Early Habitation of Mevania

The remains of a house with dry stone walls from the 7th century BC were excavated in 1980-2 in Via I Maggio, near the junction with Viale Properzio, just outside the present city walls. These are the oldest stone buildings that have been found in Umbria. These excavations also uncovered a furnace, which suggests that the this was a centre of ceramic production from a very early date, presumably based on the rich clay deposits that still characterise the area. Other finds from these excavations that are exhibited in the Museo Archeologico, Perugia include:

-

✴an architectural decoration in the form of a gargoyle in the shape of a cat’s head;

-

✴a number of impasto and bucchero pottery fragments; and

-

✴a loom weight.

A number of ditch tombs excavated in the area belonged to this 7th century community.

-

✴Three were found on the Viale Properzio site itself.

-

✴Other tombs were found in ca. 1909 in Vigna Boccolini, a site on the later Via Flaminia, some 500 meters from Porta Foligno.

-

✴Two more were found in ca. 1880 on the road to Todi, one of which contained two bronze discs that now form part of the Guardabassi Collection in the Museo Archeologico, Perugia.

It is likely that this early community was one of many in the area that were loosely associated through the use of common cult sites:

-

✴Bronze votive statues of warriors that are displayed in the Museo della Città (including one that was found on the road to Foligno) suggest that the cult of Marte (later Mars) might have existed in the area (as it did, for example, around Todi).

-

✴Bronze votive offerings (6th - 5th century BC) that were found by the Lago dell’ Aiso, to the north of Bevagna suggest that this was probably a cult site, perhaps devoted to a river god. This small, deep freshwater lake, whose name derives from the word for abyss, remained a place of superstition well into modern times.

The hill fort and temple on Monte delle Civatelle (to the west, near modern Poggio della Civitella) might also have been used by this community.

This polychromed terracotta antefix (4th century BC), which was found in the 1990s in Parco Silvestri, outside Porta Foligno, presumably came from the temple that was discovered here in 1884. (The original excavations are documented, but no visible trace of the temple survives. The antefix is now in the

Museo Archeologico, Perugia.)

Mevania was later to become the only major settlement on the western spur of Via Flaminia (ca. 220 BC), discussed on the next page. This road ran along the present Corso Matteotti, from Porta Sant' Agostino to Porta Foligno. It passed necropolises outside each of these gates that had been in use since the 4th century BC, which suggests that it followed the route of an earlier road that had served the already urbanised society in the pre-Roman period.

Mevania and the Valle Umbra

Rivers of Mevania

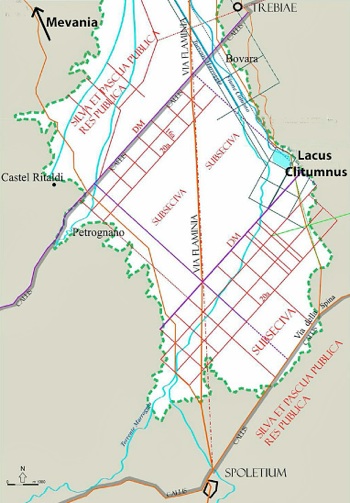

Adapted from Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, Figure 13

Mevania stood on a slightly elevated site in the water-logged Valle Umbra, between the Lacus Umber to the north and the Lacus Clitorius to the south.

Timia at Porta Todi, Bevagna

It was also almost surrounded by rivers:

-

✴the Clitumnus (Clitunno) and Teverone from the south east and the Tinea (Topino) from the east met on the eastern side of the settlement, forming a riverine basin that is still evidenced by a depression outside the city walls near Porta Molini; and

-

✴a river that is now known as the Timia flowed northwards from this riverine basin, passing Cannara and Bettona to Torgiano, where it flowed into the Tiber.

A number of literary sources help us to envisage the ancient river system:

-

✴Writing of the Topino in 7 BC, Strabo referred to:

-

“... Mevania, past which flows the [Topino, which] brings the products of the plain down to the Tiber on rather small boats” (‘Geography’, 5:2:10).

-

Thus, Strabo seems to have regarded the river now known as the Timia as a continuation of the Topino. The course of the Topino has been transformed by a series of drainage projects undertaken since at least Roman times, and it was finally diverted to the north of Bevagna in the 17th century. It now joins the Timia near Cannara, before both flow on into the Tiber.

-

✴The Clitumnus still emerges from limestone rocks into a lake at Campello del Clitunno (illustrated below), from which point it once meandered northwards through some 16 km of the fertile plain of Mevania. This stretch of the river was original navigable: it has been much reduced by seismic activity and human intervention and is now almost completely canalised. Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 440, entry 1:12) quoted an unknown commentator on Virgil’s ‘Georgics,’ who noted that:

-

“In Umbria, Clitumnus is a god, and [also] the name of the river that flows into the Tiber” (my translation).

-

Sisani commented (at p. 412) that:

-

“ ... at least for this author, the name of the river applied to a hydrology more extensive than that of today, and included not only the present course of Clitunno [south of Bevagna], but also that of the present Timia [from Bevagna to the Tiber]” (my translation).

-

In other words, this unknown commentator considered the Topino and the Teverone to have been tributaries of a single river, the Clitumnus.

Thus, Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 414) summarised:

-

“The correct reconstruction of the hydrography of the ancient Valle Umbra allows us to understand intuitively the centrality of the river Clitumnus in this territorial context: considering [its entire course from its source at Campello del Clitunno] as far as its confluence with the Tiber, it was undoubtedly the longest river (about 40 km) of the entire [Valle Umbra]. It must also have been much wider than today [based on the testimony of Pliny the Younger, see below]” (my translation).

The River God Clitumnus

The god Clitumnus featured in the work of two of the great lyrical poets of the 1st century BC:

-

✴Propertius:

-

“I'll go hunting ... where [the god] Clitumnus covers the beautiful stream with his own woods, and his wave bathes the snow-white heifers” (‘Elegies’, 2:19).

-

✴Virgil:

-

"... here are your snowy flocks, Clitumnus and, the noblest sacrifice, your bulls, which, drenched in your sacred stream, have often led Roman triumphs to the gods’ temples" (‘Georgics’, 2:136).

These are among the earliest surviving references of the association of the river with the deity whose name it bore.

Vibius Sequester, in his ‘De fluminibus’ (‘On Rivers’, an annotated lists of geographical names, written in the 4th century AD)), in which he recorded the:

“Clitumnus Umbriae, ubi Iuppiter eodem nomine est”

river Clitumnus in Umbria, where Jupiter has the same name (my translation)

Thus it seems that the Umbrian river god Clitumnus was, in some respects, a manifestation of Jupiter.

Pliny the Younger described a cult site at the source of the Clitumnus that was devoted to the river god of the same name:

-

“Near [the source of the Clitumnus] stands an ancient and venerable temple, in which is placed [a cult statue of] the river-god Clitumnus clothed in the usual robe of state; and indeed, the prophetic oracles here .... testify to the immediate presence of that divinity. Several little chapels are scattered round, dedicated to particular gods, distinguished each by his own peculiar name and form of worship, some of them also presiding over different springs. For, besides the principal spring, which is ... the parent of all the rest, there are several other lesser streams, which, taking their rise from various sources, lose themselves in the river” (Letter LXXXVIII to Romanus)

Pliny was writing in the 1st century AD, but it is likely that this sanctuary to Clitumnus at the source of ‘his river’ was of ancient origin.

Mevania and the Clitumnus

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 415) pointed out that:

-

“In the literary sources, the Clitumnus is always considered the river of Mevania, and its white bulls ... are defined as ‘mevanienses’” (my translation).

Sanctuary of Clitumnus and its Sacred Grove

Fonti del Clitunno

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 415) asserted that:

-

“The association of the [Clitumnus] with Mevania .. extended, at least originally, to the very source of the river, as explicitly supported by Vibius Sequester ...” (my translation).

Here, Sisani alluded to the fact that Vibius Sequester included the “Clitumnus mevaniae” in his “De fontibus” (on river sources), which places even the the source of the river in the ownership of Mevania.

The description that Pliny the Younger included in a letter he wrote after visiting the source of the Clitumnus in the 1st century AD remains invaluable:

-

“Near [the source of the Clitumnus] stands an ancient and venerable temple, in which is placed the river-god Clitumnus, clothed in the usual robe of state; and indeed the prophetic oracles here .... testify to the immediate presence of that divinity. Several little chapels are scattered round, dedicated to particular gods, distinguished each by his own peculiar name and form of worship, some of them also presiding over different springs. For, besides the principal spring, which is ... the parens (parent) of all the rest, there are several other lesser streams, which, taking their rise from various sources, lose themselves in the river, over which a bridge is built that separates the sacred part from that which lies open to common use. Vessels are allowed to come above this bridge, but no person is permitted to swim except below it” (Letter LXXXVIII to Romanus).

Thus, the temple Clitumnus at the heart of the sanctuary was already ancient in the 1st century AD. The cult site was still in use, separated by a bridge from what seems to have been a popular centre for leisure activities further upstream.

Lex Spoletina (CIL XI 4766), Museo Archeologico Spoleto

Two archaic Latin inscriptions (CIL XI 4766) in the Museo Archeologico of Spoleto

In an earlier paper (referenced below, 2007, p. 95), Sisani pointed out that the cippi that had been inscribed with the so-called lex Spoletina, which governed the use of a wood or grove that was sacred to Jupiter, had been found:

-

“ ... immediately to the west of the Fonti del Clitunno and can indeed be identified as belonging to the sanctuary of Clitumnus, whose identification with Jupiter [recorded by Vibius Sequester, above] is perfectly consistent with the mention of Jupiter in connection with the [propitiatory fine demanded by the lex Spoletina]” (my translation)

Thus, if Sisani is correct, Mevania had originally owned both the sanctuary at the source of the Clitumnus and the nearby sacred grove. (The sanctuary and the grove are discussed in my page on the Fonti del Clitunno).

Both the sanctuary and its sacred grove were transferred to the new colony of Spoletium soon after its deduction in 241 BC (as discussed in my page on Roman Mevania). John Scheid (referenced below, at pp. 79-80) placed this apparent confiscation in a wider political context:

-

“After the definitive submission [to Rome] of the Latins in 338 BC, three important [Latin] cult sites passed definitively under Roman control:

-

-the federal sanctuary of the Latins on Monte Cavo [also called Monte Albano, in the Alban Hills near Rome] was now a Roman cult site, and the Feriae Latinae were also celebrated at Rome during the federal meetings at Monte Cavo;

-

-the temple of Juno Sospes at Lanuvium [south of Rome] became a common cult site of the Romans and the Lanuvins; and

-

-at Lavinium [near modern Ostia], many annual rites were celebrated by the Lavinates and the magistrates and priests of Rome.

-

Another example is offered by the Umbrian cult site at the source of the Clitumnus ... [which was] manifestly one of the great religious sites of the Valle Umbra. ... Since it was located near Mevania, it seems likely that it was controlled by the Umbrians from Mevania itself or the surrounding area. When the Latin colony of Spoletium was founded in 241 BC, the cult site clearly passed to it, since it was later found on the boundary of the pertica of Spoletium. ... It was in this way that the Romans used the colony as an intermediary to control the places of memories and of regional reunions of the Valle Umbra” (my translation).

Thus, by analogy, Scheid saw the sanctuary at the Fonti del Clitunno as a communal sanctuary, a proposition that I discuss this further below.

Unfortunately, we have no evidence (other than the apparent appropriation of the sacred grove) to suggest how the use of the site changed after its transfer to Spoletium.

Sanctuary at the Fonti del Clitunno

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 415) suggested that:

-

“[The following three characteristics]:

-

-the centrality of the [river Clitumnus, in its original form] in the context of the entire Valle Umbra;

-

-the association of its divinity [i.e. Clitumnus] with Jupiter; and

-

-the association of this divinity with [the ritual of triumphs];

-

... allow us to postulate a close functional analogy between Jupiter/ Clitumnus and, for example, Jupiter Latiaris of the Latin League [centred on the Alban Mount], leaving no doubt about the ethnic relevance of the cult [of Clitumnus at the Fonti del Clitunno] certainly common to all the Umbrian nomen” (my translation).

Tim Cornell (referenced below, 2012, at p. 795, entry for ‘Latini’)) gave a useful summary of the key characteristics of the cult of Jupiter Latiaris and the importance of the cult site on Monte Albano in relation to the Latin nomen:

-

“From the earliest times, the Latins formed a unified and self-conscious ethnic group with a common name (the nomen Latinum), a single language, and a common material culture ... Their shared sense of kinship was expressed in a myth of common ancestry. According to this legend, the Latins traced their origin to a union of Trojan refugees [led by Aeneas] with the native Aborigines, whose king, Latinus, gave his name to the resulting amalgam ... After his death, Latinus was transformed into Jupiter Latiaris and worshipped on the Alban Mount. ... The annual celebration of this cult, known as the ... Feriae Latinae, was an assembly of representatives of all the Latin communities ... each of which contributed items of produce to a banquet: a white heifer was sacrificed and the meat shared among all the participants. ... Participation in the cult was a definition of membership: the Latins were [by definition] those people who received meat at the annual festival ...”

We might reasonably ask whether the three characteristics of the sanctuary of Clitumnus enumerated by Sisani (above) really are close enough to the key characteristics of the sanctuary of Jupiter Latiaris to:

-

“ ... leave no doubt about the ethnic relevance of the cult [at the Fonti del Clitunno, which was] certainly common to all the Umbrian nomen.”

Taking them in turn:

-

✴The river Clitumnus, like the Alban Mount, was arguably the most prominent feature in its geographical context. However, in the former case, this context only embraced the people of the Valle Umbra (as discussed further below).

-

✴Vibius Sequester, our source for the information that Clitumnus was a manifestation of Jupiter, was writing in the 4th century AD. We do not know whether this had been true in the pre-Roman period, or whether it had perhaps been associated with the transfer of the sanctuary to Spoletium.

-

✴Neither Jupiter Latiaris nor Clitumnus can be securely linked to triumphal ritual in the pre-Roman period:

-

•It is true that, on at least four occasions in the early Republic, Roman consuls celebrated triumphs at the sanctuary on Monte Albano, probably because they had been denied this honour in Rome. However, according to Carsten Hjort Lange (referenced below, at p. 76), this did not represent:

-

“... a revival of an old Latin ritus: [in the pre-Roman period] the Latins, to our knowledge [I think he means ‘as far as we know’ rather than ‘to our certain knowledge’] never celebrated triumphs.”

-

Lange referenced some dissenting scholarship on this matter, but it is still fair to say that there is no hard evidence that the Latin nomen celebrated triumphs in the pre-Roman period, whether on Monte Albano or anywhere else.

-

•It is also true that white bulls raised on the banks of the Clitumnus were sacrificed to Jupiter during triumphs in Rome, at least from the late Republic. However (as fas as I know) there is no secure evidence that the Umbrian nomen (however defined) ever celebrated triumphs in the pre-Roman period, whether at the Fonti del Clitunno or anywhere else. (I argue in my page on Valetudo and the Magistri Valetudinis that the via triumphalis recorded in the inscription CIL XI 5041 from Mevania was probably an innovation from the time Augustus rather than a road that followed an ancient triumphal route).

More fundamentally, there is no evidence for an Umbrian nomen that had a shared foundation myth. There was certainly a shared language, for which there is epigraphic evidence across a an area far wider than the Valle Umbra (taking in, for example, modern Gubbio, Gualdo Tadino, Colfiorito, Nocera Umbra, Terni, Todi and Amelia). However, I am unaware of any evidence to suggest that the Umbrians outside the Valle Umbra participated in a shared cult at the Fonti del Clitunno.

On the basis of his opinion regarding the ethnic importance of Clitumnus, Sisani concluded (at p. 421) that:

-

“The controlling role that Mevania played in the political and religious life of the Valle Umbra [in pre-Roman times] emerges with absolute clarity ... The city [was] located on the Clitumnus at the point that was most propitious for the exploitation of its full potential, both economic and ideological. It occupied, from the time of its formation, a centrality that was expressed in what was probably its [Umbrian name], ‘Mefania’, which should be understood as 'the one who stands in the middle'. [In short], the city seems to have been configured in the pre-Roman period as the capital of a league based on ethnicity, whose sphere of influence spread across the entire Valle Umbra, if not beyond. The very existence of this type of association is presupposed by the dynamics that characterised the Umbrian opposition to the Roman advance into the region towards the end of 4th century BC” (my translation).

Of course, if the Clitumnus, as river and god, did not have particular relevance for the worship of the entire Umbrian nomen, then this argument for Mevania as a federal capital also falls away.

Pertica of Spoletium

Adapted from Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, Figure 2)

Having said that, it certainly seems likely that the sanctuary was used by the Umbrian communities of the Valle Umbra. As noted above, John Scheid (referenced below, at pp. 79-80) reached this conclusion in the light of the fact that it was transferred from Mevania to the new colony at Spoletium in ca. 241 BC, as shown in the diagram above:

-

✴Scheid pointed out that, after the final Roman conquest of the Latin nomen in 338 BC, three important Latin cult sites (the federal sanctuary on the Alban Mount and the cult sites at Lanuvium and Lavinium) had lost their purely Latin character, becoming cult sites shared with Rome.

-

✴He then suggested a similar process following the transfer of the sanctuary at the Fonti del Clitunno to Spoletium, which was then:

-

“... used by the Romans as an intermediary to control the places of memories and of regional reunions of the Valle Umbra” (my translation).

In fact, there were good strategic reasons for the establishment of a colony here, and the transfer the sanctuary might well have arisen simply because the river Clitunno offered a convenient means of defining the northeastern boundary of its pertica. Nevertheless, the Romans certainly ‘Latinised’ the sacred grove northeast of Castel Ritaldi (as evidenced by the lex Spoletina of CIL XI 4766, discussed above), and they might well have similarly adapted or even appropriated the cult and the sanctuary of Clitumnus.

Perhaps the best evidence that the sanctuary still remained a place “of memories and of regional reunions of the Valle Umbra” lies in the fact that Octavian transferred it to his new colony of Hispellum in ca. 40 BC (as discussed below).

On the basis of his opinion regarding the ethnic importance of Clitumnus, Sisani concluded (at p. 421) that:

-

“The controlling role that Mevania played in the political and religious life of the Valle Umbra [in pre-Roman times] emerges with absolute clarity ... The city [was] located on the Clitumnus at the point that was most propitious for the exploitation of its full potential, both economic and ideological. It occupied, from the time of its formation, a centrality that was expressed in what was probably its [Umbrian name], ‘Mefania’, which should be understood as 'the one who stands in the middle'. [In short], the city seems to have been configured in the pre-Roman period as the capital of a league based on ethnicity, whose sphere of influence spread across the entire Valle Umbra, if not beyond. The very existence of this type of association is presupposed by the dynamics that characterised the Umbrian opposition to the Roman advance into the region towards the end of 4th century BC” (my translation).

Of course, if the Clitumnus, as river and god, did not have particular relevance for the worship of the entire Umbrian nomen, then this argument for Mevania as a federal capital also falls away.

Roman Conquest (308 - 295 BC)

Mevania first appears in recorded history in a passage by Livy that describes a planned Umbrian invasion of Rome in 308 BC:

-

“The tranquillity now established in Etruria was interrupted by a sudden insurrection of the Umbrians, a nation which had suffered no injury from the war, except what inconvenience the country had felt in the passing of the army. These, by calling into the field all their own young men, and forcing a great part of the Etrurians to resume their arms, made up such a numerous force, that, speaking of themselves with ostentatious vanity and of the Romans with contempt, they boasted that they would leave Decius behind in Etruria, and march away to besiege Rome; which design of theirs being reported to the consul Decius, he removed by long marches from Etruria towards their city, and sat down in the district of Pupinia, in readiness to act according to the intelligence received of the enemy. Nor was the insurrection of the Umbrians slighted at Rome: their very threats excited tears among the people [of Rome], who had experienced, in the calamities suffered from the Gauls [in 387 BC], how insecure a city they inhabited. Deputies were therefore despatched to the consul Fabius [Quintus Fabius Maximus Rullianus] with directions that, if he had any respite from the war of the Samnites, he should with all haste lead his army into Umbria. The Consul obeyed the order, and by forced marches proceeded to Mevania, where the forces of the Umbrians then lay. The unexpected arrival of the consul ... so thoroughly affrighted the Umbrians that several advised retiring to their fortified towns; others, the discontinuing the war. However, one district, called by themselves Materina [an unknown location], prevailed on the rest, not only to retain their arms, but to come to an immediate engagement. They fell upon Fabius while he was fortifying his camp. [Fabius assembled his men and exhorted them] to finish this insignificant appendage to the Etrurian war, and take vengeance for the impious expressions in which these people had threatened to attack the city of Rome. [Such was the effect of this exhortation that his army stormed to victory and] the Umbrians called on each other, with one voice, to lay down their arms. Thus a surrender was made in the midst of action by the first promoters of the war; and, on the next and following days, the other states of the Umbrians also surrendered” (‘Roman History’, 9:41).

We might reasonably assume that Mevania itself was prominent in this Umbrian alliance, and thus that it was among the communities that surrendered to the Romans after this ignominious defeat. The Umbrians (or, at least, a significant Umbrian element) nevertheless subsequently allied themselves with the Samnites, and suffered a final blow to their independence with the Roman victory in the Battle of Sentium in 295 BC.

Was this a Rising of an Umbrian League ?

Near the start of the passage above, Livy asserted that Rome was faced by:

-

“... a sudden insurrection of the Umbrians, ... [who], by calling into the field all their own young men, and forcing a great part of the Etrurians to resume their arms, made up such a numerous force, that, ... they boasted that they would leave Decius behind in Etruria, and march away to besiege Rome; ... Nor was the insurrection of the Umbrians slighted at Rome: their very threats excited tears among the people ...”

According to Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2002, p. 493):

-

“The words ‘concitata omni iuventute sua’ [calling into the field all their own young men], used to describe the calling of the armies of the Umbrians, does not leave room for doubt: we must be dealing with the dilectus [compulsory conscription] of the entire nomen umbro [tribes of the Umbrian ‘name’] working within a league, as is also suggested by the use of the simple ethnic [‘Umbrian’] to describe the force opposing Fabius ...” (my translation).

Looking more widely at the Roman conquest of Umbria and Etruria in the 4th century and early 3rd century BC, Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 427) asserted that:

-

“... the little that we know about [the ancient] history of the region ... suggests a stable political-military alliance between the Umbrians and Etruscans from at least the beginning of the 4th century BC until the Battle of Sentinum [in 295 BC], directed against the common enemy [Rome]” (my translation).

I wonder whether we can really draw this conclusion from the surviving sources:

-

✴In the case of the Etruscans, Roman and Greek historians perpetuated the tradition of a federation of 12 city states that dated back at least to the days of Romulus. Livy recorded a series of meetings of this federation at a place that he called the fanum Voltumnae in the period 434-389 BC. However, these do not seem to have led to a concerted military response to the threat from Rome. Indeed, as Tim Cornell (referenced below, 1978, at p. 171) pointed out:

-

““... there is no historically verified instance in the literary sources of positive operations by a federal army organised by the Etruscan League [at any time]. It is true that, in 296BC, we hear [from Livy. ‘History of Rome’, 10: 16: 3] of a concilium [meeting] of the principes Etruriae [Etruscan leaders] that decided on war against Rome ... ; but, in this case, there is no evidence that the meeting was related to the [Etruscan League] ... or that it took place at the fanum Voltumnae. On the other hand there is clear evidence that relations between the Etruscan cities were characterised by instability and political enmity throughout the historical period ..., a fact that has led many scholars to suppose that the 'League' was a purely religious association.”

-

✴In the case of the Umbrians, they do turn up from time to time in Livy’s accounts, but the passage above relating to the events at Mevania in 308 BC is the only occasion that suggests concerted action by the Umbrian nomen (however defined). Livy certainly wanted to give the impression that the Umbrians had mustered a federal army, and also that they were capable of:

-

•forcing “a great part of the Etrurians” to resume hostilities and:

-

•reducing the Roman citizenry to “excited tears”.

-

However, his account does not ring true (at least to my ears): he never claimed, for example, that the Etruscan League had managed to act with such united resolve or to excite such fear in Roman hearts.

In my view, we have no real evidence for Sisani’s “stable political-military alliance”, even among the separate ethnicities. It is possible that most or all of the Umbrian nomen (however defined) mustered at Mevania in 308 BC. However, this is hardly evidence for a formal and long-lasting Umbrian League operating in the political-military sphere in the face of the common threat from Rome. Thus, for example, in the opinion of William Harris (referenced below, at p. 101):

-

“Although the Umbrian peoples naturally allied themselves for military purposes [in the pre-Roman period, as they had, for example in 308 BC], there is no evidence worthy of the name that there was an Umbrian League of any importance [that was placed politically] above the individual states.”

Read more:

C.H. Lange, “The Triumph outside the City: Voices of Protest in the Middle Republic”, in:

C.H. Lange and F. J. Vervaet (Eds), “The Roman Republican Triumph: Beyond the Spectacle”, ((2014) Rome, pp. 67-81

P. Camerieri and D. Manconi , “Il ‘Sacello’ di Venere a Spello: dalla Romanizzazione alla Reorganizzazione del Territorio: Spunti di Ricerca ", Rivista di Antichità, 21 (2012) 63-80 S. Sisani, “I Rapporti tra Mevania e Hispellum nel Quadro del Paesaggio Sacro della Valle Umbra”,, in

G. Della Fina (Ed.), “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, (2012) Orvieto (pp. 409-64)

T. Cornell, “Latini’, in:

S. Horbblower et al. (Eds), “The Oxford Classical Dictionary”, (2012) Oxford, at p. 795

M. Spadoni and L. Benedetti, “Perugia Romana (3): La Guerra del 41-40 AC”, Bollettino della Deputazione di Storia Patria per l’Umbria, 109 (2012) 223-70

L. Agostiniani et al. (Eds), “Screhto Est: Lingua e Scrittura degli Antichi Umbri”, (2011) Città di Castello

T. Stek, “Cult Places and Cultural Change in Republican Italy”, (2009) Amsterdam

S. Sisani, “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

J. Scheid, “Rome et les Grands Lieux de Culte d’ Italie”, in:

A. Vigourt et al. (Eds), “Pouvoir et Religion dans le Monde Romain: en Hommage à Jean-Pierre Martin”, (2006) Paris, pp. 75-88

J. Scheid, “Augustus and Roman Religion: Continuity, Conservatism, and Innovation”, in:

K. Galinsky ((Ed.), “Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus”, (2005) New York, pp. 175-93

S. Sisani, “Lucius Falius Tinia: Primo Quattuorviro del Municipio di Hispellum”, Athenaeum, 90.2 (2002) 483-505

F. Coarelli, "Il Rescritto di Spello e il Santuario ‘Etnico’ degli Umbri”, in:

“Umbria Cristiana: dalla Diffusione del Culto al Culto dei Santi,” Atti del XV Congresso Internazionale di Studi sull’ Alto Medioevo, (2001) Spoleto, pp. 39-52

S. Sisani, “Aquilonia: una Nuova Ipotesi di Identificazione”, Eutopia, New series 1-2 (2001) 131-47

F. Coarelli, “Legio Linteata: L’iniziazione Militare nel Sannio”, in

“La Tavola di Agnone nel Contesto Italico, Convegno di Studio, Agnone 13–15 Aprile 1994”, (1996) Florence, pp. 3-16

D. Manconi, P. Camerieri and V. Cruciani, “Hispellum: Pianificazione Urbana e Territoriale”, in:

G. Bonamente and F. Coarelli (Eds),“Assisi e gli Umbri nell' Antichità” Assisi (1996) pp. 375-423; the section on the sanctuary is at pp. 381-92

T. Cornell, “Principes of Tarquinia: Elogia Tarquiniensia ... by Mario Torelli”, Journal of Roman Studies, 68 (1978) 167-73

A. Feruglio et al. (Eds), “Mevania: Da Centro Umbro a Municipio Romano”, (1991) Perugia

W. Harris, “Rome in Etruria and Umbria”, (1971) Oxford

A. Baudrillart, “Coupes Signées de Popilius”, Mélanges de l' École Française de Rome, 9 (1889) 288-98

Ancient History: Pre-Roman Mevania Fonti del Clitunno

Mevania after the Conquest Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia before 41 BC Other Sanctuaries

Mevania after the Perusine War Valetudo and the Magistri Valetudinis

Return to the page on History of Bevagna.