Valetudo

CIL XI 5059

A large number of inscriptions from Bevagna relate to a magistracy known as the magistri or novemviri Valetudinis (discussed below), a title that is not known anywhere else. This magistracy was presumably associated with the goddess Valetudo, although there is only one surviving record from Bevagna that (probably) refers directly to her: this inscription (CIL XI 5059, 2nd century AD), which is on a fragment of a marble plaque that was found in an unknown location in Bevagna in 1781, and which is now in the Museo Archeologico, reads:

“VALETUDINI [...]/ MAGISTER [...]”

According to Giuseppina Prosperi Valenti (referenced below, 2005, at p. 42), it was part of a dedication to the goddess (whose name is given in the dative) by a now-anonymous magister, presumably a magister Valetudinis.

Origins of Valetudo

RRC 442/1: SALVTIS/ MN·ACILIVS III·VIR·VALETV

Evidence

Valetudo was associated with Salus (the goddess of welfare) on a silver denarius (RRC 442/1) that was minted by Manius Acilius Glabrio at Rome in 49 BC. This coin has:

-

✴a bust of Salus on the obverse; and

-

✴a figure of Valetudo leaning on a column and holding a sacred snake on the reverse.

The snake identifies Valetudo with the Greek goddess Hygeia, the daughter of Aesculapius: while Aesculapius was associated with healing, Hygeia was associated more specifically with the prevention of sickness and the continuation of good health (and her name is the source of the word ‘hygiene’). As Anna Clark (referenced below, at p. 153) pointed out, Acilius Glabrio had probably featured her on this coin because (as Pliny the Elder later recorded in the ‘Natural History’, 29:6) Archagathus, the first Greek doctor to practice in Rome, had done so “in compito Acilio” (at the crossroads of the gens Acilii): Manius Acilius Glabrio was probably claiming credit here for the fact that his family had introduced Greek expertise in the art of healing to Rome.

The most extensive epigraphic evidence for Valetudo is in the inscriptions from Bevagna that relate to the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis, which date to the period between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century AD (as discussed below). However, as Cesare Letta (referenced below, at p. 332) pointed out, earlier evidence for the goddess existed in two now-lost inscriptions from what is now Lecce dei Marsi on the Fucine Lake, in the Abruzzo:

-

✴An inscription (CIL IX 0390, 2nd century BC) recorded a dedication to the goddess by an individual:

-

V(ibius) Vetius Sa(lvi) f(ilius)/ Valetud(i)n[e?]

-

d(onum) d(at) l(ibens) m(erito)

-

✴A second inscription (CIL IX 3813, early 1st century BC) recorded another dedication to her, this time made by the people of vicus Annius:

-

Aninus vecus/ Valetud(i)n[e?]/ donum/ dant

Another possibly relevant inscription (AE 1988, 0465) came from nearby Alba Fucens, a Roman colony that had been established in 309 BC:

T(itus) Avid[ius, son of ?]/ IIIIvir i(ure) [d(icundo)]/ Valetud ...

Edward Bispham (referenced below, at p. 491) dated this inscription to the triumviral or Augustan period. Both Bispham (at p. 315) and Cesare Letta (at p. 333) completed “Valetud ...” as “Valetudini”, which indicates a dedication to Valetudo, preferring this to the alternative, “valetudinarium” (military hospital).

A much later inscription (AE 1987, 0361, ca. 100 AD) from Monte Cimino (at what is now Arcella, some 10 km south of Viterbo) reads:

Bonae Valetudini sacr(um)/ Cn(aeus) Pacilius Marna

sev(i)r/ Sutrio Aug(ustalis) Faleris ex voto

Pacilia Primitiva bon(a)e Bonad/iae Castre(n)si ex voto sacrum

According to André Chastagnol et al. (referenced below, at p. 101, entry 361):

-

“Cneus Pacilius Marna, who was a sevir of the nearby city of Sutrium and an Augustalis at Falerii Nova, acquitted a vow to Bona Valetudo. Pacilia Primitiva, for her part, acquitted a vow to [Bona Dea] Castrensis. There was a water sanctuary here, where the two goddesses, who very close to each other, were venerated. The epithet ‘Castrensis’ that was applied to Bona Dea was used, without doubt, because the goddess had a sanctuary in the ‘castra fontanorum’ on the Esquiline at Rome (evidenced by CIL VI 0070, of the Julio-Claudian period)” (my translation).

(There is an photograph of the inscription in the webpage of the Province of Viterbo).

Pre Roman Origin ?

Cesare Letta (referenced below, at p. 336) argued that Valetudo never had an autonomous cult at Rome:

-

“Hygeia, who was welcomed [to Rome] with Aesculapius in 293 BC [with a temple on the Tiber Island], assumed in Rome only the name Salus ...” (my translation).

He suggested (at p. 338) that this:

-

“... gives considerable support to the hypothesis that we are dealing with a cult that was originally Italic. Its Latin name does not present difficulties [for this hypothesis] ... the Latin root valeo ... was certainly present in the Osco-Umbrian dialects ... It is therefore unsurprising that, once Latin began to be employed in religious inscriptions, the followers of the goddess used a Latin word for her that corresponded to her Italic name: we are not dealing with an ‘interpretation’ so much as with the direct continuation of the name by means of a simple adaptation to Latin form” (my translation).

Other scholars support Letta’s opinion that Valetudo was of Italic origin:

-

✴Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 497) referred to:

-

“Valetudo, whose cult in Umbria was certainly the fruit of a Roman interpretation of a local divinity ...” (my translation).

-

✴Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, at p. 48) asserted that Valetudo was:

-

“... probably a Roman interpretation of an Umbrian deity of virtus (bravery and military strength) as well as sanatio (healing) ...” (my translation).

Roman Origin ?

Giuseppina Prosperi Valenti (referenced below, 1998, at pp. 51-60) argued that, on the contrary, an autonomous cult of Valetudo existed in Rome, as evidenced, for example, by the fact that Nigidius Figulus (who was probably writing shortly before the minting of the coin above) included her in his ‘De Diis’ (About the gods). This opinion has received support in recent scholarship:

-

✴Anna Clark (referenced below, at p. 159 and note 106), who considered the opinions of Letta, Prosperi Valenti and others, concluded:

-

“Although it is impossible to assert conclusively that Valetudo had a cult location in Rome itself, it appears very likely that both [Salus and Valetudo on the coin mentioned above] were intended to be recognised as divine qualities, and that they were [indeed] so recognised [in Rome].”

-

✴Tesse Stek (referenced below, at p. 163), in an account of the inscription (CIL IX 3813) from the vicus Annius (above), concluded:

-

“Valetudo, to whom the vicus Aninus dedicated a sanctuary, has been regarded as a typical ‘Italic’ goddess by [Cesare] Letta . It seems, however, more logical to link her to Roman ideologies in this period. Indeed, Giuseppina Prosperi Valenti has argued – independently from the vicus discussion – that Valetudo should be understood as a typical Roman goddess, in the vein of ‘divine virtues’ or ‘qualities’ of 3rd century Rome.”

-

✴Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, at pp. 88-9) argued that:

-

“... Valetudo was famously embedded in [Roman] legionary camps, within which she was venerated, not primarily in her aspect as a goddess of general well-being but, more specifically, to ensure the achievement and maintenance of that optimal state of both psychological and physical well-being among the soldiers that was indispensable for the achievement of victory. In effect, only this prominently [Roman] military character of Valetudo could justify the involvement of a magistracy from Mevania that was dedicated to her [in the paving of] a road ... that evoked triumphs” (my translation).

Two inscriptions discussed by Tesse Stek (referenced below, at p. 158) record the presence of the goddess Victoria at the vicus Supinum, which was (like the vicus Annius, above) on the Fucine Lake:

-

✴the older inscription (CIL IX 3849), which Stek assigned to the 3rd or early 2nd century BC, read:

-

vecos Sup(i)n[a(s)/ Victorie seino(m)/ dono dedet/ lub(en)s mereto

-

queistores /Sa(lvius) Magio(s) St(ati) f(ilius) / Pac(ios) Anaiedio(s) St(ati) [f(ilius)

-

✴the other inscription (CIL IX 3848), which Stek assigned to the second half of the 2nd century BC, read:

-

Sa(lvius) Sta(tius) Fl(avi)/ Vic(toriae) d(onum) d(ant) l(ibentes) / m(erito)

There is no doubt that Victoria, the goddess of victory, had a cult in Rome: Lucius Postumius Megellus built at a temple to her on the Palatine in 294 BC. Stek concluded (at p. 164) that:

-

“... the appearance of Victoria [at vicus Supinum] should be primarily seen in the context of the new ‘divine virtues’ thriving in Rome at that time. In other words, just as Valetudo (‘Health’) was venerated by the vicus Aninus, the Roman value of ‘Victory’ was venerated as a deity in the [nearby] vicus Supinum.”

Conclusion

It seems to me that, in the absence of any hard evidence for an Italic precursor of Valetudo, and indeed any evidence before the 2nd century BC for her presence in Italy outside Rome, we must assume that she was first introduced at Rome, perhaps initially as a divine quality. I put forward further (admittedly circumstantial) evidence for this hypothesis in the section “Similar Magistracies at Aquinum/ Casinum and Patavium ?” below, in which I argue that the magistracies of:

-

✴the Concordiali at Patavium;

-

✴the seviri Victoriae of Aquinum/ Casinum; and

-

✴the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis of Mevania;

were probably all associated with Roman cults of divine qualities (respectively Concordia, Victoria and Valetudo).

Valetudo and Victory

RIC I Augustus 369: C·ANTISTI·VETVS·III·VIR/ PRO VALETVDINE CAESARIS S P Q R

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, p. 497) asserted that:

-

“Valetudo, whose cult in Umbria ... seems to have been of particular importance, was complex, linked not only to the sphere of salus but also to that of victoria” (my translation).

This hypothesis, together with Sisani’s view (above) that Valetudo had ancient Italic origins, was fundamental to his analysis of the significance of the via triumphalis that the magistri Valetudinis of Mevania paved in the Augustan period (discussed below): Sisani assumed that the via triumphalis must have followed the route of an ancient Umbrian triumphal ritual, and that the magistri Valetudinis had ‘adopted’ it because Valetudo was an ancient deity associated with victory and thus with triumphs.

Sisani put forward (at note 76) the following evidence for his hypothesis that Valetudo was associated with victory:

-

✴an aureus (RIC I Augustus 369) minted by Caius Antistitius Vetus in 16 BC that combined a bust of Victory on the obverse with the reverse legend “PRO VALETVDINE CAESARIS S P Q R”, and a reverse motif that depicted a sacrifice made at an altar, presumably for the health of Augustus and at the behest of the Senate and the people of Rome; and

-

✴an account of a prayer used in the Ludi Saeculares of 17 BC (as recorded in CIL VI 32323 and translated into English by Mary Beard et al., referenced below, at pp. 139-44):

-

•Sisani referred to line 95 of the inscription, in which Augustus sacrificed nine lambs to the fates and implored them to grant (inter alia) “incolumitatem sempiternam victoriam valetudinem” (everlasting safety, victory and health) to the Roman people.

-

•This phrase was repeated in line 129, in a prayer that Agrippa dictated to the matrons of Rome after Augustus had sacrificed a cow to Juno Regina: the said matrons then addressed the prayer to Juno on bended knee.

Conclusion

It is clear from the evidence above that the Romans considered victory and health to be related gifts that could be sought from the gods. (Indeed, Paolo Camerieri, in the reference above, pointed out that these evocations of 17 BC demonstrated that Valetudo was established at Rome before she was documented at Mevania). However, it is less clear (at least to me) that this evidence demonstrates that the cult of Valetudo was directly linked to the sphere of victory. Harold Mattingly (referenced below, at p. 13) gave an explanation of the iconography of the coin that did not require this link:

-

“The health of Augustus was notoriously weak and, in 23 BC, he underwent a severe illness that almost cost him his life. No special crisis in his health is recorded for 16 BC but, as he was about to leave Rome for Gaul [at this point], ... his continuance in well-being was a matter of more than ordinary importance.”

The legend “PRO VALETVDINE CAESARIS” the coin above certainly suggests that Valetudo was associated with the health of Augustus, which was a prerequisite for his future victories (in Gaul and elsewhere). However, pace Sisani, I do not think that either the coin or the prayer at the the Ludi Saeculares demonstrates that Valetudo was considered to be a bringer of victory in her own right.

Valetudo at Mevania

Two finds from Mevania provide circumstantial evidence for the veneration here of Aesculapius and Hygeia, and hence for the presence of a cult of healing:

-

✴an inscription (CIL XI 5025, date ??) on an altar (now lost) that was once in the garden of the former convent of San Paolo dei Cappuccini, which read:

-

“(H)ygiae sacrum”; and

-

✴the statue of Aesculapius (date??) illustrated here, which was found in a Roman domus in Bevagna in the 18th century. (This statue was taken to Rome in 1812 and is now in the Sala delle Colombe of Palazzo Nuovo, part of the Musei Capitolini, Rome.)

Unfortunately , I have not been able to date either the inscription or the statue, so it is impossible (at least for me) to say how they relate to the cult of Valetudo in the city.

Cesare Letta (referenced below, at p. 333) suggested that the importance of the magistri Valetudinis at Mevania:

-

“... seems to [represent?] the consecration of a local cult that pre-dated the birth of the municipium [in ca. 90 BC]” (my translation).

He did not give specific reasons for this assertion of a cult of Valetudo at Mevania before municipalisation, although it was presumably related to his opinion (above) that the Latin name Valetudo had been applied to an originally Italic deity here. However, the earliest of the many inscriptions from Bevagna that relate to the magistracy (CIL XI 5046) post-dates municipalisation, perhaps by some decades (as discussed below), and there is no surviving evidence for Valetudo herself at Mevania before this time.

Magistri/ Novemviri Valetudinis

Epigraphic Evidence

Inscriptions Recording Individuals

A number of (mostly funerary) inscriptions from Bevagna and nearby Montefalco record individual magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis. According to Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 426 and note 93), the two earliest of these dated to the period soon after municipalisation in 90 BC:

-

✴A funerary cippus (CIL XI 5046) from an unknown location in Bevagna (now in the Museo Archeologico) commemorates C(aius) Attius C(ai) l(ibertus) Dardanus, magister Valetudinis.

-

✴A travertine funerary stele (AE 1947, 0064) that was found under the convent of San Domenico (now in the Museo Archeologico) commemorates C(aius) Carpelanu[s] C(ai) l(ibertus) Gratus, magister Valetudinis, who was a sagarius (a manufacturer or dealer in woollen cloaks).

However, the EAGLE database (see the CIL links above) dates each of these two inscriptions to a later period:

-

✴CIL XI 5046 is assigned to the last three decades of the 1st century BC; and

-

✴AE 1947, 0064 is assigned to the 1st half of the 1st century AD.

As I discuss below, this significant difference of view is germane to an assessment of the earliest date at which the magistracy could have been established.

Other individual magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis known from inscriptions include the following:

-

✴A fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 5135, 30 1 BC), which is in the convent of San Fortunato, Montefalco, records two novemviri Valetudinis:

-

•Sextus Titellius, son of Caius; and

-

•(?) Trebatius, son of Lucius.

-

✴An unedited inscription (early imperial period ?) from an unknown location in Montefalco, which is now in the Museo Civico there, commemorates C(aius) Aufidiu[s C(ai) l(ibertus)] Agroec[us], magister Valetudinis. (Another inscription (CIL XI 5040) that probably records this individual among his colleagues is discussed below.)

-

✴A travertine (possibly funerary) stele (CIL XI 7927, 1st half of the 1st century AD) from an unknown location in Bevagna (now in the deposit of the Museo Archeologico) commemorates T(itus) Edusius T(iti) l(ibertus) Chrestus, magister Valetudinis, together with a second man whose name is almost lost.

-

✴A now-lost funerary cippus (CIL XI 5048, date ??) from an unknown location in Bevagna commemorated L(ucius) Aulius L(uci) l(ibertus) Optatus, magister Valetudinis.

Three other funerary inscriptions relate to men who were both magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis and seviri sacris faciundis (discussed below):

-

✴A funerary inscription (CIL XI 5044, 1st century AD), which is in the garden of villa Le Contessine (see Walk II), commemorates Statilia Nebris, the wife of the freedman Caius Arruntius Hermes, novemvir Valetudinis and sevir sacris faciundis.

-

✴A now lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5053, 2nd half of the 1st century AD), which was found in an unknown location in Bevagna, commemorated Cnaeus Serius Philetus, magister Valetudinis and sevir sacris faciundis and his wife, Penasia Pallas.

-

✴A funerary inscription (CIL XI 5047, 2nd century AD), which is in the garden of villa Le Contessine (see Walk II), commemorates the freedman C(aius) Attius Ianuarius, novemvir Valetudinis and sevir sacris faciundis, who had left a considerable sum to his guild, the collegio dei centonarii (the guild of manufacturers of patchwork covers known as centones) to finance an annual banquet in his memory for at least 12 men on the festival of the Parentalia. (The collegio dei centonarii erected this funerary cippus: one wonders whether Attius Januarius had also made bequests to the novemvir Valetudinis and sevir sacris faciundis, and whether he consequently received other funerary commemorations.)

Other Inscriptions

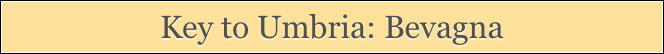

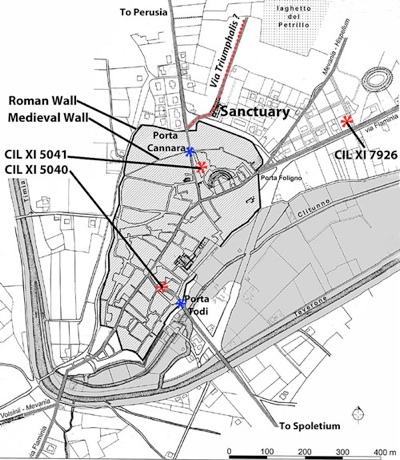

Find spots in Bevagna of CIL XI 7926, 5040 and 5041

Adapted from Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, Figure 2)

Mensa dei Magistri Valetudinis

This large marble altar table in the Museo Archeologico, which was found in the location marked in the plan above (towards the upper right), contains an inscription (CIL XI 7926, first half of the 2nd century AD) that associates it with the magistri Valetudinis. The surviving part of the inscription is in two parts:

-

✴The inscription on the left edge of the altar table reads:

-

Mag(istri) Valet(udinis): Q(uintus) Aemilius Q(uinti) l(ibertus) Epaphroditus

-

✴The inscription along the front records the names of six other men:

-

•T(itus) Scetanus T(iti) l(ibertus) Dilige(n)s;

-

•C̲(aius) Publienus C(ai) l(ibertus) Pelops;

-

•T(itus) Egnatius T(iti) l(ibertus) Arsaces;

-

•T(itus) Hedusius T(iti) l(ibertus) Arabus;

-

•C(aius) Lisius C(ai) l(ibertus) Cerdo; and

-

•C(aius) Tettiu[s ] ...

The right side of the altar has been lost, but it is almost certain that its edge was inscribed with the names of the two other men who served in the magistracy at the time.

It is possible that the magistri Valetudinis financed the erection of this altar in a public temple in the city, perhaps one dedicated to Valetudo. However, it seems more likely (at least to me) that it came from their meeting place. In this context, Margaret Laird (referenced below, at p. 92 and at p. 74, Figure 31) recorded that the Sacello degli Augustales (the meeting place of the Augustales) at Misenum included a large apsed room that contained an altar, as well as other rooms that were probably used for meetings and banquets of the Augustales: one might envisage a similar meeting place of the the magistri Valetudinis at Mevania. (I wonder whether the magistri Valetudinis sacrificed at this altar at Mevania, perhaps for the health of the emperor).

Via Triumphalis

An important inscription (

CIL XI 5041) in the Museo Archeologico suggests that the

magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis paved a road called the

via triumphalis (triumphal way), as mentioned above. According to Carlo Pietrangeli (referenced below, at pp. 58-9), this inscription was discovered in 1598 under the street (now-stepped) leading to the facade of the church of San Francesco (marked on the plan above):

-

✴Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 416) dated it on paleographic grounds to the “primissima età imperiale” (i.e. to ca. 27 BC); while

-

✴the EAGLE database (see the CIL link above) gives a later date, in the first three decades of the 1st century AD.

Only the lower part of the inscription survives. It records the names of six freedmen:

-

✴[....iu]s [T(iti) l(ibertus) Castus ;

-

✴[T(itus) ...elius] T(iti) l(ibertus) Phileros;

-

✴C(aius) Carpelanus C(ai) l(ibertus) Faustus;

-

✴Sex(tus) Rubrius (mulieris)) l(ibertus) Faustus;

-

✴[...] Lartius [...] l(ibertus) Salvius;

-

✴[...] Cominius [... l(ibertus)] Pylades.

The last three lines read:

-

viam triumphalem / straverunt lapide / Hispellate

The via triumphalis was paved with stone from Hispellum

It seems likely that the missing upper part of the inscription recorded:

-

✴the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis, the magistracy to which all six men almost certainly belonged, which had presumably financed the paving of the road; and

-

✴the names of the three other members of the magistracy at this time.

This project is discussed in more detail in the section “Paving Projects of the Magistri Valetudinis” below.

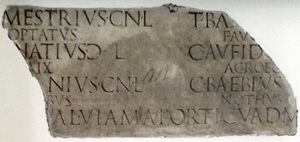

A Second Paving Project

This fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 5040) in the Museo Archeologico relates to another paving project that had been financed by the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis. According to Giuseppina Prosperi Valenti (referenced below, 2005, entry 3), they were found in ca. 1876 behind the church of San Silvestro (marked on the plan above). The surviving fragments records the names of six freedmen in two columns: it seems likely that there were originally three columns and a total of nine names. The surviving names are:

-

✴on the left:

-

•[C]n(aeus) Mestrius Cn(aei) l(ibertus) Optatus;

-

•C(aius) Egnatius C(ai) l(ibertus) Felix;

-

•Cn(aeus) [- - -]anius Cn(aei) l(ibertus) [- - -]bus; and

-

✴on the right:

-

•T(itus) Bae[bius T(iti) l(ibertus)] Faus[tus];

-

•C(aius) Aufidi[us C(ai) l(ibertus)] Agroec[us], who is known from another inscription that is now in the Museo Civico, Montefalco; and

-

•C(aius) Baebius [C(ai) l(ibertus)] Nothus.

Caius Aufidius Agroecus, who is included in the second column, is known from another inscription that is now in the Museo Civico, Montefalco (see above).

The surviving part of the last line of the inscription has been completed as:

[VIIII viri] Val(etudinis) viam a porticu ad m[....... straverunt]

Thus, assuming that this completion is correct, the novemviri Valetudinis had paved a section of a street or road from a portico to a place beginning with ‘m’:

-

✴The original CIL entry, followed by Prosperi Valenti (as above) and by the EAGLE database (see the CIL link), completed m[.......] as m[acellum] (market).

-

✴However, Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, p. 443, entry 2:4) suggested m[iliarium] (milestone).

There is also uncertainty about the date of the inscription:

-

✴Simone Sisani (2012, referenced below, at p. 420) considered it to be broadly contemporary with CIL XI 5041 (above) - i.e. he dated it to ca. 27 BC.

-

✴The EAGLE database (see the CIL link) gives a later date, in the first half of the 1st century AD.

This project is also discussed in more detail in the section “Paving Projects of the Magistri Valetudinis” below.

Range of Dates of the Inscriptions

It will be clear from the above that not all of the 12 inscriptions listed above relating to the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis at Mevania that can be assigned even an approximate date, and that, even where scholars have ventured dates, there is not always agreement.

This divergence of view is particularly important when one tries to establish a terminus ante quem for the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis at Mevania:

-

✴As noted above, according to Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 426 and note 93), the earliest inscriptions recording members of this magistracy dated to the period soon after municipalisation in 90 BC. These were:

-

•CIL XI 5046, which commemorates the freedman Caius Attius Dardanus; and

-

•AE 1947, 0064, , which commemorates the freedman Caius Carpelanus Gratus

-

✴However, in the EAGLE database:

-

•CIL XI 5046 is assigned to the last three decades of the 1st century BC;

-

•CIL XI 5135, which commemorated the free born Sextus Titellius, son of Caius and (?) Trebatius, son of Lucius, is also assigned to this period; and

-

•AE 1947, 0064 is assigned to the 1st half of the 1st century AD.

I make no claim to any expertise in the dating of Latin inscriptions. However, as we shall see below, despite its unique title, the magistracy of the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis at Mevania was apparently the equivalent of the seviri Augustales and similar magistracies that appeared across municipal Italy from ca. 12 BC. Thus:

-

✴If the dates proposed by Sisani are correct, then the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis represented an extremely precocious example of magistracies of this kind.

-

✴However, if the dates assigned in the EAGLE database are broadly correct, then this magistracy was established at Mevania at about the time that similar magistracies were beginning to emerge in other municipia.

It seems to me that the dating proposed in the EAGLE database should be preferred, because it does not require us to assume that sociological developments at Mevania differed markedly from those at other Italian municipalities. Even with this later dating, the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis at Mevania seems to have been among the earliest magistracies of its kind.

The majority of magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis for whom we have names are recorded in inscriptions that probably date to the 1st century AD (although, as noted above, evidence for the dating of some of them is lacking). The magistracy certainly continued into the 2nd century AD:

-

✴the inscription (CIL XI 7926) on the Mensa dei Magistri Valetudinis provides the names of seven magistri Valetudinis in the first half of the 2nd century AD; and

-

✴the inscription (CIL XI 5047), that ecords Caius Attius Ianuarius, novemvir Valetudinis and sevir sacris faciundis, dates to an unknown year of this century.

Historical Context of the Magistracy

According to Henrik Mouritsen (referenced below, at p. 238, note 5):

-

“... the magistri Valetudinis at Mevania appear to be the equivalent of the seviri Augustales [and of similar magistracies in other municipia] ... ”

I discuss his analysis of these magistracies in more detail in my page on Assisi: Quinqueviri and Seviri/ Seviri Augustales at Asisium: the key points are:

-

✴magistracies of this kind were established in almost all of the municipia of Italy from about 12 BC;

-

✴while they were once thought to have been associated with the imperial cult, modern scholarship sees them as secular magistracies;

-

✴unlike other municipal magistracies, membership was not confined to decurions; and

-

✴as a result, their membership was, in most cases, dominated by freedmen.

Henrik Mouritsen (referenced below, at pp. 244-5) summarised:

-

“The posts were honores but, unlike the [other civic] magistracies on which they were modelled, [they] had no civic authority. Theirs were, quite literally, empty honours, which held neither actual power nor ... any defined civic remit or function. ... [We might usefully] focus on the one element that made these honores real - which was their cost ... : the office-holders still had to pay their summa honoraria [entrance fee due to the municipality]. ... These posts therefore represented attempts to widen the pool of public donors ... The new honores ... could be held by anyone, irrespective of birth, provided they had sufficient wealth.”

These magistracies thus provided a route by which men who were excluded from municipal power, often because of their status as freedmen, were nevertheless able to achieve civic prominence, provided that they could afford it.

Although the most common names for these new magistracies were Augustales, seviri Augustales and seviri, Henrik Mouritsen (referenced below, at p. 258) pointed to some 40 other magistracies from this period that had apparently similar characteristics but less common titles. These included:

-

“... a number of bodies with names derived from deities ... the strong similarities [between these bodies and] the seviri and Augustales in terms of membership and functions ... suggest that they belonged to the same broad category of public officials.”

His list of magistracies with titles of this kind comprised:

-

✴magistri Mercuriales and Mercuriales, at a number of Italian municipia;

-

✴magistri Apollinares, seviri Apollinares and Apollinares, also at a number of Italian municipia;

-

✴seviri Victoriae (at Aquinum and possibly at nearby Casinum);

-

✴Concordiali (at Patavium); and

-

✴(as noted above), magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis (at Mevania).

If Mouritsen’s analysis is correct, then the members of the magistracies in this group were not priests of the cults of their titular deities, albeit that it seems likely that they paid particular honours to them.

Mouritsen’s model can be illustrated by comparing the magistri / novemviri Valetudinis of Mevania with (for example) the seviri of nearby Asisium. The latter magistracy was first recorded in an inscription (AE 1989 0290) from an unknown location in Assisi (now in the nunnery of Santa Chiara):

[Ti(berio) Cl]audio Nerone II, Cn(aeo) Calpurnio/ Pisone co(n)s(ulibus)

[Sex(tus) Ve]turius C(ai) f(ilius), VIvir

T(itus) Vìstinius Vìtor, VIvir

C(aius) Quìntius [- - -]us, VIvir

C(aius) [An]tonius Tertius, VIvir

C(aius) Diburnius , [- - - VI]vir

[ ... ]Cn(aei) f(ilius) Sator, [-]

[- - -] straverunt/ ḍ(ecreto) d(ecurionum)

The lower part of the inscription is difficult to read: however, according to Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 366), it:

-

“... records that the seviri [of Asisium] and two other men, perhaps quattuorviri or aediles, financed at their own expense the paving of a road” (my translation).

Because of the current state of the inscription, the sixth sevir and the two other men are now anonymous. The inscription is dated to the consulate of Tiberius and Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso (i.e. 7 BC): according to Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at p. 295):

-

“We are dealing here with the earliest [securely dated] attestations of the title ‘severi’, unqualified by the word ‘Augustales” (my translation).

Thus, we might reasonably assume that the magistracy of the seviri of Asisium was established in or shortly before 7 BC. The inscription reveals that:

-

✴even at this early date, this magistracy at Asisium quite possibly included freedmen, with only Sextus Veturius, son of Caius and Titus Vistinius Vitor securely freeborn; and

-

✴as suggested by the last two lines of the inscription, it engaged in public works (probably, in this case, the paving of a street) under the auspices of the decurions.

The similarities in membership and function between this organisation at Asisium and the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis of Mevania (as evidenced by CIL XI 5040 and 5041, above) are clear: both magistracies were open to freedmen and both engaged in civic projects such as the paving of roads, for which they were duly rewarded by celebratory inscriptions.

In a wider geographical context, Margaret Laird (referenced below, in her Appendix 3) produced a list of municipal projects in Italy involving street-paving and bridge-building that are evidenced by inscriptions. The 15 of these projects that she identified in Regio VI (Umbria) comprised:

-

✴2 (or perhaps 3) that were sponsored by private individuals;

-

✴6 (or perhaps 5) sponsored by civic magistrates;

-

✴5 sponsored by seviri or seviri Augustales; and

-

✴the two at Mevania that were evidenced by CIL XI 5040 and 5041 (above), both of which were sponsored by the magistri Valetudinis (although she did not connect the second of these inscriptions with this magistracy, presumably because the part of the inscription that almost certainly identified the freedmen commemorated as magistri/novemviri Valetudinis has been lost and is unrecorded).

Once more, we see the close similarities between seviri and seviri Augustales on the one hand and the magistri/ novenviri Valetudinis of Mevania on the other, at least in relation to function and commemoration.

Magistracies with Names Derived from Divine Qualities

Mouritsen’s list (above) of magistracies with names derived from deities included two in which the deity in question can be securely characterised as one of the Roman ‘divine qualities’:

-

✴the seviri Victoriae (at Aquinum and possibly at nearby Casinum) were dedicated to Victoria; and

-

✴the Concordiali (at Patavium) were dedicated to Concordia.

Since I argued above that Valetudo also belongs in this category of deities, it is worth considering how these other two magistracies compare with the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis at Mevania.

Seviri Victoriae

This magistracy at Aquinum, in northern Campania (and perhaps at nearby Casinum) is evidenced by two inscriptions:

-

✴a now-lost inscription (CIL X 5416, 1st century BC), which records the paving of the forum at Aquinum, read:

-

L(ucius)] Cofius Eros M(arci) f(ilius)/ seviro Victoriae

-

hic forum Aquini sua/ pecunia stravit

-

[C]ofiae L(uci) l(ibertae) Dion[y]siae / uxoriq(ue) suae

-

✴a funerary inscription (CIL X 5199, date ??]) which is now at the Abbazia di Montecassino (at Roman Casinum, modern Cassino) but which might have come from Aquinum, reads:

-

P(ublius) Lucreti[us ---?]/ sevir Vic[toriae ---?] / Staiae Vìtalì co[niugi ---?]

It seems from the first of these inscriptions that the seviri Victoriae at Aquinum shared characteristics with the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis of Mevania:

-

✴while Lucius Cofius Eros, the son of Marcus, was clearly free born, his Greek cognomen suggests that he was descended from a freedman; and

-

✴his involvement in financing the paving of the forum at Aquinum indicates his prominent role in the civic life of his municipium.

This shared involvement in paving projects is quite distinctive, at least as far as we know from surviving inscriptions: the database complied by Margaret Laird (referenced below, in her Appendix 3) included 137 paving projects in Italy as a whole:

-

✴24 were financed by Augustales, seviri Augustale or seviri; while

-

✴only 3 were financed by other magistrates or magistracies of this kind:

-

•the paving of the forum at Aquinum, financed by the sevir Victoriae Lucius Cofius Eros in the 1st century BC; and

-

•the two road-paving at Mevania, financed by the magistri Valetudinis (evidenced by CIL XI 5040 and 5041) in the late 1st century BC or the first half of the 1st century AD.

This is quite possibly an accident of survival: the 137 surviving inscriptions in the database must represent only a tiny fraction of the original total, which might well have included some that related to other magistracies. However, it does provide some support for the hypothesis that the sevir Victoriae of Aquinum/ Casinum and the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis of Mevania were similar to each other and to the Augustales, seviri Augustale and seviri of other municipia.

Concordiali

As Luciano Lazzaro (referenced below, at p. 187) pointed out, this magistracy seems to have been almost exclusive to the municipium of Patavium (Padua). He published (at p. 188) a list of nine relevant inscriptions from Padua and its surrounding area, all of which dated to the 1st or 2nd century AD. Each recorded a single Concordialis who was, or probably was, a freedman;

-

✴two were also Augustales; and

-

✴a third was also a sevir Augustale.

Unfortunately, these seem to be mainly funerary inscriptions and none of them indicates what functions the Concordiali Patavini undertook by virtue of their office.

Conclusion

I noted above that, in the absence of any hard evidence for an Italic precursor of Valetudo, and indeed any evidence for her presence in Italy (outside Rome) before the 2nd century BC, we should probably assume that she was first introduced at Rome, perhaps initially as a divine quality. It seems to me that, although the evidence added in this section is purely circumstantial, it further supports this hypothesis: in other words, we might reasonably assume that:

-

✴the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis atf Mevania;

-

✴the seviri Victoriae at Aquinum/ Casinum; and

-

✴the Concordiali at Patavium;

were all associated with Roman cults of divine qualities (respectively, those of Valetudo, Victoria and Concordia).

Characteristics of Magistri/ Novemviri Valetudinis

Status

As noted above, freedmen tended to dominate the membership of this type of magistracy. However, as Henrik Mouritsen (referenced below, at p. 247) pointed out:

-

“[They were not] exclusively reserved for freedmen ...: there are many examples of freeborn Augustales and seviri, albeit with great regional and chronological variations. ... [There is also] considerable intra-regional diversity ...: [For example,]:

-

-at Hispellum, seven out of ten severi were explicitly freeborn [as discussed in my page on Seviri and Seviri Augustales at Hispellum];

-

-in sharp contrast to nearby Asisium, where that applied to just three [inscriptions: AE 1989 0290 ; CIL XI 5424; and CIL XI 5426] out of 23 as discussed in my page on Assisi: Quinqueviri and Seviri/ Seviri Augustales at Asisium .”

It seems that the membership of the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis was similar in this respect to that of the seviri/ seviri Augustales of Asisium: 24 of the 28 certain or probable magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis mentioned so far were identified in the inscriptions as liberti (freedmen). In addition:

-

✴Cnaeus Serius Philetus (CIL XI 5053, 2nd half of the 1st century AD), was probably a freedman or descended from one (given the ‘Greek’ nature of his cognomen); and

-

✴C(aius) Tettiu[s ] ... (CIL XI 7926, 1st half of the 2nd century AD) was almost certainly a freedman: the word l(ibertus) was almost certainly given in the now-lost part of the inscription, (given the ‘Greek’ nature of his cognomen)

Only the two novemviri Valetudinis named in the fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 5135, 30 1 BC) from Montefalco were securely free born (as evidenced by their filiation)::

-

✴Sextus Titellius, son of Caius; and

-

✴(?) Trebatius, son of Lucius.

The existence of free born novemvir Valetudinis, as evidenced by CIL XI 5135, might be related to its relatively early date, when membership might have been more heterogenous than it later became.

Family Affiliations

Almost all of the freedmen in these inscriptions followed the usual practice of adding their (usually non-Latin, often Greek) cognomen to the name of the person who had freed them. An interesting example of this is Caius Aufidius Agroecus, who is recorded in two inscriptions (both discussed above):

-

✴an unedited inscription (early imperial period ?) from an unknown location in Montefalco, which is now in the Museo Civico there; and

-

✴among the other members of this magistracy in CIL XI 5040 (1st half of the 1st century AD).

His name indicates that he had been freed by Caius Aufidius, son of Caius. Following normal practice, he would have still belonged to his extended family after manumission. Other members of the gens Aufidia are recorded in surviving inscriptions:

-

✴pe. pe. uferier (Petro Aufidius, son of Petro), the holder of the post of ‘uhter’ (senior magistrate) is recorded in an Umbrian inscription (ST Um 25, 2nd century BC) on the lid of a sarcophagus from Mevania (now in the Museo Archeologico, Gubbio);

-

✴ia.t.ufeřie[r] (Ianto Aufidius, son of Titus), the holder of the post of cvestur farariur (quaestor whose responsibilities were related in some way to the supply of spelt), is recorded in an Umbrian inscription (ST Um 8, ca. 100 BC) on a sundial that was found outside Porta Cannara (now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Perugia); and

-

✴Aufidius Primigenius, who commemorated his servant, [Ci?]arta, in a funerary inscription (CIL XI 7940, 1st half of the 1st century AD) from what was probably a Roman necropolis near Sant’ Agostino (now in the Museo Archeologico, Bevagna).

Clearly the gens Aufidia had been a leading family at Mevania before municipalisation, and had probably survived the Perusine War (41-40 BC) with most of their property, presumably because they had supported (or, at least, not actively opposed) Octavian.

Another six of the 28 known magister/ novemviri Valetudinis belonged to extended families that seem to have been prominent in Mevania in the 1st century BC:

-

✴The gens Rubria included:

-

•Aulus Rubrius (AE 1947, 0063, 1st century BC), a haruspex who was associated in some way with Volsinii;

-

•Rubria, daughter of Titus (CIL XI 7953, 2nd half of the 1st century BC);

-

•a freed man, Caius Rubrius Hilarius Rubella (CIL XI 5068, 1st century AD), who was a ‘negotiator Gallicanus et Asiaticus’; and

-

a magister Valetudinis , the freedman Sextus Rubrius Faustus (CIL XI 5041, ca. 27BC - 30AD), who was the freedman of a lady belonging to this family.

-

✴The gens Tettia included:

-

•a quattuorvir, Quintus Tettius, son of Caius (CIL XI 5055, from the 2nd half of the 1st century BC); and

-

a magister Valetudinis, Caius Tettius( CIL XI 7926, irst half of the 2nd century AD), who was almost certainly a freedman, although (as noted above) the words that probably gave his cognomen and status as a libertus are now lost.

-

✴The gens Edusia included:

-

•Caius Edusius, son of Sextus (CIL XI 4654), who was born in Mevania but who was settled as a veteran of the 24th legion at the colony of Tuder (Todi) in ca. 36 BC; and

-

two freedmen who were magistri Valetudinis: Titus Edusius Chrestus (CIL XI 7927, first half of the 1st century AD; and Titus Hedusius Arabus (CIL XI 7926, first half of the 2nd century AD).

-

✴The gens Attia included:

-

•a quattuorvir, (?) Attius, son of Lucius (CIL XI 5045, from the late 1st century BC); and

-

two freedmen who were magistri / novemviri Valetudinis: Caius Attius Dardanus, magister Valetudinis (CIL XI 5046, 1st century BC); and Caius Attius Ianuarius, novemvir Valetudinis and sevir sacris faciundis (CIL XI 5047, 2nd century AD).

We might reasonably assume that these were families that had:

-

✴supported (or, at least, not opposed) Octavian at the time of the Perusine War; or

-

✴become established at Mevania shortly thereafter.

The evidence presented here suggests that their families provided freedmen who became magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis for a considerable period thereafter.

Paving Projects of the Magistri Valetudinis

Find Spots of CIL XI 7926, 5040 and 5041 in Bevagna

Adapted from Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, Figure 2)

We can now look again at the two paving projects that seem to have been undertaken by the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis (as evidenced by CIL XI 5040 and 5041). Simone Sisani (2012, referenced below, at p. 420) suggested that:

-

“The coincidence between [these projects] - in terms of both chronology and curatorship, which was, significantly, entrusted to a priestly college - can probably be seen as the result of the monumentalisation of a single processional route in the Augustan age ...” (my translation).

He suggested (at p. 428) that this route constituted:

-

“... what was truly a sacred way that passed through Mevania, en route from the sanctuary of Clitumnus [at the source of the eponymous river] to ... that at Villa Fidelia” (my translation).

I have two main reservations about these hypotheses:

-

✴The work of Henrik Mouritsen (discussed above) indicates that the magistri/novemviri Valetudinis were probably not priests, and that there is no particular reason to assume that their public projects were necessarily of religious significance.

-

✴It seems to me that, while the via triumphalis of CIL XI 5041 was probably a processional route, there is nothing to indicate that this was also the case for the unnamed road mentioned in CIL XI 5040.

I therefore discuss the two projects separately.

CIL XI 5040

As discussed above, the inscription CIL XI 5040 records that the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis paved a section of a road from a portico that was presumably inside the city to a place beginning with ‘m’. It was found inside Porta Todi, in a location (marked in the plan above) between this gate and the urban stretch of Via Flaminia:

-

✴Simone Sisani (2012, referenced below, at p. 420) considered it to be broadly contemporary with CIL XI 5041 (below) - i.e. he dated it to ca. 27 BC.

-

✴The EAGLE database (see the CIL link) gives a later date, in the first half of the 1st century AD.

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 443, entry 2:4) completed the ‘m....’ of the inscription as miliarium (milestone), which suggested a partially extra-urban road. He also believed that, since it was paved in part by the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis, it must have had a religious significance. Thus, he suggested (at pp. 419-20) that, proceeding from the find spot, it ran through a gate in the Roman walls near the present Porta Todi, through the grove of Jupiter near Picciche, and on to the sanctuary at the source of the Clitumnus. This sanctuary had probably belonged to Mevania in pre-Roman times: it was transferred:

-

✴to the new colony of Spoletium in 241 BC; and

-

✴to the new colony of Hispellum in 41 BC.

Thus, by the time of the paving project of CIL XI 5040, the sanctuary belonged to Hispellum. (Both the sacred grove and the sanctuary are described in the page on the Fonti del Clitunno).

However, the ‘m....’ of the inscription is more usually completed with m[acellum] (market), which suggests a road within (or largely within) the city walls. This would have been more typical of the projects undertaken by similar magistracies, including, for example, the seviri of Asisium (discussed above). For example, we can reasonably assume that the project that they undertook collectively in 7 BC evidenced by AE 1989 0290 (above):

[- - -] straverunt/ ḍ(ecreto) d(ecurionum)

involved the paving of an urban street: the project had, after all, been decreed by the decurions of the municipium, and the seviri constituted a magistracy that was under their direct control. This was probably also the case in the paving projects at Asisium that were financed by an individual sevir, the freedman Publius Decimius Eros Merula, which are evidenced by two inscriptions that were broadly contemporary with CIL XI 5040:

-

✴The earlier of these (CIL XI 5399) was found during the excavations for the foundations of the church of Sant'Antonio di Padova at Assisi and is now in the Museo Civico there. It reads:

-

P(ublius) Decimius P(ubli) l(ibertus) Eros/ Merula VIvir

-

viam a cisterna/ ad domum L(uci) Muti/ stravit ea pecunia/ ...

-

It records that Merula financed the paving of a section of the street between a cistern and the house of Lucius Mutius. This project is described in terms that are very similar to those used in CIL XI 5040, in which:

-

[VIIII viri] Val(etudinis) viam a porticu ad m[acellum? straverunt]

-

✴Merula’s funerary inscription (CIL XI 5400, now also in the Museo Archeologico) records that, over his life, he gave (inter alia) 37,000 sesterces to the municipal treasury of Asisium for the paving of streets (which presumably included the street from the cistern to the house of Lucius Mutius, above). According to Margaret Laird (referenced below, at p. 235):

-

“... Eros Merula’s gift could have surfaced [ca. 480 meters] of Asisium’s streets. Because the distance between Asisium’s main public monuments and the city’s walls rarely surpasses 300 meters, Merula could have paved several stretches throughout the town.”

In short, if we accept that role of the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis at Mevania was essentially the same as that of the seviri at Asisium, then the natural conclusion is that the “viam a porticu ad m...” of CIL XI 5040 was most probably an urban street.

I am not arguing here against Simone Sisani’s proposition that there was a processional route from Mevania to the Fonti del Clitunno that dated back to the pre-Roman period, when Mevania owned the sanctuary there. What I am arguing is that there is no particular reason to associate this putative processional route with the Augustan paving project evidenced by CIL XI 5040.

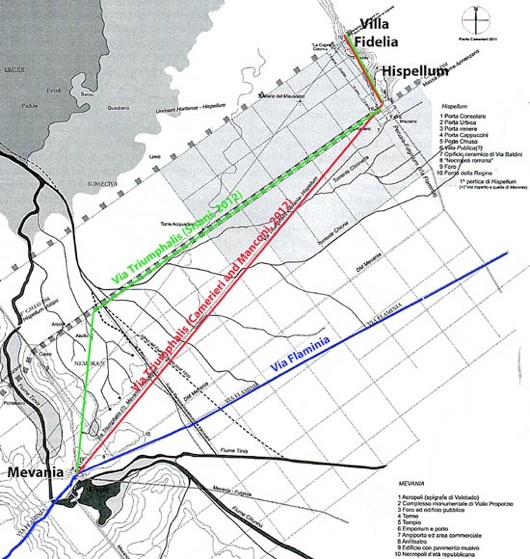

CIL XI 5041: Via Triumphalis

Possible route of the via triumphalis mentioned in CIL XI 5041

Adapted from Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, 2012, Figure 17)

(The route in green is as proposed by Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, Figure 13)

As discussed above, the inscription CIL XI 5041 records that the magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis paved a road that was known as the via triumphalis, using stone from Hispellum. The inscription was found inside Porta Cannara, in front of the church of San Francesco (marked on the plan above). Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 416) observed that:

-

“This name [via triumphalis], which is unknown anywhere else except Rome, alludes without doubt to a processional route” (my translation).

There is some uncertainty as to the date of the inscription:

-

✴Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 416) dated it on paleographic grounds to the “primissima età imperiale” (i.e. to 27 BC or shortly thereafter); while

-

✴the EAGLE database (see the CIL link above) gives a later date, in the first three decades of the 1st century AD.

Possible route of the via triumphalis mentioned in CIL XI 5041

Adapted from Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, Figure 13)

Simone Sisani suggested (at pp. 417-8) that the via triumphalis began at a point close to the find spot of the inscription, and then followed a route (illustrated above) that:

-

✴included a stretch of road (which was apparently paved in stone from Spello) that has been excavated along the western edge of the cult site on Via I Maggio/ Viale Properzio (also described by Simone Sisani, referenced below, 2006, at pp. 90-1);

-

✴continued northwards for about 2 km as far as the sanctuary at the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo (which, as discussed below, he suggested was dedicated to Valetudo);

-

✴(turning now to his description at p. 428 and at p. 431), turned northeast along the decumanus maximus of Hispellum to Porta Consolare; and

-

✴then turned left (along what was probably another processional road) to the sanctuary at what is now Villa Fidelia, a sanctuary that had almost certainly been transferred from Mevania the new colony of Hispellum in 41 BC.

The first two of these sanctuaries are discussed in a section below, while the third is discussed in my page Spello: Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia.

Sisani’s proposed route for the first part of the via triumphalis relies largely on archeological evidence:

-

✴the excavated road along the western edge of the cult site on Via I Maggio/ Viale Properzio, which might have been part of a road that linked the find spot of the inscription to the sanctuary at the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo; and

-

✴the fact that the latter sanctuary was monumentalised at about the time that the via triumphalis was paved.

While this evidence is suggestive, it is by no means definitive: note, for example, the route proposed by Paolo Camerieri and Dorica Manconi (referenced below, 2012, Figure 17).

The evidence for Sisani’s proposed destination of Villa Fidelia is circumstantial, and relies heavily on the assumed significance of its name. This line of reasoning is best illustrated by extracts from two earlier papers:

-

✴Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, at p. 496) argued that:

-

“The ritual nature of [via triumphalis at Mevania] is clear from its name: this is a unique parallel to the [via triumphalis] in Rome, which was associated with the [Roman] victories over the Etruscan city of Veii and with the archaic triumph. In the light of what we know about the oldest ‘Latin’ triumph, which had as its destination the federal sanctuary of Monte Albano, the [putative ancient] via triumphalis of Mevania can be identified with the road that linked Mevania, perhaps the political capital of the [putative Umbrian] League [in the 4th century BC], to the [putative] federal sanctuary that was located at nearby Hispellum” (my translation).

-

✴Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, at p. 48), who cited this paper by Sisani, reached broadly the same conclusion:

-

“[The via triumphalis at Mevania is] the only example of this denomination that we know outside Rome. The route of the triumph at Rome started at the sanctuary of Sant’ Omobono (the site of the temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta) and ended at the temple of Jupiter on the Capitol. In the case [of Mevania], the point of departure was probably a temple of Valetudo - probably a Roman interpretation of an Umbrian deity of virtus (bravery and military strength) as well as sanatio (healing) - while the point of arrival was at the sanctuary at Villa Fidelia, dedicated to Jupiter and Venus. The model, for both Rome and Mevania, was probably the sanctuary of the fanum Voltumnae at Volsinii, the centre of the Etruscan League and dedicated to the cult of (Tinia) Veltumna, the principal god of the Etruscans” (my translation).

These hypotheses put forward by Sisani and Coarelli can be reduced to two fundamental propositions:

-

✴that the Augustan via triumphalis at Mevania must have followed a route used in the the triumphal ritual of a putative Umbrian League (a ritual that would have been redundant after the Roman conquest in 308-295 BC); and

-

✴that this ancient route must have connected Mevania (the putative capital of this Umbrian League) to the putative federal sanctuary at Villa Fidelia.

The obvious point to make is that our knowledge of ancient triumphal ritual in Italy is hardly comprehensive:

-

✴The Roman ritual might have originated with the Etruscans at the fanum Voltumnae, but we have only circumstantial evidence to this effect.

-

✴The Umbrians might also have adopted Etruscan practice, but again, there is no evidence that this was the case, or indeed that the Umbrian tribes ever shared a triumphal ritual of any kind.

-

✴If they had such a ritual, it is not clear (at least, to me) that its destination would have been an ancient sanctuary at Villa Fidelia (for which the archeological evidence is slight) rather than, for example, the sanctuary of Clitumnus/ Jupiter at the Fonti del Clitunno, which (as noted above) probably belonged to Mevania until 241 BC.

Furthermore, both Sisani and Coarelli argue that there is no other explanation than theirs for an Augustan via triumphalis at Mevania, but this is surely too bold: for example, Paolo Camerieri (referenced below, at pp. 89-90) suggested that the via triumphalis might have evoked the route that Quintus Fabius Maximus Rullianus took from his camp on the site of modern Foligno when he entered Mevania after his triumph of 308 BC.

In my opinion, this road had nothing to do with the triumphs of ancient times: rather, I argue in my page on Spello: Colonia Julia Hispellum (scroll down to the section on the Santuary at Villa Fidelia) that a via triumphalis from Mevania to the pan-municipal Augustan sanctuary at Villa Fidelia (which had been built soon after Augustus’ triple triumph of 29 BC), probably constituted a processional route used for public thanksgiving after later victories secured by Augustus himself and members of his family. It seems to me that the veterans and other supporters of Augusts who now provided the leading men of the municipia of the Valle Umbra, many of whom were from places outside Umbria, would surely not have needed memories of ancient Umbrian ritual to inspire them to create a processional route that would be used for celebrations of this kind.

In short, I think that the generally held view, that the via triumphalis of CIL XI 5041 was a processional route that linked Mevania to the Augustan sanctuary at Villa Fidelia, is almost certainly correct. However, I think it was used in processions associated with Augustan victories, and that its route is unlikely to have been inspired by communal memories of Umbrian ritual of the pre-Roman period, for which there is no surviving evidence.

Sanctuaries Dedicated to Valetudo ?

Two sanctuaries outside Mevania (both discussed in more detail in my page on Other Sanctuaries of Mevania) have been linked by scholars to the cult of Valetudo.

Sanctuary in Via I Maggio/ Viale Properzio ?

According to Giuseppina Prosperi Valenti (referenced below, 2005, entry 1), the Mensa dei Magistri Valetudinis, which carries the inscription CIL XI 7926 (described above), was found in the early 20th century outside the walls of Mevania, between Porta Cannara and Porta Foligno. She observed that this presumed find spot was close to a number of other important archeological discoveries, which included:

-

“... a fountain in an important sacred area [marked “Sanctuary in Via I Maggio/ Viale Properzio” in the plan above] dating to the mid-Republican period ...; this complex was restored and extended by the construction of a second fountain in the reign of the Emperor Hadrian ... [at around the likely date of] the altar of the magistri Valetudinis. This ... has induced scholars to identify the [sanctuary] as having been dedicated to Valetudo” (my translation).

It is certainly possible that the water that fed the fountains of this sanctuary was believed to be of therapeutic value, which might suggest a dedication to Valetudo. However, the hypothesis put forward by Prosperi Valenti is probably less securely-based than she believed:

-

✴the find spot of the altar seems to have been slightly further from the sanctuary than she thought:

-

•Carlo Pietrangeli (referenced below, at p. 94) placed it on the opposite side of Porta Foligno, in the location on Via Flaminia marked in the plan above (see also his map at p. 67, in which it is located at number 5); and

-

•this location is also given in the EAGLE database (see the CIL link above); and

-

✴this database dates the inscription to the first half of the 2nd century AD, thus weakening the evidence for its chronological link with the restoration of the sanctuary.

Sanctuary at the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo ?

Matelda Albanesi and Maria Romana Picuti (referenced below, at p. 169), in their paper on the excavation of the sanctuary at the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo, pointed out that:

-

“... Mevania [presents evidence of] a remarkable concentration of deities related to the sphere of health, such as Hygeia, Aesculapius and Valetudo, and one cannot exclude the possibility that the sanctuary at the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo may be connected in some way with the last of these, a deity that was probably of Umbrian origin and linked to [therapeutic] springs and the sphere of sanatio (healing)” (my translation).

They noted (at note 196) the suggestion of Filippo Coarelli (above), that Valetudo was probably a Roman interpretation of an Umbrian deity of virtus (bravery and military strength) as well as sanatio, and suggested that :

-

“... perhaps this peculiarity of the cult can be traced [in two finds from the site] that attest to the attendance of soldiers and gladiators at this sacred place” (my translation).

These finds were:

-

✴a silver disc embossed with a relief of the deity Victory (illustrated in their paper as Figure 28), which was probably a votive offering made by a soldier, perhaps in the reign of the Emperor Trajan (98 - 117 AD); and

-

✴a head made of lead, from the 3rd century AD (illustrated in their paper as Figure 30), which probably represented a gladiator.

However, these objects are relatively late, and Albanesi and Picuti certainly did not claim them as conclusive proof that the sanctuary was dedicated to Valetudo (whether in the archaic period, the Augustan period, or thereafter).

As noted above, Simone Sisani (2012, referenced below, at p. 420) suggested that the via triumphalis (discussed above) linked the sanctuary at the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo to the sanctuary in Via Maggio I/ Viale Properzio. He expounded (at pp. 418-9) on the significance of this topography as follows:

-

“The entire area [around the the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo and the nearby Lago dell’ Aiso] originally hosted a complex organic structure of rural sanctuaries, where water clearly played a central role that was significantly replicated at the opposite end of the via triumphalis, in the system of fountains that articulated the sacred area of Viale Properzio {just outside the walls of the Roman city]” (my translation).

He then suggested that:

-

.. the model for these [distributed] sanctuaries is likely to have been the sanctuary at the source of the Clitumnus, which Pliny vividly described as a series of springs, each of which had its own cult and its own small temple. Since the source of this river and the eponymous god Clitumnus acted as ‘parens’ in relation to the other cults - according to the striking metaphor used by Pliny - then, in my opinion, the main deity worshiped in the sanctuary at the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo was Valetudo, as suggested ... by the particular interest that the magistri Valetudinis took in the processional route that was directed towards it” (my translation).

It is not clear to me why Sisani believed that the sanctuary at the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo, rather than that on Viale Properzio, was the ‘parens’ of this putative sacred complex, but I assume that this was because it was closer to the source of the therapeutic water that fed them both. Sisani further suggested (at p. 419) that the deities Clitumnus/ Jupiter and Valetudo were linked in two specific contexts:

-

✴through their respective associations with the therapeutic qualities of water; and

-

✴as a male/female pair associated with ancient triumphal ritual, known:

-

•in Rome (Jupiter Optimus Maximus/ Fortuna):

-

• in Lazio (Jupiter Latiaris/ Ferentina); and

-

•possibly in Etruria (Tinia Voltumna/ Nortia ?).

-

These associations were only touched on in Sisani’s paper of 2012, but with a reference (at note 63) to the detail provided in his earlier paper (referenced below, 2002, see, in particular, to his table at p. 498).

I have considerable doubts about this hypothesis:

-

✴It is, of course, possible that the sanctuary at the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo was part of a distributed complex that was modelled on that at the Fonti del Clitunno, but there is no direct evidence that this was the case.

-

✴Simone Sisani’s assumed link between:

-

•the god Clitumnus and the sanctuary at the Fonti del Clitunno on the one hand; and

-

•the goddess Valetudo and the sanctuary at the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo on the other;

-

is based on his related assumption that Valetudo, like Clitumnus, was an ancient Italic deity and that she was a goddess of both health and victory. However, I argued above that she was more probably a Roman deity of more recent origins and that there is no evidence that she was ever venerated as a bringer of victory. Thus, even if one accepts that the sanctuary the Laghetto dell’ Aisillo was in some ways a parallel to the sanctuary of Clitumnus (and perhaps linked to it by an ancient processional route), this would not be a secure basis for the hypothesis that it was dedicated to Valetudo.

-

✴Magistracies such as the magistri Valetudinis frequently financed the paving of roads with which they had no particular association (as discussed above). It is true that the extra-urban via triumphalis at Mevania might have been an exception, but this is by no means beyond question.

Conclusion

It seems to me that the evidence of CIL XI 5041 alone cannot conclusively link Valetudo to the either of the sanctuaries on the presumed route of the via triumphalis. It is true that both of these sanctuaries were probably associated with the therapeutic qualities of water, but that, in itself, is not conclusive proof of a dedication to Valetudo. It seems to me that there is no hard evidence that either of them was dedicated to Valetudo.

Other Magistracies at Mevania

Seviri Sacris Faciundis

As noted above, three surviving inscriptions from Bevagna relate to men who were both magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis and seviri sacris faciundis:

-

✴the freedman Caius Arruntius (CIL XI 5044, 1st century AD);

-

✴Cnaeus Serius Philetus (CIL XI 5053, 2nd half of the 1st century AD), who was probably a freedman or descended from one; and

-

✴the freedman Caius Attius Ianuarius (CIL XI 5047, 2nd century AD), who was also a member of a professional guild, the collegio dei centonarii.

Two other surviving inscriptions relate, or possibly relate, to men who held the latter but not the former position, although their names are unfortunately lost:

-

✴A (now lost) fragmentary inscription (AE 1965, 279a) from Montefalco commemorated a man whose name is missing from the top of the stone. The surviving part of the inscription read:

-

]Q VI VIR SAC[R?][...

-

]AEST MARONI I[...

-

[M]UNICIP(ES) ET INC[OLAE]

-

Elena Roscini (in L. Agostiniani et al., referenced below, entry 78, pp. 86-7) dated this inscription to the early Augustan period (i.e. to the early part of 27 BC - 14 AD). The problematic post of ‘marone’ discussed in my page on Mevania after the Perusine War: it is clear from his post of quattuorvir quinquennial (the likely completion of “]Q” in the 1st line) that he was free born. Of interest here is/are his post(s) “VI VIR SAC[R?][...” recorded in remainder of the first line of the inscription. As Laura Bonomi Ponsi (in A. Feruglio et al., referenced below, at pp. 85-6; entry 2:121) pointed out, only the upright of the letter assumed to be ‘R’ survives:

-

•If it is indeed an ‘R’,then the post is reasonably completed as sevir sacris faciundis.

-

•However, it could be an ‘E’, in which case the subject would have held the separate posts of sevir (see below) and sacerdote (priest).

-

✴A fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 7932) from Bevagna [find spot? present location? date?] commemorates a now-anonymous:

-

] / [sex]vir/ [sa]c(ris) fac(iundis)

The title of the seviri sacris faciundis (literally, six men responsible for the sacred rites) implies that they had a religious function (as did the important quindecemviri sacris faciundis at Rome). Unfortunately, we have no evidence upon which to determine the precise nature of the presumed religious duties and cult activities of the seviri sacris faciundis at Mevania. What we can say is that, despite the fact that the priesthood was open to freedmen, it was quite probably distinct in its functions from the ‘civic’ or secular magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis here.

Seviri and Augustales

Seven surviving inscriptions from Bevagna refer (or might refer) to seviri.

-

✴Two of these commemorate men from the Lemonia tribe and thus probably pertain to veterans settled on land belonging to Hispellum:

-

•A funerary inscription (CIL XI 5275; 27BC - 14AD) from Fiamenga ( midway between Bevagna and Foligno), which is now in the Museo Archeologico at Palazzo Trinci, Foligno, commemorates Cnaeus Decimius Bibulus, an evocatus of the 13th legion and VIvir.

-

•A now-lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5286), 20BC - 20AD) from Fiaggia (some 5 km northwest of Bevagna) commemorated the sevir Titus Statius.

-

These two seviri are discussed in my page on Spello: Seviri and Seviri Augustales at Hispellum.

-

✴The other five inscriptions, which probably all pertain to Mevania, are as follows:

-

•As discussed above, the unknown free born man commemorated in AE 1965, 279a (early Augustan period) from Montefalco could have been either a sevir or a sevir sacris faciundis.

-

•A funerary inscription (CIL XI 5051, 27 BC - 14 AD) that was found in an unknown location in Bevagna (now in the Museo Archeologico) commemorates the free born Titus Eleurius son of Titus, of the Aemilia tribe, as “X(?)vir”, which is sometimes construed as sexvir.

-

•A now-lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 5052, 27 BC - 14 AD) that was found in an unknown location in Montefalco commemorated the free born Caius Pisentius, son of Lucius as VIvir.

-

•A now-lost funerary inscription (CIL XI 7930, 10BC - 10AD) that was found at Cantalupo, some 4 km northwest of Bevagna, commemorated the freedman Cnaeus Trebatius as sevir.

-

•A fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 7929,1st century AD) that was found in Piazza Silvestri (now in the Museo Archeologico) reads:

-

C(ai-) F+[---]/ VI[---]/ aed[---]

-

where VI[---] could be completed as VIvir or VIIIIvir. The subject’s post of aedile indicates that he was free born.

Carlo Pietrangeli (referenced below, at p. 42, note 152) suggested that the post indicated as sevir in inscriptions from Mevania was simply an abbreviated form of sevir sacris faciundis. However, it could alternatively have belonged to a separate college of seviri (the equivalent magistracy at Asisium discussed above). Of the five men in this group, only Cnaeus Trebatius of CIL XI 7930 was identified as a freedman. It is possible that the relative frequency of freeborn men in these inscriptions is associated with their relatively early dates, although it is also possible that practice at Mevania followed that at Hispellum in this area.

For completeness, I should also include here a fragmentary inscription (AE 1989, 0278, 70-150 AD), which was found in an unknown location in Bevagna (now in the courtyard of the house at at 9 Via San Francesco). It reads:

[---]eno/ [---]ilo/ Aug(ustali)/ Tertulla

Henrik Mouritsen (referenced below, at p. 238, note 5) observed that:

-

“Whether [this inscription] ... really proves the existence of [Augustales] at Mevania remains uncertain”.

Although this body of evidence is difficult to interpret, we cannot rule out the coexistence at Mevania of magistri/ novemviri Valetudinis, seviri and possibly Augustales, all of which would have had largely civic and secular functions. This would not have been unusual: Henrik Mouritsen (referenced below, at pp. 239-40), for example, produced a list of 17 Italian municipia where two of more magistracies of this type were recorded. (These municipia included Patavium (Padua), discussed above.)

Read more:

P. Camerieri, “Il Castrum e la Pertica di Fulginia in Destra Tinia”, in:

G. Galli (Ed.), “Foligno, Città Romana: Ricerche Storico, Urbanistico e Topografiche sull' Antica Città di Fulginia”, (2015) Foligno, pp. 75-108

M. Laird, “Civic Monuments and the 'Augustales' in Roman Italy”, (2015 ) New York

P. Camerieri and D. Manconi , “Il ‘Sacello’ di Venere a Spello: dalla Romanizzazione alla Reorganizzazione del Territorio: Spunti di Ricerca ", Rivista di Antichità, 21 (2012) 63-80

S. Sisani, “I Rapporti tra Mevania e Hispellum nel Quadro del Paesaggio Sacro della Valle Umbra”,, in

G. della Fina (Ed.), “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, (2012) Orvieto (pp. 409-64)

M. Albanesi and M. R. Picuti, “Un Luogo di Culto d’ Epoca Romana all’ Aisillo di Bevagna (Perugia)”, Mélanges de l’École Française de Rome, 121 (2009) 133-179

T. Stek, “Cult Places and Cultural Change in Republican Italy”, (2009) Amsterdam

E. Bispham, “From Asculum to Actium: The Municipalisation of Italy from the Social War to Augustus”, (2008) Oxford

A. Clark, “Divine Qualities: Cult and Community in Republican Rome”, (2007) New York

E. Zuddas, “Asisium: Aggiunte e Correzioni ai Monumenti Epigrafici Compresi nelle Raccolte che si Aggiornano”, Supplementa Italica, 23 (2007) 268-347

H. Mouritsen , “Honores Libertini: Augustales and Seviri in Italy”, Hephaistos, 24 (2006) 237-48

S. Sisani, “Umbria Marche”, (2006) Rome/ Bari

G. Prosperi Valenti, “I Magistri Valetudinis di Mevania” Bollettino della Deputazione di Storia Patria per l’ Umbria, 102:1 (2005) 27-58

S. Sisani, “Lucius Falius Tinia: Primo Quattuorviro del Municipio di Hispellum”, Athenaeum, 90.2 (2002) 483-505

F. Coarelli, "Il Rescritto di Spello e il Santuario ‘Etnico’ degli Umbri”, in:

“Umbria Cristiana: dalla Diffusione del Culto al Culto dei Santi,” Atti del XV Congresso Internazionale di Studi sull’ Alto Medioevo, (2001) Spoleto, pp. 39-52

M. Beard et al., “Religions of Rome: Volume 2: A Sourcebook”, (1998) Cambridge

G. Prosperi Valenti, “Valetudo: Origine ed Aspetti del Culto nel Mondo Romano”, (1998) Rome

C. Letta, “I Culti di Vesuna e Valetudo tra Umbria e Marsica” in

G. Bonamente and F. Coarelli (Eds.), “Assisi e gli Umbri nell' Antichità: Atti del Convegno Internazionale (Assisi, 18-21 Dicembre 1991)”, (1996) Assisi

A. Feruglio et al. (Eds), “Mevania: Da Centro Umbro a Municipio Romano”, (1991) Perugia

A. Chastagnol et al, (Eds.), “L'Année Épigraphique: Année 1987”, (1990), pp. 51-128

L. Lazzaro, “Schiavi e Liberti nelle Iscrizioni di Padova Romana”, Annales Littéraires de l'Université de Besançon, 404 (1989) 181-95

C. Pietrangeli, “Mevania”, (1953) Rome

H. Mattingly, “A Rare Coin of Augustus”, The British Museum Quarterly, 7:1 (1932) 12-13

Ancient History: Pre-Roman Mevania Fonti del Clitunno

Mevania after the Conquest Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia before 41 BC Other Sanctuaries

Mevania after the Perusine War Valetudo and the Magistri Valetudinis

Return to the page on History of Bevagna