Empires of Mesopotamia:

Akkadian Empire (ca. 2300 - 2200 BC)

Main Page: Akkadian Empire (2300-2200 BC)

Topics

Empires of Mesopotamia:

Akkadian Empire (ca. 2300 - 2200 BC)

Main Page: Akkadian Empire (2300-2200 BC)

Topics

Sargon of Akkad

Sargon’s Rise to Power

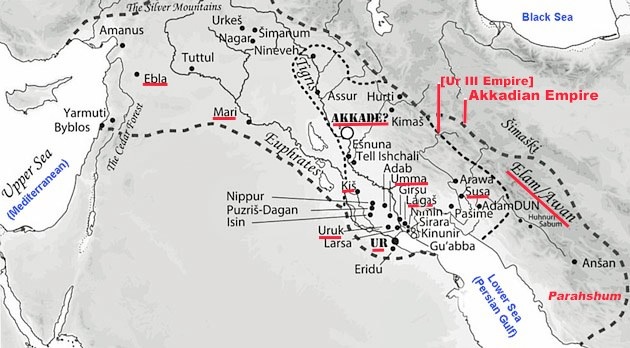

Image adapted from Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2021, Map 2.1, at p. 69)

My additions: text in red and blue

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2021, at p. 44) observed, the creation of the so-called Akkadian or Sargonic Empire by Sargon of Akkad (= Agade or Akkade):

“... was a completely novel experiment in the use of political power.”

Not least among the novel features of this ‘empire’ were the facts that:

✴the political power in question was passed down by dynastic succession, over a period of about a century, from Sargon to his great grandson, Shar-kali-sharri; and

✴at the height of their power, the dynastic kings of Akkad controlled the vast territory marked out in the map above.

Nevertheless (as the sharp-eyed will have noticed) Sargon’s capital is marked on the map as ‘Akkade ?’, since no archeological remains of this much-documented city have ever been found.

Victory stele of Sargon from Susa (now in the Musée du Louvre, Sb. 1)

Image from museum website: asterisk marks the figure of Sargon, identified by inscription

Furthermore, only two (fragmentary) royal inscriptions of Sargon survive in their original state:

✴an inscription (RIME 2:1:1:10, P461936, illustrated above) on the reverse of a victory stele from Susa names ‘Sargon, the king ....’; and

✴a fragmentary inscription (RIME 2:1:1:4, P217324) on a mace head from Ur (now in the Penn Museum: CBS 14396), which describes a now-unnamed king as the ‘conqueror of Uruk and U[r]’, can probably be assigned to Sargon on the basis of an Old Babylonian copy (RIME 2:1:1:5, P461930) from Nippur that records ‘Sargon, king of Akkad, conqueror of Uruk [and Ur].

Right: Fragment of a stele of a now-unnamed king (probably Sargon0 from Susa:

now in the Musée du Louvre (Sb. 2): image from museum website

Left: sketch of the relief from Lorenzo Nigro (referenced below, Figure 1, at p. 86), who identified the king on the left

as Sargon, clubbing the head of the captive Lugal-zagesi of Uruk and the goddess on the right as Inanna/Ishtar

Finally, the fragment above, which was found near stele (Sb. 1) at Susa, probably depicted Sargon after his victory over Lugal-zagesi of Uruk (see below). The fragmentary inscription (RIME 2.0.0.1002, P461912) contains part of a curse:

“... (may the gods ...) and Ilaba(tear out) his foundations.”

Apart from these ‘original’ inscriptions, the earliest surviving reference to Sargon is on the earliest known recension of the so-called Sumerian King List, which dates to the reign of the ‘Ur III’ king Shulgi (hereafter the USKL, transliterated at CDLI: P283804: ca. 2050 BC), which was published by Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003 - see my page on the USKL): in this inscription, after a long lacuna, we read that:

“Sargon, in Akkad, [ruled for] 40 years”, (reverse col. 1, lines 6’-7’ in the CDLI transliteration).

Unfortunately, we do not know how Sargon was introduced in the preceding (now-lost) USKL text. However, in the later Old Babylonian recensions of the Sumerian King List (hereafter the SKL), which were compiled after the fall of Ur during the period of the Isin kings, we read that:

“Sargon, whose father was a gardener, the cupbearer of (king) Ur-Zababa, the king of Akkad, the one who built Akkad, was king [there: he] ruled for 56 years”, (SKL 266-271).

I discuss the historical value of this relatively late biographical note below.

We are thus reliant for most of what we ‘know’’about Sargon’ career on copies of his royal inscriptions from the Old Babylonian period, augmented by various literary texts, the historical value of which is usually uncertain.

Sargon’s ‘Victory’ Inscriptions

Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1993, at p. 7) pointed out that, although very few of Sargon’s royal inscriptions survive in their original form:

“... a sizeable number [of them are] known from later Old Babylonian tablet copies: [in particular], two large Sammeltafeln [compilations of such copies] from Nippur:

✴one, [now] in Philadelphia (CBS 13972); [and]

✴the other, [now] in Istanbul (Ni 3200);

contain copies of several Sargon inscriptions. ... The originals of these copies may have been inscribed on triumphal steles that once stood in the courtyard of Enlil's Ekur temple in Nippur.”

He also observed (at p. 3) that:

“The Sargonic period marks the first time the Akkadian language was extensively used for royal inscriptions [in Sumer]. The majority of Sargon’s inscriptions are recorded in that language, [although] a minority are known in bilingual (Sumerian and Akkadian) versions, and a handful are in Sumerian alone.”

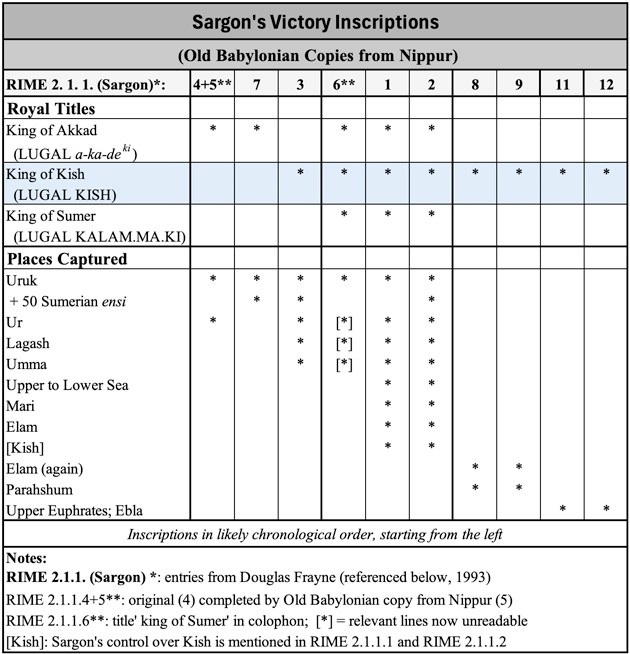

In the table above, I have summarised the contents of 10 of Sargon’s surviving ‘victory’ inscriptions (all of which except RIME 2.1.1.4, discussed above) are known from the Nippur Sammeltafeln: I have arranged them in the order suggested by the conquests to which they refer (in the hope that this roughly corresponds to their chronological order). It seems to me that the events described in these inscriptions probably fit into three chronological periods:

✴an early period, at around the time of Sargon’s conquest to Uruk and the rest of Sumer, when he used the title king of Akkad or king of Kish;

✴an intermediate period, in which he conquered Elam, Mari and other territory from the Upper to the Lower Sea, when he used three titles: king of Akkad; king of Kish; and king of Sumer; and

✴a later period, in which he consolidated his hold over Elam and extended his area of control to include Ebla to the north west and Parahshum to the south east, when he again used a single title, ‘LUGAL KISH’ (king of Kish).

I discuss this suggestion further in the following section, in the context of Sargon’s conquest of Kish. However, I will begin with an analysis of what is known about the evolution of hegemonic tendencies of Mesopotamian rulers before Sargon’s conquest of Kish.

References

Steinkeller P., ‘The Sargonic and Ur III Empires’, in:

Bang P. F. et al. (editors), “The Oxford World History of Empire (Volume 2): The History of Empires”, (2021) New York, at pp. 43-72

Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-92

Nigro L., “The Two Steles of Sargon: Iconology and Visual Propaganda at the Beginning of Royal Akkadian Relief", Iraq, (1998) 85-102

Frayne D. R., “Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2334–2113 BC): The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Early Periods (Volume 2)”, (1993) Toronto, Buffalo and London