Present Villa Fidelia Villa Fidelia in ca. 1830

Fresco in Palazzo Piermarini, Foligno

Villa Fidelia, which stands below the walls of Spello, now gives its name to a sanctuary here that was monumentalised in an impressive manner in ca. 27 BC. As discussed below, it seems that an earlier sanctuary here had belonged to Mevania, and that it was transferred to Hispellum at about the time of the deduction of the colony here in ca. 41 BC. Many scholars believe that this was the site of an ancient federal sanctuary of the Umbrians, a hypothesis discussed below.

Original Ownership

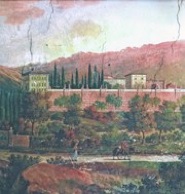

Locus sacer at Villa Fidelia

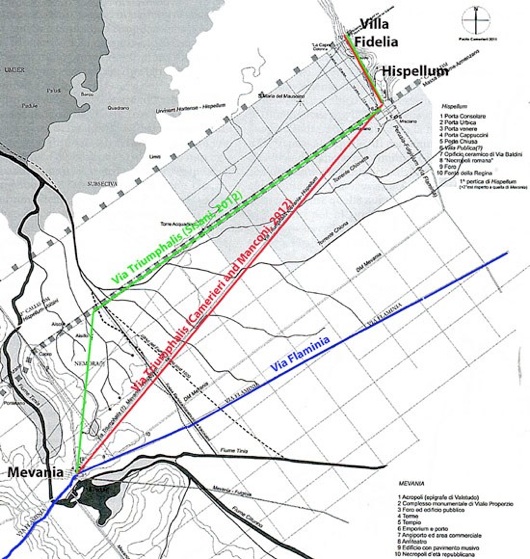

Adapted from Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, Figure 13)

See also, for example, Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, 2012, Figure 16)

A study of the centuriation of this part of the Valle Umbra by Manconi, Camerieri and Cruciani (referenced below, pp. 406-9) revealed that Villa Fidelia stands on the northeastern fringe of a rectangular ‘island’ of undivided land (illustrated above) that was:

-

✴not aligned with the centuriation of the land immediately surrounding it, which had been established for the new colony at Hispellum in 41 BC; but rather

-

✴aligned with the older centuriation of Mevania.

This rectangle extended to the southwest, extending some way beyond the area that was monumentalised in the Augustan period (see below). Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 430) pointed out that:

-

“... the new land division [at Hispellum] ... had evidently preserved and surrounded the undivided land that had previously been assigned to the ancient sanctuary. This enclave thus maintained its quality as a locus sacer [sacred place], along with its original orientation, which had been established in a previous programme of centuriation ... “ (my translation).

Sisani then drew the following conclusion:

-

“The coherence between [the orientation of the land belonging to] the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia and the centuriation of Mevania obviously indicates that:

-

-the sanctuary had originally belonged to Mevania; and

-

-it was transferred to Hispellum ... only at the moment when the colony was formed” (my translation).

As Sisani pointed out, the centuriation of Mevania occurred, at the latest, at the time of municipalisation (i.e. ca. 90 BC). There is no hard evidence for the ownership of the locus sacer before this time, but the fact that it was left undivided in 41 BC probably reflects a long history as a sacred place: Sisani reasonably assumed that it had probably enjoyed this status in the ownership of Mevania, rather than in the ownership of the less important centre at pre-colonial Hispellum.

Augustan Sanctuary (ca. 25 BC)

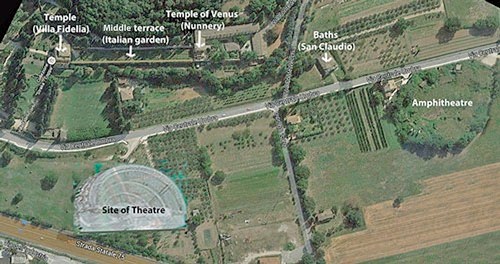

Aerial view of the site of the sanctuary as monumentalised in the Augustan period

The likely plan of the now-demolished theatre is overlaid at the lower left

As noted above, the sanctuary was monumentalised in ca. 27 BC. From that point, it comprised:

-

✴a system of three terraces, with the middle one now forming the Italian garden of Villa Fidelia;

-

✴two main temples, one at each end of this middle terrace:

-

•one temple almost certainly stood at the west end of the terrace, on the site of the present Villa Fidelia (although its existence is largely inferred from the symmetrical arrangement of the site); and

-

•the second temple (securely identified and known to have been dedicated to Venus after colonisation) stood at the east end, on a site that now belongs to the nunnery of the Suore Francescane Piccolo San Damiano;

-

✴a remarkably large theatre that was symmetrically located in relation to these two main temples;

-

✴a thermal complex near the site of the present church of San Claudio; and

-

✴an amphitheatre, slightly further to the east.

I discuss this monumentalisation in my page on Spello: Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia after Colonisation. However, I touch on tit here in order to provide a physical context for the discussion of the sanctuary in its earlier incarnations.

Cult Use before 41 BC

Archeological Evidence

The scant archeological evidence for the sanctuary in the period before it passed to Hispellum is known mainly from emergency excavations that were carried out in 1990 at the southwest edge of the site of the Augustan theatre. Fortunately, similar opportunities arose in relation to the Temple of Venus during work on the fabric of the nunnery in 1995-6 and again in 2011. However, with these exceptions, the site remains essentially un-excavated.

Cult Use in the Pre-Roman Period

Manconi, Camerieri and Cruciani (referenced below, p. 391, note 54) recorded the discovery in 1990 of:

-

“... a votive bronze in the form of a hand, typical for Umbrian sanctuaries of 5th and 4th centuries BC, found in the deeper strata [of the excavations]...” ( my translation).

This is the only evidence found so far for cult practices on the site that can be definitely dated to the period before the Roman conquest of Umbria.

Votive Altar of Jupiter (ca. 300 BC)

The excavations of 1990 also uncovered this small sandstone altar, which has an Umbrian inscription on one of its upper edges. This can be transcribed as:

iuvip(atre)

This probably refers to Jove the Father, or Jupiter. [Is it exhibited at the Museo Archeologico at Perugia ??] There is some uncertainty about the date of the inscription:

-

✴Alberto Calderini (in L. Agostiniani, referenced below, entry 27) dated the alphabet used in it to the period between the mid 3rd century and the early 2nd century BC, although he conceded that there was some uncertainty.

-

✴Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 424 and note 86) regarded this as too late, and alternatively dated it to the 4th or 3rd century BC.

Dorica Manconi (also in L. Agostiniani, referenced below, entry 27) asserted that the altar had almost certainly supported a small bronze votive offering to the god, which suggests the presence of a nearby temple of this dedication.

Temple (late 3rd/2nd century BC)

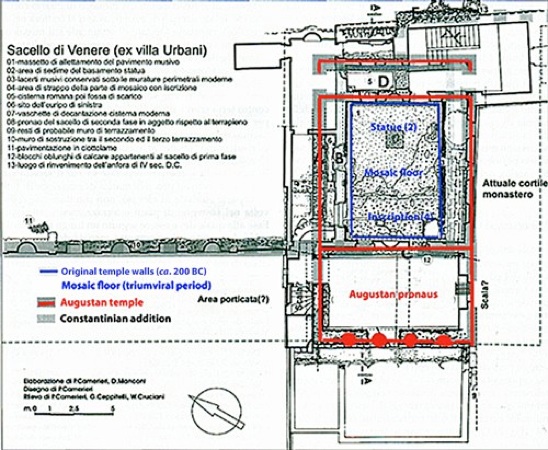

East temple of the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia in the imperial period

Adapted from Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, 2012, Figure 1)

With kind permission of the authors

Paolo Camerieri and Dorica Manconi (referenced below, 2012, at Figure 1 and pp. 67-8) discovered the remains of this temple in their excavations during the recent restoration of the nunnery of the Suore Francescane Piccolo San Damiano (which is shown in this photograph at the end of the Italian garden of Villa Fidelia):

-

✴In the 17th century, during the construction of what was then the Villa Urbani here, the mosaic floor of a temple (marked in blue in the plan above) was discovered and, within it, an inscription from the triumviral period that recorded the donation of a statue of Venus (as discussed below).

-

✴The recent excavations uncovered (inter alia) evidence for a smaller and earlier temple on the site, within the blue boundary above: its pavement had been destroyed when the ‘new’ floor (with its mosaic and inscription) had been installed at a lower level.

Camerieri and Manconi commented that:

-

“[The original construction of the temple] might be ascribed to roughly the period ... of the original urbanisation [of Hispellum] in the late 3rd or 2nd century BC, ... a period that saw the construction of the forum of the city [near Sant’ Andrea] ... in opera quadrata” (my translation).

Architectural Terracottas (2nd-1st century BC)

Manconi, Camerieri and Cruciani (referenced below, at p. 389) recorded that the excavations of 1990 also:

-

“... brought to light architectural terracottas of the 2nd-1st centuries BC, as well as other finds that support the hypothesis of the presence [here] of an ... Italic sanctuary” (my translation).

Unfortunately, these finds were never published, and the information above is all we have (as far as I know).

Interpretation of the Archeological Evidence

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 499) suggested, on the basis of the small votive altar found at Villa Fidelia, that the sanctuary here had probably been dedicated to ‘iuvipatre’ in the pre-Roman period, and that this deity represented:

-

“... a perfect parallel to Tinia, venerated at the [pan-Etruscan sanctuary of] fanum Voltumnae at Volsinii ... the probable model for the Umbrian sanctuary [at Hispellum]” (my translation).

Thus, in Sisani’s view, the tribes of pre-Roman Umbria belonged to an Umbrian Federation, with its federal sanctuary at Villa Fidelia dedicated to ‘iuvipatre’. The precedent for this had been provided by the city states of Etruria, whose federal sanctuary was, according to Livy, at the fanum Voltumnae. Thus, ‘iuvipatre’ was the “perfect parallel” to Tinia/ Voltumna/ Jupiter, the presiding deity at the fanum Voltumnae.

In a later paper (referenced below, 2007, at p. 286-8), Simone Sisani discussed what seems to have been an ‘ethnic revival’ at Mevania in ca. 100 BC, as evidenced by the apparent resurgence in the use of the Umbrian language here (and paralleled at Iguvium/ Gubbio). He suggested (at p. 286) that this revival should be understood in the context of the agrarian reforms proposed at Rome in the late 2nd century BC, which threatened the interests of municipal élites of Italy and perhaps fostered their assertion of their ethnic identity (a process that is often associated with the outbreak of the Social War in 90 BC). He observed (at p. 288) that these forces:

-

“... were certainly at work at Mevania, whose prominent role in reaffirming Umbrian identity was rooted in its very particular historical and institutional position as the ancient capital of the Umbrian League [and owner of] the ethnic sanctuary of Hispellum” (my translation)

He then (still at p. 288) interpreted the evidence of the architectural terracottas from this period found at Villa Fidelia in this socio/political context:

-

“At Hispellum ... we witness, in the last years of the 2nd century BC, the first monumentalisation in the Hellenistic style of the suburban sanctuary at Villa Fidelia, which can be identified as the religious heart of the [Umbrian] League. This constitutes the Umbrian parallel to the contemporary monumentalisation of the most important sanctuaries in Lazio and the Italic regions, an undertaking in which the expression of the economic power of local élites has long been recognised ...” (my translation).

Thus, in Sisani’s view, these architectural terracottas were evidence that the élite of Mevania, driven by their pride in their prominent position within the pre-Roman Umbrian Federation, had followed the example of the élites of Lazio and the Italic regions by monumentalising their ancient federal sanctuary (and, presumably, reviving ancient federal cult practices there).

I have to say that all this is a heavy weight to place on a single votive altar and an unedited collection of architectural terracottas that were found in a peripheral location in the sanctuary, in a context that, as a result of the emergency nature of the excavations, is not well defined. Specifically:

-

✴The small votive altar of ‘iuvipatre’, which is very difficult to date, cannot, in my view, be used as an indication that this was the dedication of a significant sanctuary here in the pre-Roman period.

-

✴In any case, even if one accepts that there might have been a significant sanctuary here dedicated to ‘iuvipatre’, this would not, on its own, lead to the conclusion that it must have had the same significance as the Etruscan federal sanctuary at the fanum Voltumnae, dedicated to to Tinia/ Voltumna/ Jupiter.

-

✴The terracottas from Villa Fidelia, which (as far as I know) are completely unedited and neither illustrated nor exhibited anywhere, nevertheless constitute evidence for the presence of one or more cult buildings here. However, the surviving snippets of information about them surely cannot support the hypothesis of a sanctuary here that was monumentalised on the scale, for example, of the sanctuary of the Pentrian Samnites at Pietrabbondante. (see below). This is not to deny any sort of religious revival here - see for example, my section on the Evidence of the ‘Cvestur Farariur’ at Mevania, below.

In summary, as John Scheid (referenced below, 2006, at p. 82) concluded, in a passage discussed in more detail below:

-

“It should first be noted that, according to the archaeologists, the large sanctuary at [Villa Fidelia] ... could have succeeded an important supra-regional sanctuary of the Umbrians. ... Unfortunately, all we know for certain at the moment is that this sanctuary had a supra-regional role in the [4th century AD, as evidenced by the Rescript of Constantine - see below]” (my translation and my italics).

Wider Arguments for a Federal Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia

Evidence from Livy

The following extracts from papers by Simone Sisani and Filippo Coarelli summarise the view that surviving classical sources support the existence of an Umbrian federal sanctuary near Mevania in the pre-Roman period:

-

✴Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, p. 493):

-

“It is absolutely probable that the concentration of the Umbrian army [at Mevania in 308 BC, reported by Livy (‘Roman History’, 9:41)] took place near the capital of the federation [i.e. Mevania], as is suggested by analogous examples, such as that of the Samnite dilectus of 293 BC at Aquilonia [ahead of a confrontation with the Romans in 293 BC, again described by Livy (‘Roman History’, 10: 38-41)]” (my translation).

-

✴Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, 2001, at p. 48):

-

“We know from Livy that, at least in 308 BC, the place where the Umbrian army mobilised [to plan an attack on Rome] was at Mevania. There must have been a nearby sanctuary of the Umbrian nomen, analogous to those we know about belonging to other pre-urban and proto-urban peoples of ancient Italy. One thinks here of the sanctuary of Pietrabbondante, for the Pentrian Samnites” (my translation).

-

✴Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 421):

-

“... the choice of [Mevania] for the mustering of the Umbrian army [in 308 BC] cannot have been accidental: as in the case of the tumultuous levy organised by the Samnites at Aquilonia in 293 BC, the choice must have fallen on the political and religious centre of the league, which could offer both the facilities (material and ritual) adequate for a concentration of such proportions and the necessary co-ordination of the actions of the separate contingents” (my translation).

I think that, in the second of these quotations, Filippo Coarelli was equating the sanctuary at Pietrabbondante with Livy’s Aquilonia (a suggestion that he had made in an earlier paper, referenced below, 1996). However Tesse Stek (referenced below, at p. 51) observed :

-

“... it is not entirely sure that Livy refers to a sanctuary proper [at Aquilonia ... However,] in a recent study [by Simone Sisani, referenced below, 2001], Pietrabbondante has .. been identified with Livy’s Aquilonia. If this is correct, which is difficult to prove, this means that the traditional sanctuary at Aquilonia/ Pietrabbondante was to some extent respected by the later construction phases.”

Thus, while it is not impossible, there is no hard evidence for a formal ethnic sanctuary at Livy’s Aquilonia that was later respected in the monumental sanctuary of the Pentrian Samnites at Pietrabbondante. The evidence for a formal Umbrian ethnic sanctuary near Mevania is even weaker: indeed, in the opinion of William Harris (referenced below, at p. 101):

-

“Although the Umbrian peoples naturally allied themselves for military purposes [in the pre-Roman period, as they had, for example in 308 BC], there is no evidence worthy of the name that there was an Umbrian League of any importance [that was placed politically] above the individual states.”

The muster of 308 BC at Mevania, like the muster of 293 BC at Livy’s Aquilonia, was probably attended by cult practices that cemented the alliance. However, in my view, Livy’s account of the muster at Mevania falls some way short of suggesting the existence of a permanent Umbrian Federation centred on Mevania, with a permanent federal sanctuary nearby.

Evidence of the ‘Cvestur Farariur’ at Mevania (ca. 100 BC)

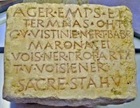

A late Umbrian inscription (ST Um 8), which uses an Etruscan alphabet, was found on this limestone sundial, which was ploughed up in 1969 outside Porta Cannara, Bevagna and which is now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Perugia. It reads:

[-.] p. nurtins.ia.t.ufeřie[r]

cvestur farariur

The names of two individuals:

-

✴p. nurtins, which can probably be Latinised as Publius Nortinus, who belonged to a family that is documented in other inscriptions from Mevania and also in inscriptions from tVolsinii (Bolsena) and whose family name probably derives from that of the Etruscan goddess, Nortia; and.

-

✴ia.t.ufeřie[r] can probably be Latinised as Ianto Aufidius, son of Titus, whose family name also appears in another Umbrian inscription (ST Um 25), which commemorates the uhter, pe. pe. uferier, as well as in later inscriptions fro Mevania

Nortinus and Aufidius held the post of ‘cvestur farariur’: the first word is probably equivalent to the Latin word ‘quaestors’, while the second suggests responsibilities that were related in some way to the supply of spelt. Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 422) suggested that their function was probably analogous to that of the “homons dur puri far eiscurent” (two men who come to fetch the flour) who appeared in Table Vb of the Iguvine Tables from Gubbio:

-

“The unique title [‘cvestur farariur’’ on the sundial from Mevania] finds a perfect parallel in the ‘homons pure dur to eiscurent’ [of Iguvium, who were] in charge of the collection of the tribute in flour offered by the participating districts during the so-called ‘ceremony of the tenths’, which constituted an expression of political and religious solidarity of the various people that belonged to the [so-called] Iguvine League” (my translation).

The implication is that the inscription on the sundial suggested that Mevania was at the heart of a similar communal ritual.

The find spot of the sundial was on the road from Mevania to Perusia. This road passed through Ospedalicchio (some 20 km north of Bevagna and 10 km west of Assisi), which was the find spot of a possibly related Umbrian inscription (which is also in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Perugia). This inscription (ST Um 10), which was broadly contemporary with that on the sundial (although it uses the Latin alphabet), referred to a acred field that had been bought and delimited for a religious purpose:

AGER EMPS ET TERMNAS .... SACRE STAHU

It took place during the period of office of:

-

✴the two men who held the post of uhter in the year in question:

-

•C(aius) Vestinius, son of V(ibius) and

-

•Ner(o) Babrius, son of T(itus); and

-

✴the two men who held the post of marone:

-

•Vois(ienus) Propartius, son of Ner(o); and

-

•T(itus) Voisienus, son of V(ibius).

Although the find spot ST Um 10 was on the periphery of Asisium, it was certainly linked to that city: the uhter Nero Babrius, son of Titus had the more junior post of marone in the (presumably earlier) Latin inscription (CIL XI 5390) that related to a major construction project there. Thus, it records an ‘official’ project that carried the imprimatur of the magisterial college of Asisium. Simoni Sisani (referenced below, 2012, pp. 422-3) proposed that the ‘cvestur farariur’ of ST UM 8 (above) were federal quaestors, and that:

-

“The chronological accord between [ST Um 10 and 25] makes it highly probable ... [that] the ager in the latter was the one specifically for the cultivation of sacred spelt that was offered by Asisium on the occasion of communal celebrations of the Umbrian League (my translation).

He explained (at p. 422) that the ritual would have been:

-

“... designed to seal the various components of the [Umbrian] federation on the basis of ethnicity, [as was the case in the] analogous ritual on Monte Albano celebrated by the people of the Latin League” (my translation).

These two inscriptions (ST Um 8 and 10) clearly represent the late use of the Umbrian language in the Valle Umbra at a time when Latin was taking the place of Umbrian, at least in public inscriptions. It is certainly possible (as Simone suggested) that:

-

✴given their find spots, they were related to each other; and

-

✴their content suggests that they related to a ceremony similar to the ‘ceremony of the tenths’ recorded in the broadly contemporary Table Vb of the Iguvine Tables, they related to a.

However, I see two main difficulties with the further hypothesis that these were the well-remembered rituals of an ancient ‘Umbrian league’:

-

✴With the exception of ST Um 10, the epigraphic evidence for Asisium at this time (including CIL XI 5390 above), points instead to a precocious ‘Romanisation’ of Asisium, as discussed in my page of the Ancient History of Asisium. Thus, for example, Filippo Coarelly (referenced below, 1991) entitled his paper of the subject:

-

"Assisi Repubblicana: Riflessioni su un Caso di Autoromanizzazione".

-

This does not invalidate the hypothesis of a the revival of an ancient communal ritual in the Valle Umbra, but it does make it difficult to understand the forces that might have caused the people of Asisium to take an active part in it.

-

✴The ‘league’ described in the Iguvine Tables seems to have involved only the districts that later coalesced at Iguvium. It certainly excluded at least one of the neighbouring communities: the ‘Tadinates’, who later coalesced at nearby Tadinum (Gualdo Tadino), were listed among the inveterate and hated enemies of the Iguvines. Thus, if the ritual described in these Tables is accepted as a precedent for a similar ritual in the Valle Umbra, the implication would be that the field at Ospedalicchio was remembered as having originally belonged to a district of Mevania, rather than to an autonomous member of an ‘Umbrian League’.

In short, if ST Um 8 and 10, taken together, are accepted as evidence for the revival of an ancient Umbrian ritual in the Valle Umbra, it is likely that this revival took place under the auspices of Mevania, and that Asisium played a willing but peripheral role in it. There is no evidence that any other Umbrian city participated in it, although that cannot be ruled out. This putative revival might have been associated with the possible monumentalisation at Villa Fidelia that is indicated by the discovery there of architectural terracottas from this period (discussed above). However, there is not hard evidence that the rituals revived were those of a pre-Roman Umbrian Federation.

Evidence from the Career of Aulus Rubrius

An inscription (

AE 1947, 0063), which was reused in the church of San Vincenzo, Bevagna and which is now in the Museo Archeologico there, reads:

A(ulus) Rubr[ius - f(ilius)]

harispẹ[x]/ Volsiniensi[s]

s(enatus) c(onsulto)

The local senate had decreed the posting of this inscription in honour of Aulus Rubrius, a haruspex (a priest who read the future by examining the entrails of sacrificed animals) who was associated in some way with Volsinii.

The inscription has been variously dated to:

-

✴the late Republican period, by Laura Bonomi Ponsi (in A. Feruglio et al., referenced below, pp. 86-7; entry 2:122), in the light of its epigraphy and the absence of a cognomen;

-

✴the early 1st century BC, by Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 503); and

-

✴the second half of the 1st century BC, in the EAGLE database (see the AE link above).

Laura Bonomi Ponsi (as above) pointed out that the name Rubrius is known from at least three other inscriptions from Mevania (CIL XI 7953, CIL XI 5068 and CIL XI 5041) but is not known in Volsinii. She therefore suggested that Aulus Rubrius probably came from Mevania and that he had been instructed in the art of haruspicy at Volsinii. Jean MacIntosh Turfa (referenced below) reported a similar opinion in her review of a book by Marie-Laurence Haack (referenced below), which I have not been able to consult directly:

-

“[Some] men seem to have recognised the cachet of Etruscan religious expertise, such as A. Rubrius (no. 79), an Umbrian who styled himself ‘Volsiniensis’ in the 1st century BC. [Haack] suggests that this expressed his having trained at Volsinii, presumably the [leading centre] of Roman religious academe [at that time], and that this is our earliest instance of an Etruscan office translating to an Italian/Roman position.”

Laura Bonomi Ponsi (as above) suggested more specifically that Aulus Rubrius had belonged to a ‘collegium haruspicum Volsiniensium’.

Francesco Roncalli (referenced below, at p. 230) also felt that the title ‘harispex Volsiniensis’ had an official air about it, and wondered whether Aulus Rubrius had been:

-

“... one of the sacerdotes [priests] recorded in the [much later] Rescript of Constantine [CIL XI 5265, ca. 335 AD] from Spello, which recorded that priests who were elected [annually or in alternate years] in order to represent the Umbrians, collectively, in annual celebrations held apud [at or near] Volsinii” (my translation).

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 503) agreed:

-

“... we could be dealing, not with a migrant from Volsinii nor with a local man who was educated there, but rather with one of the sacerdotes [priests] recorded in the Rescript of Constantine, who were elected by the Umbrians to participate in the ceremonies in the fanum Voltumnae. [Note that the Rescript does not actually mention the the fanum Voltumnae: it simple says that these meetings of the 4th century AD were held apud Volsinii]. The dating of the inscription [of Aulus Rubrius] is extremely significant: it testifies to the vitality of these ceremonies even at the start of the 1st century BC, at the time of the first monumentalisation of the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia [below] and the political career of Lucius Falius Tinia [below]” (my translation).

He expressed the same opinion a later paper (referenced below, 2012, at pp. 426-7):

-

“[The title ‘harispex volsiniensis’] demands to be understood as that of an Umbrian sacerdos [priest] expressly appointed to conduct his activities at Volsinii. [This] allows us to postulate the direct involvement of the community in the pan-Etruscan celebrations of the fanum Voltumnae” (my translation).

I discuss the relevant part of the Rescript of Constantine below. For the moment, I simply point of that nothing in the text of the Rescript suggests that the Umbrian priests who travelled to Volsinii each year were or ever had been haruspices. I think that the simpler explanation is more likely: that Aulus Rubrius, a native of Mevania, was esteemed in his native city because he had trained in haruspicy in what must have been the prestigious centre for such training at Volsinii.

Evidence from the Epitaph of Lucius Falius Tinia

Simone Sisani (2002, referenced below) published a detailed paper on a now-lost inscription (CIL XI 5281) on a funerary stele that was found in 1773, near the present railway station of Cannara (roughly midway, as the crow flies, between Spello and Bevagna). It read:

L(ucius) Falius L(uci) f(ilius) Tinia

cens(or), pr(aetor) bis, IIIIvir

Both the dating of the inscription and the municipium in which Falius served as quattuorvir are uncertain:

-

Since Simone Sisani assumed in his paper of 2002 that Falius had been a quattuorvir of Hispellum and suggested (at pp. 504-5) that he had probably been a member of the first college of quattuorviri after municipalisation in ca. 90 BC.

-

However, the EAGLE database (see the CIL link above) gives the find spot of the stele as “Hispellum?/Mevania?”, and assigns the inscription to the period 90-30 BC.

The post of praetor, which Lucius Falius Tinia held on two occasions, is problematic. Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 489) pointed out that it was unlikely to have been a civic post in a municipium at this time, and therefore reasonably suggested that it was more probably a priesthood.

More specifically, Sisani suggested (at p. 503) that:

-

“... the post of praetor held by Lucius Falius Tinia possibly maintains the memory of the supreme ... magistracy [of the Umbrian Federation]. This use of the title ‘praetor’ as a Latin interpretation of the Umbrian federal magistracy - of which the original [Umbrian] name does not survive - finds ... confirmation in the analogous case of the praetores of the Etruscan federation” (my translation).

In order to elaborate this last point, Sisani referred (at p. 504) to the inscriptions (1st century AD) known as the ‘elogia Tarquiniensia’, which record the careers of members of the Etruscan Spurinna family, two of whom (Velthur, son of Lars and Aulus, son of Velthur) had each held a post that was rendered into Latin in the inscription as ‘pr(aetor)’ on more than one occasion in the 5th-4th centuries BC. Sisani argued (following Mario Torelli, referenced below) that:

-

✴the descriptions of the careers of these men in the ‘elogia Tarquiniensia’ showed that they had each served as the supreme magistrate of the Etruscan Federation; and thus

-

✴the word ‘praetor’ in these inscriptions was the Latin rendition of the original Etruscan title of this magistracy (often given in Etruscan as ‘zilath mechl rasnal’).

Sisani therefore suggested (at p. 504) that:

-

“... the Umbrian praetor probably had as his unique role that of presiding over the communal rites of the [Umbrian] nomen at the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia” (my translation).

In a later paper, (referenced below, 2012, at p. 425), he asserted that:

-

“ ... I still believe that we should recognise [the post of praetor held by Lucius Falius Tinia] as a priesthood directly connected to the Umbrian ethnic league. The iteration of this priesthood [which Lucius Falius Tinia held twice] does not constitute an obstacle to this hypothesis, [since we might assume that] he belonged to the ranks of the priests selected annually by the Umbrians to preside over federal games, as evidenced by the so-called Rescript of Constantine [discussed below]” (my translation).

However, Tim Cornell (referenced below, at pp. 170-1), in his review of Torelli’s work, insisted that the engagements of the praetores Velthur and Aulus Spurinna described in the ‘elogia Tarquiniensia’, were most unlikely to have been federal in nature, since:

-

“... there is no historically verified instance in the literary sources of positive operations by a federal army organised by the Etruscan league.”

In any case, he observed that:

-

“Velthur I and Aulus Spurinna are referred to [in the ‘elogia Tarquiniensia’] simply as 'pr(aetores)'. ... If they were federal magistrates, why are they not described as such in the texts [using a specific title such as praetor populorum Etruriae] ?”

If Cornell is correct, then the earliest evidence we have for the Latin ‘praetor’ used to describe the chief priest of the Etruscan Federation relates instead to Sextus Valerius Proculus from Vettona (Bettona), who is recorded as a pr(aetor) Etruriae of the revived Etruscan Federation in the early 1st century AD in two inscriptions (CIL XI 7979 and AE 1996, 653b). This late example is clearly of no help in providing a precedent for the title of supreme magistrate of the putative Umbrian League in the Republican period. Further, we might reasonably ask, following Cornell:

-

“If Lucius Falius Tinia was the supreme magistrate of an Umbrian Federation, why was he described in CIL XI 5281 simply as ‘praetor’, rather than as ‘praetor Umbriae’?”

It seems to me that all we can reasonably assume is that Falius was twice elected to what was probably the priestly post of praetor. However, there is no firm basis for establishing the nature of this putative priesthood, and there is nothing to suggest that it was in any sense “federal”. It could have been associated in some way with the sanctuary at the Villa Fidelia (below), but we have no evidence for this.

Evidence from the Triumviral Period

A number of scholars have suggested that Hispellum was chosen for colonisation in 41 BC because of its proximity to the ancient ethnic sanctuary of the Umbrians. Thus, for example, Enrico Zuddas and Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, at pp. 57-8):

-

“If Appian [(‘Civil Wars’, 4:3)] was correct in stating that the cities chosen for [the deduction of colonies in 43 BC] were among the most prosperous and civilised of Italy, then [Hispellum seems to have been an exception]. ... The choice [in this case] seems therefore to have been dictated by other considerations: certainly by its centrality in the [Valle Umbra] but, above all, by the presence in its immediate vicinity of the federal sanctuary of Umbria, on the site of the present Villa Fidelia” (my translation).

John Scheid (referenced below, 2005, at p. 182) was more cautious when he placed the colonisation of Hispellum in the context of Octavian’s policy of religious restoration:

-

“In order that Italy [as well as Rome] benefitted from Octavian’s restorations, he paid attention to old and important Italic sanctuaries. For instance:

-

-he transformed the grove of Feronia (Lucus Feroniae in southern Etruria) and a sanctuary of Fortune (Fanum Fortunae, Umbria) into Roman colonies;

-

-he confirmed the privileges and the autonomy of the sanctuary of Diana Tifatina (Campania); and, finally

-

-he founded a colony at Hispellum, possibly an old federal sanctuary, and [also] gave [the new colony] responsibility for the famous sanctuary of Clitumnus [which had belonged to Spoletium]” (my italics).

He expanded on his hypothesis in a later paper (referenced below, 2006, at p. 82):

-

“It should first be noted that, according to the archaeologists, the large sanctuary at [Villa Fidelia] ... could have succeeded an important supra-regional sanctuary of the Umbrians. [As in other cases], the reason for the foundation of a colony [at the relatively small urban centre here might thus have been] the presence of [this putative] renowned Italic supra-regional cult site. Unfortunately, all we know for certain at the moment is that this sanctuary had a supra-regional role in the [4th century AD, as evidenced by the Rescript of Constantine]. ... The place was clearly very important. But, what interests us more particularly was another decision of Octavian, which [was probably] taken in the same context: he gave the famous sanctuary at the source of the Clitumnus to the Hispellates. ... In other words, he confiscated this cult site from Spoletium, which had owned it since the deduction of the colony [there in 241 BC]; and perhaps he similarly confiscated a supra-regional sanctuary at Villa Fidelia [from Mevania] to make a [new] colony and an urban centre” (my translation and my italics).

In my page on Spello: Colonia Julia Hispellum, I argue that Mevania had probably been selected for colonisation in 43 BC, but that Titus Resius, a patron of Mevania and also as legatus pro praetore (responsible for confiscating land and distributing it to veterans), was persuaded (or managed to persuade his superiors) to settle instead for the confiscation of:

-

✴the vicus at Hispellum, which would provide a good site for the urban centre of the new colony and was also close to tracts of good agricultural land that could be confiscated from Mevania and Asisium;

-

✴the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia; and

-

✴for good measure, the sanctuary of Clitumnus at the Fonti del Clitunno.

This would be sufficient for a prosperous colony that could, in addition, be placed at the heart of the religious life of the Valle Umbra.

Evidence from the Augustan Period: (I) the Augustan Theatre

The aerial view above gives an impression of the scale and layout of the sanctuary that was built at Villa Fidelia in ca. 27 BC, as described in my page on Spello: Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia after Colonisation. Filippo Coarelli (referenced below. 2001, at p. 47) suggested that:

-

“The dimensions of the [Augustan] theatre [here, which would have been] excessive for a small city like Hispellum, can be perfectly explained if it was intended for use by the whole nomen Umbro. We are [of course] dealing with an Augustan complex ... [However], from the [archeological] indications found to date [discussed above], which are scant but secure, it seems evident that the sanctuary [in its Augustan form] represented the monumentalisation of a much older structure. ... This monumentalisation ... is therefore one of many examples in the antiquarian Italian tradition, typical of the ideology of Augustus. An intervention on this scale would not have been justifiable if we were dealing with a local cult: we must be dealing with the ethnic sanctuary of the Umbrians” (my translation).

He concluded (at p. 49) that:

-

“We can construct with high probability the existence of an Umbrian federal centre, located between Mevania and Hispellum, based on the model of the fanum Voltumnae at Volsinii [the federal sanctuary of the Etruscans in the pre-Roman period]. This sanctuary also knew ... an antiquarian restoration in the Augustan period, which is known to us from the epigraphic evidence for the praetores Etruriae quindecim popularum [priests of a revived federation of 15 Etruscan peoples] in the imperial period]” (my translation).

In other words, in Coarelli’s view, Augustus had rebuilt the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia in order to reflect and celebrate its putative rôle as the federal sanctuary of the Umbrians in the pre-Roman period. He intended that it should be used by “the whole nomen Umbro”, presumably now reconstituted as a revived Umbrian Federation. This was directly analogous to his revival of the Etruscan Federation and his [presumed] restoration of the Etruscan federal sanctuary at the fanum Voltumnae.

As set out in my page on Spello: Colonia Julia Hispellum, I have considerable difficulties with this view of Augustus’ motivation for creating this magnificent sanctuary. It is true that he revived the pre-Roman Etruscan League in some form, but:

-

✴there is no evidence (pace Coarelli) that he rebuilt the fabled sanctuary at fanum Voltumnae; and

-

✴the earliest surviving epigraphic evidence for a praetor Etruriae (who is commemorated in CIL XI 7979 and AE 1996, 653b) dates to the early 1st century AD.

More generally, I doubt that thoughts of antiquarian restoration were foremost in Augustus’ mind in the period immediately after Actium, when the sanctuary was monumentalised. Even if (as Coarelli asserted) it had served “the whole nomen Umbro” in the pre-Roman period, the Augustan monumentalisation of it was, in my view, more probably conditioned by the political climate of the times.

Evidence from the Augustan Period: (II) the Via Triumphalis

Possible route of the via triumphalis mentioned in CIL XI 5041

Adapted from Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, 2012, Figure 17)

(The route in green is as proposed by Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, Figure 13)

As discussed in my page on

Valetudo and the Magistri / Novemviri Valetudinis, an inscription (

CIL XI 5041) in the Museo Archeologico of Bevagna records the paving of a road called the

via triumphalis (triumphal way) using stone from Hispellum. Only the lower part of the inscription survives, but it is almost certain that the project was financed by the

magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis (a magistracy unique to Mevania but probably similar in many ways to the

seviri and

seviri Augustales of other

municipia). According to Carlo Pietrangeli (referenced below, at pp. 58-9), this inscription was discovered under the street leading to the facade of the church of San Francesco in Bevagna (marked at the lower left in the plan above). There is some uncertainty as to the date of the inscription:

-

✴Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 416) dated it on paleographic grounds to the “primissima età imperiale” (i.e. to ca. 27 BC). If this is correct, then the paving of the via triumphalis would have have broadly coincided with the monumentalisation of the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia.

-

✴The EAGLE database (see the CIL link above) gives a later date for the paving (or re-paving) of the road, in the first three decades of the 1st century AD.

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 496) asserted that:

-

“The ritual nature of [via triumphalis at Mevania] is clear from its name: this is a unique parallel to the [via triumphalis] in Rome, which was associated with the [Roman] victories over the Etruscan city of Veii and with the archaic triumph. In the light of what we know about the oldest ‘Latin’ triumph, which had as its destination the federal sanctuary of Monte Albano, the [putative ancient] via triumphalis of Mevania can be identified with the road that linked Mevania, perhaps the political capital of the [putative Umbrian] League [in the 4th century BC], to the [putative] federal sanctuary that was located at nearby Hispellum” (my translation).

Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, 2001, at p. 48), who cited this paper by Sisani, reached broadly the same conclusion:

-

“[The via triumphalis at Mevania is] the only example of this denomination that we know outside Rome. The route of the triumph at Rome started at the sanctuary of Sant’ Omobono (the site of the temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta) and ended at the temple of Jupiter on the Capitol. In the case [of Mevania], the point of departure was probably a temple of Valetudo - probably a Roman interpretation of an Umbrian deity of virtus (bravery and military strength) as well as sanatio (healing) - while the point of arrival was at the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia, dedicated to Jupiter and Venus. The model, for both Rome and Mevania, was probably the sanctuary of the fanum Voltumnae at Volsinii, the centre of the Etruscan League and dedicated to the cult of (Tinia) Veltumna, the principal god of the Etruscans” (my translation).

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at pp. 417-8) deduced that it followed the route shown in red in the plan above.

Consistent with the theory that this sanctuary had long had a triumphal function, analogous with that of:

-

✴the sanctuary on Monte Albano (Sisani); and

-

✴those on the Capitol in Rome and at the fanum Voltumnae at Volsinii (Coarelli);

these scholars suggested that it too was dedicated to Jupiter, supported by the votive altar inscribed ‘iuvip(atre)’ that was discussed above. Thus:

-

✴As noted above, Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 499) suggested that, in its earlier incarnation, the whole sanctuary had probably been dedicated to ‘iuvipatre’, who represented:

-

“... a perfect parallel to Tinia [Tinia Velθumna], venerated at the [pan-Etruscan sanctuary of] fanum Voltumnae at Volsinii ... the probable model for the Umbrian sanctuary [at Hispellum]” (my translation).

-

✴Again, as noted above, Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, 2001, at p. 48) asserted that the point of arrival of the via triumphalis from Mevania:

-

“ .... was at the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia, dedicated to Jupiter and Venus” (my translation).

-

✴In his later paper, Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 437) asserted that:

-

“... the main temple [of the Augustan complex], probably dedicated to Iuppiter, which [scholars have tried] in vain to trace on the upper terrace, ... in my opinion should be sought below, in the vast area behind the theatre, [which would place it ] at the centre of the whole complex and in an emphatic position... “ (my translation).

In other words, according to both Sisani and Coarelli, in the Augustan period, the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis paved an ancient road from Mevania to the putative federal sanctuary at Villa Fidelia. It was still known as the via triumphalis because it was remembered as the route used for triumphal processions by the putative pre-Roman Umbrian Federation.

I have problems with this hypothesis:

-

✴I argued above that the small votive altar of ‘iuvip(atre)’ is required to carry a heavy weight here: in my view, it might indicate the original dedication of the sanctuary, and this might have been reflected in some way in the dedication of its Augustan successor, but this is no more than a possibility.

-

✴As set out in my page on Valetudo and the Magistri / Novemviri Valetudinis, I doubt (pace Filippo Coarelli, above) that Valetudo was “a Roman interpretation of an Umbrian deity of virtus (bravery and military strength) as well as sanatio (healing): she was more probably a Roman divine quality, like Victoria and many others. The involvement of the magistri / novemviri Valetudinis in paving the via triumphalis does not, in my view, indicate a link between Valetudo herself and the processional route: magistracies of this kind commonly undertook public works of this kind from the Augustan period onwards, simply in order to raise the status of their members (who, as in this case, were mostly freedmen who were ineligible for the more usual forms of public office).

I agree that the via triumphalis was probably a processional route from Mevania to the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia. However, I doubt that it had anything to do with ancient Umbrian triumphal ritual, not least because (as far as I am aware) there is no hard evidence that such a ritual ever existed. It seems to me that a road of this name that connected the newly-restored Via Flaminia in Mevania to the new pan-municipal sanctuary at Villa Fidelia, both of which had probably been financed using the spoils of he war in Egypt that had ended the civil war, was more probably associated with these recent events. The veterans and other supporters of Augusts who now provided the leading men of the municipia of the Valle Umbra, many of whom were from places outside Umbria, would surely not have needed memories of ancient Umbrian ritual to inspire them to create a processional route that would be used in celebrations of the triumphs and victories of Augustus.

Evidence of the Rescript of Constantine

Simoni Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 423) referred to:

-

“...the Constantinian rescript [or decree] from Hispellum, which documents, in unequivocal terms, the survival, at the beginning of the 4th century AD, of pan-Umbrian games that were closely linked to the pan-Etruscan games [held at] the ancient fanum Voltumnae at Volsinii and celebrated, according to all the evidence, at the find spot of the inscription [that recorded the rescript], which was discovered ... in the area of the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia ...”, (my translation).

This inscription (CIL XI 5265), which is now exhibited in the Sala Zuccari of Palazzo Comunale Vecchio at Spello, was discovered in 1733 in what was then a cemetery on the site that had once been the site of the Augustan theatre. It recorded the content of a rescript that had been issued by the Emperor Constantine and his sons in ca. 335 AD. In the rescript (or, more precisely, in the version of it that is reproduced in CIL XI 5265), Constantine replied (broadly in the affirmative) to three requests from Hispellum, two of which apparently related to Hispellum itself and do not concern us here.

For our present purposes, we need to consider only the third request, which the authorities of Hispellum seems to have been made on behalf of ‘Umbria’:

-

✴The rescript first set out the background to this third request:

-

“... you have asserted that you were joined to Tuscia in such a way that:

-

-according to istituto consuetudinis priscae [previous/ old/ ancient custom];

-

-per singulas annorum vices [each year/ in alternate years];

-

priests who are created by you and by the aforementioned offer theatrical shows and a gladiatorial contest apud [in, near] Volsinii, a city of Tuscia.”

-

✴The rescript then summarised the request:

-

“... because of the steepness of the mountains and the difficulties of the wooded routes [between the two cities], you have urgently demanded that, through the grant of a remedy, your priest may not be require to travel to Volsinii in order to celebrate the games and, specifically ...:

-

-that the priest whom Umbria had provided anniversaria vice [annually/ in alternate years] should [in future] offer a spectacle of both theatrical shows and a gladiatorial contest [at Hispellum];

-

-even while the same custom remains for Tuscia: that the priest created [there] should attend the spectacles of the aforementioned games at Volsinii, as was customary.”

-

✴Constantine’s reply was carefully worded:

-

“Consequenter (as a consequence) [of the erection of the Templum Flaviae Gentis at Hispellum], we ... grant you permission to host the games [at Hispellum], on the specific condition that ... the tradition of giving games shall not depart from Volsinii per vices temporis [annually; in alternate years], where the aforementioned festival shall be celebrated by priests created from Tuscia. In this way:

-

-not much will seem to be diminished from veteribus institutis [previous/ ancient custom]; while

-

-you, who come to us as suppliants ... will enjoy the pleasure of having obtained that which you so urgently demanded.”

I have relied on the English translation by Noel Lenski (referenced below, at pp 118-9) here. However, where the translation is disputed, I have given the Latin in Italics and then the alternative translations.

The first thing to notice is that the rescript never referred to ‘the Umbrians’ or ‘the Tuscians’. Rather, it says that:

-

-“... you have asserted that you were joined to Tuscia ...”;

-

-“... priests who are created by you and by the aforementioned [i.e. Tuscia]...”

-

-“... you have urgently demanded that ... your priest may not be required to travel to Volsinii”

-

-“... specifically, the priest whom Umbria had provided ... should [in future officiate at Hispellum], even while the same custom remains for Tuscia: that the priest created [there] should [continue to officiate] at Volsinii, as was customary.”

In short, on a strict reading:

-

-“you” means “Umbria” in this part of the rescript; and

-

-“you were joined to Tuscia” means “you, the people of Umbria, were joined to Tuscia”.

The most natural interpretation to put on the phrase “you, the people of Umbria, were joined to Tuscia” is that it refers to the creation of the province of Tuscia et Umbria at the time of the administrative reform that Diocletian carried out in ca. 295 AD. However, Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, 2001 at p. 44) argued against this “administrative” interpretation: he suggested that the request in the rescript, to the effect that the games should subsequently be held separately, at Volsinii and also at Hispellum:

-

“... aimed in reality at the restoration of [what must have been] the original situation, in which the two ceremonies had been separate ... The unification [alluded to in the rescript, whenever it had occurred] could have reflected an original rapport between the two centres and the two [autonomous] ceremonies, a rapport rooted in links that were probably idealogical and cultural (and, more precisely, religious) in nature, rather than political or administrative”(my translation).

Simoni Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 427) asserted that:

-

“... the phrase prisca consuetudo [in the rescript] is often understood as a relic of atavistic ties between the two ethnicities” (my translation);

and suggested that, before the formal ‘joining together’:

-

“... the priests elected by the Umbrian League were invited to attend pan-Etruscan games celebrated at Volsinii, without prejudice to the autonomous conduct of pan-Umbrian games at the ethnic sanctuary at Hispellum. It is impossible to place a secure chronology on this period of close rapport between the two peoples: [however], the little that we know about [the ancient] history of the region ... suggests a stable political-military alliance between the Umbrians and Etruscans from at least the beginning of the 4th century BC until the Battle of Sentinum [in 295 BC], directed against the common enemy [Rome]. We can imagine that this was sealed in the religious sphere through the sharing of their respective federal rituals” (my translation).

In order to locate the original Umbrian ceremonies, Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, 2001 at pp. 46-7) pointed out that:

-

“It would be difficult not to connect the games mentioned in the rescript with the structure of the sanctuary [at Villa Fidelia, where it was found: this sanctuary] included a theatre and amphitheatre [from the Augustan period], precisely the facilities used for ludi scaenici and gladiatorum munus [recorded in the rescript] ... It seems to me that the conclusion is inevitable: the games that were held at Volsinii by the Etruscans and the Umbrians in the 4th century AD were originally held separately: the decision to hold at Hispellum those involving the Umbrians did not, therefore, constitute a novelty, but merely a return to a prior practice, which we can probably identify as the ‘istituto consuetudinis priscae’ of the rescript” (my translation).

At this point, Coarelli had established a link from the Constantinian period back to ca. 27 BC, at the start of the principate of Augustus. In my view, his suggestion that the situation after the rescript might well have restored these annual games to the form in which they had existed in the Augustan period is a reasonable one. However, for the purposes of this page, it is necessary to consider whether the evidence of the rescript can take us still further back in time.

Filippo Coarelli (as above) continued:

-

“But, there is more: on the basis of scant but secure [archeological evidence], it seems that the [Augustan] sanctuary was nothing other than the monumentalisation of a much more ancient structure ... ; [it thus] provides another example of the antiquarian restoration of [pre-Roman] tradition that was typical of Augustan ideology. An intervention on this scale would not have been justified if we were dealing with a local cult: we must be dealing here with the ethnic sanctuary of the Umbrians, [later] reflected in the rescript ...” (my translation).

He summarised (at pp. 49-50):

-

“Far from constituting a late manifestation of the imperial administrative restructuring of Italy, [the religious association of Hispellum and Volsinii evidence by the rescript] is at the end of a long historical process, the roots of which are sunk deep in the soil of pre-Roman Umbria” (my translation).

In my view, this pushes the evidence too far:

-

✴In my section above on the surviving archeological evidence for the period before the Augustan monumentalisation, I argue that, whatever was meant by Coarelli’s description of it as “scant but secure”, it certainly does not, on its own, indicate the presence of a major ethnic sanctuary here.

-

✴In my section Evidence from the Augustan Period: (I) the Augustan Theatre (above), I argue that thoughts of antiquarian restoration were unlikely to have been foremost in Augustus’ mind in the period immediately after his famous victory at Actium. In my view, the decision to build the sanctuary, together with the impressive walls of the colony itself, was more probably conditioned by the exuberant triumphal mood of the times.

In short, the fact that we learn from the rescript that the people of Umbria, however defined, jointly celebrated annual games at Hispellum (probably at Villa Fidelia) after ca. 335 AD:

-

✴might reflect the restoration or partial restoration of a tradition that was introduced at the time of the monumentalisation of the sanctuary here in ca. 27 BC; but

-

✴cannot (pace Coarelli) be taken as evidence of “a long historical process, the roots of which are sunk deep in the soil of pre-Roman Umbria.”

Was Villa Fidelia the Site of a Pre-Roman Federal Sanctuary?

In trying to summarise my own opinion on this question, I find that I cannot improve on that of John Scheid (referenced below, 2006, at p. 82):

-

“... according to the archaeologists, the large sanctuary at [Villa Fidelia] ... could have succeeded an important supra-regional sanctuary of the Umbrians. [As in other cases], the reason for the foundation of a colony [at the relatively small urban centre here might thus have been] the presence of [this putative] renowned Italic supra-regional cult site. Unfortunately, all we know for certain at the moment is that this sanctuary had a supra-regional role in the [4th century AD, as evidenced by the Rescript of Constantine]. ... The place was clearly very important. But, what interests us more particularly was another decision of Octavian, which [was probably] taken in the same context: he gave the famous sanctuary at the source of the Clitumnus to the Hispellates. ... In other words, he confiscated this cult site from Spoletium, which had owned it since the deduction of the colony [there in 241 BC]; and perhaps he similarly confiscated a supra-regional sanctuary at Villa Fidelia [from Mevania] to make a [new] colony and an urban centre” (my translation and my italics).

But this leaves the question of whether Scheid’s “supra-regional sanctuary of the Umbrians” was, more precisely, the sanctuary of a pre-Roman federation of the tribes of Umbria:

-

✴As discussed above, the evidence of the inscriptions ST Um 8 and 10 and of the architectural terracottas discovered at Villa Fidelia could point to the revival of pan-municipal cult activity under the auspices of Mevania in ca. 100 BC.

-

✴However, whether this had anything to do with the cult practices of a pre-Roman federation of the tribes of Umbria is open to debate.

I tend to the view expressed by William Harris (referenced below, at p. 101), which was mentioned above:

-

“Although the Umbrian peoples naturally allied themselves for military purposes [in the pre-Roman period], there is no evidence worthy of the name that there was an Umbrian League of any importance [that was placed politically] above the individual states.”

If this is accepted, it follows that there “no evidence worthy of the name” for a pre-Roman federal sanctuary, at Villa Fidelia or anywhere else.

Read more:

N. Lenski, “Constantine and the Cities: Imperial Authority and Civic Politics”, (2016) Philadelphia

D. Briquel, “Il Sacrificio dopo la Guerra di Perugia”, in

G. Bonamenti (Ed.), “Augusta Perusia: Studi Storici e Archeologici sull' Epoca del Bellum Perusinum”, (2012) Perugia, pp. 39-64

P. Camerieri and D. Manconi , “Il ‘Sacello’ di Venere a Spello: dalla Romanizzazione alla Reorganizzazione del Territorio: Spunti di Ricerca ", Rivista di Antichità, 21 (2012) 63-80 S. Sisani, “I Rapporti tra Mevania e Hispellum nel Quadro del Paesaggio Sacro della Valle Umbra”, in:

G. Della Fina (Ed.), “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, (2012) Orvieto (pp. 409-64)

J. Warner, “Human Sacrifice at Perusia”, (2012), Sunoikisis Research Symposium

L. Agostiniani et al. (Eds), “Screhto Est: Lingua e Scrittura degli Antichi Umbri”, (2011) Città di Castello

D. A. Phillips, "The Temple of Divus Iulus and the Restoration of Legislative Assemblies under Augustus", Phoenix, 65: 3-4 (2011), 371-92

Zs. Várhelyi, “Political Murder and Sacrifice: from Republic to Empire,” in:

J.W. Knust and Zs. Várhelyi (Eds.), “Sacrifice in the Ancient Mediterranean: Images, Acts, Meanings”, (2011) Oxford, 125-41

P. Camerieri and D. Manconi , “Le Centuriazioni della Valle Umbra da Spoleto a Perugia”, Bollettino di Archeologia on line (2010)

P. Bonacci and S. Guiducci , “Hispellum: La Città e il Territorio”, (2009) Spello

G. Donadoni, “Ville e Residenze di Campagna nell' Umbria del Cinquecento”, (2009) thesis from the Università degli Studi ‘Roma Tre’

S. Guiducci, "Guida Turistica di Spello: Itinerari fra Storia, Arte, Natura”, (2009) Spello

T. Stek, “Cult Places and Cultural Change in Republican Italy”, (2009) Amsterdam

S. Sisani, “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

J. Scheid, “Rome et les Grands Lieux de Culte d’ Italie”, in:

A. Vigourt et al. (Eds), “Pouvoir et Religion dans le Monde Romain: en Hommage à Jean-Pierre Martin”, (2006) Paris, pp. 75-88

J. Scheid, “Augustus and Roman Religion: Continuity, Conservatism, and Innovation”, in:

K. Galinsky ((Ed.), “Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus”, (2005) New York, pp. 175-93

L. Baiolini, “ La Forma Urbana dell' Antica Spello”, in:

L. Quilici and S. Quilici Gigli (Eds), “Città dell' Umbria”, (2002) Rome, pp 61-120

S. Sisani, “Lucius Falius Tinia: Primo Quattuorviro del Municipio di Hispellum”, Athenaeum, 90.2 (2002) 483-505

S. Stopponi, “Da Orvieto a Perugia: Alcuni Itinerari Culturali”, Annali della Fondazione per il Museo Claudio Faina, 9 (2002) 229-65

F. Coarelli, "Il Rescritto di Spello e il Santuario ‘Etnico’ degli Umbri”, in:

“Umbria Cristiana: dalla Diffusione del Culto al Culto dei Santi,” Atti del XV Congresso Internazionale di Studi sull’ Alto Medioevo, (2001) Spoleto, pp. 39-52

S. Sisani, “Aquilonia: una Nuova Ipotesi di Identificazione”, Eutopia, New series 1-2 (2001) 131-47

F. Coarelli, “Legio Linteata: L’iniziazione Militare nel Sannio”, in

“La Tavola di Agnone nel Contesto Italico, Convegno di Studio, Agnone 13–15 Aprile 1994”, (1996) Florence, pp. 3-16

D. Manconi, P. Camerieri and V. Cruciani, “Hispellum: Pianificazione Urbana e Territoriale”, in:

G. Bonamente and F. Coarelli (Eds),“Assisi e gli Umbri nell' Antichità” Assisi (1996) pp. 375-423; the section on the sanctuary is at pp. 381-92

P. Fontaine, “Cités et Enceintes de l'Ombrie Antique” (1990) Brussels

L. Sensi, “Nuovi Testi Epigrafici di Età Romana da Spello”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 11 (1987) 7-38

J-P. Thuillier, “Les Édifices de Spectacle de Bolsena: Ludi et Munera”, Mélanges de l'Ecole Française de Rome: Antiquité , 99:2 (1987) 595-608

G. Gregori, “Amphitheatralia I”, Mélanges de l' École Française de Rome, 96 (1984) 961-85 M. Sensi and L. Sensi, “Fragmenta Hispellatis Historiae (1): Istoria della Terra di Spello, di Fausto Gentile Donnola”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 8 (1984) 7-136

T. Cornell, “Principes of Tarquinia: Elogia Tarquiniensia ... by Mario Torelli”, Journal of Roman Studies, 68 (1978) 167-73

W. Harris, “Rome in Etruria and Umbria”, (1971) Oxford

M. Brozzi, “Guida di Spello Romano”, (1972) Assisi

S. Weinstock, “Divus Julius”, (1971) Oxford

C. Pietrangeli, “Mevania”, (1953) Rome

R. Syme, “The Roman Revolution” (1939, latest edition 2002) Oxford

J. S. Reid, “Human Sacrifices at Rome and Other Notes on Roman Religion”, Journal of Roman Studies, 2 (1912) 34‑52

Ancient History: Pre-Roman Mevania Fonti del Clitunno

Mevania after the Conquest Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia before 41 BC Other Sanctuaries

Mevania after the Perusine War Valetudo and the Magistri Valetudinis

Return to the page on History of Bevagna.