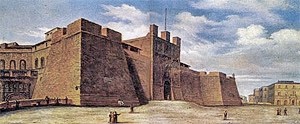

Facade of Rocca Paolina (after the filling in of the moat in ca. 1800)

Panel (19th century) Giuseppe Rossi, Galleria Nazionale

Salt War (1540)

The history of this fortress begins in 1534 when Ridolfo Baglioni took Perugia, murdered the papal legate, Cinzio Filonardi and burned down the legatine residence (the ex-Palazzo del Podestà). When papal forces re-took the city in 1535, the new legate Marino Grimani exiled the Baglioni and confiscated their property. He established his residence in the palace that had belonged to Gentile Baglioni, and began its fortification.

The Perugians invited Ridolfo Baglioni back to the city in 1540 in a rebellion that was brought to a head by the imposition of a tax on salt, which was subsequently known as the Salt War. Pier Luigi Farnese, the natural son of Pope Paul III and Captain General of the papal army, marched into Perugia at the head of 12,000 troops (mainly Swiss mercenaries). He crushed the city's rebellion and ended the Baglioni hegemony.

Farnese Palace and Fortezza di San Cataldo (1540)

Pier Luigi Farnese commissioned Antonio da Sangallo the Younger to design a huge palace incorporating the Baglioni palaces. It was carefully integrated into the existing urban environment, notwithstanding the fact that it entailed some demolition:

-

✴its west facade, on the site of the palace of Grifone and Malatesta Baglioni, opened onto the Piazza di Santa Maria dei Servi, the site of the important church of Santa Maria dei Servi; (below); and

-

✴its east facade, on the site of the palace of Gentile Baglioni, respected the surviving remains of the Etruscan city walls, and incorporated Porta Marzia (see below) as its main portal.

This palace was linked by a fortified corridor to a new fortress, the Fortezza di San Cataldo, which was to act as a safe haven for the inhabitants of the new palace, in the way that the Castello di Sant' Angelo served the residents of the Palazzo Vaticano, Rome.

The palace was linked by a fortified corridor to a new fortress, the Fortezza di San Cataldo. which was so-named because it incorporated the church of San Cataldo. It also incorporated the nunnery of Santa Maria delle Vergini and threatened to engulf that of Santa Giuliana. The fortress was to act as a safe haven for the inhabitants of the new palace, in the way that the Castello di Sant' Angelo was used for the residents of the Palazzo Vaticano, Rome.

The foundation stone of the new palace was laid in November 1540. It seems likely that Pier Luigi Farnese intended it for his own use, but his attention soon moved to the more prestigious possibilities of Parma and Piacenza. His son, Ottavio Farnese, whom Paul III initially intended that should rule Perugia as "Perpetual Captain", visited the site in March 1541, and was apparently content.

The palace was largely complete by September 1541, when Paul III visited Perugia. However, he is reported to have said: "Questo non basta: voglio che vi si faccia una fortezza" (This is not enough: I want you to build a fortress). Whether or not this is true, it is certain that this change in design was subsequently made. It could have occurred after the assassination of Pier Luigi Farnese, which led to the elevation of Ottavio Farnese as Duke of Parma and Piacenza and hence his loss of interest in Perugia.

In 1547, when the papal legate Tiberio Crispo widened what is now Via Mazzini (see Walk I), he reused two pieces of sculpture from the palace to adorn it:

-

✴the arms of Paul III, which he placed at the junction with what is now Corso Vannucci; and

-

✴the head of a horse, , which he placed at the junction with what is now Piazza Matteotti.

Rocca Paolina (1542-7)

Under the new plan, the palace walls were replaced by the forbidding curtain walls of Rocca Paolina, complete with a moat. The original nine entrances were replaced by a single entrance to the north, which was protected by a drawbridge. The design of the Fortezza di San Cataldo was correspondingly reduced in scope: a fortunate consequence was that the church and nunnery of Santa Giuliana were spared.

The new project required the demolition of Santa Maria dei Servi. Part of the adjoining convent survived:

-

✴part of it provided accommodation for the students of Sapienza Nuova, whose original premises next to the church of Santa Maria dei Servi were also demolished;

-

✴and part of it (now known as Casa Moretti-Caselli) provided accommodation for the students of Sapienza Bartolina from 1571.

(These colleges are described in the the page on the Sapienze (Colleges) of Perugia.

Other casualties of the project included:

-

✴Porta Marzia (see below);

-

✴Santa Lucia di Colle Landone (on the later site of Palazzo Donini);

-

✴the churches of San Savino and San Cataldo, the dedications of which passed to SS Savino e Cataldo; and

-

✴two structures that were demolished to allow a clear field of fire from the fortress:

-

•the upper part of the campanile of San Domenico; and

-

•the upper church of of Sant’ Ercolano.

The construction project was taken over by Galeazzo Alessi, who arrived in his native Perugia in the train of the new papal legate, Ascanio Parisani. The people of Perugia were forced to work on the construction of the new fortress and to pay for it, albeit that Cardinal Parisani managed to persuade Paul III to halve the levy imposed on them for the purpose.

Complex from the east Complex from the south

Panels (19th century) by Giuseppe Rossi, Galleria Nazionale

Four panels (19th century) by Giuseppe Rossi (now in the Galleria Nazionale, two here, one above and one below) depict the structure after the moat had been filled in but before its demolition:

-

✴The main body of the Rocca occupied most of the square defined by today’s Piazza Italia, Corso Vannucci, Giardino Carducci, and Via Marzia (where part of Porta Marzia was reassembled in the fortress wall).

-

✴The southern stronghold occupied most of the square defined by today’s Via Marconi, Via Massi and the north part of Via Fanti.

Once the fortified structure was in place, work began on the internal buildings, including a palace for the papal legate. Galeazzo Alessi completed this phase of the work in the 1547.

Frescoes in Rocca Paolina (1543-4)

Giorgio Vasari reports that Lattanzio Pagani began the decoration of the newly built Rocca Paolina. Cristofano Gherardi, il Doceno (who was a close associate of Vasari) “not only assisted ... Lattanzio, but afterwards executed with his own hand the greater part of the best works that are painted in the apartments of that fortress, in which there also worked Raffaellino del Colle and Adone [Dono] Doni of Assisi, an able and well-practised painter .... Tommaso [Bernabei, il] Papacello also worked there ...”

This is the only surviving record of the commissioning of the frescoes of Rocca Paolina. It is unsurprising that the team included no Perugian artists: indeed, apart from Dono Doni, all the artists came from outside Umbria. Unfortunately, all of their work here was lost when the fortress was demolished in 1860.

Vasari is explicit the work had been commissioned by “Messer Tiberio Crispo, who was governor and castellan at that time”. A number of considerations suggest that the time in question was 1543-4:

-

✴Serafino Siepi, who described the surviving and frescoes in his guide of 1822, says that those in the chapel (which he attributed to Dono Doni) were dated by inscription to 1543;

-

✴Giorgio Vasari says that he called Cristofano Gherardi from Perugia to Rome in 1543, where he stayed for “many months”;

-

✴Raffaellino del Colle is documented in Perugia in June 1544;

-

✴Tiberio Crispo became a cardinal in December 1544, after which the title “Messer” would have been inappropriate; and

-

✴Giorgio Vasari called Cristofano Gherardi and Raffaellino del Colle (whom he describes as his “friends and pupils”) to Naples in 1545, albeit that Cristofano was too ill to respond.

If this is correct, Vasari’s reference to Tiberio Crispo as “governor and castellan” was either incorrect or perhaps was a reference to Tiberio Crispo’s position at Castel Sant’ Angelo, Rome in 1542-5. He energetically promoted the decoration of the Roman fortress during his tenure, and might also have had responsibilities at Rocca Paolina before his appointment as Cardinal Legate of Perugia (1545-8).

Destruction (1798-1860)

When Napoleon’s army invaded Italy in February 1797, the Perugians rebelled against the papal authorities. They removed the inscriptions and papal arms from the walls of the Rocca and threw the statue of Pope Paul III into the moat. This occupation ended after only a month with the signing of the Treaty of Tolentino (1797).

The Rocca was probably left largely undisturbed during the second French occupation of Perugia in 1798-9 (when Perugia formed part of the Roman Republic).

The Rocca was probably left largely undisturbed again during the third French occupation of Perugia in 1808-14 (when the papal States were formally annexed to France and Perugia formed part of the Dipartimento del Trasimeno).

With the fall of Napoleon in 1814, Perugia was once more under papal control. When Pope Pius IX was driven from Rome in 1848, the democratic government of Perugia decided (on 11 December) to demolish the fortress. The honour of wielding the first hammer blow was given to Count Benedetto Baglioni. When manual means failed, mines were used, but substantial parts of the fortress remained in tact. These efforts however had the unintended consequence that the vestiges of the Baglioni houses within of the fortress were finally destroyed. However, much of the fortified fabric seems to have survived.

Papal troops retook Perugia in June 1849 and the captain of the papal guard, Costantino Forti was sent to the city with orders to restore the fortress.

In September 1860, when Piedmontese forces under the command of Maurizio Gerbaix de Sonnaz reached Porta di Sant’ Antonio and Porta Santa Margherita, the defending papal forces under Antonio Schmidt d' Altorf took refuge in the Rocca. General Manfredo Fanti sent reinforcements, who stormed through Porta San Pietro and ranged their heavy guns on the Rocca. General Fanti arrived in person soon after in order to accept Schmidt’s capitulation.

Marchese Gioacchino Napoleone Pepoli, who took office two days later as Commissario Generale Straordinario delle Provincie dell’Umbria, signed a decree (15th October) that gave the Rocca to the city. Perugia was formally incorporated into the Kingdom of Italy after the plebiscite of 5th November, 1860 and the city authorities duly authorised the demolition of the Rocca on 17th December.

Excavation (1930 - 65)

Excavation began in 1931 but only really progressed in 1963, under the direction of Ottorino Gurrieri. The excavations were finally opened to the public in 1965. The escalator to Piazza dei Partignani opened in 1983.

Return to Monuments of Perugia.

Return to Walk II (Etruscan walls and Porta Marzia); or

Walk VII (which includes walks around: the excavations of some of the buildings that were demolished to make way for the fortress; the surviving remnants of it; and the urban redevelopment after its demolition).