §5, at pp. 180-2) the head and the body of this limestone statue were found (in 1904 and 1907 respectively) in a small shrine on the Acropole, that had been excavated in trench 93, to the south of the temple of Ninhursag (location 5 in the plan above). As Beatrice André-Salvini (referenced below, at p. 90) observed:

-

“This cult statue ... is executed in Mesopotamian style. The Susian goddess is depicted with the characteristic features of the great Mesopotamian goddess Inanna/Ishtar and is associated with lions, Ishtar's animal attribute. She wears the distinctive clothing of deities: a flounced garment of lambswool and a headdress with horns over the hair, which is gathered in a chignon at the nape of the neck. The face, which is crudely carved, was originally plated (probably with gold), as rivet holes attest. The eyes must have had shell and lapis lazuli inlays that were embedded in bitumen. The goddess holds a goblet and a palm leaf against her chest. The backless throne has six lions sculpted in bas- relief:

-

✴two sit on either side of the throne;

-

✴two others hold [poles] and stand in the human posture [illustrated above] ... ; and

-

✴on the front base, under the bare feet of the goddess, two recumbent lions flank a flower [= an eight-petaled rosette: see Javier Álvarez-Mon, referenced below, 2020, at p. 150].

-

The throne bears a dual inscription written in cuneiform Akkadian and Linear Elamite.

-

✴Little remains of the inscription in Akkadian along the left edge, other than the name of the dedicator, ‘Puzur-Inshushinak, [ensi] of Susa’ ...

-

✴The Elamite inscription [= LE text I], on the right edge of the throne, gives the name of the goddess, probably Narundi or Narunte.”

Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, at p. 181) translated the Akkadian text as follows:

-

“[To Narunte, I am] Puzur-Inshushinak, ensi of Susa: Oh you (my prayer) with your ears, may you be able (to [hear]). My judgement(?), judge !”

The identification of ‘Narunte’ here was based on an early reading of LE text I, supported by the fact that:

-

✴an Akkadian ensi of Susa named Eshpum, who had governed under king Manishtushu, had presented a statue of himself as an offering to Narundi (as discussed in the previous page); and

-

✴this statue (now Sb. 82 in the Musée du Louvre) was found in the area of the Temple of Ninhursag.

We know that Narundi was an important deity at Susa even before the time of Puzur-Inshusinak, since she appears 7 times in the so-called Treaty of Naram-Sin (EKI 2: discussed below in the context of Inshushinak, who appears in it 8 times). Furthermore, she is invoked in the curse formulae of 7 of Puzur-Inshushinak’s inscriptions (including that on the votive tablet Sb. 17 that is translated above: for the whole list, see Javier Álvarez-Mon, referenced below 2018, Table III, at p. 194). Having said that:

-

✴as noted above, Beatrice André-Salvini observed (in 1992) that the goddess of Sb 54 has:

-

“... the characteristic features of the great Mesopotamian goddess Inanna/Ishtar and is associated with lions, Ishtar's animal attribute”; and

-

✴François Desset (referenced below, 2021, at p. 76) argued that this goddess, who:

-

“... was previously wrongly identified as [Narundi], was, in fact, designated in LE text I] as pe-l-ti-ka-li3-m (= Belat-ekallim), a byname traditionally reserved in Susa for Innana/Ishtar, [and] this identification is confirmed by the lions carved on the throne of the goddess and under her feet”.

Furthermore, Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2020, at p. 150) observed, when considering the relief of the an eight-petaled rosette below the goddess’ feet:

-

“One can hardly overlook the association of rosettes and lions with the Mesopotamian Innana/ Ishtar.”

We know that Narundi was not simply the name given to Inanna/Ishtar at Susa since both goddesses feature in the curse formulae on at least three of the inscribed objects in the table above (the votive tablet with lion head, the votive boulder with foundation scene and the stele Sb. 160: see Javier Álvarez-Mon, referenced below 2018, Table III, at at p. 194).

Puzur-Inshushinak and ‘his Lord, Inshushinak’

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at pp. 293-4) observed that:

-

“The origins of Puzur-Inshushinak are still obscure. Given the fact that his father’s name is Elamite, he must have been of Elamite origin. ... [If so, we must] assume that he adopted his personal name only after he had come to Susa, in recognition of the local cult of Inshushinak.”

We know that Inshushinak was already an important deity at Susa when Puzur-Inshushinak took power there because his name is prominent in the so-called ‘Treaty of Naram Sin’ (ca. 2250 BC), which was discovered at Susa in 1906-8: the relevant text was inscribed on a clay tablet that was found there (and is now in the Musée du Louvre: exhibit Sb. 8833). The museum note on this exhibit characterises its inscription as:

-

“The oldest original diplomatic document, [which] was ... written in Elamite, transcribed into Akkadian. The gods of Elam, guarantors of the treaty, are listed to begin with, [followed by] the statement:

-

‘Naram-Sin's enemy is my enemy, Naram-Sin's friend is my friend’."

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 189) drew attention to the enormous linguistic difficulties presented by this text and reproduced (at his note 22) the opinion of Friedrich König (who transliterated it as EKI 2): that a complete translation of the text is ‘nicht zu denken’ (out of the question). Thus, Steinkeller reasonably argued that the function of the ‘document’ remains unknown: all we can really say is that:

-

✴it starts with the invocation of a number of gods, the majority of whom are Elamite, including, for example, Inshushinak (dnin-szuszin), who appears at line 1:8 and on seven other occasions; and

-

✴the name of the deified Naram-Sin (na-ra-am-dsuen) appears at least ten times.

We have no evidence to suggest that Puzur-Inshushinak built or significantly restored the Temple of Inshushinak on the Acropole (which, if not the only Inshushinak temple of Susa, was probably the most important): as Florence Malbran-Labat (referenced below, 2018, at p. 466) pointed out, although he:

-

“... dedicated many monuments to his gods on the Acropolis of Susa, no foundation bricks in his name were found.”

However, we do know that Puzur-Inshushinak laid great stress on his devotion to Inshushinak: as Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below, 2018) pointed out:

-

✴5 of the 9 objects that carry inscriptions of Puzur-Inshushinak (numbers 3, 6, 7-9 on the map above) were discovered Inshushinak’s temple on the Acropole; and

-

✴8 of the 11 of Puzur-Inshushinak’s Akkadian inscriptions that mention one or more deities mention Inshushinak (see his Table III, at p. 194).

Votive Tablet with Lion Head (Sb. 17; Álvarez-Mon, §7; LE text A)

Votive tablet of Puzur-Inshushinak from Susa, now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 17): image from museum website

According to Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, entry §7, at p. 183) this limestone boulder was found in 1903, under the paving of the Inshushinak temple on the Acropole. As discussed above, it carries two complete inscriptions, one in Akkadian and another in LE. Álvarez-Mon (as above) translated the Akkadian inscription as follows:

-

“To Inshushinak, his Lord: Puzur-Inshushinak, [governor] of Susa, [general] of the land of Elam, son of [Shimpi-ishuk], has dedicated [an object] ... of copper and cedar. He who removes this inscription: may Inshushinak, Inanna, Narundi (and) Nergal tear out his root and snatch his descendants (….).”

I discuss the significance of the object of copper and cedar in more detail below.

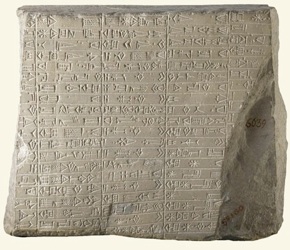

Stele of Puzur-Inshushinak (Sb. 160)

Stele of Puzur-Inshushinak from Susa, now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 160): image from the museum website

This limestone stele from Susa, which is now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 160), carries an inscription in Akkadian cuneiform that was first published in 1902 (by Vincent Scheil, referenced below, 1902, MDP 4). Unfortunately (as far as I know) the location of its discovery is now unknown. Florence Malbran-Labat (referenced below, 2018, at p. 466) referred to its inscription as:

-

“... a very unusual long dedication, [in which Puzur-Inshushinak] states the regulation of religious endowments.”

She reproduced the now-lacunose opening lines (citing Edmond Sollberger and Jean-Robert Kupper, referenced below, IRSA IIG2f):

-

“To [Inshushi]nak, his [lord, Puzur- Inshu]shinak, [the son of Shim]pi- [ish]uk, [the gover]nor [of Susa, vicer[oy] of the coun]try [of Elam, ...”

Beatrice André and Mirjo Salvini (referenced below, at p. 70, note 35, citing Vincent Scheil, referenced below, 1902, MDP 4, p. 4ss, also referenced below) included this inscription among those in which Puzur-Inshushinak is named as governor of Susa and general of the land of Elam.

Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, at p. 193) translated the rest of the inscription as follows:

-

“[…] and when he (Puzur-Inshushinak) opened the canal to/from Sidari, he:

-

✴erected a statue before the gate (bâb) of the temple (of Inshushinak); and

-

✴provided his (temple) gate with [an object] of copper and cedar.

-

A sheep at dawn and a sheep in the evening were chosen daily (for sacrifice) and singers sang all day and night at the gate of (the temple) of Inshushinak. He dedicated 20 sila of pure oil for the care of the gate ... Whoever seeks to remove these votive objects should have his roots torn out and his seeds removed by Inshushinak, Shamash, Enlil, Enki, Ishtar, Sin, Ninhursag, Narunte and the totality of the gods.”

I discuss the significance of the object of copper and cedar in more detail below.

Pierced Objects

Votive Boulder (Sb. 6 + 177; Álvarez-Mon, §8; LE text B)

Pierced boulder from the Acropole of Susa, now in the Musée du Louvre: images from museum website

Left: front view (fragment Sb. 6) Right: lower rear view (fragment Sb. 177)

Described as object 8 by Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below, 2018, at pp. 183-5)

According to Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, entry §7, at p.183), this limestone boulder was found on the Acropole, near the temple of Inshushinak in 1903 (see the plan at the top of the page). It now survives as two fragments:

-

✴the larger one (Sb. 6):

-

•is decorated with reliefs of:

-

-a serpent, which surrounds a vertical cylindrical hole (hence the adjective ‘pierced’);

-

-a large lion, which curves around the left edge; and

-

-a foundation scene, in which a male deity is shown driving a foundation peg into the ground, with a Lama (goddess) behind him; and

-

carries an LE inscription (text B) across the top and behind the Lama, part of which was apparently obliterated by the carving of the foundation scene; and

-

✴the smaller one (Sb. 177):

-

•contains a relief of the rear of the crouching lion;

-

•carries the lower part of an Akkadian inscription, which reads:

-

“... whoever would erase [this inscription] and would destroy the [... ?]: May Inshushinak and Nergal tear out his foundation and lose [destroy ?] his descendants! My Lord […], provokes [disorder?] in his mind/understanding!”

Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, Table 1, at p. 172) assumed that, since this ‘curse formula’ is very similar to that in Sb. 17 (above), the upper part of this inscription would have recorded Puzur-Inshushinak as ensi of Susa, shakkanakku of the land of Elam.

Beatrice André and Mirjo Salvini (referenced below, at p. 58) suggested, somewhat tentatively, that part of the broken line 3 of the Akkadian inscription on object §8 could be restored as [...] EREN.GAL, with EREN meaning ‘cedar. Beatrice André-Salvini (referenced below, entry 54, at p. 89) subsequently observed that the presence of the word ‘cedar here’:

-

“... might provide us with a clue to the meaning of the text [and thus to] the purpose of the boulder [Sb. Akkadian inscriptions on two other monuments, [Sb. 17 and Sb. 160 above], state that Puzur-Inshushinak dedicated[an object of copper and cedar. It is conceivable, then, that a cedar stake capped in copper was driven through the hole in the centre of the boulder, thereby fixing the temple [= the nearby temple of Inshushinak ??] to the ground.”

I discuss the significance of the object of copper and cedar in more detail below.

Detail of the relief on Sb. 6 (above), which depicts a god driving a tapered peg into the ground

It is sometimes suggested that the object that the god drives into the ground in the relief of Sb. 6 might represent ‘copper and cedar’ nail that was possibly named in the Akkadian inscription on the boulder. However, after a comprehensive analysis, Richard Evans (referenced below, at pp. 80-1) concluded that the answer was ‘probably not’. Gian Pietro Basello, who was of the same opinion, suggested that this scene on the front of the boulder, in which:

-

“... a half-kneeling god ... [drives] a great (wooden?) peg into the floor or ground ... seems to represent a kind of ritual action involving a peg like [those] found in foundation deposits. In my view, it is a symbolic representation that acknowledged the taking of possession of something by a god through the king’s good offices.”

I would like to make a similar suggestion, based on the text that, a few decades later, was stamped on a brick (A 6095: RIME 3/2: 1: 2: 31; IRS 2) from Susa, which reads:

-

“Shulgi, the strong man, king of Ur, king of Sumer and Akkad, has [re]built for Inshushinak his temple and restored it to its (original) place”.

My suggestion is that, in the relief on the front of this boulder, Inshushinak is depicted in the act of ritually marking the exact location on the Acropole where his temple should stand for eternity.

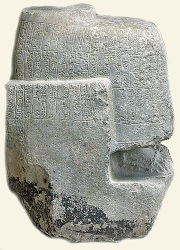

Fragment of a Votive Boulder (Sb. 172; Álvarez-Mon, §9; LE text D)

Pierced boulder from the Acropole of Susa, now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 172): image from museum website

Described as object 9 by Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below, 2018, at pp. 185)

According to Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018), this limestone fragment was found on the Acropole, near the temple of Inshushinak in 1903 (see the plan at the top of the page). In his entry §9 (at p. 185), he described it as a:

-

“...fragmentary [votive] boulder with a coiled serpent on top ... and a Linear Elamite inscription [LE text D, discussed above]. The boulder is split in half, revealing the interior of the cylindrical shaft, which pierced right through the entire body. The serpent is decorated with hexagonal scales similar to the serpent in boulder §8 and must originally have coiled around a post placed in the centre.”

As discussed above, although the LE text D does not apparently name Puzur-Inshushinak (see François Desset, referenced below, 2012, at p. 113), Javier Álvarez-Mon (see his Table II, at p. 191) argued that it should be considered (along with the pierced boulder §8, discussed above and the pair of lions discussed below) as one of three ‘votive pole-holders’ of Puzur-Inshusinak.

Pierced Pair of Lions (Sb. 98 and 99: Álvarez-Mon, §6; Anepigraphic)

Roaring Guardian Lions from the Acropole of Susa, now in the Musée due Louvre (Sb. 98 and Sb. 99)

Images from the museum website

According to Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, entry §6, at p. 182-3), this pair of almost identical crouching lions was found on the Acropole, near the temple of Inshushinak in 1903-4 (at trenches 23 and 24: see the plan at the top of the page). He observed that:

-

“The lions are quite eroded, but the style of body treatment brings them close to the lions depicted in the statue of Narundi [sic]. ... Both have a vertically-bored circular hole (11cm in diameter) piercing through their mid-section.”

As noted above, he argued (see his Table II, at p. 191) that this pair of objects should be considered (along with the pierced boulders §8 and §9 discussed above) as one of three ‘votive pole-holders’ of Puzur-Inshusinak.

Objects of Copper and Cedar and Pierced Objects: Analysis

As we have seen, two of the inscriptions discussed above refer an ‘object of copper and cedar’. As Gian Pietro Basello (referenced below, at pp. 42-3) observed, in both cases, this object is described as a ‘GISH.KAK’ (the logogram for the Akkadian ‘sikkatu’):

-

✴in the inscription on Sb. 17 (the tablet with lion head), which recorded that Puzur-Inshushinak had presented this object to Inshushinak, it is described as ‘URUDU GISH.KAK EREN’ (a copper GISH.KAK of cedar); and

-

✴in the inscription of Sb. 160 (the stele mentioning the opening of the Sidari canal), which recorded that Puzur-Inshushinak commemorated this event by ‘supplying ?’ the gate of Inshushinak with this object, it is described as ‘URUDUe GISH.KAK.EREN’ (a GISH.KAK of copper (and) cedar).

It is widely accepted that:

-

✴URUDU = copper (see Daniel Foxvog, referenced below, ‘urudu, uruda’, at p. 75); and

-

✴EREN = cedar (ibid, ‘gišeren, gišerin’, at p, 19).

However, although Basello interprets ‘GISH.KAK’ as ‘nail’ in the translationss above, there are other possibilities: see, for example:

-

✴Daniel Foxvog (referenced below, ‘giš)gag (or kak)’, at p. 21) gives ‘peg’, ‘nai’l, ‘cone’ and ‘plug’;

-

✴Daniel Potts (referenced below, 2016, Table 4.12, entry 2, at pp. 113) gives ‘bar/bolt’; and

-

✴Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, at p. 184 and note 93) adds ‘stake’, ‘lock’ and ‘barrier’.

Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, at p. 191) suggested that it is:

-

“Within the range of possibilities ... that [the object of copper and cedar in these inscriptions] refers to, or was similar to, the one held by the standing lions portrayed at the back of ‘Narundi’s. throne [see above].”

However, as we have seen, the ‘range of possibilities’ seems to be very wide indeed.

To take this further, we should now consider what (if anything) the inscriptions tell us about the function of this/these mysterious copper and cedar object(s). For example, we know from the text on Sb. 17 that Puzur-Inshushinak presented or dedicated such an object to Puzur-Inshushinak. Furthermore, given the find spot of the tablet, we might reasonably assume that the object in question was subsequently kept in or near the Inshushinak temple on the Acropole. However, pace (for example):

-

✴Daniel Potts (referenced below, 2016, Table 4.12, entry 3, at pp. 113) and

-

✴Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, at p. 183);

we cannot assume that this was a ‘foundation object’ related to the temple (or to anything else): as Richard Ellis (referenced below, at p. 81) observed, the occasion commemorated in the text on the stele SB. 160 was not the construction of the gate of Inshushiak (which was where the copper and cedar object was placed):

-

“... but something quite different: the ‘opening’ of [the Sidari canal].”

If we turn now to the Sb. 160 text, opinions vary as to the physical relationship between the copper and cedar object and Inshushinak’s gate: for example:

-

✴according to Richard Ellis (referenced below, at p. 80), Puzur-Inshushinak placed the object in the gate;

-

✴according to Florence Malbran-Labat (referenced below, 2018, at p. 466), he placed it at the gate;

-

✴according to Daniel Potts (referenced below, 2016, Table 4.12, entry 2, at pp, 113), he decorated the gate with the object;

-

✴according to Gian Pietro Basello (referenced below, at p. 43), he supplied the gate with the object; and

-

✴according to Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below, 2018, at p. 193), he (similarly) provided the gate with the object.

Furthermore:

-

✴Gian Pietro Basello (referenced below, at p. 42) introduced the Sb. 160 inscription by asserting that:

-

“... Puzur-Inshushinak celebrated the opening of a canal setting up [this copper and cedar object] in a door, suggesting that this was a public act to be performed in specific public places like the gate of a city”; while

-

✴as we have seen, according to Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, at p. 193) the relevant passage should be translated as follows:

-

“... when he (Puzur-Inshushinak) opened the canal to/from Sidari, he:

-

• erected a statue before the gate (bâb) of the temple (of Inshushinak); and

-

• provided his (temple) gate with [an object of copper and cedar].”

The basic problem seems to be that:

-

✴the precise meaning of ‘GISH.KAK’ depends on context in which it each object was employed; and

-

✴the corresponding inscriptions throw little light on the matter, given their enigmatic nature and the uncertainty as to the archeological context in which their were found.

Indeed, we cannot even establish whether the copper and cedar objects of SB, 17 and Sb. 160 were;

-

✴very different objects, albeit made of the same materials;

-

✴quite similar objects in most respects; or

-

✴one and the same object.

All we can really say about them is that they were both extremely prestigious objects, fit for Puzur-Inshushinak to offer to his lord, Inshushinak.

We can now look again at the three objects that Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below 2018, at pp. 191-2) characterised as ‘pierced’ monuments that were intended to hold a pole of about 10 cm in diameter’:

-

✴a pair of almost identical lions (§6); and

-

✴two votive boulders, each of which had a relief of a coiled snake surrounding its piercing:

-

•one (§8) with additional reliefs of a lion and a ‘foundation scene’; and

-

•another (§9) that is more fragmentary;

He also suggested that the:

-

“... ‘ritual and symbolic value’ of these [pierced] objects is underlined by the Akkadian inscriptions on:

-

✴the votive tablet with lion head (§7), discussed above; and

-

✴the votive boulder with lion, [snake and foundation scene] (§8):

-

both of which:

-

“... state that Puzur-Inshushinak dedicated to Inshushinak a ‘copper and cedar post/nail/peg’.”

In fact, as Gian Pietro Basello (referenced below, note 201, at p. 44) pointed out:

-

“No mentions of Puzur-Inshushinak are preserved in the Akkadian inscription [on (§8), albeit that] ‘[...]⌈ EREN⌉ .GAL’, (with EREN = ‘cedar’) has been tentatively restored on line 3 [by Beatrice André and Mirjo Salvini (referenced below, at p. 58)] ”

Thus, there is no certain evidence to link the objects of copper and cedar discussed above to these three ‘pierced’ objects.

In short, we actually know relatively little about the way in which Puzur-Inshushinak expressed his devotion to the gods of Susa in general and to his lord, Inshushinak, in particular. However, we can certainly agree with Javier Álvarez-Mon (referenced below, 2018, at p. 192-3) that:

-

“While the explicit ‘spiritual entity’ ... of these objects remains undefined, their ceremonial and symbolic nature cannot be denied. The religious contexts in which they were found indicate that the artistic agenda of Puzur-Inshushinak at Susa was conceived as part of a broader program. Gathered together, the monuments previously discussed form part of a cultic scenario [that included] inscribed royal and divine sculptures, roaring protective lions and serpents, votive tables, ... pierced boulders .... [and] copper and cedar posts. They bespeak a rich and dynamic religious life associating commemorative events with the Susa Acropole that comes to life in [the inscription of the inscription on the stele of Puzur-Inshushinak [(Sb. 160)].”

Victory Monuments of Puzur-Inshushinak

Seated Statue of Puzur-Inshushinak (Sb. 55; Álvarez-Mon, §4)

Side view of the lower part of a statue of a man wearing sandals, from Susa, now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 55)

Image from the museum website

According to Javier Álvarez Mon (referenced below 2018, at pp. 179-80), the now-incomplete limestone statue illustrated above was found in 1909 on the eastern edge of the Acropole (see the plan at the top of the page) and is now in the Musée due Louvre (exhibit Sb. 55). Vincent Scheil (referenced below, 1914, MDP 14, at p. 7), who recognised it as a statue of Puzur-Inshushinak, whom he characterised as an important historical figure similar to the more famous King Gudea of Lagash, observed that:

“[Although] the upper part of the body to the pelvis is missing, which is a loss for archeology the lower part covered with inscriptions survives, which is most fortunate for epigraphy”, (my translation).

He also observed (at p. 9) that:

-

“A long inscription covers the back and sides of [Puzur-Inshushinak’s] robe, as well as part of the seat, and must also have continued on the front of the apron, judging by a few isolated and imprecise remains of characters. It summarises his great campaign, listing the large number of conquered countries and cities ... Few names are familiar to us. The theatre of these wars is to be found to the east and north of Susiana, not in the south .... A replica of the present inscription [was published in MDP 6, referenced below, on the basis of] a copy of the original, which disappeared during transport between Susa and the sea. We will extract a few city names that are missing from the new text from the lost copy ...”

He then published (at p. 7-16) a translation of the completed inscription and a translation into French. Daniel Potts, referenced below, 2016, entry 1 in Table 4.12, at p. 113 ) summarised it as follows:

-

“[Puzur-Inshushinak], governor of Susa, [general] of the land of Elam, son of Simpi-Ishuk, captured the enemies of Kimash and Hurtum, destroyed Hupsana and crushed under his feet in one day 81 towns and regions; when the king of Shimashki came to him, he (the king) grabbed his (Puzur-Inshushinak’s) feet; Inshushinak heard his prayers and ...”

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 294 and note 11) pointed out, the 81 cities included Huhnuri, the most easterly city named in this passage ( see MDP14, col. 3, line 1, at p. 13 for this place name and Daniel Patterson, referenced below, at pp. 239-41 for its probable location at Tappeh Bormi, between Susa and Anshan). I discuss this important information about Puzur-Inshushinak’s territorial expansion further below.

Melissa Eppihimer (referenced below, at p. 128) pointed out that scholars still debate whether Puzur-Inshushinak:

-

✴re-purposed an Akkadian ‘royal’ statue here (in her words, ‘physical appropriation’); or

-

✴simply followed the Akkadian tradition for statues of this kind (in her words, ‘visual appropriation’).

She did not offer her own opinion, but she observed (at p. 199) that, in either case, the Akkadian model of kingship was clearly central to Puzur-Inshushinak’s approach to ‘self-presentation’ at this stage in his career. Interestingly, he still used the traditional titles of an Akkadian governor at this time (at least in this inscription from Susa).

Victory Statue of Puzur-Inshushinak (Sb. 48; Álvarez-Mon, §3)

Anepigraphic ‘victory statue’ from the Temple of Inshushinak at Susa, attributed to Puzur-Inshushinak

Now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 48): image from the museum website

According Javier Álvarez Mon (referenced below 2018, at p. 176 and note 42), the now-incomplete anepigraphic limestone statue illustrated above unearthed on 1904 under the paving of the temple of Inshushinak (see the plan at the top of the page) and is now in the Musée due Louvre (exhibit Sb. 48). The bare feet of the subject can be seen within a niche cut into what is otherwise a floor-length robe. It is clear that this is a figure of a triumphant military leader, because, as Álvarez Mon pointed out, the circular the base of the sculpture:

-

“... preserves a victory relief depicting [at least] four naked human corpses with fragmentary captions, [and] there was [possibly] was a fifth ruler depicted in the missing section [at the rear] of the base.”

Each of the corpses was originally identified by a horizontal inscription of his body: the two legible Akadian texts read:

-

✴‘Akukuni ensi’; and

-

✴‘Urnuntag (or Urishum), ensi of Nirrab.

Unfortunately, neither man can be identified, and the location of Nirrab is similarly unknown.

Melissa Eppihimer (referenced below, at p. 129) pointed out that scholars originally assumed that this was:

-

“... an Akkadian royal statue depicting the king’s defeated enemies beneath his feet.”

However, she observed that, in some respects, this statue departs from Akkadian precedent, not least in that:

-

✴it is made from limestone (as, for example, is Sb. 55, discussed above); and

-

✴the ruler’s feet are housed:

-

“... within a niche, a feature absent from the [known] Manishtushu and Naram-Sin standing statues.”

She acknowledged that it could still be an Akkadian royal statue, perhaps made in a non-Akkadian workshop, but she argued that it could also be:

-

“... a post-Akkadian statue (possibly of Puzur-Inshusinak) that adhere to an Akkadian prototype.”

Javier Álvarez Mon (referenced below, 2018) was less circumspect: he identified:

-

✴the standing figure as Puzur Inshushinak (see the title at p. 176 and the references to ‘Puzur-Inshushinak’s robe’ at p. 178 and p. 179); and

-

✴the corpses below his feet as those of defeated Zagros highlanders (see p. 177).

He argued (at p. 177) that that one of the best visual analogies to the iconography of Sb. 48 are provided by the Sippar stele of Naram Sin (Sb. 4), which depicts his victory over the Lullubi in the Zagros mountains and strongly suggests that, in this triumphal image, Puzur-Inshushinak was (probably consciously) emulating Naram-Sin’s royal imagery.

Steps of Inshushinak

Akkadian Inscriptions

Reconstruction by Beatrice André and Mirjo Salvini (referenced below, Figure 9, at p. 68) of the relative positions

of some of the surviving fragments of the Akkadian inscriptions on the putative steps of Inshushinak at Susa

Sb numbers relate to the numbers of the steps in the Musée du Louvre

Beatrice André and Mirjo Salvini (referenced below, at pp. 62-3) discussed 13 (mostly fragmentary) limestone slabs from Susa in the Musée du Louvre, each of which carried an Akkadian inscription on one of its four longer faces. They noted (as summarised in the illustration above) that two of them (Sb 156 and Sb 149) carried overlapping parts of the same text, which they translated as a composite(at p. 65) as follows:

-

“To (his) Lord, [I am] Puzur-Inshushinak, mighty king of Awan, son of Shimpi-ishhuk. [In] the year in which Inshushinak looked upon [me] and gave [me] the four quarters to govern, [I] built [this] staircase. If anyone defaces this inscription, may Inshushinak, Shamash and Nergal destroy his roots his descendants . My Lord, provoke (trouble?) in his mind”, (at p. 65, my translation of their French: see also Javier Álvarez Mon, referenced below, 2018, at p. 175).

André and Salvini argued (at p.66 - see also Figure 8 at p. 67) that:

-

✴six other fragmentary steps in the museum carried part of the same text and had probably belonged to the same flight of steps:

-

•Sb. 137 and Sb. 153 in the sketch above; and

-

•Sb. 18451, Sb. 18453, Sb. 18454 and Sb. 18458.

André and Salvini then described (at p. 66) part of a much larger step (Sb. 151) in the museum that might have come from another staircase. The text was a variant of the text above:

-

✴it explicitly identified Inshushinak as the lord of Puzur-Inshushinak in line 1; and

-

✴more importantly, it lacked the reference to the ‘four quarters’: as they observed (at p. 70), Puzur-Inshushinak was styled here as:

-

“... ‘mighty king of Awan’, without any mention of the year name.”

The last lines of this text, which presumably contained a curse, were missing. They identified:

-

✴three other fragmentary steps in the museum (Sb. 150, 157 and 18455) that were smaller than Sb. 151 but began with the same text at line 1; and

-

✴another (Sb. 18452) that carried the text of a curse that differed from the one in Sb. 156 but might have replicated the now-missing curse of Sb. 151.

Thus, all five of these slabs could have carried the same text, and they had perhaps all belonged to a second staircase.

Finally, André and Salvini drew attention (at p. 68) to the unpublished Akkadian text on yet another limestone step in the museum ( Sb 157), which:

-

“... contains the most significant [text] variation ... While all [13 texts discussed above] give Puzur-Inshushinak the royal title da-num LUGAL za!/a-wa-anki [(mighty king of Awan)], a title that does not exist on any of his other monuments, [Sb. 157], although very damaged, allows us to read:

-

✴line 4: Puzur4 Insh[shshinak]; and

-

✴lines 5-6: en[si] shush[in(a)ki].

-

Line 7 is double, and we must expect the expression ‘shakkanakkku sha mati Elam(tim)ki’, [since this is the only likely title] that can be restored before the patronymic of line 8 ...”, (my translation).

Thus, we have 13 Akkadian ‘step’ inscriptions that implied three different titles for Puzur-Ishushinak (see André and Salvini, referenced below, note 35, at pp. 70-1):

-

✴ensi of Susa and shakkanakkku of the land of Elam (Sb. 157);

-

✴mighty king of Awan (Sb. 151, and probably SB. 150, 151, 18452 and 18455); and

-

✴mighty king of Awan and the four quarters (Sb. 156, and probably Sb 137, 149, 153, 18451, 18453, 18454 and 18458).

Linear Elamite Inscriptions

Sketches by Beatrice André and Mirjo Salvini (referenced below, Figures 5-7, at p. 62)

of three LE inscriptions from Susa

Sb numbers relate to the numbers of the steps in the Musée du Louvre

Beatrice André and Mirjo Salvini (referenced below, at pp. 62-4) discussed three limestone slabs from Susa in the Musée du Louvre (F (Sb. 155); G (Sb. 139); and H (Sb. 140A)), each of which carries a LE inscription on one of its four longer faces. At their time of writing (1989), it was not possible to decipher these inscriptions. However, as noted above, François Desset et. al. (referenced below, 2022, in the Appendix at pp. 55-7) returned to them in the light of the recent advances discussed above. They observed (at p. 55) that:

-

“Despite some variants, they basically represent the same text, which can be almost completely reconstructed on the basis of these three exemplars.”

They then offered the following composite translation (at p. 56):

-

“Puzur-Sushinak, king of Awan, (the one begotten by Shin-pishuk)

-

Insushinak loves him, (the city of) Huposhan, the … he (= Insushinak) burnt, enslaved ... (and)

-

presented to him. Whoever rebels … may it (this) be destroyed (or: realised)”.

They commented (at note 2b, p. 57) that ‘Huposhan’ here is probably the same city as Hupsana, a conquest of Puzur-Inshushinak that was also mentioned in the seated statue of him (Sb. 55) discussed above. Beatrice André and Mirjo Salvini (referenced below, at p. 69 and note 33) suggested that each of these slabs had probably belonged to one or other of the monumental staircases discussed in the previous section. (They supported this assumption by observing that each of the other known LE inscriptions appeared alongside an Akkadian one.) However, it seems to me that they more probably belonged to one or more other monuments, which would have commemorated Puzur-Inshushinak’s victory at Huposhan.

Puzur-Inshushinak’s Campaigns

Phases of Puzur-Inshushinak’s territorial expansion as proposed by Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013)

Map adapted from iotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, Figure 1, at p. 315)

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013) suggested that Puzur-Inshushinak’s territorial expansion can be conveniently split into three phases, as summarised in the map above. He first observed (at p. 294), that at some time after he Puzur-Inshushinak had established himself at Susa:

-

“.... he launched a massive campaign in the Zagros, from as far as

-

•Huhnuri in the east; and

-

•the Hamadan plain in the northwest;

-

the highpoint [of which] was the capture of the lands of Kimash and Hurti [Phase 1]”.

This however was apparently only the start: Steinkeller argued (at p. 295) that:

-

“... it was [Puzur-Inshushinak’s] conquest of Kimashand Hurti ... made it possible for [him] to move:

-

✴into the Diyala Region [Phase 2];

-

✴subsequently, into northern [Mesopotamia] [Phase 3].”

In the sections below, I discuss the evidence for each of these phases.

Phase 1: the Elamite Highlands

The evidence for this period comes from two of Puzur-Inshushinak’s own inscriptions (both of which were discussed above:

-

✴the LE inscription on three limestone steps (LE texts F-H, Sb. 130, 140A and 155) records that:

-

“Puzur-Sushinak, king of Awan, (the one begotten by Shin-pishuk): Insushinak loves him, (the city of) Huposhan [= Hupsana], the … he (= Insushinak) burnt, enslaved ... (and) presented to him”, (translated by François Desset et al. (referenced below, 2022, at p. 56); and

-

✴the Akkadian inscription of a seated statue of Puzur-Inshushinak records that:

-

Puzur-Inshushinak, [governor] of Susa, [general] of the land of Elam, son of Shimpi-ishuk:

-

•when Kimash and Hurti became hostile to him, he went and captured his enemies ...

-

•[He also]:

-

-destroyed (the otherwise unknown) Hupsana; and

-

-crushed under his feet in one day 81 [?] towns and regions, the most easterly of which was probably Huhnuri, between Susa and Anshan.

-

•When the king of Shimashki came to him, he [the unnamed king of Shimashki] grabbed his feet; Inshushinak heard his prayers and ...”, (see Daniel Potts, referenced below, 2016, entry 1 in Table 4.12, at p. 113, and also Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2013, at p. 294 and note 11, for his capture of Huhnuri).

Submission of the Shimashki

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 302) observed that this passage contains the earliest surviving record of the existence of a king of Shimashki (and, indeed, of the name of Shimashki itself). He argued that:

-

“The facts that Puzur-Inshushinak attached so much importance to his encounter with the unnamed ruler of Shimashki and recognised him as a ‘king’ must [indicate] that this individual was [an important] political figure in his own right, whose power, while inferior to that of Puzur-Inshushinak, was something to be reckoned with.”

I discuss the history of the ‘Shimashkian dynasty’ on the following page: for the moment, we should simply note that, while Puzur-Inshushinak’s career probably ended with his defeat at the hands of Ur-Namma, the Shimashki kings seem to have flourished in the Elamite highlands thereafter.

Phase 2: the Diyala Region

This region is named for the Diyala river, which rises in the Zagros mountains and flows into the Tigris at a point slightly to the south of modern Baghdad. We have no evidence for the circumstances in which Puzur-Inshushinak gained control of this region, but as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 295 ) pointed out:

-

“According to one of Ur-Namma’s inscriptions, which describes his conflict with Puzur-Inshushinak, the latter occupied the cities of ... [the Diyala region at the time of Ur-Namma’s accession].”

This is a reference to the so-called Isin inscription (mentioned above in the context of the synchronisation of the reigns of Puzur-Inshushink and Ur-Namma above). The full text records that:

-

“(I), Ur-Namma, mighty man, king of Ur, king of the lands of Sumer and Akkad: [I] dedicated (this object) for my life. At that time, the god Enlil gave (?) ... to the Elamites. In the territory of highland Elam, they (Ur-Namma and the Elamites) drew up (lines) against one another for battle. Their (??) king, Puzur-Inshushinak, ... (the cities of) Awal, Kismar, Mashkan-sharrum, the lands of Eshnuna, the lands of Tuttub, the lands of Zimudar, the lands of Akkad, all the people ...”, (RIME 3/2: 1: 1: 29, lines 11-23; see also the translation by Douglas Frayne, referenced below, at p. 35).

Although it is not absolutely clear from the (now-lacunose) inscription, it seems that Ur-Namma claimed to have ‘liberated’ the territories listed here from Puzur-Inshushinak before confronting him in the Elamite highlands). As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 296) observed:

-

“... independent proof of Puzur-Inshushnak’s possession of the Diyala region is provided by the fact that one of his inscriptions is dedicated to the goddess Belat-Teraban, ... [who] had her home in the Diyala Region, probably in the city of Eshnuna itself.”

This Akkadian inscription, which is on a fragment of a small statue of Puzur-Inshushinak that is now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 6642) named Puzur-Inshushinak as governor, [general] of the land of Elam, son of Shimpi-ishuk (see Javier Álvarez Mon (referenced below 2018, entries §10 and §11, at pp. 185-6).

The most interesting city on this list of Puzur-Inshushinak’s conquests is obviously Akkad, the erstwhile capital of Sargon and his successors. Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 123) observed that this city had been:

-

“... still under Akkadian dominion even under Shu-Durul, [the last king of Akkad named in the so-called ‘Sumerian King List’]; therefore, Puzur-Inshushinak must have gained control of Akkad thereafter.”

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p, 296) argued that:

-

“We can be quite confident that it was as a consequence of all these conquests ... [and], in particular, the capture of [Akkad] ... that Puzur-Inshushinak assumed the titles of the “powerful one” (da-n.m) and “the king of Awan” (LUGAL A-wa-anki).”

I will return to these observations below.

Phase 3: Northern Mesopotamia

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 295) argued that evidence for the putative third phase of Puzur-Inshushinak’s territorial expansion can be found in the prologue to Ur-Namma’s law code. The relevant passage has been translated as follows:

-

“At that time, by the might of Nanna, my lord, I liberated Akshak [sometimes given as Umma], Marad, Girkal, Kazallu and their settlements, as well as Usarum, which had been enslaved by Anshan”, (RIME 3/2: 1: 1: 20, CDLI, P432130, lines 117-34: see also Martha Roth, referenced below, at p. 16 and Piotr Michalowski, referenced below, at p. 185).

Steinkeller assumed that ‘Anshan’ here meant Puzur-Inshushinak, from which it followed that Puzur-Inshushinak’s conquests in the Diyala Region (Phase 2) had enabled him to go on to conquer much of northern Mesopotamia (Phase 3). However, Piotr Michalowski, referenced below, at p. 184), who had seen a pre-print of Steinkeller’s paper (see his note 25, at p. 183) argued that:

-

“... it is only speculation that Puzur-Inshushinak was still on the throne at the time that the armies of Ur repulsed the [Anshanites] from that part of Babylonia, since the only text that testifies to this action (the Ur-Namma [law code]) does not mention any foreign ruler by name.”

Anshan at the Time of Puzur-Inshushinak

To take this further, we need to look at the (scant) surviving evidence for the history of Anshan at this time. As discussed in the previous page, the Akkadian king Manishutush (ca. 2300 BC) conquered Anshan, after which he presumably incorporated it into the Akkadian province of Elam. The next mention of Anshan in our surviving sources comes in the inscription on a statue (known to scholars as Statue B) of Gudea, the independent ensi of Lagash during the Gutian period. The inscription on this statue, which is now in the Musée du Louvre (AO 2), records that Gudea:

-

“... conquered the ‘city of Anshan and (the land of) Elam’ (or perhaps the ‘cities of Anshan and Elam’) and brought its booty to Ningirsu, in (his temple) E-ninnu”, (RIME 3/1.01.07, St B composite, lines vi: 64-8; see also Piotr Steinkeller, 2013, at pp. 298-9 and note 40).

Since Gudea was not in the habit of publicising his military successes (indeed, this is the only known inscription in which he did so), we can be reasonably certain that his claim of conquests made in Anshan and Elam should be accepted.

Unfortunately, the dating of Gudea’s reign is still debated. For example, Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013) believed that he was still ruling Lagash when Ur-Namma invaded the Elamite highlands (see the Isin inscription above), and argued (at p. 298) that:

-

“The most likely assumption is that Gudea and Ur-Namma had formed a military alliance against Puzur-Inshushinak, ... [albeit that] we have no direct confirmation of this [hypothesis] so far.”

However, Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below):

-

✴observed (at p. 121) that:

-

“... a new critical evaluation of the archival evidence provided by Steinkeller ... revealed that the [relative dating of Gudea and Ur-Namma] was not as clear as had been assumed”; and

-

✴having analysed the relevant evidence, concluded (at p. 122) that:

-

“... Gudea has to be dated earlier [than Ur-Namma, although] perhaps his last year(s) overlapped with the beginning of Ur-Namma’s reign.”

In other words, it is likely that Gudea’s conquest of Anshan and Elam preceded Ur-Namma’s expulsion of:

-

✴Puzur-Insushinak from Akkad and the Diyala region; and

-

✴the Anshanites from the region around Akshak, Marad, and Kazallu.

On this basis, both Puzur-Inshushinak and the Anshanites presumably regained their independence from Gudea and subsequently expanded into Mesopotamia, where they remained remained there until they were driven out by Ur-Namma. However, there is no surviving evidence to suggest that Puzur-Inshushinak ever extended his territory eastwards beyond Huhnuri, which was probably some way west of Anshan (as discussed above) Thus, in my view, we should accept Ur-Namma’s testimony at face value: at some time before the publication of his law code, he had liberated ‘Akshak, Marad, Girkal, Kazallu and their settlements, as well as Usarum’ from the subjugation of a ruler of Anshan.

Puzur-Inshushinak’s Conquest of Akkad

As noted above, the implied title ‘mighty king of Awan and the four quarters‘ appeared in an Akkadian inscription on at least one monumental step (Sb. 156) from Susa and it probably also appeared on seven other (Sb 137, 149, 153, 18451, 18453, 18454 and 18458). It therefore seems likely that these steps belonged to one or more monuments that celebrated Puzur-Inshushinak’s conquest of the Diyala region and particularly his conquest of Akkad.

As we have seen, Puzur-Inshushinak’s father, Shimpi-ishuk, is not named in the AwKL. It is therefore possible that:

-

✴Gudea deposed Hit’a, the 11th king named in the list; and

-

✴at some time thereafter, Puzur-Inshushinak:

-

•established his power base in Awan/ Elam by expelling Gudea (or another non-Elamite ruler); and

-

•subsequently took Susa, adopting the ‘traditional’ Akkadian titles of ensi of Susa and shagina of the land of Elam.

It is also possible that he took Anshan (either at this time or on a later occasion), but there is no surviving evidence that he did so. On the basis of this earlier dating of Gudea’s reign we must place Puzur-Inshushinak’s control of the Elamite highlands in a period that:

-

✴began at some time after the invasion of Gudea; and

-

✴ended with the invasion of Ur-Namma.

As we have seen, Puzur-Inshushinak was ultimately unable to hold on to his conquests outside Elam: Ur-Namma, having united southern Mesopotamia, drove him out of the Diyala Region before engaging with him in battle ‘in the territory of highland Elam’. Unfortunately we have no direct evidence for the outcome of that engagement. However, an important paper by Gianni Marchesi (referenced below, 2013) throws some light on this problem: he re-published the inscriptions on two ‘forgotten’ fragments of vases from Ur (CBS 14934 and CBS 14935) that are now in the Penn Museum, which indicated that the vases themselves had been taken as booty after a king of Ur had attacked Susa. Importantly, he restored the name of this king in question as Ur-Namma, observing (at p. 285) that:

-

“In previous scholarship, the capture of Susa was generally counted among the deeds of [Ur-Namma’s his son], Shulgi, whom the majority of scholars considered to be the true builder of the Ur III empire. Beyond rendering unto Ur-Namma(k) that which is Ur-Namma(k)’s, the texts published here document a key episode in the history of the Ur III empire and of its eastwards expansion.”

These texts (as restored) certainly allow us to assume that Ur-Namma defeated Puzur-Inshishinak in the Elamite highlands and went on to expel him from Susa.

There is no reason to believe that Ur-Namma had any interest in extending his hegemony into the Elamite highlands, which probably explains why (as we shall see on the following page) the Shimaski kings were able to extend their territory into Elam, presumably at Puzur-Inshushinak’s expense (assuming, of course, that he had survived his encounter with Ur-Namma).

Puzur Inshushinak and the Awan King List

In the sections above, we have followed Puzur-Inshushinak’s career as he progressed (in the eyes of his Susian subjects) through the following series of titles:

-

✴ensi of Susa and shagina/ shakkanakkku of Elam (in the Akkadian inscriptions on a number of other inscribed objects including Sb. 55 and 157); and

-

✴after his important victory at Huposhan/ Hupsana and his subsequent receipt of the submission of the neighbouring king of Shimashki:

-

•king of Awan (in the LE inscriptions on the steps Sb. 139, 140A and 155);

-

•mighty king of Awan (in the Akkadian inscription on the step Sb. 151, which was probably duplicated on Sb. 150, 157, 18452 and 18455); and

-

✴probably after his victories in the Diyala region and, in particular, his conquest of Akkad:

-

•mighty king of Awan and of the four quarters (in the Akkadian inscription on the step Sb. 156, which was probably duplicated on Sb 137, 149, 153, 18451, 18453, 18454 and 18458).

This raises the question of why Puzur-Inshushiunak, who had adopted the Akkadian title shagina of Elam, subsequently rejected the Akkadian title ‘king (lugal) of Elam’ in favour of ‘king of Awan’. The immediately obvious answer would be that he claimed to have recovered the kingdom of Hit’a (who would later appear as the 11th of the kings in the AwKL). However:

-

✴Puzur-Inshushinak is the only Elamite ruler who is known to have used the title ‘king of Awan’; and

-

✴the AwKL (at least in the form in which it has come down to us) was obviously compiled during or after his reign.

We therefore cannot rule out the possibility that Puzur-Inshushinak himself commissioned the original list (and that the the other men named in it were blissfully unaware that they had been rulers of Awan, rather than of Elam). As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2018, at p. 181) observed, a century or more after the time of Puzur-Inshushinak, the newly compiled Sumerian King List (translated as a composite in CDLI: P479895) included:

-

“... a separate Awan dynasty, assigning to it three kings (whose names are not preserved).

The relevant passages record that:

-

✴when Balulu, the last of the Ur I kings, was ‘struck down with weapons’, the god-given rule of ‘Sumeria’ was ‘carried off’ to Awan’ (lines 146-7); and

-

✴it remained there throughout the reigns of three successive (but now un-named) kings of Awan: their reigns lasted (in total) for 356 years before Awan, in its turn, was ‘struck down with weapons’, and the kingship was ‘carried off’ to Kish (lines 157-61).

As Steinkeller (as above) suggested:

-

“While it is doubtful that, until the advent of Puzur-Inshushinak, Awan had succeeded in establishing any form of political hegemony over [‘Sumeria’], it is possible that it [had been] an important Iranian polity already in Early Dynastic times.”

This situation is represented in the first column of their Table 36 (reproduced above), in which Puzur-Inshushinak:

-

✴took over Akkad and norther Mesopotamia (see below) after the reign of king Shu-Dural of Akkad; and

-

✴held it until he was driven out by king Ur-Namma of Ur.

This table also reflects (in the next column) the contemporaneous expulsion of king Tirigan of the Gutians from Adab by king Utu-hegal of Uruk: one of Utu-hegal’s royal inscriptions (known from three later Babylonian copies) recorded that:

-

“The god Enlil, lord of the foreign lands, commissioned Utu-hegal, the mighty man, king of Uruk, king of the four quarters, the king whose utterance cannot be countermanded, to destroy [the Gutian] name”, (RIME 2: 13: 6: 4, CDLI P433096, lines 15-21).

As Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993, at p. 280) observed:

-

“Noteworthy is the king's adoption of the title 'king of the four quarters' [in this inscription, a title that was] last used by Narim-Sin and the Gutian ruler Erridu-pizir [mentioned above].”

Piotr Steinkeller(referenced below, 2013, at p. 296) reasonably argued that:

-

“We will be justified in assuming ... that it was as a result of his capture of Akkad that Puzur-Inshushinak [also] felt entitled to adopt these two designations, [‘mighty’ and ‘king of the four quarters’], for himself.”

Steinkeller P., ‘The Sargonic and Ur III Empires’, in:

Bang P. F. et al. (editors), “The Oxford World History of Empire (Volume 2): The History of Empires”, (2021) New York, at pp. 43-72

Steinkeller P., “History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays”, (2017) Boston and Berlin

Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-292

Suter C. E., “Gudea’s Kingship and Divinity”, in:

Yona s. et al. (editors); Marbeh Ḥokmah: Studies in the Bible and the Ancient Near East in Loving Memory of Victor Avigdor Hurowitz”, (2015) Winona Lake, IN, at pp. 499-524

Marchesi G., “The Sumerian King List and the Early History of Mesopotamia”, in:

Biga M. G. and Liverani M. (editors.), “Ana Turri Gimilli: Studi Dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer da Amici e Allievi “, (2010) Rome, at pp. 231-48

References:

Desset F. et al., “The Decipherment of Linear Elamite Writing”, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, 112:1 (2022) 1–60

Foxvog D. A., “Elementary Sumerian Glossary, after M. Civil (1967)”, on-line, revised 2022

Desset F. et al., “The Marhašean Two-Faced ‘God’: New Insights into the Iconographic and Religious Landscapes of the Halil Rud Valley Civilization and Third Millennium BCE South-Eastern Iran”, Journal of Sistan and Baluchistan Studies, 1 (2021): 60-61

Malbran-Labat F., “Akkadian in Elam”, in:

Vita J-P., “History of the Akkadian Language: Volume 2”, (2021) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 1316-3

Potts D. T., “Puzur-Inshushinak”, in:

Potts D. T. et al. (editors), “The Encyclopedia of Ancient History: Asia and Africa”, (2021) on-line

Álvarez-Mon J., “The Art of Elam (ca. 4200–525 BC)”, (202o) Oxford and New York

Eppihimer M., “Exemplars of Kingship: Art, Tradition and the Legacy of the Akkadians”, (2019) New York

Álvarez-Mon J., “Puzur-Inšušinak, the last king of Akkad? Text and Image Reconsidered”, Elamica 8 (2018) 169-217

Desset F. (2018a), “Linear Elamite Writing”, in:

Álvarez-Mon J. et al. (editors), “The Elamite World”, (2018) Oxford and New York, at pp. 397-415

Desset F. (2018b), “Nine Linear Elamite Texts Inscribed on Silver “Gunagi” Vessels (X, Y, Z, F’, H’, I’, J’, K’ and L’): New Data on Linear Elamite Writing and the History of the Sukkalmah Dynasty”, Iran, 56:2 (2018) 105–43

Malbran-Labat F., “Elamite Royal Inscriptions”, in:

Álvarez-Mon J. et al. (editors), “The Elamite World”, (2018) Oxford and New York, at pp. 464-80

Patterson D. W., “Elements Of The Neo-Sumerian Military”, (2018) thesis of the University of Pennsylvania

Steinkeller P., “The Birth of Elam in History”, in:

Álvarez-Mon J. et al. (editors), “The Elamite World”, (2018) Oxford and New York, at pp. 177-202

Potts D. T., “The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State; Second Edition”, (2016), New York and Cambridge

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I., “Part I: Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Volume 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 1-130

Marchesi G.., “Ur-Nammâ(k)'s Conquest of Susa”, in:

de Graef K. and Tavernier J. (editors), “Susa and Elam: Archaeological, Philological, Historical and Geographical Perspectives: Proceedings of the International Congress Held at Ghent University, December 14–17, 2009”, (2013) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 285-91

Michalowski P., “Networks of Authority and Power in Ur III Times”, in:

Garfinkle S. and Molina M. (editors), “From the 21st Century BC to the 21st Century AD: Proceedings of theInternational Conference on Sumerian Studies Held in Madrid, 22-24 July 2010”, (2013) Winona Lake, IN, at pp. 169-205

Steinkeller P., “Puzur-Inshushinak at Susa: A Pivotal Episode of Early Elamite History Reconsidered”, in:

de Graef K. and Tavernier J. (editors), “Susa and Elam: Archaeological, Philological, Historical and Geographical Perspectives: Proceedings of the International Congress Held at Ghent University, December 14–17, 2009”, (2013) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 293-318

Basello G. P., “Doorknobs, Nails or Pegs? The Function(s) of the Elamite and Achaemenid Inscribed Knobs”, in:

G.P. Basello and Rossi A. V. (editors), “Dariosh Studies II: Persepolis and its Settlements: Territorial System and Ideology in the Achaemenid State”, (2012) Naples, at pp. 1–65

Desset F., “Premières Écritures Iraniennes”, (2012) Naples

Frayne D. R., “The Zagros Campaigns of the Ur III Kings”, Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies, 3 (2008) 33-56

Steinkeller P., “Studies in Third Millennium Paleography: The Sign Kish”, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie”, 94 (2004) 175–85

Roth M., “Law Collections from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor”, (1995) Atlanta GA

Frayne D. R., “Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2334–2113 BC): The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Early Periods (Volume 2)”, (1993) Toronto, Buffalo and London

André-Salvini B., “Votive Boulder of Puzur-Inshushinak”, in:

Harper P.O. et al. (editors), “The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre”, (1992) Paris, entry 54, at pp. 88-9

Volk K., “Puzur-Mama und die Reise des Königs”, Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, 82 (1992) 22-99

André B. and Salvini M., “Réflexions sur Puzur-Inshushinak”, Iranica Antiqua, 24 (1989) 53–72

Sollberger E. and Kupper J. R., “Inscriptions Royales Sumériennes et Akkadiennes”, (1971) Paris

Ellis R. S.,“Foundation Deposits in Ancient Mesopotamia”, (1968) New Haven, CT

Hinz, W., “Zur Entzifferung der elamischen Strichschrift”, Iranica Antiqua, 2 ((1962) 1-21

van Buren E. D., “A Collection of Cylinder Seals in the Biblioteca Vaticana”, American Journal of Archaeology, 46:3 (1942) 360-5

Scheil, V., “Textes Élamites-Sémitiques (MDP 14)”, (1913) Paris

Scheil, V., “Textes Élamites-Sémitiques (MDP 6)”, (1905) Paris

Scheil, V., “Textes Élamites-Sémitiques (MDP 4)”, (1902) Paris

Foreign Wars (3rd century BC)

Home