Colonisation of Hispellum

Colonia Julia, in Hyginus’ treatise on the establishment of ‘limites’ (boundaries),

from the paper by Oswald Dilke (referenced below, p. 419)

In a momentous meeting at Bononia (Bologna) in October 43 BC, Octavian agreed with his former enemies, Mark Antony and Lepidus on the formation of a triumvirate (dictatorship of three), an allegedly temporary arrangement ahead of the expected war against the last of Caesar’s assassins (principally Cassius and Brutus). As an inducement to their soldiers to continue the civil war, they then jointly designated 18 Italian towns and cities for their settlement after the expected victory. Thus Appian recorded that, while they were still at Bononia:

-

“To encourage the army with expectation of booty, [the triumvirs] promised, beside other gifts, 18 cities of Italy as colonies - cities that excelled in wealth and in the splendour of their estates and houses - which were to be divided among them (land, buildings, and all), just as though they had been captured from an enemy in war. The most renowned among these were: Capua; Rhegium; Venusia; Beneventum; Nuceria [in Campania]; Ariminum; and Vibo. Thus were the most beautiful parts of Italy marked out for the soldiers” (‘Civil Wars’, 4:3).

Cassius and Brutus were duly defeated at Philippi in 42 BC, after which, as Josiah Osgood (referenced below, at p. 159) observed:

-

“[Mark] Antony remained to settle affairs in the east, while Octavian hurried to a terrified Italy to distribute the land promised to Caesar’s veterans.”

Laurence Keppie (referenced below, at p. 63) deduced the probable identities of the 18 towns that had been selected for veteran settlement in 43 BC: crucially for our purposes, his list included Hispellum (Spello). It has to be said that this inclusion was based only on circumstantial evidence from an autobiographical elegy by Propertius, in which the poet described his personal experience of land confiscation in the Valle Umbra and the loss of relatives in the Perusine War (41-40 BC). As Laurence Keppie (referenced below, at p. 178) observed:

-

“The Propertii of Asisium, [if one assumes that they had been] recently deprived of a substantial part of their property [for the settlement of veterans at Hispellum], are easily envisaged as supporters of ... [the rebels at] nearby Perusia.”

Thus he concluded (at pp. 178-9) that:

-

“... the misfortunes of the Propertii seem best associated with the foundation of the [colony of Hispellum], an event that may [therefore] be confidently placed in 41 BC, [shortly before the start of the war].”

Did Hispellum belong to Mevania before Colonisation?

Most of the urban settlements of Umbria (like those elsewhere in Italy) became enfranchised as municipia after the Social Wars and were thereafter administered by quattuorviri. However, the case of Hispellum is uncertain in this respect:

-

✴Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, at pp. 47-8) believed that:

-

“... the urban settlement of Hispellum assumed the dimensions and dignity of a city only with the foundation of the colony, when it first received city walls. ... The scarce remains of the settlement before then is not indicative of a city; it rather indicates a vicus, which we should recognise as a simple appendage of the [nearby sanctuary at Villa Fidelia]. This sanctuary [and, therefore, the putative vicus of Hispellum] seems to have belonged to another centre that was then more important; that is, to Mevania” (my translation).

-

✴Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 432 and note 117) agreed that the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia had probably belonged to Mevania, passing to Hispellum at colonisation (as discussed below). However, he nevertheless argued (at p. 432 and note 117) that Hispellum, like Mevania, became an autonomous municipium after the Social Wars and that it held this status until it was selected for colonisation.

The usual way of establishing that a centre had had municipal status is the presence there of epigraphic evidence for the magistracy of quattuorviri. Three surviving or recorded inscriptions of this kind could relate to quattuorviri at Hispellum in the period between the presumed establishment of the municipium in ca. 90 BC and the formation of the colony some 50 years later.

-

✴Simone Sisani (2002, referenced below) published a detailed paper on a now-lost inscription (CIL XI 5281) that was on a funerary stele that was found outside Spello in 1773. It read:

L(ucius) Falius L(uci) f(ilius) Tinia

cens(or) pr(aetor) bis IIIIvir

-

In this paper, Sisani asserted that the stele had been found near the church of Santa Luciola outside Spello, but he revised this slightly in a later paper (referenced below, 2012, p. 425, note 90): the correct location was near the present railway station of Cannara (some 6 km northwest of Spello and roughly the same distance, as the crow flies, from Bevagna). There is some uncertainty about the date of this inscription:

-

•By the time of his 2012 paper, Sisani had been able to examine a photograph (illustrated as his Figure 10) that had been taken in the 1980s, when the inscription had been in the deposit of the Commune. This examination confirmed his view of its dating to the period between the presumed municipalisation of Hispellum and its colonisation (i.e., ca. 90-40 BC). Moreover, he suggested (in the paper of 2002, at pp. 504-5) that the Falius had probably been a member of the first college of quattuorviri after municipalisation, and had been responsible for the first municipal census.

-

•The EAGLE database (see the CIL link) gives a wider range, ca. 90-30 BC. A date at the in the last decade of this range would preclude the possibility that Lucius Falius Tinius had been a quattuorvir of Hispellum.

CIL XI 5282: Titus Laterius CIL XI 5288: Lucius Turius

quattuorvir iure dicundo quattuorvir aedillis

-

✴Two other funerary inscriptions (illustrated above), both of which are now in the municipal lapidarium of Spello, commemorate quattuorviri:

-

•CIL XI 5282 (on the left), from an unknown location in Spello, which had been reused in casa Donnola at Spello, commemorates Titus Laterius, son of Titus, who had been quattuorvir i(ure) d(icundo); and

-

•CIL XI 5288, from an unknown location in Spello, which had been reused in the collegiata di San Lorenzo at Spello, commemorates Lucius Turius, son of Lucius, who had been quattuorvir aed(illis).

-

Again, there is uncertainty as to their dates:

-

•Simoni Sisani (referenced below, 2012, p. 432, note 117) dated these inscriptions to the period prior to the formation of the colony at Hispellum.

-

•The EAGLE database (see the respective CIL links) dates them to the 2nd half of the 1st century BC. If the inscriptions did belong to the late end of the range given by EAGLE, then Titus Laterius and Lucius Turius would have been a quattuorviri of Mevania.

Even if a date prior to ca. 40 BC is accepted for all three inscriptions, the evidence does not conclusively support the case for a municipium at Hispellum:

-

✴CIL XI 5281 (L. Falius Tinia) was found at a site that was roughly equidistant from Hispellum and Mevania; and

-

✴although both CIL XI 5282 (T. Laterius) and CIL XI 5288 (L. Turius) were reused in buildings in Spello, the original location of neither is known. Even if they were originally in or near Hispellum, this would not rule out the possibility that they commemorated quattuorviri of Mevania: another inscription (AE 1965, 279a) that commemorated a now-anonymous quattuorvir of Mevania in the early Augustan period was later embedded near the font of San Bartolomeo, Montefalco: if Hispellum, like the area around what is now Montefalco, had belonged to Mevania, then this could account for the presence here of CIL XI 5282 and 5288.

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 432 and note 117) offered three other pieces of evidence to support his hypothesis that Hispellum had been an autonomous municipium prior to its colonisation:

-

✴He pointed out that the tribal assignation of Hispellum (to the Lemonia) was quite distinct to that of its neighbours (including Mevania), with the implication that it must have received this assignation at municipalisation. However, as Enrico Zuddas and Maria Carla Spadonini (referenced below, at p. 57) pointed out:

-

“ ... at least nine secure epigraphic records [of this tribal assignation have been] found in the city or in its immediate surroundings. There are no known [records of this kind] before the triumviral age” (my translation.

-

They thus observed that:

-

“... on the basis of current knowledge, one cannot exclude a priori that the [assignation of Hispellum to the Lemonia] was linked to the formation of the colony” (my translation).

-

In other words, it could have belonged to Mevania and thus been assigned to the Aemilia before colonisation.

-

✴He cited Lawrence Keppie (referenced below, at p. 118), who asserted that:

-

“... in Italy, only a handful of the colonies that were established from 47 BC onwards were planted on what may be termed virgin sites, where full-scale building was a matter of some urgency”.

-

However, it seems to me that there is nothing that precludes the possibility that Hispellum was one of this handful.

-

✴He asserted that the Roman land surveyor Hyginus, in his treatise on the establishment of ‘limites’ (boundaries) of colonies:

-

“... clearly considered [Hispellum] to have existed, in both urban/territorial and institutional terms, at the time of the formation of the colony” (my translation).

-

The text of Hyginus to which Sisani referred has been translated as follows:

-

“Men of old, because of the danger of sudden outbreaks of war, were not satisfied with building walls around their cities, but also chose sites on rough and rocky high ground, where the best defence lay in the very topography of the site. Very many of the precipitous areas adjacent to these cities were not suitable for limites because of the difficulties of the terrain, and were left outside the centuriation [land division], either to provide woods for the community or, if they were barren, to lie unoccupied:

-

-the territory of neighbouring communities was granted to these cities, so that they could have an extent of land appropriate for a colony; and

-

-the decumanus maximus and kardo maximus [of the new settlements] were drawn on the best land;

-

as, for example, in Umbria, in the territory of Hispellum” (translated by Brian Campbell, referenced below, at p. 143).

-

The syntax of this passage has been much-debated, and there is no consensus as to how much of it specifically applied to Hispellum. Even if Hyginus did conceive of pre-colonial Hispellum as a walled city, it seems to me that he was not necessarily correct in this detail.

In short, the evidence is not conclusive for either hypothesis. Enrico Zuddas (referenced below) recently revisited the debate and concluded that, on the balance of probabilities, the hypothesis that:

-

“.... [Hispellum] had become a municipium after the Social War, and that it had then been transformed into a colony governed by duoviri, is a prudent choice” (my translation).

However, in my view, Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, at pp. 47-8) was more probably correct in suggesting (above) that, prior to colonisation, Hispellum was simply vicus associated with the nearby sanctuary at Villa Fidelia and that both had belonged to Mevania. After all, Simone Sisani has established that the sanctuary almost certainly belonged to Mevania before colonisation (as discussed below): this would surely have an unusual arrangement if Hispellum, which stood on the hill immediately above it, had been an autonomous municipium.

Why was Hispellum Chosen for Colonisation ?

Enrico Zuddas and Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, at pp. 57-8) pointed out that:

-

“If Appian was correct in stating [in the passage quoted above] that the cities chosen for deduction [in 43 BC] were among the most prosperous and civilised of Italy, then [Hispellum seems to have been an exception]. ... The choice of [Hispellum] for the foundation of a colony seems therefore to have been dictated by other considerations: certainly by its centrality in the [Valle Umbra] but, above all, by the presence in its immediate vicinity of the federal sanctuary of Umbria, on the site of the present Villa Fidelia” (my translation).

Zuddas and Spadoni certainly raise an important question. However, as I discuss below, while the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia was clearly important, there is no hard evidence that it was, or ever had been, the federal sanctuary of Umbria.

John Scheid (referenced below, 2005, at p. 182) was more cautious when he placed the colonisation of Hispellum in the context of Octavian’s policy of religious restoration:

-

“In order that Italy [as well as Rome] benefitted from Octavian’s restorations, he paid attention to old and important Italic sanctuaries. For instance:

-

-he transformed the grove of Feronia (Lucus Feroniae in southern Etruria) and a sanctuary of Fortune (Fanum Fortunae, Umbria) into Roman colonies;

-

-he confirmed the privileges and the autonomy of the sanctuary of of Diana Tifatina (Campania); and, finally

-

-he founded a colony at Hispellum, possibly an old federal sanctuary, and [also] gave [the new colony] responsibility for the famous sanctuary of Clitumnus.”

John Scheid (referenced below, 2006, at p. 82) expanded on his hypothesis:

-

“It should first be noted that, according to the archaeologists, the large sanctuary at [Villa Fidelia] ... could have succeeded an important supra-regional sanctuary of the Umbrians. [As in other cases], the reason for the foundation of a colony [at the relatively small urban centre here might thus have been] the presence of [this putative] renowned Italic supra-regional cult site. Unfortunately, all we know for certain at the moment is that this sanctuary had a supra-regional role in the [4th century AD, as evidenced by the Rescript of Constantine]. ... The place was clearly very important. But, what interests us more particularly was another decision of Octavian, which [was probably] taken in the same context: he gave the famous sanctuary at the source of the Clitumnus to the Hispellates. ... In other words, he confiscated this cult site from Spoletium, which had owned it since the deduction of the colony [there in 241 BC]; and perhaps he similarly confiscated a supra-regional sanctuary at Villa Fidelia to make a [new] colony and an urban centre” (my translation).

But this all begs another question: if (as I argued above) both Hispellum and the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia belonged to Mevania, a municipium that might conceivably have numbered among among “the most prosperous and civilised of Italy” at this time, why did Octavian not simply colonise Mevania if his objective was (inter alia) to secure its sanctuary? I think that the answer might lie with the fact that Mevania had an influential patron.

An Influential Patron?

A now-lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5029) from Massiccio [where is that ??] , which the EAGLE database (see the CIL link) dates to the period 50-20 BC, seems to indicate that a man called Titus Resius had been a significant benefactor of Mevania. The inscription read:

T(ito) Resio T(iti) f(ilio) Aim(ilia) / leg(ato) pro pr(aetore)

locus sepulturae ipsi / posterisq(ue) eius ob plurima

erga suos municipes / merita publice datus

This identifies Resius as a member of the Aemilia tribe, which suggests that he came from Mevania, and also as legatus pro praetore (see below). The inscription recorded that he had been given a burial site [presumably at Massiccio] for himself and his descendants in appreciation of his public services to the people of the municipium.

Maria Carla Spadoni and Lucio Benedetti (referenced below, at p. 249 and note 139), following Emilio Gabba (referenced below, at p. 103), suggested that Resius might well have delivered these services to the municipium in 41 BC, in connection with the amelioration of the threat of land confiscations. In fact, it might be possible to be more specific, if we consider his post of legatus pro praetore. This usually referred to a military officer who governed a Roman province with the magisterial powers of a praetor. However, as Joseph Solodow (referenced below, at p. 147) pointed out:

-

“... ‘praetores’ could refer to those magistrates ... who were granted imperium for the purpose of confiscating land and distributing it to veterans. It is known, for instance, that, under Caesar, Quintus Valerius Orca carried out this task as legatus pro praetore.”

This information comes from two letters (‘Letters to Familiars’, 13:4-5) that Cicero wrote in 45-4 BC to his friend Orca, whom he addressed as legatus pro praetore and who was engaged in settling Caesar’s veterans at the Etruscan city of Volaterrae. Cicero interceded on behalf of (respectively): the city itself; and Gaius Curtius of Volaterrae, whom Caesar had just appointed to the Senate. Having made his case on moral and legal grounds, Cicero pointed out to Orca that:

-

“There is one thing about which you can have no hesitation: you would [be glad] to have a town of such sound and well-established credit and of so honourable a character for ever bound to you by a service of the highest utility on your part” (‘Letters to Familiars’, 13:4).

This combination of arguments and inducements seems to have been successful: as Nicola Terrenato (referenced below. at p. 108) pointed out, the archeological and epigraphical evidence suggests that:

-

“... Cicero's lobbying had a remarkably positive effect for the whole community, not only maintaining the estates and reinforcing the social position of his aristocratic clients but also allowing small farmers, who probably knew very little of what was happening at the world-scale, to go about their everyday life pretty much undisturbed.”

Ronald Syme (referenced below, at p. 68) suggested that, in view of the fact that Resius subsequently held the same title as Orca:

-

“The man from Mevania may have earned the gratitude of his fellow citizens for things done (or not done) when a land commissioner in the period between Caesar and Caesar Augustus [i.e. 44-27 BC]”.

If so, then these services were most probably rendered in the context of the veteran settlement in the Valle Umbra at around the time of the Perusine War.

I would like to suggest that Mevania had, in fact, been selected for colonisation, but that Resius was persuaded (or managed to persuade his superiors) to settle for:

-

✴the vicus at Hispellum, which would provide a good site for the urban centre of the new colony and was also close to tracts of good agricultural land that could be confiscated from Asisium;

-

✴the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia; and

-

✴for good measure, the sanctuary at the Fonti del Clitunno.

This would be sufficient for a prosperous colony that could, in addition, be placed at the heart of the religious life of the Valle Umbra.

Sanctuaries Confiscated from Mevania

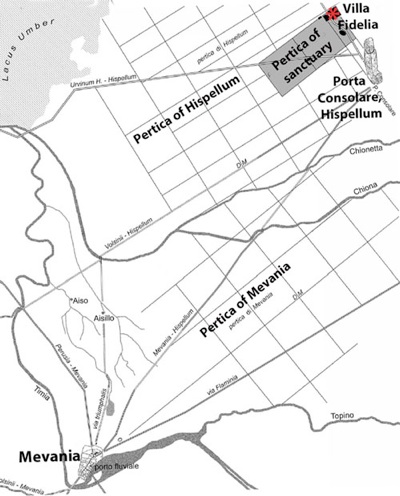

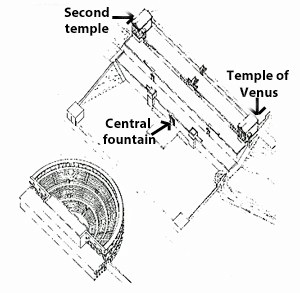

Locus sacer at Villa Fidelia

Adapted from Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, Figure 13)

See also, for example, Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, 2012, Figure 16)

Villa Fidelia

As discussed in my page on the Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia before 41 BC, the evidence for the change in the ownership of the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia at the time of the colonisation of Hispellum first emerged in a study of the centuriation of this part of the Valle Umbra by Manconi, Camerieri and Cruciani (referenced below, at pp. 406-9): their study revealed that the it stood on the northeastern fringe of a rectangular ‘island’ of land (illustrated above) that was:

-

✴not aligned with the centuriation of the land immediately surrounding it, which had been established for the new colony at Hispellum in 41 BC; but rather

-

✴aligned with the older centuriation of Mevania.

This rectangle extended to the southwest beyond the area that was monumentalised in the Augustan period (see below), as far as the church of Santa Maria del Mausoleo. Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 430) pointed out that:

-

“... the new land division [at Hispellum] ... had evidently preserved and surrounded the undivided land that had previously been assigned to the ancient sanctuary. This enclave thus maintained its quality as a locus sacer [sacred place], along with its original orientation, which had been established in a previous programme of centuriation ... “ (my translation).

Sisani (as above) then drew the following conclusion:

-

“The coherence between [the orientation of the land belonging to] the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia and the centuriation of Mevania obviously indicates that:

-

-the sanctuary had originally belonged to Mevania; and

-

-it was transferred to Hispellum ... only at the moment when the colony was formed” (my translation).

Whatever the earlier status of the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia, we can say with some confidence that, by transferring both this sanctuary and the sanctuary at the Fonti del Clitunno to Hispellum, he transformed Hispellum into the major city of the Valle Umbra. The impressive monumentalisation of the site at Villa Fidelia, probably in ca. 27 BC, would have further enhanced its position by providing facilities that were large enough to accommodated pan-municipal religious festivals (as discussed further below).

Laghetto dell’ Aisillo

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 430) suggested that Mevania suffered the confiscation of another sanctuary at this time, one that was located at the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo, some 2.5 km north of the city:

-

“Not by coincidence, the same dynamic [that related to the confiscation of the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia] is also traceable in relation to the sanctuary at Aisillo, which was also monumentalised at the end of the first century BC; [its surrounding centuriation was aligned] not with the pertica of Mevania but with that of the colony of Hispellum: following the deduction [of Hispellum], the sanctuary and its surrounding land (including the nearby Lake Aiso) were ... incorporated within its territory, which projected westward almost as far as the course of Timia, as evidenced by the traces (quite unstable but nevertheless significant) left by centuriation” (my translation).

Sisani expanded this point (at p. 433, note 130):

-

“The northern fringe of the ancient territory of Mevania ... was directly incorporated within the pertica of Hispellum [at the time of its colonisation], ... including [inter alia] the sanctuary of the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo. The presence of colonists from Hispellum in this area is documented with certainty by at least one inscription (AE 1989 282) ... ” (my translation).

This funerary inscription, which is from an unknown location in Bevagna, is now at 27 Via Alcide de Gasperi, just north of city, outside Porta Cannara. It apparently dates to the 1st century AD and commemorates the anonymous:

..... / [H]ispell(atium) / servo

It seems to me that the evidence for the centuriation in an area like this, which has been subject to extensive human intervention over the centuries in the interests of river management, make it difficult to be sure of the extent of confiscations here. While Sisani’s hypothesis is suggestive, his assertion that the evidence is “quite unstable but nevertheless significant” perhaps overstates the case.

Land Confiscations at Mevania ?

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, p. 433) deduced that the land assigned to the new colony at Hispellum:

-

“... almost tripled its territory, at the expense, in the first instance, of Assisi ..., but also of Spoleto, Mevania, Vettona, Arna and, outside the Valle Umbra, Perusia and Tifernum Tiberinum” (my translation).

The evidence for this land confiscation is largely epigraphic: Hispellum was the only centre in the Valle Umbra that was assigned to the Lemonia tribe. If (as I argued above) Hispellum was assigned to the Lemonia only at the time of its colonisation, then inscriptions in locations that once belonged to other centres point to the clear possibility that the locations in question had been confiscated at the time of colonisation.

Such evidence in the case of Mevania might be found in four inscriptions (CIL XI: 4907, 5118, 5275 and 5286) that Enrico Zuddas and Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, pp. 61-2) considered constituted:

-

“A ... group ... from the area around Mevania, which ... [suggest that the city was] surrounded by ‘hotspots’ of the Lemonia” (my translation).

S

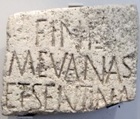

imone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 433, note 130) argued that the last three of these inscriptions:

-

“... could relate to either Hispellum or Sentinum [both of which belonged to the Lemonia]: the latter municipium had extra-territorial possessions in the territory of Mevania, as evidenced by a cippus [from an unknown location in Bevagna, now in the Museo Civico there] that carries the inscription (CIL XI 5039):

-

Finis/ Mevanas/ et Sentina(s)

-

... I have been able to inspect the inscription, the paleography of which suggests a dating of the middle of the 1st century BC” (my translation).

However, it is not absolutely clear that ‘Sentina(s)’ did actually relate to Sentinum. If it did, then it seems to me that, since, according to Cassius Dio, (‘Roman History’, 48: 13: 2-4), Sentinum had revolted against Octavian in 41 BC, any enclaves of land that it retained intil then in the Valle Umbra would have been confiscated in the aftermath of Octavian’s victory at Perusia. I therefore think that the men from the Lemonia tribe recorded three inscriptions considered in this context by Sisiani (CIL XI: 5118, 5275 and 5286) probably all belonged to Hispellum.

CIL XI 5118

This now-lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5118) from Gualdo Cattaneo, some 10 km southwest of Bevagna, read:

Dis manibus/ L. Praecilius L. f. Lem(onia)/ Severus natus Mevaniae

Praeciliae matri kariss(imae) f(ecit)

Enrico Zuddas and Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, pp. 61-2) observed that:

-

“Although the inscription is lost, the comparison of the names of the mother and her (natural?) son ... takes us back to the early imperial age” (my translation).

The EAGLE database (see the CIL link) dates it more specifically to the Augustan period (27BC - 14AD).

It seems that, although Praecilius had been born in Mevania, he was domiciled at Hispellum (as evidenced by his tribal assignation). By way of comparison, Zuddas and Spadoni drew attention to a veteran of legio XXXXI Augusti Caesaris, who was commemorated in a funerary inscription (CIL XI 4654) from San Valentino, south of Todi [where is it now?], which reads:

C(aius) Edusius Sex(ti) f. Clu(stumina)/ natus Mevaniae

centurio legion(is) XXXXI/ Augusti Caesaris/ et centurio classicus

ex testamento

The veteran Edusius, who had also been born in Mevania, had apparently received land at the new colony of Tuder (Todi), which had probably been established in ca. 36 BC. Both Edusius and Praecilius would originally have been assigned to the Aemilia tribe (the tribe of Mevania), but it seems that each of them had subsequently adopted the tribe of the colony in which he had settled: Edusius thus belonged to the Clustumina of Todi; and Praecilius to the Lemonia of Hispellum.

It is, of course, possible that the land at Gualdo Cattaneo on which Praecilius buried his mother had been in his family for some time, and that the land that Praecilius himself owned was closer to Hispellum. However, it is alternatively possible that the land at Gualdo Cattaneo had been confiscated from Mevania for the benefit of the new colony, and that Praecilius (or perhaps his father) had been among the veterans who were settled there.

CIL XI 5275

This funerary inscription (

CIL XI 5275) was found in 1836 near Fiamenga (midway between Bevagna and Foligno) and

is now in the Museo Archeologico at Palazzo Trinci, Foligno. It commemorates:

Cn(aeus) Decimius Cn(aei) f(ilius) Lem(onia) Bibulus

evocatus leg(ionis) XIII/ VIvir

Thus, Cnaeus Decimius Bibulus had been:

-

✴an evocatus (a soldier who had served out his time and obtained a discharge but had voluntarily enlisted again, usually in his old legion) of Legio XIII; and

-

✴a Sevir, a member of a college of six that was probably similar, at least in some respects, to the Seviri Augustales.

The EAGLE database (see the CIL link) dates it to the Augustan period (27BC - 14AD). For reasons discussed below, I think that Bibulus had probably obtained his second discharge after Actium (31 BC) and that he was part of a putative second wave of veteran settlement at Hispellum (one that did not involve further land confiscations).

Lawrence Keppie (as above) regarded the find spot of Bibulus’ tombstone as:

-

“... the southern limit of the ager Spellas ...”;

and Enrico Zuddas and Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, at p. 62), following Ferdinando Castagnoli, suggested that it was at:

-

“... the point of convergence between the territories of Spello, Bevagna and Foligno” (my translation).

Thus it is not clear whether the land for the enclave had been confiscated from Mevania or from Fulginae (Foligno). However, since these seems to have been a colonial enclave at the nearby Gragnano that had probably belonged to Foligno, it seems to me that Foligno is also the more likely candidate as the original owner of the land at Fiamenga. Fiamenga was probably on Via Flaminia, and the remains of two Roman tombs survive along the SS 316 here, which probably follows the line of the Roman road. I wonder whether the putative enclave of Hispellum here was used for burial purposes and/or secured a degree of control over Via Flaminia.

CIL XI 5286

This now-lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5286) from Fiaggia, some 5 km northwest of Bevagna reads:

Statius T. f./ Lem(onia) sevir

The EAGLE database (see the CIL link above) dates to the period 20BC - 20AD.

This family is also attested at Spello itself:

-

✴An inscription

(AE 1948, 0102, illustrated here), which was found near

Porta Venere and which is now in Palazzo Bianconi, records a public project undertaken by the

duoviri (the principalmagistrates of the colony) with the consent of the

ordo decurionum (Council). The

duoviri are named as:

-

•Quintus Statius, son of Publius; and

-

•Publius Safena, son of Titus.

-

The EAGLE database (see the AE link above) dates it to the period 30BC - 14AD.

-

✴A now-lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5340) from an unknown location in Spello commemorated the freedman Marcus Statius Chilo. [Date ??]

Thus it seems that there was an enclave of the new colony around Fiaggia and that the settlers included members of the apparently prominent gens Statia.

CIL XI 4907

This now-lost funerary inscription [date ??] from Castel Ritaldi (some 15 km south of Bevagna and 19 km north of Spoleto) read:

...Pomponius T f./ Lem(onia) Ruf(us) ...

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 433, note 129) suggested that it constituted evidence of land confiscation for veteran settlement in the area. The find spot was on the border of Mevania and Spoletium, so it is not clear which forfeited land for this purpose. However, as Sisani pointed out, other nearby confiscations had been carried out at the expense of Spoletium, comprising the sanctuary at the Fonti del Clitunno and adjoining land that was apparently centuriated for settlement of veterans of Hipellume. We might reasonably assume that this was also the case for the confiscated land evidenced by CIL XI 4907.

Conclusions

Of the four inscriptions recording men from the Lemonia in sites around Mevania, only one (CIL XI 5286, from Fiaggia) relates to veteran settlement on land that had (or probably had) belonged to Mevania:

-

✴CIL XI 5118 (from Gualdo Cattaneo) might have been on land that the family of Praecilius had owned at Mevania since before colonisation;

-

✴CIL XI 5275 (from Fiamenga) might have been on land that had originally belonged to Fulginae; and

-

✴CIL XI 4907 (from Castel Ritaldi) might have been on land that had originally belonged to Spoletium.

Furthermore, none of these inscriptions can be securely linked to the initial phase of colonisation, which would have involved land confiscations. Indeed, in at least one case (CIL XI 5275, which marked the burial of the evocatus Cnaeus Decimius Bibulus at Fiamenga), the land had probably been acquired in a second wave of colonisation after Actium when (as I discuss below) the land in question would more probably have been purchased. In short, while Mevania might have suffered land confiscations in ca, 40 BC, the surviving evidence does not demonstrate that any such losses occurred on a substantial scale. Perhaps this is another example of the good work of Mevania’s patron, Titus Resius (above).

Mevania after the Victory at Actium (31 BC)

The people of the Valle Umbra had seen the worst in the young triumvir Octavian in 41-40 BC, at the time of the Perusine war and the deduction of the colony of Hispellum. As Laurence Keppie (referenced below, at p. 61) observed:

-

“The method of acquiring land [for veteran settlement at this time] was simple and callous: wholesale confiscation from owners [who were] mostly innocent of any disaffection or disloyalty [to Rome or to the newly-elected triumvirs]. With good reason could the dispossessed complain of the injustice of their plight.”

However, Josiah Osgood (referenced below, at pp. 323-4) analysed the new image that Octavian projected after his victory over Sextus Pompeius at Naulochus in 36 BC, which represented:

-

“... the most significant of several shifts in [his] public image during the triumvirate. ... Now, he would try to ... [repair his image among] the segment of [Italian] society that [he] had antagonised terribly with land confiscations and dissatisfied still further with the war against Sextus ... [He now wanted] to show that there would be an end to chaos, that ... property rights did matter. ... This time, ... there was no need for dispossessed landowners [in Italy] to take up arms. To settle the 20,000 time-served men who had been fighting at least since the battle of Mutina [of 43 BC], Octavian .... used public land ... and some plots abandoned in the colonies of 41 BC, ... [while] other veterans were sent [outside Italy], especially to Gaul, a province in his control.”

Although the Colonia Julia Fida Tuder (at modern Todi, in southern Umbria) was probably established at this time, there is no evidence of further veteran settlement in the Valle Umbria until the period after Octavian’s victory at Actium, when the political climate seems to have been even more benign. Octavian celebrated a triple triumph, for victories in Dalmatia, at Actium, and in Egypt, in 29 BC and accepted the name Augustus two years later. Italy could now look forward to the fruits of his victories in a period of (relative) peace, security and prosperity: the acceptance of what was, in effect, a dictatorship must have seemed a small price to pay.

Octavian now had copious funds with which to embellish his image as the benevolent victor who had brought an end to decades of civil war. Much of this expenditure was devoted to public works at Rome: as he recorded in his biography:

-

“On my own land, I built the temple of Mars Ultor and the Augustan Forum from the spoils of war. On land purchased for the most part from private owners, I built the theatre near the temple of Apollo that was to bear the name of my son-in‑law, Marcus Marcellus. From the spoils of war I consecrated offerings on the Capitol, and in the temples of the divine Julius, of Apollo, of Vesta, and of Mars Ultor, which cost me about 100,000,000 sesterces”, (‘Res Gestae Divi Augusti’, 4:21).

As we shall see below, a similar programme involving the distribution of the spoils of war in order to win hearts and minds extended across Italy, and included the Valle Umbra.

Restoration of Via Flaminia (27 BC)

One of the manifestations of this new political climate must have been the Augustan restoration of the Via Flaminia, one branch of which ran through Mevania. Augustus recorded that:

-

“As consul for the seventh time (i.e. in 27 BC), I constructed the Via Flaminia from [Rome] to Ariminum [modern Rimini, on the Adriatic coast]...”, (‘Res Gestae Divi Augusti’, 4:20).

According to Suetonius, at the same time Augustus:

-

“... assigned the [restoration of the other main Roman] highways to others who had been honoured with triumphs, asking them to use their prize-money in paving them” (‘Life of Augustus’, 30);

We might therefore reasonably assume that Augustus himself used part of his receipts from his triple triumph of 29 BC to finance his restoration of the Via Flaminia. This included the construction of the famous Ponte di Augusto at Narnia (modern Narni), at the start of the western branch that ran through Mevania. Procopius, who wrote in ca. 545 AD, recorded that:

-

“This bridge was built by Caesar Augustus in early times, and is a very noteworthy sight; for its arches are the highest of any known to us” (‘History of the Wars’, 5:17).

According to Cassius Dio:

-

“[Via Flaminia] was finished promptly ... and statues of Augustus were accordingly erected on arches on [the Milvian Bridge, outside Rome] and at Ariminum”, (‘Roman History’, 53:22).

Carsten Hjort Lange (referenced below, at pp. 161-2 and note 46) cited coins that suggest that these were:

-

“ ... ‘triumphal arches’, in as much as they were connected to triumphs, even if their purpose was to honour Augustus for road building. ... [They] operated as triumphal markers in Rome and Italy, glorifying the victory at Actium.”

Frances Hickson (referenced below, at p. 134) observed that:

-

“Both the repair [of Via Flaminia] and the arches [at its ends] were part of a republican tradition by which many triumphatores built or restored public buildings and works in fulfilment of vows and as a means of memorialising their victories.”

It seems likely that the stretches of the restored Via Flaminia in the Valle Umbra were similarly articulated to ensure that the victory at Actium would not be forgotten.

Further Veteran Settlement at Hispellum after Actium ?

As noted above, this funerary inscription (

CIL XI 5275) from Fiamenga (on Via Flaminia, midway between Bevagna and Foligno), which is

now in the Museo Archeologico at Palazzo Trinci, Foligno, commemorates

Cnaeus Decimius Bibulus, an evocatus (a former veteran who had voluntarily re-enlisted)

of Legio XIII. After his second discharge, he had been settled at Hispellum (as evidenced by his assignation to the Lemonia tribe). The EAGLE database (see the CIL link) dates the inscription to the Augustan period (27BC - 14AD).

Lawrence Keppie (referenced below, at p. 179) recorded that Legio XIII had fought with Julius Caesar in Gaul but that it had been disbanded before the Battle of Philippi (43 BC). The legion had been reformed by 36 BC, when (according to Appian, ‘Civil Wars’, 5:87) it saved Octavian’s life after a disastrous battle in his war against Sextus Pompeius. Men who were in service with the legion at that time would not have been discharged until after Actium:

-

✴Lawrence Keppie (referenced below, at p. 179) tentatively suggested that Bibulus could have served at Philippi as an evocatus, even though his old legion had not yet been reformed: if he did so, then he might well have been rewarded with land at Hispellum in 41 BC.

-

✴However, Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 436) suggested that Bibulus had more probably fought as an evocatus in the reformed Legio XIII, in which case he would have been part of a putative second wave of veteran settlement at Hispellum after Actium.

It seems to me that the second hypothesis is more likely, particularly in the light of another funerary inscription (CIL XI 1933) for a veteran from Legio XIII, which was found in 1765 at località Agliano, south of Perugia (now in the deposit of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Perugia). It reads:

C(aio) Allio L(uci) f(ilio)/ Lem(onia)/ centurioni/ leg(ionis) XIII

The EAGLE database (see the CIL link) dates it to the period 30-1 BC. There is nothing to suggest that Allius was an evocatus, so the most likely explanation is that both he and the evocatus Bibulus fought in the reformed Legio XIII and were assigned land at Hispellum (in enclaves some way away from the main centuriated area of the colony) in 31 BC. In the light of the new political climate at this time, we might reasonably assume that the land in these enclaves was purchased rather than confiscated, quite possibly using receipts from Augustus’ triple triumph of 29 BC.

This putative second wave of veteran settlement seems to have been associated with significant urban development at Hispellum. According to Paul Fontaine (referenced below, at p. 258-9):

-

✴Porta Consolare had probably built at the time of the original deduction in ca. 40 BC, as a formal entrance to the originally unwalled colony: while

-

✴the walls (of which long stretches survive) belonged to a second phase.

He observed that:

-

“An attractive hypothesis is that this second phase was executed at the time of Augustus’ restoration of Via Flaminia in 27 BC” (my translation).

Linda Baiolini (referenced below, at p. 90), who accepted Fontaine’s dating of the walls, observed that it was supported by the fact that :

-

“... the Porta Venere is indisputably related, not only to the Porta Palatina at Turin (28 BC), but also with the new typology of gates flanked by towers in a series of monuments in the Cisalpina that are generally (but not unanimously) dated to the early Augustan period” (my translation).

The Porta Venere almost certainly marked the start of a processional road from Hispellum to the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia:

-

✴Manconi, Camerieri and Cruciani (referenced below, at pp. 384-5) suggested that the technique used for the terrace walls of this sanctuary suggest that they were built at broadly the same time as the city walls; and

-

✴Paolo Camerieri and Dorica Manconi (referenced below, at p. 69) suggested that the rebuilding of the Temple of Venus in the sanctuary, which involved the construction of new walls (labelled A in their Figure 1) and a new pronaus, dated to ca. 27 BC, when Augustus had restored Via Flaminia.

In short, it seems that the construction of walls of the colony and the monumentalisation of the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia belong to a major programme of urban renewal that followed the victory at Actium, and that they might well have coincided with a second wave of veteran settlement thereafter.

Augustus, in his biography, recalled that:

-

“In the colonies of my soldiers, as consul for the fifth time [i.e. in 29 BC, at the time of his triple triumph], I gave 1,000 sesterces to each man from the spoils of war; about one 120,000 men in the colonies received this triumphal largesse” (‘Res Gestae Divi Augusti’, 3:15).

He also recorded similar largesse in 30 BC:

-

“To the municipal towns I paid money for the lands which I assigned to soldiers in my own fourth consulship [i.e. in 30 BC] and afterwards in the consulship of Marcus Crassus and Gnaeus Lentulus the augur [i.e. in 14 BC]. The sum which I paid for estates in Italy was about 600,000,000 sesterces, and the amount which I paid for lands in the provinces was about 260,000,000. I was the first and only one to do this of all those who up to my time settled colonies of soldiers in Italy or in the provinces” (‘Res Gestae Divi Augusti’, 3:16).

Laurence Keppie (referenced below) noted (at p. 75) that the small amounts paid to the colonists might have included those that had been settled 41 BC and 36 BC, although this would have been unusual for a triumphale congiarium, which was usually paid only to the veterans who had participated in the victory for which the triumph was awarded. More importantly, he suggested (at p. 76) that most of the 600,000,000 sesterces that he paid for land for veteran settlement in Italy would have been paid in 30 BC. I would like to make two suggestions:

-

✴The more obvious one is that the Valle Umbra would have benefitted significantly from these distributions, as well as from Augustus’ expenditure of part of the fruits of his triumphs on the restoration of the Via Flaminia (above). They local people, no less than the veterans settled here in 41 BC and 30 BC, would probably to share (or, at least to manifest) the triumphal euphoria that was then in vogue.

-

✴It is noteworthy that the two veterans from Legio XIII who had probably been among the settlers of 30 BC had been buried in what seem to have been enclaves of Hispellum that were remote from its urban centre. I wonder whether most or all of these enclaves (in the Valle Umbra and further afield (at Perugia, Arna, Bettona and Città di Castello) were acquired by land purchases in 30 BC rather than in the confiscations of a decade before.

Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia

Reconstruction of part of the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia in the imperial period

From Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, 2010, Figure 15)

With kind permission of the authors

I argue below that Mevania’s association with the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia did not come to an end when it was transferred to Hispellum. To take this further, it will be useful to summarise the history of the sanctuary at this time:

-

✴As discussed in my page on the Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia before 41 BC, there is only scant archeological evidence to illuminate its history before its transfer to Hispellum. Nevertheless, it was of sufficient importance by ca. 40 BC for Octavian to effect this transfer (along with that of the sanctuary of Clitumnus at the Fonti del Clitunno), thereby transforming the ritual landscape of the Valle Umbra.

-

✴The only building on the site of the sanctuary for which there is archeological evidence from before the triumviral period - a probably late Republican temple on the present site of the nunnery of the Suore Francescane Piccolo San Damiano - was restored and dedicated to Venus (as evidenced by the inscription CIL XI 5264) soon after colonisation. As Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at pp. 436-7) pointed out:

-

“[This] represented, above all, the entry into the religious heart of the [Valle Umbra] of the dynastic Caesarian cult of Venus Genetrix, which was central to Octavian’s religious ideology, at least until ... after his victory at Actium ...” (my translation).

-

✴The sanctuary as a whole was monumentalised on a grand scale, probably soon after Actium. As discussed above, the monumentalisation of the sanctuary:

-

•coincided with a larger project for the urban development of Hispellum, epitomised by its new circuit of walls; and

-

•probably coincided with a second wave of settlement there, this time involving veterans who had fought at Actium.

The size of this Augustan sanctuary (and, in particular, of its theatre) strongly suggests that it served both Hispellum and at least some of its neighbouring municipia ,including, presumably, Mevania, the erstwhile owner of the site.

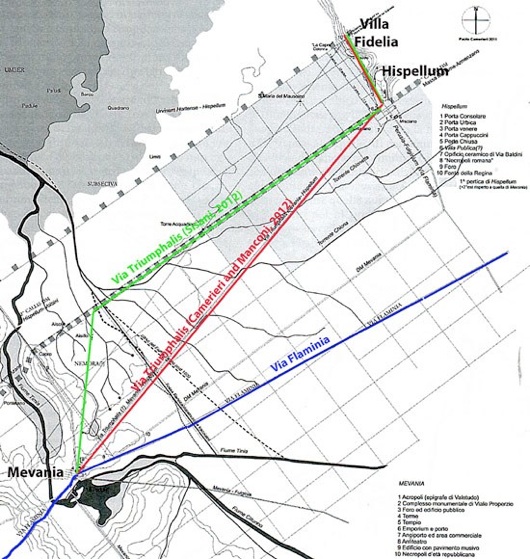

Via Triumphalis

Possible route of the via triumphalis mentioned in CIL XI 5041

Adapted from Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, 2012, Figure 17)

(The route in green is as proposed by Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, Figure 13)

As discussed in my page on Valetudo and the Magistri Valetudinis, the inscription

CIL XI 5041 records that the

Magistri/Novemviri Valetudinis paved a road that was known as the

via triumphalis, using stone from Hispellum. This page also describes its likely route, from the find spot of the inscription (marked on the plan above) to the sanctuary at the Villa Fidelia. The place of the

via triumphalis in the urban development described above is difficult to determine because of uncertainty as to the date of CIL XI 5041:

-

✴If Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 416) is correct that it dates to the “primissima età imperiale”, then this paving of the via triumphalis would have broadly coincided with the monumentalisation of the sanctuary.

-

✴However, if the dating in the EAGLE database (see the CIL link above) to the period 1-30 AD is correct, then we could be dealing with the repaving, in stone from Hispellum, of a road that had been established (and perhaps paved in an inferior material) at the time of the monumentalisation of the sanctuary.

In view of the triumphal character of the restored Via Flaminia (discussed above), it is perhaps unsurprising that the Magistri/Novemviri Valetudinis paved a road called the via triumphalis that (probably) led from Via Flaminia in Mevania to the new pan-municipal sanctuary at Villa Fidelia, a sanctuary that had probably recently welcomed veterans who had fought at Actium, and that would surely witness many celebrations of the victories of Augustus thereafter.

As Frances Hickson pointed out (at p. 137), Augustus never celebrated a formal triumph after his triple triumph of 29 BC, probably because all of the men who had celebrated more than three triumphs in the republican period had been dictators. Nevertheless, as he recorded in his biography:

-

“For successful operations on land and sea, conducted either by myself or by my lieutenants under my auspices, the Senate, on 55 occasions, decreed that thanks should be rendered to the immortal gods. The days on which such thanks were rendered by decree of the Senate numbered 890” ( ‘Res Gestae Divi Augusti’, 1:4).

Augustus was clearly referring to public ceremonies of thanksgiving at Rome, but it seems likely (at least to me) that many of these would have been mirrored in other cities across the Empire, and particularly at Augustan colonies like Hispellum. We learn something about the nature of these ceremonies in the triumviral period (and presumably for some time thereafter) from Cassius Dio:

-

“ ... on the first day of [42 BC, the triumvirs decreed that, inter alia], whenever news came of a [Roman] victory anywhere, ... the honour of a thanksgiving [should be due] to both the victor by himself and to [Julius] Caesar, though dead ...” (‘Roman History’, 47: 18-19).

Perhaps the municipium of Mevania established a processional route from their city to a the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia because this was where thanks would be offered to divus Julius on the occasion of the victories of Octavian/ Augustus. (Indeed, I wonder whether the “second temple” in the plan above, the twin of the temple of Venus, was dedicated to divus Julius).

A Late ‘Marone’

A (now lost) fragmentary inscription (AE 1965, 279a), which was discovered in 1958 on a stone that was embedded near the font of San Bartolomeo, Montefalco, commemorated a man whose name is missing from the top of the stone. The surviving part of the inscription reads:

]Q VI VIR SAC[R?][...

]AEST MARONI I[...

[M]UNICIP(ES) ET INC[OLAE]

This recorded:

-

✴the subject’s tenure in two positions in a municipal magistracy, presumably that of Mevania (Bevagna):

-

•quattuorvir quinquennial (completed from “]Q” in the first line); and

-

•quaestor (completed from “]AEST” in the second line;

-

✴his probable role as a sevir sacris faciundis (completed from “VI VIR SAC[R?][...” in the first line (discussed below); and

-

✴his position as a ‘marone’ (discussed below).

The last line of the inscription presumably referred to the inhabitants of Mevania, including foreign residents (incolae). It is likely that:

-

✴they had dedicated something to the illustrious man named in the dedication; or

-

✴he had undertaken a public commission for their benefit.

Elena Roscini (in L. Agostiniani et al., referenced below, entry 78, pp. 86-7) dated this inscription to the early Augustan period (i.e. to the early part of 27 BC - 14 AD).

The completion of “VI VIR SAC[R?][...” in the first line as sevir sacris faciundis is not completely secure, although this priesthood is known in Mevania from other inscriptions. Laura Bonomi Ponsi (in A. Feruglio et al., referenced below, pp. 85-6; entry 2:121) pointed out that, in this inscription, only the upright of the letter assumed to be “R” survives. The completions could alternatively be ”SACE(rdote)”, in which case the subject would have held the separate posts of sacerdote (priest) and sevir (member of a college of six).

The presence in the cursus of the post of ‘marone’ is unexpected in the period after municipalisation: the word referred to an Umbrian magistracy of two men associated with public works that had been replaced by the aediles after municipalisation. Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 489) pointed out that this had been the case at Mevania (as evidenced for the 2nd century AD by CIL XI 5034). Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2007, at p. 254) proposed that the post of ‘marone’ in AE 1965, 279a represented an:

-

“... antiquarian recuperation, of a cult nature” (my translation).

He amplified this (at p. 289) by suggesting that it was:

-

“... a priestly post, based on the old [magisterial] title from the [pre-municipal] period, recuperated in the context of the revitalisation of the rapport between Mevania and Hispellum, in the context of the paving [by the Magistri Valetudinis] of the processional road known as the via triumphalis [of CIL XI 5041], which led from the old federal capital [Mevania] to the federal sanctuary [at Villa Fidelia]” (my translation).

This hypothesis relies (inter alia) on the assumption that the paving of the via triumphalis constituted the restitution of an ancient processional route (with which the anachronistic ‘marone’ might have been associated in some way). However, as I set out in my page on Valetudo and the Magistri Valetudinis, while possible, this is not necessarily the case. The post of marone here certainly does seem to have been an “antiquarian recuperation” of some kind, but the nature of the post and the reason for its anachronistic name must remain matters for conjecture.

Roman Empire

The city seems soon to have recovered its prosperity, and continued to be celebrated in Rome. Suetonius recorded that, in 39 AD, the Emperor Caligula had:

-

“... gone to Mevania, to visit the river Clitumnus and its nemus (sacred grove)” (‘Life of Caligula’, 43).

Caligula’s sister Agrippina had a villa at Mevania: one of the instances of sudden sex change that Phlegon of Tralles recorded in his “Book of Marvels” took place here in 53 AD:

-

“There was also an hermaphrodite in Mevania, a town in Italy, in the country house of Agrippina Augusta when Dionysodoros was archon in Athens, and Decimus Iunius Silanus Torquatus and Quintus Haterius Antoninus were consuls in Rome”.

It is possible that Caligula had visited Agrippina during his visit in 39 AD, although he exiled her soon after because of her involvement in a plot to murder him.

Writing a few decades later, Pliny the Elder, in an account of varieties of vines, included:

-

“The ‘itriola’, a vine peculiar to Umbria and the territories of Mevania and Picenum”, (‘Natural Histories’, 14:4)

This is perhaps an earlier name for the Sagrantino grape, which is still used in the wines made in the region. At least two writers of this time touched on another aspect of Mevania’s agricultural riches:

-

✴Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella wrote in his treatise on agriculture :

-

“I pass to cattle. Mevania is famous for its herds of tall cattle, Liguria for small” (de Re Rust. 3.8).

-

✴Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (Lucan) wrote of the rumours that had swept through Rome as Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon in 49 BC:

-

“One cries in terror, ‘Swift the squadrons come

-

Where Nar with Tiber joins: and where, in meads

-

By oxen loved, Mevania spreads her walls,

-

Fierce Caesar hurries his barbarian horse.

-

Eagles and standards wave above his head,

-

And broad the march that sweeps across the land’.”

-

‘Pharsalia’ (search on ‘Mevania’)

-

Whether or not this particular rumour was accurate, it is clear that, at the time that Lucan was writing (i.e. ca. 65 AD), Mevania was as renowned as ever for its cattle.

Roman Amphitheatre (1st century AD)

An elliptical depression some 80 meters by 50 meters near Via Flaminia might have been the site of the amphitheatre of Roman Mevania. Excavations here are documented in the reign of Pope Paul III (1534-50), and again in the 19th century, but none of the items discovered then survive. Excavations carried out here in 2006-7 uncovered the remains of walls that apparently support the hypothesis that this was the site of an amphitheatre. Carlo Pietrangeli (referenced below, at pp. 76-9) referred to a three potentially relevant inscriptions:

-

✴a now-lost fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 5061) from an unknown location in Bevagna that reads:

-

[---]us [---]/ [--- amphi?t]heatri [---]/ et eius d[edicatione? ---]

-

which could relate to the dedication of the amphitheatre or of the theatre (below) , and which the EAGLE database (see the CIL link) dates to the 1st century AD;

-

✴a fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 5062) from an unknown location in Bevagna, which is now embedded in the wall of the staircase of the Museo Archeologico, that reads:

-

[ob ho]ṇor[em ---]/ [--- edid]ìt inpen[sa sua]

-

[--- munus g]ladiato[rium ---]

-

which relates to the financing of gladiatorial contests, presumably in the amphitheatre and which the EAGLE database (see the CIL link) dates to the 1st century AD;

-

✴a now-lost fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 5096) from the presumed site of the amphitheatre that reads:

-

[---?] C(aius) Egnatius, C(aius) No[---] / ...

-

which probably originally named two men who had built or restored a public building here, perhaps the amphitheatre itself.

Roman Theatre (1st century AD)

The remains of the arches that formed part of the foundations of the curved part of the semi-circular theatre can be seen from the cellars of the houses that were built above them. The straight façade was parallel to what is now Corso Giacomo Matteotti, which follows the line of the Roman Via Flaminia. As noted above, the inscription CIL XI 5061 could rekate to the dedication of this theatre.

The illustration to the left above is taken from inside a house in Piazzetta del Teatro Romano that is open to the public. That to the right is a hypothetical representation of the original structure, as displayed here.

[1st century AD: river port and warehouse;]

Vespasian (69 - 79 AD)

The people of Mevania must have feared for their continued prosperity, and indeed for their lives in 69 AD when soldiers loyal to Vespasian sacked Bedriacum (Cremona) and marched on Rome. The Emperor Vitellius sent his remaining troops to Mevania to oppose their advance along Via Flaminia. Fortunately for the city, support for Vitellius soon crumbled and he withdrew his remaining forces to Rome. According to Tacitus:

-

“While the occupation of Mevania had terrified Italy and had seemed to start a new war, it was also true that the timid retreat of Vitellius had increased the favourable feeling toward the Flavian party. ... Nevertheless, [Vespasian’s] army had been greatly exhausted by a severe winter storm while crossing the Apennines, and when the troops, though undisturbed by any enemy, found difficulty in struggling through the snow, the leaders realised what risks they would have run, had not that fortune which often served the Flavian commanders quite as much as wisdom turned Vitellius back. In the mountains they met Petilius Cerialis, who had escaped the pickets of Vitellius by disguising himself as a peasant and using his knowledge of the district. Cerialis was closely connected with Vespasian, and being himself not without reputation in war, was made one of the commanders” (‘Histories’, 59.)

The ‘Cerialis’ of this account was Quintus Petillius Cerialis Caesius Rufus, who might have been born in Mevania.

This was certainly the case for another member of the gens Caesia; Sextus Caesius Propertianus. An inscription (CIL XI 5028) on the base of a statue of him, which came from an unknown location in Bevagna (now in the Museo della Città), reads:

SEX(TO) CAESIO SEX(TI) [F(ILIO)] / PROPERTIANO

FLAMINI CERIALI

ROMAE PROC(URATORI) IMP(ERATORIS)

A PATRIM(ONIO) ET HEREDIT(ATIBUS)

ET A LI[B]ELL(IS) TR(IBUNO) MIL(ITUM) LEG(IONIS) IIII

MACEDONIC(AE) PRAEF(ECTO) COH(ORTIS)

III HIS[PA]NOR(UM) HAST(A) PURA

ET CORON(A) AUREA DON(ATO)

IIIIVIR(O) I(URE) D(ICUNDO) IIIIVIR(O) QUINQ(UENNALI) PON(TIFICI)

PATRON(O) MUN(ICIPII)

Thus, as Maria Carla Spadoni (referenced below, 2010, at p. 122) pointed out:

-

“Through the network of adoptions, an exponent of the gens Propertii [of Asisium] ... , Sextus Caesius Propertianus, became a magistrate and patron of Mevania in the Flavian period [as evidenced by CIL XI 5028]” (my translation).

However, François Chausson (referenced below, at p. 118, note 70) noted that:

-

“It is not necessary to believe that the [additional cognomen] Propertianus must indicate an adoption, his mother could have been a Propertia, [in which case, the form of his name] would indicate indicate an alliance between two families belonging to the Umbrian élite” (my translation).

This inscription also records that Sextus Caesius Propertianus held a number of important posts earlier in his career, which included: Flamen Cerialis (a priest assigned to the goddess Ceres); procurator of the private fortune of an emperor; Military Tribune of the Fourth Macedonian Legion; and Prefect of the Third Spanish Cohort. He was also the winner of two high military medals: the Hasta Pura (literally “arrow without a head”); and Corona Aurea (Golden Crown). The Fourth Macedonian Legion was disbanded in 70 AD: Valerie Maxfield (referenced below, at p. 112) suggested that:

-

“[Propertianus’] military service ought to belong to the civil war period, and the decorations to have been awarded by Vitellius - an observation that ties neatly with the fact that no reference is made to the campaign to which the decorations belong nor to the emperor who awarded them.”

Propertianus presumably held his posts of quattuorvir iure dicundo, quattuorvir quìnquennali and pontifex at Mevania thereafter. The EAGLE database (see the CIL link above) dates the inscription to some time during the last three decades of the 1st century AD.

Late Empire

Mevania seems to have continued to prosper thereafter and indeed was further embellished under the Emperor Hadrian (117-38 AD). The temple and the baths that can still be seen near the forum probably belong to this period. So too does the last phase of development of the cult site near Via I Maggio/ Viale Properzio. However, the western branch of Via Flaminia seems to have fallen into relative disuse in the 3rd century AD, and this might have marked the start of the city’s decline.

However, the Clitumnus continued to feature in literature thereafter:

-

✴Claudian described a journey that the Emperor Honorius made from Ravenna to Rome in 404 AD, during which he decided

-

“... to visit Clitumnus' wave, beloved of them that triumph, [because it is from this area that] victors get the white-coated animals for sacrifice at Rome” (‘Panegyric on the Sixth Consulship of the Emperor Honorius’ - search on ‘Clitumnus).

-

✴Claudian (again), in a surviving fragment of a poem about a herd of bulls, favourably compared the herd in question with those raised on the banks of the Clitumnus:

-

“Not such [were] the bulls thou bathest, Clitumnus, in thy stream for pious vows to offer duly to Tarpeian Jove” (‘Description of a Herd’ - search on ‘Clitumnus).

-

✴St Isidore of Seville made two references to it in the 7th century AD:

-

•In a passage in the introduction to his ‘History of the Goths, Vandals, and Suevi’ in which he heaped praise on the fertility of Spain, he included the Clitumnus as a worthy (albeit inferior) comparator for Spanish rivers:

-

“Clitumnus [yields to you] in cattle, ... even though [it] once sacrificed great oxen as victims on the Capitol”.

-

•In “the Etymologies” he noted that:

-

“Lake Clitumnus in Umbria produces very large oxen”

Read more:

E. Zuddas, “Dal Quattuorvirato al Duovirato: gli Esiti del Bellum Perusinum e i Cambiamenti Costituzionali in Area Umbra”, in

S. Evangelisti and C. Ricci (Eds), “Le Forme Municipali in Italia e nelle Province Occidentali tra o Secoli I AC e III DC: Atti della XXIe Rencontre Franco-Italienne sur l’ Épigraphie du Monde Romain (Campobasso, 24-26 settembre 2015)”, (2017) Bari, at pp. 121-32

C.H. Lange, “The Triumph outside the City: Voices of Protest in the Middle Republic”, in:

C.H. Lange and F.J. Vervaet (Eds), “The Roman Republican Triumph: Beyond the Spectacle”, ((2014) Rome, pp. 67-81

P. Camerieri and D. Manconi , “Il ‘Sacello’ di Venere a Spello: dalla Romanizzazione alla Reorganizzazione del Territorio: Spunti di Ricerca ", Rivista di Antichità, 21 (2012) 63-80

S. Sisani, “I Rapporti tra Mevania e Hispellum nel Quadro del Paesaggio Sacro della Valle Umbra”,, in

G. Della Fina (Ed.), “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, (2012) Orvieto (pp. 409-64)

M. C. Spadoni and L. Benedetti, “Perugia Romana 3: La Guerra del 41-40 a.C”, Bollettino della Deputazione di Storia Patria per l'Umbria, 109 (2012) 223-70

M. C. Spadoni, “Perugia Romana 4: L'età di Ottaviano Augusto”, Bollettino della Deputazione di Storia Patria per l'Umbria, 107 (2010) 5-56

L. Agostiniani et al. (Eds), “Screhto Est: Lingua e Scrittura degli Antichi Umbri”, (2011) Città di Castello

P. Cameriere and D. Manconi, “Le Centuriazioni della Valle Umbra da Spoleto a Perugia”, Bollettino di Archeolgic Online, (2010) 15-39

M. C. Spadoni, “Perugia Romana 4: L'età di Ottaviano Augusto”, Bollettino della Deputazione di Storia Patria per l'Umbria, 107 (2010) 5-56

E. Zuddas and M. Spadoni, “La Lemonia nella Valle Umbra”, in

M. Silvestrini (Ed.), “Le Tribù Romane: Atti della XVIe Rencontre sur l’ Épigraphie (Bari 8-10 ottobre 2009”, (2010) Bari

S. Sisani, “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

J. Scheid, “Rome et les Grands Lieux de Culte d’ Italie”, in:

A. Vigourt et al. (Eds), “Pouvoir et Religion dans le Monde Romain: en Hommage à Jean-Pierre Martin”, (2006) Paris, pp. 75-88

J. Scheid, “Augustus and Roman Religion: Continuity, Conservatism, and Innovation”, in:

K. Galinsky ((Ed.), “Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus”, (2005) New York, pp. 175-93

L. Baiolini, “ La Forma Urbana dell' Antica Spello”, in:

L. Quilici and S. Quilici Gigli (Eds), “Città dell' Umbria”, (2002) Rome, pp 61-120

F. Coarelli, "Il Rescritto di Spello e il Santuario ‘Etnico’ degli Umbri”, in:

“Umbria Cristiana: dalla Diffusione del Culto al Culto dei Santi,” Atti del XV Congresso Internazionale di Studi sull’ Alto Medioevo, (2001) Spoleto, pp. 39-52

B. Campbell, “The Writings of the Roman Land Surveyors: Introduction, Text, Translation and Commentary”, (2000) London

N. Terrenato, “Tam Firmum Municipium: The Romanization of Volaterrae and Its Cultural Implications”, Journal of Roman Studies, 88 (1998) 94-114

D. Manconi, P. Camerieri and V. Cruciani, “Hispellum: Pianificazione Urbana e Territoriale”, in:

G. Bonamente and F. Coarelli (Eds),“Assisi e gli Umbri nell' Antichità” Assisi (1996) pp. 375-423; the section on the sanctuary is at pp. 381-92

A. Feruglio et al. (Eds), “Mevania: Da Centro Umbro a Municipio Romano”, (1991) Perugia

P. Fontaine, “Cités et Enceintes de l'Ombrie Antique” (1990) Brussels

F. Chausson, “Note sur Trois Clodii Sénatoriaux de la Seconde Moitié du IIIe Siècle”, Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz, 9:1 (1998) 177-213

E. Gabba, “Trasformazioni Politiche e Socio-Economiche dell' Umbria dopo il 'Bellum Perusinum'”, in:

G. Catanzaro and F. Santucci (Eds), “Bimillenario della Morte di Properzio”, (1986) Assisi, pp. 95-104

J. B. Solodow, “Raucae, tua cura, palumbes: Study of a Poetic Word Order”, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, 90 (1986) 129-53

L. Keppie, “Colonisation and Veteran Settlement in Italy, 47–14 BC”, (1983) Rome

V. Maxfield, “The Military Decorations of the Roman Army”, (1981)Berkeley and Los Angeles

O. Dilke, “Maps in the Treatises of Roman Land Surveyors”, Geographical Journal

127: 4 (1961) 417-26

R. Syme, “Missing Senators”, Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 4:1 (1955) 52-71

Ancient History: Pre-Roman Mevania Fonti del Clitunno

Mevania after the Conquest Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia before 41 BC Other Sanctuaries

Mevania after the Perusine War Valetudo and the Magistri Valetudinis

Return to the page on History of Bevagna.