It seems likely that, after the Roman conquest of 308-295 BC, Mevania (like many other Umbrian centres) retained its independence, but under the hegemony of Rome.

Republican Period

Urban Development

Mevania might well have been walled (or re-walled) shortly after the Roman conquest. Pliny the Elder, writing in the 1st century AD, recorded that:

-

“In Italy also, there are walls of brick, at Arretium (Arezzo) and Mevania” (‘Natural History’, 35:49)

In fact, by the time that Pliny was writing, Bevagna had stone walls, but he could have been relying on information about an earlier circuit in brick that has not survived. Two facts give Pliny’s account credibility:

-

✴as we shall see, local clay deposits in the area were exploited in the 2nd century BC, which suggests that brick manufacture would have been feasible here from an early date; and

-

✴traces of brick walls from the 3rd century BC have (apparently) been discovered at Arezzo.

Colonisation of Spoletium (241 BC)

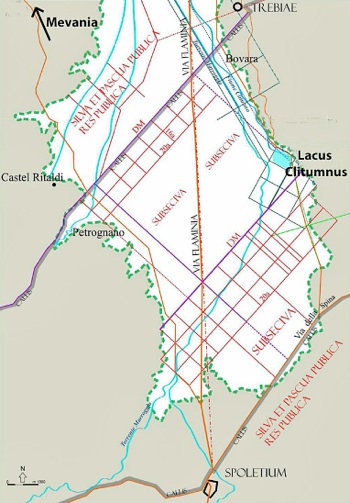

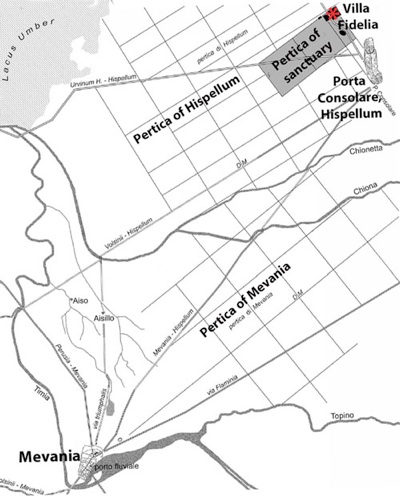

Pertica of Spoletium

Adapted from Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, Figure 2)

According to Velleius Paterculus (ca. 19 BC - 31 AD):

-

“Spoletium [was formed] three years [after the consulship of Torquatus and Sempronius, [i.e. in 241 BC], in the year in which the Floralia were instituted [at Rome]” (‘Roman History’, 1:14:8).

According to Paolo Camerieri and Dorica Manconi (referenced below, at p. 19), the new colony:

-

“... undoubtedly provided a solid base for the final Romanisation of Umbria and central Italy, which was complimented 20 years later by the construction of Via Flaminia [see below] ...” (my translation).

On the previous page, I summarised a piece of analysis by Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012), in which he assembled a body of evidence for Mevania as a major political and religious presence in the entire Valle Umbra before the conquest. However, it seems likely that, once the colony of Spoletium was formed, Mevania’s dominant position at least in the southern part of the territory would have declined.

In particular, the sanctuary at the source of the river Clitumnus and the nearby sacred grove (both described my page on the Fonti del Clitunno) passed to the new colony. Thus:

-

✴while Vibius Sequester included the “Clitumnus mevaniae” in his “De fontibus” (on river sources), which places the source of the river in the ownership of Mevania (discussed in my page on Pre-Roman Mevania);

-

✴Servius, in his commentary on a passage of Virgil’s “Georgics”, noted that:

-

“Clitumnus et deus et lacus in finibus Spoletinorum” (“Commentary’, 2:146)

-

“Clitumnus, [its] deity and [its] lake (presumably references to the sanctuary of the deity at the source of the river) are in the territory of Spoletium” (my translation).

Thus, in the diagram illustrated above, which summarises the work of Paolo Camerieri and Dorica Manconi on the pertica of the colony of Spoletium, the Lacus Clitumnus can be identified at its eastern edge.

John Scheid (referenced below, at pp. 79-80) placed this apparent confiscation in a wider political context:

-

“After the definitive submission [to Rome] of the Latins in 338 BC, three important cult sites passed definitively under Roman control :

-

-the federal sanctuary of the Latins on Monte Cavo [also called Monte Albano, in the Alban Hills near Rome) was now a Roman cult site, and the Feriae Latinae were also celebrated at Rome during the federal meetings at Monte Cavo;

-

-the temple of Juno Sospes at Lanuvium [south of Rome] became a common cult site of the Romans and the Lanuvins; and

-

-at Lavinium [near modern Ostia], many annual rites were celebrated by the Lavinates and the magistrates and priests of Rome.

-

Another example is offered by the Umbrian cult site at the source of the Clitumnus ... [which was] manifestly one of the great religious sites of the Valle Umbra. ... Since it was located near Mevania, it seems likely that it was controlled by the Umbrians from Mevania itself or the surrounding area. When the Latin colony of Spoletium was founded in 241 BC, the cult site clearly passed to it, since it was later found on the boundary of the pertica of Spoletium. ... It was in this way that the Romans used the colony as an intermediary to control the places of memories and of regional reunions of the Valle Umbra” (my translation).

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, p. 95), pointed out that the cippi that had been inscribed with the so-called lex Spoletina, a law that governed the use of a wood or grove that was sacred to Jupiter, had been found:

-

“ ... immediately to the west of the Fonti del Clitunno, and can ... be identified as belonging to the sanctuary of Clitumnus ...” (my translation)

The find spots of the cippi suggest that the sacred grove was probably to the east of Castel Ritaldi, perhaps in the nearby area designated as ‘silva et pascua publica’ (public woods and pasture) in the diagram above. If Sisani is correct (which I think is likely), Mevania had originally owned what was an extended sacred area here that was transferred to the new colony of Spoletium soon after its deduction in 241 BC. In this case, the lex Spoletina would have constituted an act of Romanisation of the kind suggested by John Scheid (above).

Via Flaminia (220 BC)

The primary purpose of this road, which linked Rome to Rimini (Ariminum) on the Adriatic coast, was probably to facilitate the defence of Rome from a second Gallic invasion. However, it must have also greatly enhanced the ‘Romanisation’ of the territory through which it passed, which (as we shall see) included that of Mevania. There is some doubt about the precise date at which the road was built:

-

✴Festus recorded that it was named for Caius Flaminius:

-

“The Circus Flaminius and the Via Flaminia are named for the consul Flaminius, who was killed by Hannibal [in 217 BC] beside the Lake of Trasimene” (‘De verborum significatu quae supersunt cum Pauli epitome’, my translation).

-

This is sometimes taken to imply that Flaminius built the road when he was consul for the first time, in 223 BC. However, it seems more likely that Festus was simply using the consulship to identify Flaminius as the general who was killed at Lake Trasimene during his 2nd consulship.

-

✴Livy was more specific about the date of the road: according to the Periochae (summary) of Book 20 of his ‘History of Rome’, Flaminius built it in 220 BC, when he held the post of censor. This is the dating that I have assumed.

The road split into two branches between Narni and Forum Flaminii:

-

✴Strabo produced what is, in effect, the earliest surviving itinerary for Via Flaminia in 7 BC, but this account only mentions the western branch:

-

“The cities this side the Apennine Mountains that are worthy of mention are: first, on the Flaminian Way itself::

-

-Ocricli [Otricoli], near the Tiber;

-

-Narnia [Narni], through which the Nar River flows ... ;

-

-Carsuli; and

-

-Mevania, past which flows the Teneas (this too brings the products of the plain down to the Tiber on rather small boats);

-

still other settlements, which have become filled up with people, on account of the Way itself rather than of political organisation; these are:

-

-Forum Flaminium [Forum Flaminii]; and

-

-Nuceria [Nocera Umbra], the place where the wooden utensils are made ...” (‘Geography’, 5: 2:10).

-

✴The earliest surviving itinerary that included the eastern branch (via Spoletium) is the Itinerarium Antoninum, which was probably written in the early 3rd century AD (search this web page on ‘Flamini’)

Thus, some scholars argue that this eastern branch must have been a relatively late development.

-

✴Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 124-5) pointed out that even even Strabo’s account related to the situation some 200 years after the road’s construction. He argued that Hannibal’s march on Spoletium in 217 BC, after his victory at Lake Trasimene, would only have made logistical sense if the eastern branch of Via Flaminia had existed at that time. He therefore suggested that it was the western branch of Via Flaminia that was the later development.

-

✴In my view, the key to this debate lies in the fact that (as Strabo pointed out) Forum Flaminii owed its existence to the construction of Via Flaminia. Furthermore, it surely owed its location to the fact both its eastern and western branches met here. This suggests to me that the construction of both the eastern and western branches belonged, like Forum Flaminii, to the original project of 220 BC.

From this point, Via Flaminia formed the decumanus maximus of the city (passing along the present Corso Amendola and Corso Matteotti). It passed necropolises outside both Porta Sant' Agostino to Porta Foligno that had been in use since the 4th century BC, which suggests that it followed the route of an earlier road that had served the already urbanised society in the pre-Roman period.

Viritane Settlement (?)

Numerous inscriptions (ten of which are described in this page of the EAGLE database) indicate that Mevania was assigned to the Aemilia tribe: according to Simone Sisani, referenced below, 2007, at p. 210, Table 16), it was the only Umbrian centre with this assignation. Sisani suggested (at p. 219 and in Table 18, p. 224) that this reflected the viritane settlement of Roman veterans of Scipio Africanus here at the start of the 2nd century BC.

Sisani’s argument started with his observation (at p. 218) that establishment of a Roman prefecture at nearby Fulginia:

-

“... can be closely associated with the viritane settlement in 200-199 BC of veterans of the war against Hannibal. This is confirmed by the assignation of Fulginia to the Cornelia, ... which was probably [the tribe] of the instigator of this settlement, P. Cornelius Scipio Africanus” (my translation).

In order to substantiate his hypothesis, Sisani pointed out that, according to Livy’s account of the events of 199 BC, when Scipio Africanus held the post of princeps senatus, the praetorship of Caius Sergius Plautus was extended into the following year:

-

“... so that he might superintend the distribution of land to the soldiers who had served for many years in Spain, Sicily, and Sardinia ...” (‘History of Rome’, 32: 1: 6).

Sisani reasonably suggested that Scipio had probably arranged for Sergius’ term of office to be prorogued in order facilitate the settlement of his own veterans, and hypothesised that Fulginia’s assignation to the Cornelia tribe suggests that some of these veterans were settled here. He then suggested (at p. 219) that:

-

“... the presence of settlers in the territory of Mevania who were assigned to the Aemilia tribe can be ascribed to the same initiative. The ‘Scipian’ character of this tribe ... is evidenced by Scipio’s links to the gens Aemilia ... , [which were] established by his marriage to Aemilia Tertia, the daughter of Lucius Aemilius Paullus [before 215 BC]” (my translation).

Thus, on this model, veterans settled at Mevania were assigned to the Aemilia in ca. 198 BC. When the ‘native’ people of Mevania were enfranchised after the Social Wars, they too were assigned to the Aemilia tribe.

Popilius Cups (2nd and 1st centuries BC)

The so-called Popilius cups, which were inscribed with the Latin name of their manufacturer, Caius Popilius (CIL XI 6704) and their places of manufacture, Mevania and Ocriculum (Otricoli) , were widely spread throughout Etruria. It seems likely that Caius Popilius was a Latin-speaking migrant who was attracted by the clay deposits at Mevania and by the transport links offered by Via Flaminia and by the port on the Tiber at Ocriculum. Two examples are illustrated in the catalogue edited by L. Agostiniani et al. (referenced below, respectively entries 80 and 81):

-

✴One from Cerveteri, which is now in the Museo Nazionale Etrusco di Villa Giulia, Rome, has the inscription:

-

C POPILI/ OCRICLO

-

✴One from Corchiano (near Viterbo), which is now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (exhibit 95.59), has the inscription:

-

C POPILI/ MEUANIE

Other Popilius signatures are illustrated in the article by André Baudrillart (referenced below).

Magistracies after the Conquest

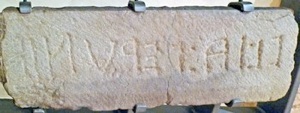

ST Um 25: pe. pe. uferier uhtur

Mevania’s probable treaty with Rome would have allowed for its nominal independence, with its internal affairs governed by its own magistrates. Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007 at pp. 249-51) assembled the epigraphical evidence for his assertion that:

-

“The administrative structure of the federated communities of Umbria appears to have been based on a college of four members, comprising two pairs of magistrates: the auctores and the marones” (my translation of the opening sentence on p. 249).

The auctores seem to have been the senior pair of magistrates, while the marones were more frequently attested because they were responsible for public works that were often accompanied by inscriptions. Two inscriptions from Mevania formed part of Sisani’s analysis:

-

✴An inscription (ST Um 25) on a fragment of a sarcophagus cover (2nd century BC, illustrated above), which uses an Etruscan alphabet, reads:

-

pe. pe. uferier uhtur

-

It thus commemorated Petro Aufidius, son of Petro, who held the post of “uhter” (equivalent to Sisani’s Latinised auctor). This inscription came from the area of Mevania but was sold on the open market and is now in the Museo Archeologico of Gubbio. It is discussed further below in the context of a putative ethnic revival at Mevania in the late 2nd and early 1st centuries BC.

-

✴A now-lost Augustan inscription (AE 1965, 279a), which came from Montefalco, commemorated a quattuorvir (almost certainly of the municipium at nearby Mevania) who also held the post of marone. The word ‘marone’ was used here anachronistically, and probably represented an antiquarian restoration of the original magistracy at Mevania, now applied to a non-civic (probably religious) function (as discussed below). (I have included it in this section for completeness.)

Social War (ca. 90 BC)

After the Social War, the people of Mevania (like those of the other previously federated communities of Umbria) received Roman citizenship. Mevania was assigned to the Aemilia tribe, as evidenced, for example, by a funerary inscription (AE 1987, 0346, late 1st century BC) that was discovered in 1985 in the necropolis of Colle San Lorenzo (now in the Museo Archeologico), which commemorates:

Sex(to) Baebio Sex(ti) f(ilio) Aem(ilia).

As noted above, no other Umbrian municipium was assigned to this tribe, and it might well have reflected the already-existing assignation of the descendants of viritane settlers at Mevania from perhaps a century earlier.

The original walls of Mevania seem to have been rebuilt in stone in the early 1st century BC, perhaps at the time of municipalisation. Traces of this circuit survive in the east and west sections of the present city walls.

Ethnic Revival in ca. 100 BC ?

Revival in the use of the Umbrian Language

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 286) pointed out that:

-

“In the late 2nd and early 1st centuries BC, the epigraphic record seems to point to a second flowering in the use of the Umbrian language, which was employed in four inscriptions from Mevania [below] and in the segment Va-b7 of the ‘Iguvine Tables’ of Gubbio” (my translation).

He suggested (at p. 288) that this should be placed in the context of the agrarian reforms proposed at Rome in the late 2nd century BC, which threatened the interests of municipal élites and perhaps fostered an increase in their desire to reaffirm and manifest pride in their ethnic identities (a process that is often associated with the outbreak of the Social War in 90 BC).

These four inscriptions from Mevania fall into two groups:

-

✴Three of them are funerary inscriptions that employed an Etruscan alphabet. They are, in fact, three of only seven known funerary inscriptions that were (or possibly were) in the Umbrian language. (The other four, which are from Tuder (Todi), use the Latin alphabet. Simoni Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 287, note 52) suggested that these did not belong in the corpus of Umbrian inscriptions.)

-

✴The fourth (which is on a sundial) commemorates two men who held a public office that might suggest a revival of ancient ceremonial.

These four key inscriptions are discussed in turn below. The numbers in square brackets in the respective section headingsrelate to the entry on each inscription in the catalogue edited by Luciano Agostiniani (referenced below).

Inscribed sarcophagus cover from Bevagna (2nd century BC) [50]

This funerary inscription (ST Um 25), which was discussed above in the context of the magistracies at Mevania, commemorates:

pe. pe. uferier uhtur

This man, whose name can be Latinised as Petro Aufidius, son of Petro, held the post of “uhter” (senior magistrate) in the pre-municipal administration. As noted above, the use of the Umbrian language and an Etruscan alphabet seems to reflect a deliberate antiquarianism. This is reflected in the design of the sarcophagus: according to Giulio Giannecchini (in entry [50]), it recalls Etruscan funerary practice of the 4th and 3rd centuries BC.

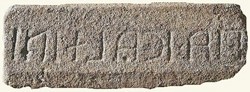

Funerary Inscription (ca. 100 BC) [51]

This inscription (ST Um 26) is on the lid of a cinerary urn that was found recently in Vecciano, outside Montefalco (and is now in the Museo Civico there). It reads:

vi: ia: perunia

The name of the deceased can be Latinised as Vibius Perunia, son of Ianto.

Inscribed cover of a cinerary urn (ca. 100 BC) [52]

This inscription (ST Um 26) is on the cover of a cinerary urn that was found in the Fabbrica necropolis of Mevania (and is now in the the Museo della Città, Bevagna). It reads:

vi(pi) ia kaltini

The name of the deceased can be Latinised as Vibius CalTinia, the son of Ianto.

Lid of a cinerary urn (late 2nd century BC)

We might usefully compare the three funerary inscriptions above, which are all in the Umbrian language, with the Latin inscription (CIL XI 5107): it is on the lid of a travertine cinerary urn on which the deceased reclines, which was probably made in Perusia (Perugia). The lid, which is from an unknown location in Bevagna, is now embedded in the interior wall of the Museo Archeologico, Bevagna. The inscription commemorates:

C(aius) Laaro V(ibii) f(ilius) T(iti) n(epos)

Caius Laaro, son of Vibius, grandson of Titus

Although this inscription is in Latin, it is perhaps significant that the urn (like the sarcophagus of pe. pe. uferier above) reflects Etruscan (in this case, Perusian) rather than Roman funerary practice.

Sundial from Bevagna (ca. 100 BC) [36]

The fourth of Sisani’s late Umbrian inscription (ST Um 8), also uses an Etruscan alphabet,. It is found on this lovely limestone sundial, which was ploughed up in 1969 near the tabernacle of the Madonna del Core, outside Porta Cannara, and which is now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Perugia. It reads:

[-.] p. nurtins.ia.t.ufeřie[r]

cvestur farariur

The names of these two individuals are interesting:

-

✴The name of p. nurtins can probably be Latinised as Publius Nortinus. As discussed further below, this family is documented in other inscriptions from Mevania and also in inscriptions from the Etruscan city of Volsinii (Bolsena). The family name probably derives from that of the Etruscan goddess Nortia.

-

✴The name of ia.t.ufeřie[r] can probably be Latinised as Ianto Aufidius, son of Titus.

-

•The same family name appears in the inscription (ST Um 25) above, which commemorates the uhter, pe. pe. uferier.

-

•The Latin version of this name is known in two other inscriptions from Bevagna (CIL XI 7940 and CIL XI 5040), both of which date to the 1st half of the 1st century AD.

Nortinus and Aufidius held the post of ‘cvestur farariur’: the first word the first word is probably equivalent to the Latin word ‘quaestors’,, while the second suggests responsibilities that were related in some way to the supply of spelt. Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 422) suggested that their function was probably analogous to that of the “homons dur puri far eiscurent” (two men who come to fetch the flour) who appeared in Table Vb of the Iguvine Tables from Gubbio (mentioned above):

-

“The unique title [‘cvestur farariur’’ on the sundial from Mevania] finds a perfect parallel in the ‘homons pure dur to eiscurent’ [of Iguvium, who were] in charge of the collection of the tribute in flour offered by the participating districts during the so-called ‘ceremony of the tenths’, which constituted an expression of political and religious solidarity of the various people that belonged to the [so-called] Iguvine League” (my translation).

The implication is that the inscription on the sundial suggested that Mevania was at the heart of a similar communal ritual.

The find spot of the sundial was on the road from Mevania to Perusia. This road passed through Ospedalicchio (some 20 km north of Bevagna and 10 km west of Assisi), which was the find spot of a possibly related Umbrian inscription (which is also in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Perugia). This inscription (ST Um 10), which was broadly contemporary with that on the sundial (although it uses the Latin alphabet), referred to a acred field that had been bought and delimited for a religious purpose:

AGER EMPS ET TERMNAS .... SACRE STAHU

It took place during the period of office of:

-

✴the two men who held the post of uhter in the year in question:

-

•C(aius) Vestinius, son of V(ibius) and

-

•Ner(o) Babrius, son of T(itus); and

-

✴the two men who held the post of marone:

-

•Vois(ienus) Propartius, son of Ner(o); and

-

•T(itus) Voisienus, son of V(ibius).

Although the find spot ST Um 10 came from a location of the periphery of Asisium, it was certainly linked to that city: the uhter Nero Babrius, son of Titus had the more junior post of marone in the (presumably earlier) Latin inscription (CIL XI 5390) that related to a major construction project there. Thus, it records an ‘official’ project that carried the imprimatur of the magisterial college of Asisium (even if the names of the current magistrates appeared here only as a very elaborate dating device). Simoni Sisani (referenced below, 2012, pp. 422-3) proposed that the ‘cvestur farariur’ of ST UM 8 (above) were federal quaestors, and that:

-

“The chronological accord between [ST Um 8 and 10] makes it highly probable ... [that] the ager in the latter was the one specifically for the cultivation of sacred spelt that was offered by Asisium on the occasion of communal celebrations of the Umbrian League (my translation).

He explained (at p. 422) that the ritual would have been:

-

“... designed to seal the various components of the [Umbrian] federation on the basis of ethnicity, [as was the case in the] analogous ritual on Monte Albano celebrated by the people of the Latin League” (my translation).

These two inscriptions (ST Um 8 and 10) clearly represent the late use of the Umbrian language in the Valle Umbra at a time when Latin was taking the place of Umbrian, at least in public inscriptions. It is certainly possible (as Simone suggested) that:

-

✴given their find spots, they were related to each other; and

-

✴their content suggests that they related to a ceremony similar to the ‘ceremony of the tenths’ recorded in the broadly contemporary Table Vb of the Iguvine Tables, they related to a.

However, I see two main difficulties with the further hypothesis that these were the well-remembered rituals of an ancient ‘Umbrian league’:

-

✴With the exception of ST Um 10, the epigraphic evidence for Asisium at this time (including CIL XI 5390, above), points instead to a precocious ‘Romanisation’ of Asisium, as discussed in my page of the Ancient History of Asisium. Thus, for example, Filippo Coarelly (referenced below, 1991) entitled his paper of the subject:

-

"Assisi Repubblicana: Riflessioni su un Caso di Autoromanizzazione".

-

This does not invalidate the hypothesis of a the revival of an ancient communal ritual in the Valle Umbra, but it does make it difficult to understand the forces that might have caused the people of Asisium to take an active part in it.

-

✴The ‘league’ described in the Iguvine Tables seems to have involved only the districts that later coalesced at Iguvium. It certainly excluded at least one of the neighbouring communities: the ‘Tadinates’, who later coalesced at nearby Tadinum (Gualdo Tadino), were listed among the inveterate and hated enemies of the Iguvines. Thus, if the ritual described in these Tables is accepted as a precedent for a similar ritual in the Valle Umbra, the implication would be that the field at Ospedalicchio was remembered as having originally belonged to a district of Mevania, rather than to an autonomous member of an ‘Umbrian League’.

In short, if ST Um 8 and 10, taken together, are accepted as evidence for the revival of an ancient Umbrian ritual in the Valle Umbra, it is likely that this revival took place under the auspices of Mevania, and that Asisium played a willing but peripheral role in it. There is no evidence that any other Umbrian city participated in it.

Links with Volsinii

The following sections consider the surprisingly strong epigraphic evidence for a link between Mevania and the Etruscan city of Volsinii (Bolsena) in the late Republic.

Members of the gens Nortia

As noted above, p. nurtins (whose name can probably be Latinised as Publius Nortinus) was commemorated in an Umbrian inscription (ST Um 8) of ca. 100 BC. This family name is known from:

-

✴two Latin inscriptions from Mevania:

-

•a funerary inscription (AE 1991, 0636) from the necropolis at Collepoppo (now in the Museo Archeologico) which dates to the 2nd half of the 1st century BC, and which commemorates a freedman of Caius Nortinus; and

-

•another (now-lost) funerary inscription (CIL XI 7949) from an unknown location in Bevagna, which also dates to the 2nd half of the 1st century BC and which commemorates Nortina, the daughter of Titus; and

-

✴two inscriptions from Volsinii (Bolsena):

-

•a cippus (date ??) from an unknown location probably in or near Bolsena, published by Alessandro Morandi (referenced below, at pp. 78-80), which has an Etruscan inscription that commemorates Avle Nurtins; and

-

•a (now-lost) inscription (CIL XI 2690) from an unknown location in Bolsena (date ??) that commemorates Caius Callius Nortinus.

This link with Volsinii suggests that the name of the gens Nortina derives from that of the Etruscan goddess, Nortia, whose particular links with Volsinii are well-attested. It is possible that a branch of this family moved from Volsinii to Mevania, perhaps after 264 BC, when the Romans destroyed ‘old’ Volsinii and moved most of its surviving population to a new settlement on the shores of Lake Bolsena.

Repentina at Hispellum

This funerary inscription (CIL XI 5334)was found at an unknown location in Spello, is relevant: it is now lost, but Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1998, p. 469) published a photograph. It read:

[R]epentina / [N]ortiaes / ancil(la)

It has been variously dated to:

-

✴the 1st century BC, by Luigi Sensi (referenced below, at p. 468);

-

✴the late Republic, by Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 426, note 97); and

-

✴the second half of the 1st century BC, in the EAGLE database (see the CIL link above).

The inscription thus commemorates a lady called Repentina, who was a slave of [N]ortiaes:

-

✴If this suggested completion is correct, she was a slave of the cult of Nortia, which would suggest that there was a cult of the Volsinian goddess Nortia at Hispellum. This too could suggest that some people from ‘old’ Volsinii had settled in the Valle Umbra in 264 BC rather than moving to Lake Bolsena.

-

✴However, this completion is not beyond doubt, and Reptina might, alternatively, have belonged to a lady called Ortia or Hortia.

Aulus Rubrius

An inscription (AE 1947, 0063), which was reused in the church of San Vincenzo, Bevagna and which is now in the Museo Archeologico, reads:

A(ulus) Rubr[ius - f(ilius)]

harispẹ[x]/ Volsiniensi[s]

s(enatus) c(onsulto)

The local senate had decreed the posting of this inscription in honour of Aulus Rubrius, a haruspex (a priest who read the future by examining the entrails of sacrificed animals) who was associated in some way with Volsinii. The inscription has been variously dated to:

-

✴the late Republican period, by Laura Bonomi Ponsi (in A. Feruglio et al., referenced below, pp. 86-7; entry 2:122), in the light of its epigraphy and the absence of a cognomen;

-

✴the early 1st century BC, by Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 503); and

-

✴the second half of the 1st century BC, in the EAGLE database (see the AE link above).

Laura Bonomi Ponsi (as above) pointed out that the name Rubrius is known from at least three other inscriptions from Mevania (CIL XI 7953, CIL XI 5068 and CIL XI 5041) but is not known in Volsinii. She therefore suggested that Aulus Rubrius probably came from Mevania and that he had been instructed in the art of haruspicy at Volsinii. Jean MacIntosh Turfa (referenced below) reported a similar opinion in her review of a book by Marie-Laurence Haack (referenced below), which I have not been able to consult directly:

-

“[Some] men seem to have recognised the cachet of Etruscan religious expertise, such as A. Rubrius (no. 79), an Umbrian who styled himself ‘Volsiniensis’ in the 1st century BC. [Haack] suggests that this expressed his having trained at Volsinii, presumably the [leading centre] of Roman religious academe [at that time], and that this is our earliest instance of an Etruscan office translating to an Italian/Roman position.”

Laura Bonomi Ponsi (as above) suggested more specifically that Aulus Rubrius had belonged to a ‘collegium haruspicum Volsiniensium’. Francesco Roncalli (referenced below, at p. 230) also felt that the title ‘harispex Volsiniensis’ had an official air about it, and wondered whether Aulus Rubrius had been:

-

“... one of the sacerdotes [priests] recorded in the [much later] Rescript of Constantine [CIL XI 5265, ca. 335 AD] from Spello, which recorded that priests who were elected [annually or in alternate years] in order to represent the Umbrians, collectively, in annual celebrations held apud [at or near] Volsinii” (my translation).

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 503) agreed:

-

“... we could be dealing, not with a migrant from Volsinii nor with a local man who was educated there, but rather with one of the sacerdotes [priests] recorded in the Rescript of Constantine, who were elected by the Umbrians to participate in the ceremonies in the fanum Voltumnae. [Note that the Rescript does not actually mention the the fanum Voltumnae: it simple says that these meetings of the 4th century AD were held apud Volsinii]. The dating of the inscription [of Aulus Rubrius] is extremely significant: it testifies to the vitality of these ceremonies even at the start of the 1st century BC, at the time of the first monumentalisation of the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia [below] and the political career of Lucius Falius Tinia [below]” (my translation).

He expressed the same opinion a later paper (referenced below, 2012, at pp. 426-7):

-

“[The title ‘harispex volsiniensis’] demands to be understood as that of an Umbrian sacerdos [priest] expressly appointed to conduct his activities at Volsinii. [This] allows us to postulate the direct involvement of the community in the pan-Etruscan celebrations of the fanum Voltumnae” (my translation).

I discuss the relevant part of the Rescript of Constantine below. For the moment, I simply point of that nothing in the text of the Rescript suggests that the Umbrian priests who travelled to Volsinii each year were or ever had been haruspices. I think that the simpler explanation is more likely: that Aulus Rubrius, a native of Mevania, was esteemed in his native city because he had trained in haruspicy in what must have been the prestigious centre for such training at Volsinii.

Lucius Falius Tinia

Simone Sisani (2002, referenced below) published a detailed paper on a now-lost inscription (CIL XI 5281) on a funerary stele that was found in 1773. It read:

L(ucius) Falius L(uci) f(ilius) Tinia

cens(or), pr(aetor) bis, IIIIvir

There has been some confusion in the past as to the find spot of this stele:

-

✴At the time of his paper of 2002, Sisani believed that it had been found near the church of Santa Luciola, outside Spello. He therefore suggested that Falius had been a quattuorvir of Hispellum (which he assumed had had municipal status before its colonisation in ca. 40 BC, as discussed below).

-

✴However, in his paper of 2012 (referenced below, at p. 425, note 90), he revised this: the find spot was, in fact, near the present railway station of Cannara (as indicated also in the EAGLE database). Thus, the inscription was found at a location that was roughly midway (as the crow flies) between Spello and Bevagna, a fact that led the EAGLE database to designate it as ‘Hispellum?/Mevania?’.

The dating of the inscription is uncertain:

-

✴Since Simone Sisani assumed in his paper of 2002 that Falius had been a quattuorvir of Hispellum, he dated the inscription to the period after municipalisation but before colonisation (after which time Hispellum was securely administered by duoviri). More specifically, he suggested (at pp. 504-5) that Falius had probably been a member of the first college of quattuorviri after municipalisation in ca. 90 BC, and that he had been responsible for the first municipal census. By the time of his 2012 paper (referenced below, at p. 425, note 90), he had been able to confirm this dating on paleographic grounds by examining a photograph (illustrated as his Figure 10) that had been taken in the 1980s, when the inscription had been in the deposit of the Commune.

-

✴However, the EAGLE database (see the CIL link above) gives a wider range of dates, within the period 90-30 BC.

This situation leads to some doubt as to whether Falius had been a quattuorvir of Hispellum or of Mevania:

-

✴If one assumes (with Sisani) that Hispellum enjoyed municipal status in the period ca. 90-40 BC and that the inscription belongs to this period, then Falius could have been a quattuorvir of Hispellum or Mevania.

-

✴If one assumes (with Filippo Coarelli, referenced below, 2001, at pp. 47-8) that Hispellum was a vicus of Mevania (rather than an autonomous municipium) before colonisation, then Falius must clearly have been a quattuorvir of Mevania.

(For the reasons set out in my page on Mevania after the Perusine War, I think that the balance of probabilities lies with the second of these propositions.)

It is interesting to note (in the context of the presumed links between Mevania/ Hispellum and Volsinii discussed above) that Lucius Falius Tinia possibly had Etruscan origins: Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 39) was strongly of this opinion:

-

“The Etruscan derivation [of the name ‘Falanius’, used in the ‘Annals’ of Tacitus] is clear: as witness, L. Falius Tinia [of CIL XI 5281], who carries for cognomen the name of the supreme [Etruscan] deity.”

Supreme Priest of an Umbrian Federation (?)

The post of praetor, which Lucius Falius Tinia held on two occasions, is problematic. Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 489) pointed out that it was unlikely to have been a civic post in a municipium at this time, and therefore reasonably suggested that it was more probably a priesthood. He cited inscriptions from other municipia in which this was more clearly the case, including CIL XI 4189 (from Interamna Nahars, modern Terni and dated to the Augustan period), which commemorated Titus Pinarius Natta and his father, Titus Pinarius, each of whom had held the post of quattuorvir and the clearly religious post of praetor sacrorum.

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 503) then developed his analysis in the light of his conviction that Mevania was the capital of an Umbrian Federation that had its federal sanctuary at what is now Villa Fidelia (see below). In this context, he suggested that:

-

“... the post of praetor held by Lucius Falius Tinia possibly maintains the memory of the supreme ... magistracy [of the Umbrian Federation]. This use of the title ‘praetor’ as a Latin interpretation of the Umbrian federal magistracy - of which the original [Umbrian] name does not survive - finds ... confirmation in the analogous case of the praetores of the Etruscan federation” (my translation).

In order to elaborate this last point, Sisani referred (at p. 504) to the inscriptions (1st century AD) known as the ‘elogia Tarquiniensia’, which record the careers of members of the Etruscan Spurinna family, two of whom (Velthur, son of Lars and Aulus, son of Velthur) had each held a post on more than one occasion in the 5th-4th centuries BC that was rendered into Latin in the inscription as ‘pr(aetor)’. Sisani argued (following Mario Torelli, referenced below) that:

-

✴the descriptions of the careers of these men in the ‘elogia Tarquiniensia’ showed that they had each served as the supreme magistrate of the Etruscan Federation; and thus

-

✴the word ‘praetor’ in these inscriptions was the Latin rendition of the original Etruscan title of this magistracy (often given in Etruscan as ‘zilath mechl rasnal’).

This Latin form had certainly been used been used for the annually elected priests of the Etruscan Federation after its revival in the Augustan period: numerous surviving inscriptions show that the full title of this priest was praetor Etruriae XV populi. Sisani argued that:

-

“It is absolutely probable that this ... [usage was inspired by the Latinised form of the title that had been] conserved in the memories of the prestigious Spurinna of Tarquinia. The name of this Roman magistracy is indeed the one that most naturally serves to define the supreme magistracy par excellence [i.e. that of the Etruscan Federation]” (my translation).

He then developed this argument to include the priesthood in Umbria as follows:

-

“The way in which the usage of the word ‘praetor’ developed [in Etruria]:

-

-from the [Latinised title of the] supreme political leader of in the ‘elogia Tarquiniensia’; to

-

- praetor Etruriae XV populi [of the revived Etruscan Federation in the Augustan period];

-

can ... illuminate the less well known development of the praetores of Hispellum, whose posts we only come across at the time of municipalisation, when the Umbrian praetor probably had as his only role that of [presiding over ?] the common rites of the [Umbrian] nomen at the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia” (my translation).

-

I have two main reservations about Sisani’s hypothesis that the title ‘praetor’ in CIL XI 5281 indicates a federal priesthood:

-

✴As note above, it rests on another hypothesis that was first proposed by Mario Torelli (referenced below): that both Velthur I and Aulus Spurinna had achieved the military successes described in the ‘elogia Tarquiniensia’ while serving as the ‘zilath mechl rasnal’ (the supreme magistrate of the Etruscan Federation, which was assumed to have been rendered in Latin in the inscription as ‘pr(aetor)’). However, this hypothesis is not universally accepted. For example, Tim Cornell (referenced below, at pp. 170-1) insisted that the engagements described in the inscription were most unlikely to have been federal in nature. In fact, as he observed:

-

“... there is no historically verified instance in the literary sources of positive operations by a federal army organised by the Etruscan league.”

-

If Cornell’s scepticism is justified (and thus, if the praetores Velthur I and Aulus Spurinna cannot be securely placed in federal context), then our earliest evidence for a securely federal Etruscan praetor relates instead to Sextus Valerius Proculus from Vettona (Bettona), who is recorded as a pr(aetor) Etruriae of the revived Etruscan Federation in the early 1st century AD in two inscriptions (CIL XI 7979 and AE 1996, 653b). This late example is clearly of no help in providing a precedent for the title of supreme magistrate of the putative Umbrian League in the Republican period.

-

✴Simone Sisani (at p. 504 and note 125) did not rely entirely on Etruria for possible precedents: he asserted that the Latin word ‘praetor’ had also been applied to the supreme magistrates of the Latin, Marrucinian and Gallic leagues. He did not provide references, and I am not equipped to comment on the strength of this additional evidence. However, he also cited (at pp. 488-9 and note 31) a number of inscriptions from Italian municipalities and colonies in which the title ‘praetor” had denoted priesthoods without any federal connotations. (These included the praetores sacrorum from Interamna Nahars in CIL XI 4189). However, we might follow the reasoning of Tim Cornell here:

-

•Tim Cornell (referenced below, at p. 171) pointed out that:

-

“Velthur I and Aulus Spurinna are referred to [in the ‘elogia Tarquiniensia’] simply as 'pr(aetores)'. ... If they were federal magistrates, why are they not described as such in the texts [using a specific title such as praetor populorum Etruriae] ?”

-

•We might similarly ask:

-

“If Lucius Falius Tinia was the supreme magistrate of an Umbrian Federation, why was he described in CIL XI 5281 simply as ‘praetor’, rather than as ‘praetor populorum Umbriae’?”

Conclusions

It seems to me that we all we can reasonably assume is that:

-

✴Falius’ funerary inscription can probably be assigned to the period 90-30 BC, and it might (as Sisani suggested) belong in the early part of this period;

-

✴If one assumes that Hispellum was a municpium prior to colonisation, the Falius could have held his civic posts at either Hispellum or Mevania. However, if one follows Filippo Coarelli (above) in assuming that Hispellum was simply a vicus of Mevania prior to colonisation, then he clearly held these posts at Mevania.

-

✴Falius was additionally twice elected to what was probably the priestly post of praetor. However, there is no firm basis for establishing the nature of this putative priesthood, and there is nothing to suggest that it was in any sense “federal”. It could have been associated in some way with the sanctuary at the Villa Fidelia (below), but we have no evidence for this.

Monumentalisation of the Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia (?)

Locus sacer at Villa Fidelia

Adapted from Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, Figure 13)

See also, for example, Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, 2012, Figure 16)

As set out in my page on Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia before 41 BC, an analysis of the evidence for the Roman centuriation of land between Bevagna and Spello reveals an anomalously-oriented rectangle of land near Villa Fidelia, below the walls of Spello. Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 430) pointed out that:

-

“... the new land division [at Hispellum at colonisation] ... had evidently preserved and surrounded [this] undivided land, which had previously been assigned to an ancient sanctuary [evidence by sporadic finds here]. This enclave thus maintained its quality as a locus sacer [sacred place], along with its original orientation, which had been established in a previous programme of centuriation ...” (my translation).

Sisani (as above) then drew the following conclusion:

-

“The coherence between [the orientation of the land belonging to] the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia and the centuriation of Mevania obviously indicates that:

-

-the sanctuary had originally belonged to Mevania; and

-

-it was transferred to Hispellum ... only at the moment when the colony was formed” (my translation).

As Sisani pointed out, the centuriation of Mevania cannot be dated with certainty to the period before municipalisation (i.e. before ca. 90 BC). Thus, there is no hard evidence for the ownership of the locus sacer before this period. However, the fact that it escaped veteran settlement in 41 BC probably indicates a long and venerable history. Sisani reasonably assumed that it had achieved this status in the ownership of Mevania, rather than in the ownership of the less important centre at pre-colonial Hispellum.

Monumentalisation in the Late Republic (?)

Manconi, Camerieri and Cruciani (referenced below, at p. 389) reported that emergency excavations carried out in 1990 at the southwest edge of the site of the Augustan theatre (see below) had:

-

“... brought to light architectural terracottas of the 2nd-1st centuries BC, as well as other finds that support the hypothesis of the presence [here] of an ... Italic sanctuary” (my translation).

Unfortunately, these finds were never published, and the information above is all we have (as far as I know). Simoni Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 288) concluded from this evidence that:

-

“At Hispellum ... we witness, in the last years of the 2nd century BC, the first monumentalisation in the Hellenistic style of the suburban sanctuary at Villa Fidelia, which can be identified as the religious sanctuary of the [Umbrian] League. This constitutes the Umbrian parallel to the contemporary monumentalisation of the most important sanctuaries in Lazio and the Italic regions. ...” (my translation).

It is certainly true that these (sadly unedited) finds could constitute evidence for the construction of one or more cult sites in an ancient sanctuary here , and that this could have formed part of the putative ethnic revival discussed above. However, it seems to me that they do not, on their own, constitute evidence for a major monumentalisation of the site in the late 2nd century BC, on the scale, for example, of the well-attested programme at the ethnic sanctuary at Pietrabbondante. Thus, they do little to support the hypothesis that the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia belonged to an Umbrian League.

Temple of Minerva near Villa Fidelia

Manconi, Camerieri and Cruciani (referenced below, at p. 390) reported that a large number of blocks and other elements had been excavated at an unknown time beside a well that was located between the Villa Fidelia and the nearby Chiesa Tonda. They observed that these remains were:

-

“...certainly relevant to the structure of the sacred complex [at Villa Fidelia]” (my translation);

and noted (at note 53) that they had recently been laid out there. Linda Baiolini (referenced below, at p. 117) specified that they were in the ‘galoppatoio’ of Villa Fidelia (as illustrated above), and that they comprised:

-

“... 32 large blocks, half made of white limestone and the other half of travertine, at least four of which shared the same kind of moulding, perhaps belonging to the cornice of a podium” (my translation).

Linda Baiolini (as above) also suggested that the find spot of these remains might also have been the original find spot of an inscription that was recorded by Fausto Gentile Donnola in the 17th century as follows:

-

“In the convent of the Madonna del Vico, there is a small square stone that was found in 1615, not far from that church [now known as the Chiesa Tonda]” (my translation).

It is clear from Donnola’s transcription that he referred to CIL XI 5263:

[Ser]venius |(mulieris) l(ibertus) Chilo

aedem Minerv(ae) opere

[tec]t(orio) camera(m) limi[na]

[l]api(de) rub(ro) asseres

...m cludend(am)

f(acienda) cur(avit)

The inscription, which passed to the collection of Ludovico Jacobilli and is now in the Museo Archeologico at Palazzo Trinci, Foligno, records a temple of Minerva that had been [built? restored?] in local ‘pietra rossa’ (pink stone) by Servenius Chilo, the freedman of a lady. The inscription has been variously dated:

-

✴to the late Republican period, before (perhaps only slightly before) the colonisation of Hispellum in 41 BC, by Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2102, at p. 424-5);

-

✴between the late 1st century BC and the early 1st century AD, by Paola Bonacci and Sabina Guiducci (referenced below, at p. 259); and

-

✴27 BC - 14 AD (i.e. during the the reign of Augustus), in the EAGLE database (see the CIL link above).

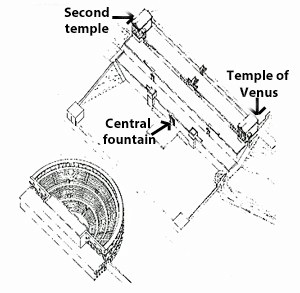

Reconstruction of part of the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia in the imperial period

From Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, 2010, Figure 15)

With kind permission of the authors

Paolo Camerieri and Dorica Manconi (referenced below, 2012, at p. 71, note 22) tentatively suggested that:

-

“The use of ‘pietra rossa’ in this temple [as evidenced by CIL XI 5263], as in the Temple of Venus from the Augustan period, and the nearness of the place of recovery of the inscription to [the present Villa Fidelia], suggests that it might be identified as the twin temple on the second terrace there” (my translation).

Linda Baiolini (as above) also suggested that, if one accepts that the blocks in the ‘galoppatoio’ and the inscription came from the same place:

-

“One can ... think that [they are all] related to the temple that is symmetrical with the one that is dedicated to Venus at Villa Fidelia” (my translation).

The plan above, which reconstructs the appearance of the complex after its reconstruction in the early Augustan period, shows these two locations at this later date:

-

✴The ‘Temple of Venus’ stood on the site of an earlier temple of unknown dedication, which had been restored and dedicated to Venus soon after colonisation (as evidenced by the inscription CIL XI 5264), shortly before its rebuilding in the early Augustan period.

-

✴Its twin, which is marked ‘Second temple’ in the plan, is presumed to exist under the present Villa Fidelia, in view of the marked symmetry of the complex in its Augustan form. However, we have no archeological evidence of its existence.

Thus Camerieri and Manconi, followed by Baiolini, suggest that this second temple might be tentatively identified as the temple of Minerva, which was built/restored by Servenius Chilo at some time in the late Republican or the Augustan period. However, given the uncertainty that surrounds:

-

✴the original locations of both the inscription and the remains of a temple in the ‘galoppatoio’; and

-

✴the possible date and form of the putative temple under Villa Fidelia;

all that can be said with confidence is that the inscription and the remains of a temple in the ‘galoppatoio’ probably related to one or more temples in or near the sanctuary.

According to Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, p. 501), the dedication to Minerva in CIL XI 5263:

-

“... seems to allude to the existence of the cult of Nortia at Hispellum, which everything suggests was officiated at the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia ... , [particularly since the inscription was found] near the sanctuary ...” (my translation).

It is certainly true, as Sisani pointed out, that Nortia and Minerva were both associated with the rite of the clavus annalis, (at Volsinii and Rome respectively) and that a cult of ‘Minerva Nortina’ is recorded at Visentium (Bisenzio, on Lake Bolsena) in AE 1962 0152. Nevertheless, I can see no basis for the assumption that a temple to Minerva in or near the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia must have been linked to the cult of Nortia.

Read more:

N. Lenski, “Constantine and the Cities: Imperial Authority and Civic Politics”, (2016) Philadelphia

M. Ricci, “Praetores Etruriae XV Populorum: Revisione e Aggiunte all’ Opera di Bernard Liou”, Bollettino della Deputazione di Storia Patria per l’Umbria, 111:1 (2014) 5-30

P. Camerieri and D. Manconi , “Il ‘Sacello’ di Venere a Spello: dalla Romanizzazione alla Reorganizzazione del Territorio: Spunti di Ricerca ", Rivista di Antichità, 21 (2012) 63-80 W. Eck, “Administration and Jurisdiction in Rome and in the Provinces”, in

M. van Ackeren, “Companion to Marcus Aurelius”, (2012) Chichester

S. Sisani, “I Rapporti tra Mevania e Hispellum nel Quadro del Paesaggio Sacro della Valle Umbra”,, in

G. Della Fina (Ed.), “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, (2012) Orvieto (pp. 409-64)

L. Agostiniani et al. (Eds), “Screhto Est: Lingua e Scrittura degli Antichi Umbri”, (2011) Città di Castello

P. Camerieri and D. Manconi, “Le Centuriazioni della Valle Umbra da Spoleto a Perugia”, Bollettino di Archeolgic Online, (2010) 15-39

P. Bonacci and S. Guiducci , “Hispellum: La Città e il Territorio”, (2009) Spello

S. Sisani, “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

J.Osgood, “Caesar’s Legacy”, (2006) Cambridge

J. Scheid, “Rome et les Grands Lieux de Culte d’ Italie”, in:

A. Vigourt et al. (Eds), “Pouvoir et Religion dans le Monde Romain: en Hommage à Jean-Pierre Martin”, (2006) Paris, pp. 75-88

M. L. Haack, “Prosopographie des Haruspices Romains”, (2006) Pisa and Rome

J. MacIntosh Turfa reviewed this book as Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2006.12.34

L. Baiolini, “ La Forma Urbana dell' Antica Spello”, in:

L. Quilici and S. Quilici Gigli (Eds), “Città dell' Umbria”, (2002) Rome, pp 61-120

S. Sisani, “Lucius Falius Tinia: Primo Quattuorviro del Municipio di Hispellum”, Athenaeum, 90.2 (2002) 483-505

F. Coarelli, "Il Rescritto di Spello e il Santuario ‘Etnico’ degli Umbri”, in

“Umbria Cristiana: dalla Diffusione del Culto al Culto dei Santi,” Atti del XV Congresso Internazionale di Studi sull’ Alto Medioevo, Spoleto (2001) pp. 39-52

L. Sensi, “Sul Luogo del Ritrovamento del Rescritto Costantiniano di Spello”, in:

“Atti dell'Accademia Romanistica Costantiniana: XII Convegno Internazionale in Onore di Manlio Sargenti”, (1998) pp 457-77

D. Manconi, P. Camerieri and V. Cruciani, “Hispellum: Pianificazione Urbana e Territoriale”, in:

G. Bonamente and F. Coarelli (Eds),“Assisi e gli Umbri nell' Antichità” Assisi (1996) pp. 375-423; the section on the sanctuary is at pp. 381-92

F. Coarelli, "Assisi Repubblicana: Riflessioni su un Caso di Autoromanizzazione", Atti Accademia Properziana del Subasio, (1991) Assisi

F. RoncallI, “L’ Iscrizione di Amelia e l’ Epigraia Umbra Minore”, in

“M. Chiari and S. Stopponi (Eds), “Museo Comunale di Amelia: Raccolta Archeologica: Iscrizioni, Sculture, Elementi Architettonici e d' Arredo”, (1996) Perugia, pp. 227-30

A. Feruglio et al. (Eds), “Mevania: Da Centro Umbro a Municipio Romano”, (1991) Perugia

A. Morandi, “Epigrafia di Bolsena Etrusca”, (1990) Rome

R. Syme, “Names and Identities in Quintilian”, Acta Classica, 28 (1985) 39-46

T. Cornell, “Principes of Tarquinia: Elogia Tarquiniensia ... by Mario Torelli”, Journal of Roman Studies, 68 (1978) 167-73

M. Torelli, “Elogia Tarquiniensia”, (1975) Florence

J. Gascou. “Le Rescrit d' Hispellum”, Mélanges d'Archéologie e d' Histoire 79 (1967) 609-59

New Annual Festival at Hispellum

A. Baudrillart, “Coupes Signées de Popilius”, Mélanges de l' École Française de Rome, 9 (1889) 288-98

Ancient History: Pre-Roman Mevania Fonti del Clitunno

Mevania after the Conquest Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia before 41 BC Other Sanctuaries

Mevania after the Perusine War Valetudo and the Magistri Valetudinis

Return to the page on History of Bevagna.