The first securely documented bishop of Foligno was Urbanus, who attended a synod in Rome in 487 AD. Bishop Fortunatus of Foligno attended another in 502, along with Bishop Boniface of Forum Flaminii and Bishop Florentius of Plestia. However, as discussed below, there is no evidence for a church in the modern city until a much later date, and indeed very little is known about the early history of the diocese:

-

✴There is evidence for an episcopal church at San Valentino di Civitavecchia in the 5th century (see the page on the Early Christianity in Foligno). However, it is not clear whether the bishop who was buried there (as evidenced by an inscription that is now in the crypt of the Duomo) was a bishop of Foligno and/or of Forum Flaminii: San Valentino di Civitavecchia was on Colle San Lorenzo, above Via Flaminia some 6 km northeast of the former and some 3 km southeast of the latter. It continued in use into the Lombard period.

-

✴In the list of securely documented bishops of Foligno compiled by Mario Sensi (referenced below, at pp. 328-30), there are only two such bishops in the 350 years after the synod of 502:

-

•Florus (documented in 679); and

-

•Candidus (documented in 695).

Martyrium of St Felician (ca. 850) ?

The legend of St Felician (BHL 2846-51) recorded that St Felician had been martyred in ca. 250 and buried:

-

“... in Agello ipsius, ubi ipse iusserat, iuxta Fulgineam civitatem supra pontem Caesaris”.

The ‘agellus’ (probably a cemetery) was thus located near civitas Fulginia, above the pons Caesaris (the Ponte di Cesare in modern Via Feliciano Scarpellini), almost certainly near the site of the present Duomo. I argue in my page on St Felician (link above) that Bishop Domenico commissioned this legend from the Abbazia di Farfa in ca. 850, soon after his discovery of the relics, and that he probably also built a martyrium on the later site of the Duomo in which to house them.

In their description of the current Duomo, Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 291, entry 66) began with the observation that:

-

“... hagiographic tradition suggests that [the Duomo] stands on the grave of St Felician. A shrine here cane be hypothesised to have existed at least from the 9th century, evidenced by the re-use of architectural elements from the Carolingian period” (my translation).

These elements comprised the following two objects:

-

-

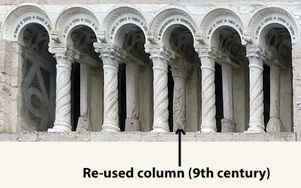

✴According to Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1994, at p. 84), the middle column at the centre of the inner colonnade of the the loggia of the minor facade of the Duomo had been re-used, and:

-

“... could have belonged to the earlier phase of the church” (my translation).

-

Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 291) asserted that it was:

-

“... pertinent to a transenna {a screen around a shrine in early Christian architecture]” (my translation).

-

-

✴According to Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1985, at p. 317), this sculpted fragment (now in the Museo Diocesano) was probably discovered during the restoration of the Duomo in 1903-4 and embedded in a wall of the crypt. Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 291) characterised it as a cornice, and Luigi Sensi (as above) suggested that it had originally formed part of a transenna.

According to Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 129), these constitute the only surviving material evidence for a cult site in Foligno (as opposed to its suburbs) before the 11th century. It is tempting to suggest that both elements came from a shrine in the putative 9th century Duomo that served as the martyrium of St Felician (although we have no proof of that).

In 970, Bishop Theoderic of Metz stole the relics of St Felician and took them to Metz. Sigebert of Gembloux, who carefully recorded this theft (among others) in his “Vita Deoderici, Mettensis Episcopi” (Life of Bishop Theodoric of Metz), described ‘Fulinias’ (sic) as a castrum not far from Spoleto, where the relics were ‘ipso intimo antro’ (in a very deep cavern). There, Bishop Benedetto, who was clearly given no choice in the matter, shed copious tears as the agents of Theodoric helped themselves.

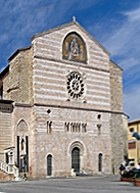

Phases of Construction of the Duomo

First Phase

The first documentary evidence for this church comes in 1078, when Bishop Bonfiglio (1078-1115) made a number of donations to the canons of the ‘Fulginensis ecclesie’, evidenced by a document signed in the ‘domo canonicorum’ (canonica). The goods donated included two mills, one ‘in castro eiusdem ecclesie’ and the other near the pons Caesaris. This is the first time in the archival record that the ‘castrum’ at Foligno is explicitly linked to the Duomo, and it is interesting to note that it was large enough to enclose a mill. Finally, this is the earliest surviving archival record of the cathedral canons and their canonica.

In 1082, the ‘comites’ Gualterius and Odorisius, sons of Ugolini donated to Mainardo, provost Santa Maria Vecchio (on the later site of the Abbazia di Sassovivo) land in a place still called the ‘Agellum’, near which was built the ‘ecclesia et Civita Santi Feliciani’. Thus, by this time, the Duomo stood at the heart of a relatively large walled enclosure that also contained the canonica and, presumably, the bishop’s palace (as well as the mill mentioned above).

Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 129-30) dated the first phase of the construction of the present Duomo to the 11th century. They noted that:

-

“[What survives from this building is], essentially:

-

-the [present] crypt and its oratory, together with the capitals of the columns that have been reused in it; and

-

-probably, some sculptural elements [illustrated as Figures 62 and 63 and preserved in the crypt].

-

The church, in this phase, was already in the form a nave and two aisles, separated by columns, with the presbytery raised above the crypt and terminated in an apse” (my translation).

Second Phase

Cardinal Giulio apparently retained what he (Jacobilli) claimed was the original dedication of the Duomo to St John the Baptist, but added St Felician (at popular request) and St Florentius, confessor and monk. (As explained in the page on St Florentius of Norcia, Jacobilli believed that this saint had died in Foligno in ca. 550 and been buried in the Duomo.) However, the dedication of the Duomo soon settled on St Felician alone.

Third Phase

Renaissance Restoration

A metal cross (1438) that was salvaged from the campanile after the earthquake of 1832 (see below) is dated by inscription and bears the Trinci arms. The same date and the Trinci arms also appear on the main bell in the campanile: it was the date at which Rinaldo Trini was elected as Bishop of Foligno (although Pope Eugenius IV refused to recognise this election). The cross was re-erected on the rebuilt campanile in 1847 (see below). It was removed after the earthquake of 1997 and is now displayed in the room behind the rose window of the minor facade, which forms part of the Museo Capitolare e Diocesano.

Later Work

-

✴A remodelling in 1513 opened up what is now the right transept, so that the building took on its current Latin cross configuration.

-

✴The cupola was added in 1543-8, perhaps at the behest of the papal legate, Cardinal Tiberio Crispo.

-

✴The duomo was badly damaged in the earthquake of 1703, and the area of the apse was remodelled in the period 1720-8.

-

✴The interior took on its present neo-classical appearance after a long programme of restoration in the period 1772-1819.

-

✴The upper part of the campanile was rebuilt in 1847 to a design by Vincenzo Vitali.

-

✴Both facades were "restored" to something like the originals in 1903-4.

Roman Remains

Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below) catalogued the evidence for Roman tombs discovered under or near the Duomo:

-

✴In entry 32, p. 277, they noted that

-

•an unknown number of tombs of an unknown date had been found under the apse during its restoration in 1457; and

-

•other “tombe a tegolini” (tombs covered by terracotta tiles) had been found “on the opposite side” of the apse in 1900.

-

✴In entry 33, p. 277, they noted that other Roman tombs had been found near the main facade in the early 20th century.

They cited a paper by Michele Faloci Pulignani published in 1914, which I have not been able to consult. However, the material presented by Michele Faloci Pulignani in 1934 (referenced below, at pp. 9-10) suggests that the “tombe a tegolini” that were found “on the opposite side” of the apse in 1900 in entry 32 are duplicated in entry 33.

Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1994, pp. 83-5) described four cases of the re-use of Roman elements in the fabric of the Duomo (summarised in Guerrini and Latini, in entries 36-9 respectively):

-

✴According to Luigi Sensi (at p. 83):

-

“The large marble blocks [used for the inscription on the main facade], which are probably derived from recovered material, are perfectly squared and smoothed ...” (my translation).

-

He did not suggest a date for the original working of these blocks, but the position of the corresponding entry 36 in the catalogue of Guerrini and Latini suggests that they assumed a Roman date.

-

✴According to Luigi Sensi (again, at p. 83):

-

“ ... two elements of Roman cornices were inverted to serve as the bases of the arches [of the minor facade]” (my translation).

-

The corresponding entry 37 in the catalogue of Guerrini and Latini specifies the main facade, but I presume that this was an error ??

-

✴According to Luigi Sensi (at p. 84), the capitals the capitals (four Corinthian and the fifth Composite) of the five arches at the front of the loggia of the minor facade:

-

“... were certainly reused, and came from the decoration of a relatively small edifice of the middle Imperial period” (my translation).

-

The corresponding entry 39 in the catalogue of Guerrini and Latini followed this dating, and Sensi cited an earlier source that dated the capitals to ca. 300 AD.

-

✴According to Luigi Sensi (at p. 85), the middle column of the interior of the loggia probably came from the first sanctuary on the site (above). The architrave between this column and the pilaster behind it was formed from a reused marble slab:

-

“We are dealing with a fragment of a Roman statue, with the remains of a left leg, with drapery” ” (my translation).

-

The architrave, which is not easily visible, is illustrated as his Figure 72.

The final Roman remains in the Duomo are:

-

✴a fragmentary inscription (CIL XI 5209), 1st century AD) in the crypt that possibly came from a local sanctuary, discussed by:

-

•Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1985, at pp. 311-2);

-

•Giuliana Galli (referenced below, at pp. 41-2); and

-

•in my page on the Crypt; and

-

✴a marble strigilated sarcophagus (2nd century AD), part of which survives in a small space behind the Cappella della Madonna di Loreto at the base of the campanile, which once housed the presumed relic of St. Messalina (described in the page on St Messalina). [Can the remains of the sarcophagus in the campanile be visited ??]

Read more:

P. Guerrini and F. Latini, “Foligno: Dal Municipium Romano alla Civitas Medievale: Archeologia e Storia di una Città Umbra”, (2012) Spoleto

E. Paoli, “ L' Agiografia Umbra Altomedievale”, in

“Umbria Cristiana: dalla Diffusione del Culto al Culto dei Santi (secc. IV-X): Atti del XV Congresso Internazionale di Studi sull' Alto Medioevo (Spoleto, 23-28 Ottobre 2000)”, Spoleto (2001) pp 479-529

L. Sensi, “Le Testimonianze dell’ Antico”, in

G. Benazzi (Ed.), “Foligno A.d. 1201: La Facciata della Cattedrale di San Feliciano”, (1994) Foligno, pp. 81-7

M. Sensi, “Visite Pastorali della Diocesi di Foligno: Repertorio Ragionato”, (1991) Foligno

The list of bishops (at pp. 328-30) mentioned above is available on-line in the website of the Centro Studi Federico Frezzi.

L. Sensi, “La Raccolta Archeologica della Cattedrale di Foligno”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 9 (1985) 305-26

M. Faloci Pulignani, “Il Corpo e le Reliquie in San Feliciano Martire, Vescovo di Foligno (1934), republished in:

G. Bertini and M. Sensi (Eds), “San Feliciano, Cattedrale di Foligno”, (2004) Foligno

L. Jacobilli, “Vite de' Santi e Beati di Foligno”, (1628)

Proceed to the Main Facade.

Return to the Monuments of Foligno.

Return to Walk I.