River Clitunno

The source of the river Clitunno (in Latin, Clitumnus) is a spring that emerges from limestone rocks at Campello, to the north of Spoleto. Water from the spring is now channeled under the busy Via Flaminia (behind the trees in the picture) into a lovely shallow lake. (The willows and poplars that surround this lake were brought from the island of St Helena in 1865 in homage to the Emperor Napoleon, who had died there in 1821.)

The lake now feeds a narrow canal that passes the Tempietto del Clitunno (after some 600 m) and then Trevi. It continues to Bevagna, where it merges with the Teverone, becoming the Timia. This river joins the Topino near Cannara, and the combined waters pass Bettona to Torgiano, where they flow into the Tiber. It is important, however, to realise the Clitunno was originally much more important than its current state suggests . It has been diminished over the centuries by a series of seismic events, the first documented example of which occurred in 446 AD. Despite this, it remained prone to flooding and has been the subject of a long series of human interventions that culminated in its almost complete canalisation in the 19th century.

We get a hint of its ancient splendour from an unknown commentator on Virgil’s ‘Georgics,’ (quoted in Latin by Simone Sisani, referenced below, 2012, p. 440, entry 1.12), who noted that:

-

“In Umbria, Clitumnus is a god, and [also] the name of the river that flows into the Tiber” (my translation).

As Simone Sisani commented (at p. 412):

-

“ ... at least for this author, the name of the river applied to a hydrology more extensive than that of today, and included not only the present course of Clitunno [south of Bevagna], but also that of the present Timia [from Bevagna to the Tiber]” (my translation).

He justly observed (at p. 414) that:

-

“The correct reconstruction of the hydrography of the ancient Valle Umbra allows us to understand intuitively the centrality of the river Clitumnus in this territorial context: considering [its entire course from its source at Campello del Clitunno] as far as its confluence with the Tiber, it was undoubtedly the longest river (about 40 km) of the entire [Valle Umbra]. It must also have been much wider than today [based on the testimony of Pliny the Younger, see below]” (my translation).

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 415 and note 34) pointed out that:

-

“In the literary sources, the Clitumnus is always considered the river of Mevania, and its white bulls ... are defined as ‘mevanienses’” (my translation).

It seems likely that the ownership of Mevania originally extended as far as the source: thus, Vibius Sequester included the “Clitumnus mevaniae” in his “De fontibus” (on river sources). However, as discussed below) the source of the river and its lower reaches were transferred to the new colony of Spoletium in ca. 241 BC.

River God Clitumnus

The god Clitumnus featured in the work of two of the great lyrical poets of the 1st century BC:

-

✴Propertius:

-

“I'll go hunting ... where [the god] Clitumnus covers the beautiful stream with his own woods, and his wave bathes the snow-white heifers” (‘Elegies’, 2:19).

-

✴Virgil:

-

"... here are your snowy flocks, Clitumnus and, the noblest sacrifice, your bulls, which, drenched in your sacred stream, have often led Roman triumphs to the gods’ temples" (‘Georgics’, 2:136).

These are among the earliest surviving references of the association of the river with the deity whose name it bore. Thus, the river Clitunno was Clitumnus’ wave (Propertius) or his sacred stream (Virgil). Propertius also referred to Clitumnus’ own woods, which was presumably a sacred grove (see below). As discussed below, Pliny the Younger, who was writing in the 1st century AD, described:

-

“... an ancient and venerable temple, in which is placed the river-god Clitumnus clothed in the usual robe of state; ...” (Letter LXXXVIII to Romanus).

Vibius Sequester, in his “De fluminibus” (list of rivers), which dates to the 4th or 5th century AD, recorded that:

-

“Clitumnus Umbriae, ubi Iuppiter eodem nomine est”

This is our only attestation of the fact that Clitumnus was a manifestation of Jupiter.

In the extracts quoted above, Propertius referred to the snow-white heifers that bathed in Clitumnus’ river, while Virgil referred to Clitumnus’ snowy flocks, which included bulls that were used in sacrifices performed during triumphs held in Rome. The later literary tradition that related to them can be exemplified as follows:

-

✴Silius Italicus, in his description of the aftermath of the Battle of Lake Trasimeno (in 217 BC), referred to:

-

“... Mevania, lying low on the wide plains, [which] breathes forth sluggish mists and feeds mighty bulls for Jupiter's altar” (‘Punica’).

-

✴Statius, speaking of his celebration of the recovery from illness of his friend Rutilius Gallicus, lamented that he would not be able to find an animal fine enough for sacrifice, even if:

-

“... Mevania emptied its valleys [and] Clitumnus supplied its snow-white bulls” (‘Silvae’, 4).

-

✴Juvenal echoed Statius while lamenting the poor quality of the calf that he had sacrificed to Tarpeian Jove in celebration of the safe return from sea of his friend Catullus:

-

“If my personal resources were ample, a match for my feelings, we’d be dragging a bull fatter than Hispulla to the slaughter, .... the product of the fertile fields of Clitumnus” (‘Satires’, 12:1:82).

Sanctuary at the Fonti del Clitunno

Pertica of Spoletium

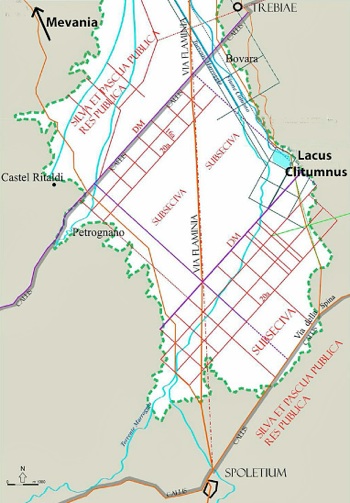

Adapted from Camerieri and Manconi (referenced below, Figure 2)

As noted above, the source and lower reaches of the Clitumnus were transferred to the new colony of Spoletium in ca. 241 BC. This is evident from the work of Paolo Camerieri and Dorica Manconi on the centuriation of Spoletium, summarised in the diagram above, in which the lower reaches of the river are just inside the northeastern boundary of the pertica of the colony. It is also probably reflected in the surviving literary sources:

-

✴while Vibius Sequester (as above) included the “Clitumnus mevaniae” in his “De fontibus” (on river sources), which places the source of the river in the ownership of Mevania;

-

✴Servius, in his commentary on the passage of Virgil’s “Georgics” quoted above, noted that:

-

“Clitumnus et deus et lacus in finibus Spoletinorum” (“Commentary’, 2:146)

-

“Clitumnus, [its] deity and [its] lake are in the territory of Spoletium” (my translation).

This suggests that the sanctuary of Clitumnus at the source of the river also transferred to the new colony.

John Scheid (referenced below, 2006, at pp. 79-80) placed this apparent confiscation in a wider political context:

-

“After the definitive submission [to Rome] of the Latins in 338 BC, three important [Latin] cult sites passed definitively under Roman control:

-

-the federal sanctuary of the Latins on [the Alban Mount] was now a Roman cult site, and the Feriae Latinae were also celebrated at Rome during the federal meetings at the Alban Mount];

-

-the temple of Juno Sospes at Lanuvium [south of Rome] became a common cult site of the Romans and the Lanuvins; and

-

-at Lavinium [near modern Ostia], many annual rites were celebrated by the Lavinates and the magistrates and priests of Rome.

-

Another example is offered by the Umbrian cult site at the source of the Clitumnus ... [which was] manifestly one of the great religious sites of the Valle Umbra. ... Since it was located near Mevania, it seems likely that it was controlled by the Umbrians from Mevania itself or from the surrounding area. When the Latin colony of Spoletium was founded in 241 BC, the cult site clearly passed to it, since it was later found on the boundary of the pertica of Spoletium. ... It was in this way that the Romans used the colony as an intermediary to control the places of memories and of regional reunions of the Valle Umbra” (my translation).

Thus, by analogy, Scheid saw the sanctuary at the Fonti del Clitunno as a communal sanctuary that had long served a a cult site used by the people of the Valle Umbra, which would now also serve the political interests of Rome.

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 415) suggested that:

-

“[The following three characteristics]:

-

-the centrality of the [river Clitumnus, in its original form] in the context of the entire Valle Umbra;

-

-the association of its divinity [i.e. Clitumnus] with Jupiter; and

-

-the association of this divinity with [the ritual of triumphs];

-

... allow us to postulate a close functional analogy between Jupiter/ Clitumnus and, for example, Jupiter Latiaris of the Latin League [centred on the Alban Mount], leaving no doubt about the ethnic relevance of the cult [of Clitumnus at the Fonti del Clitunno] certainly common to all the Umbrian nomen” (my translation).

Tim Cornell (referenced below, at p. 219) gave a useful summary of the key characteristics of the cult of Jupiter Latiaris and the importance of the cult site on the Alban Mount in relation to the Latin nomen:

-

“From the earliest times, the Latins formed a unified and self-conscious ethnic group with a common name (the nomen Latinum), a single language, and a common material culture ... Their shared sense of kinship was expressed in a myth of common ancestry. According to this legend, the Latins traced their origins to a union of Trojan refugees [led by Aeneas] with the native Aborigines, whose king, Latinus, gave his name to the resulting amalgam ... After his death, Latinus was transformed into Jupiter Latiaris and worshipped on the Alban Mount. ... The annual celebration of this cult, known as the ... Feriae Latinae, was an assembly of representatives of all the Latin communities ... each of which contributed items of produce to a banquet: a white heifer was sacrificed and the meat shared among all the participants. ... Participation in the cult was a definition of membership: the Latins were [by definition] those people who received meat at the annual festival ...”

Thus, Simone Sisani made a much wider claim than John Scheid;

-

✴while for Scheid, the sanctuary was a place of “of memories and of regional reunions of the Valle Umbra”;

-

✴for Sisani, participation in the cult at the sanctuary of Clitumnus was the sine qua non for membership of the entire Umbrian nomen (however defined).

We might reasonably ask whether the three characteristics of the sanctuary of Clitumnus enumerated by Sisani (above) really are close enough to the key characteristics of the sanctuary of Jupiter Latiaris to:

-

“ ... leave no doubt about the ethnic relevance of the cult [at the Fonti del Clitunno, which was] certainly common to all the Umbrian nomen.”

Taking them in turn:

-

✴The river Clitumnus, like the Alban Mount, was arguably the most prominent feature in its geographical context. However, in the former case, this context only embraced the people of the Valle Umbra (as discussed further below).

-

✴Vibius Sequester, our only source for the information that Clitumnus was a manifestation of Jupiter, was writing in the 4th century AD. We do not know whether this had been true in the pre-Roman period, or whether it had perhaps been associated with the transfer of the sanctuary to Spoletium.

-

✴Neither Jupiter Latiaris nor Clitumnus can be securely linked to triumphal ritual in the pre-Roman period:

-

•It is true that, on at least four occasions in the early Republic, Roman consuls celebrated triumphs at the sanctuary on the Alban Mount, probably because they had been denied this honour in Rome. However, according to Carsten Hjort Lange (referenced below, at p. 76), this did not represent:

-

“... a revival of an old Latin ritus: [in the pre-Roman period] the Latins, to our knowledge [I think he means ‘as far as we know’ rather than ‘to our certain knowledge’] never celebrated triumphs.”

-

Lange referenced some dissenting scholarship on this point, but it is still fair to say that there is no hard evidence that the Latin nomen celebrated triumphs in the pre-Roman period, whether on Monte Albano or anywhere else.

-

•It is also true that white bulls raised on the banks of the Clitumnus were sacrificed to Jupiter during triumphs in Rome, at least from the late Republic. However (as fas as I know) there is no secure evidence that the Umbrian nomen (however defined) ever celebrated triumphs in the pre-Roman period, whether at the Fonti del Clitunno or anywhere else. (I argue in my page on Valetudo and the Magistri Valetudinis that the via triumphalis recorded in the inscription CIL XI 5041 from Mevania was probably an innovation from the time Augustus rather than a road that followed an ancient triumphal route).

More fundamentally, there is no evidence for an Umbrian nomen that had a shared foundation myth. There was certainly a shared language, for which there is epigraphic evidence across an area far wider than the Valle Umbra (taking in, for example, modern Gubbio, Gualdo Tadino, Colfiorito, Nocera Umbra, Terni, Todi and Amelia). However, I am unaware of any evidence to suggest that Umbrians settled outside the Valle Umbra participated in a shared cult at the Fonti del Clitunno.

In short, in my view, we should probably regard the pre-Roman sanctuary at the Fonti del Clitunno as an important shared cult site of the people of the Valle Umbra, but certainly reserve judgement regarding its wider cultural and political significance.

Sacred Grove of Clitumnus (?)

Two archaic Latin inscriptions (CIL XI 4766) in the Museo Archeologico of Spoleto, which were found in separate locations about 10 km west of the Fonti del Clitunno, bear nearly identical texts:

Honce loucom/ ne qu<i>s uiolatod/ neque exuehito neque

exferto quod louci/ siet neque cedito/ nesei quo die res deina

anua fiet eod die/ quod rei dinai cau[s]a/ [f]iat, sine dolo cedre

[l]icetod, seiquis/ uiolasit Ioue bouid/ piaclum datod

si quis scies/ uiolasit dolo malo/ Iouei bouid piaclum

datod et a(sses) CCC/ moltai suntod

eius piacli/ moltaique dicator[ei]/ exactio est[od]

Michael Gilleland has posted two English translations, one of which is as follows:

-

“Let no-one violate this grove, nor carry away anything that is in the grove, nor set foot in it [or possibly 'cut it'] except annually on the day of the rite; on the day when it is done because of the rite, it shall be permitted to enter (cut) it with impunity. Whosoever violates the grove shall give a purificatory offering of an ox to Jupiter; whoever violates it knowingly and maliciously shall give a purificatory offering of an ox to Jupiter and shall be fined 300 asses [a unit of currency]. The dicator (chief magistrate) shall be responsible for the exaction of the offering and fine”.

The inscriptions record the terms of the so-called lex Spoletina, which governed the use of a wood or grove that was sacred to Jupiter, which was presumably located in the area in which the cippi were found.

In fact, Giuseppe Sordini found the cippi on two separate occasions:

-

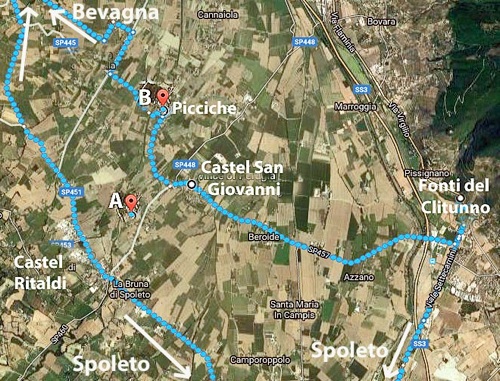

✴Inscription A was found in 1879 on Colle di San Quirico, between Castel San Giovanni and Castel Ritaldi (roughly at A in the aerial view above); and

-

✴Inscription B was found in 1913, embedded in the facade of the church of Santo Stefano in Picciche, marked B above.

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, p. 420) pointed out that Picciche was on a side road that ran from the main Mevania-Spoletium road to the Fonti del Clitunno. He suggested that:

-

“It is likely that [Inscription B] was originally beside this road, alerting travellers to the fact that they were entering an area that was subject to specific religious constraints: [Inscription A] must have had an analogous function, and its find spot near Castel Ritaldi lends credence to the hypothesis that it was beside the main Mevania-Spoletium. road” (my translation).

According to Luca Donnini (in L. Agostiniani, referenced below, entry 75):

-

“Regarding the chronology of the two cippi, based on the script and the language, it certainly seems that both can be securely dated to the years immediately following the deduction of the Latin colony of Spoletium in 241 BC, ...” (my translation)

Suetonius recorded that, in 39 AD, the Emperor Caligula had:

-

“... gone to Mevania, to visit the river Clitumnus and its nemus (sacred grove)” (‘Life of Caligula’, 43).

Simone Sisani (referenced below, 2012, at p. 416) suggested that this was the sacred grove identified by the cippi, and that, until the establishment of the colony at Spoletium, it had belonged to Mevania. He cited his earlier book (referenced below, 2007), in which he had pointed out (at p. 95) that the cippi had been found:

-

“ ... immediately to the west of the Fonti del Clitunno and can indeed be identified as belonging to the sanctuary of Clitumnus, whose identification with Jupiter [recorded by Vibius Sequester, as above] is perfectly consistent with the mention of Jupiter in connection with the [propitiatory fine demanded by the lex Spoletina]” (my translation).

Thus, if Sisani is correct, then Mevania had probably originally owned both the sanctuary at the Fonti del Clitunno and the nearby sacred grove, but both had been transferred to the new colony of Spoletium soon after its deduction in 241 BC.

We can now return to the suggestion of John Scheid (above) that:

-

“... the Romans used the colony [at Spoletium] as an intermediary to control the places of memories and of regional reunions of the Valle Umbra” (my translation).

I wonder whether the lex Spoletina was an example of the Romanisation of the cult of Clitumnus, and whether the association between Clitumnus and Jupiter dates to this period. If so, then the attempt at Romanisation clearly failed: as we have seen, Clitumnus retained at least his Umbrian name and quite probably his Umbrian characteristics for centuries to come.

Transfer to Hispellum (41 BC)

Pliny the Younger, in the letter mentioned above in which he described a visit to the Fonti del Clitunno, noted that:

-

“The Hispellates, to whom Augustus [probably while he was still ‘Octavian’] gave this place, furnish a public bath, and likewise entertain all strangers at their own expense” (Letter LXXXVIII to Romanus).

This information is corroborated in the work of Paolo Camerieri and Dorica Manconi (referenced below, 2010), who identified (at pp. 23-4, Figure 2, as reproduced above, and Figure 3) an ‘anomalous’ parcel of land slightly to the southeast of the Lacus Clitumnus, the centuriation of which was based on the same allotment size (706 meters) as at Hispellum. This suggests that both the sanctuary and the adjacent parcel of newly-centuriated land were transferred from Spoletium to Hispellum at the time of the colonisation of the latter in 41 BC.

This transfer was just one component on a wider programme of colonisation that also included a second important sanctuary: as discussed in my page on the Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia, this sanctuary was transferred from Mevania to Hispellum at this time.

John Scheid (referenced below, 2005, at p. 182) placed these two transfers in the context of Octavian’s policy of religious restoration:

-

“In order that Italy [as well as Rome] benefitted from Octavian’s restorations, he paid attention to old and important Italic sanctuaries. For instance:

-

-he transformed the grove of Feronia (Lucus Feroniae in southern Etruria) and a sanctuary of Fortune (Fanum Fortunae, Umbria) into Roman colonies;

-

-he confirmed the privileges and the autonomy of the sanctuary of of Diana Tifatina (Campania); and, finally

-

-he founded a colony at Hispellum, possibly an old federal sanctuary [at Villa Fidelia], and [also] gave [the new colony] responsibility for the famous sanctuary of Clitumnus.”

John Scheid (referenced below, 2006, at p. 82) expanded on his hypothesis:

-

“It should first be noted that, according to the archaeologists, the large sanctuary at [Villa Fidelia] ... could have succeeded an important supra-regional sanctuary of the Umbrians. [As in other cases], the reason for the foundation of a colony [at the relatively small urban centre here might thus have been] the presence of this renowned Italic supra-regional cult site. Unfortunately, all we know for certain at the moment is that this sanctuary had a supra-regional role in the [4th century AD, as evidenced by the Rescript of Constantine]. ... The place was clearly very important. But, what interests us more particularly was another decision of Octavian, which [was probably] taken in the same context: he gave the famous sanctuary at the source of the Clitumnus to the Hispellates. ... In other words, he confiscated this cult site from Spoletium, which it had owned it since the deduction of the colony [there in 241 BC]; and perhaps he similarly confiscated a supra-regional sanctuary at Villa Fidelia to make a [new] colony and an urban centre” (my translation).

Sanctuary at the Fonti del Clitunno in the 1st Century AD

Pliny the Younger gave a unique insight into the sanctuary here in the 1st century AD:

-

“Have you ever seen the source of the river Clitumnus? If you have not (and I hardly think you can have seen it yet, or you would have told me), go there as soon as possible. I saw it yesterday, and I blame myself for not having seen it sooner. At the foot of a little hill, well wooded with old cypress trees, a spring gushes out, which, breaking up into different and unequal streams, forms itself, after several windings, into a large, broad basin of water, so transparently clear that you may count the shining pebbles, and the little pieces of money thrown into it, as they lie at the bottom. From thence it is carried off not so much by the declivity of the ground as by its own weight and exuberance. A mere stream at its source, immediately, on quitting this, you find it expanded into a broad river ... The banks are well covered with ash and poplar, the shape and colour of the trees being as clearly and distinctly reflected in the stream as if they were actually sunk in it. The water is cold as snow, and as white too. Near it stands an ancient and venerable temple, in which is placed the river-god Clitumnus, clothed in the usual robe of state; and indeed the prophetic oracles [that are] delivered here sufficiently testify the immediate presence of that divinity. Several little chapels are scattered round, dedicated to particular gods, distinguished each by his own peculiar name and form of worship, and some of them, too, presiding over different springs. For, besides the principal spring, which is, as it were, the parent of all the rest, there are several other lesser streams, which, taking their rise from various sources, lose themselves in the river ... every surrounding object will afford you entertainment. You may also amuse yourself with numberless inscriptions upon the pillars and walls, by different persons, celebrating the virtues of the spring and the divinity that presides over it. Many of them you will admire, while some will make you laugh; but I must correct myself when I say so; you are too humane, I know, to laugh upon such an occasion” (Letter LXXXVIII to Romanus).

The key points here seem to me to be the following:

-

✴The ancient temple of Clitumnus, which stood at the point at which the river first emerged from the rock, was surrounded by other temples to lesser gods, most or all of them associated with lesser springs that also fed the river.

-

✴The water here was not apparently valued for its therapeutic value but rather for its exceptional clarity.

-

✴Clitumnus was credited with oracular powers, and the graffiti that amused Pliny presumably attested to his accuracy. John Scheid (referenced below, 1996, at p. 205) interpreted the following passage by Suetonius in this context:

-

“[Caligula] had but one experience with military affairs or war, and then on a sudden impulse; for having gone to Mevania to visit the river Clitumnus and its grove, he was reminded of the necessity of recruiting his bodyguard of Batavians and was seized with the idea of an expedition to Germany”, (‘Life of Caligula’, 43).

-

Scheid suggested that the advice to enhance his German bodyguard might have been offered during Caligula’s consultation with the oracle, Clitumnus:

-

“In this case, the [sudden] decision of the emperor [to depart for Germany in order to recruit more bodyguards] was much less absurd than Suetonius’ description suggests” (my translation).

Read more:

C.H. Lange, “The Triumph outside the City: Voices of Protest in the Middle Republic”, in:

C.H. Lange and F.J. Vervaet (Eds), “The Roman Republican Triumph: Beyond the Spectacle”, ((2014) Rome, pp. 67-81

S. Sisani, “I Rapporti tra Mevania e Hispellum nel Quadro del Paesaggio Sacro della Valle Umbra”,, in

G. Della Fina (Ed.), “Il Fanum Voltumnae e i Santuari Comunitari dell’ Italia Antica”, (2012) Orvieto (pp. 409-64)

L. Agostiniani et al. (Eds), “Screhto Est: Lingua e Scrittura degli Antichi Umbri”, (2011) Città di Castello

P. Cameriere and D. Manconi, “Le Centuriazioni della Valle Umbra da Spoleto a Perugia”, Bollettino di Archeolgic Online, (2010) 15-39

S. Sisani, “Fenomenologia della Conquista: La Romanizzazione dell' Umbria tra il IV sec. a. C. e la Guerra Sociale”, (2007) Rome

J. Scheid, “Rome et les Grands Lieux de Culte d’ Italie”, in:

A. Vigourt et al. (Eds), “Pouvoir et Religion dans le Monde Romain: en Hommage à Jean-Pierre Martin”, (2006) Paris, pp. 75-88

J. Scheid, “Augustus and Roman Religion: Continuity, Conservatism, and Innovation”, in:

K. Galinsky ((Ed.), “Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus”, (2005) New York, pp. 175-93

T. Cornell, “The City-States in Latium”, in:

M. H. Hansen (Ed.), “A Comparative Study of Thirty City-State Cultures: An Investigation Conducted by the Copenhagen Polis Centre”, (2000) Copenhagen, pp. 209-28

D. Manconi, P. Camerieri and V. Cruciani, “Hispellum: Pianificazione Urbana e Territoriale”, in:

G. Bonamente and F. Coarelli (Eds),“Assisi e gli Umbri nell' Antichità” Assisi (1996) pp. 375-423; the section on the sanctuary is at pp. 381-92

J. Scheid, “Pline le Jeune et les Sanctuaires d'Italie: Observations sur les Lettres IV:1, VIII:8 et IX:39”, in:

A. Chastagnol et al. (Eds), “Splendissima civitas - Études d'Histoire Romaine en Hommage à François Jacques”, (1996) Paris, pp. 241-58

Ancient History: Pre-Roman Mevania Fonti del Clitunno

Mevania after the Conquest Sanctuary at Villa Fidelia before 41 BC Other Sanctuaries

Mevania after the Perusine War Valetudo and the Magistri Valetudinis

Return to the page on History of Bevagna.