The Duomo is formally part of the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo, and entrance is by ticket only, purchased from the Tourist Office. Access is included in the price of a “Carta Unica”, which is also available there.

History

The Duomo, which was built in the period 1290-1310, has a rectangular nave and originally had a semi-circular apse.

-

✴Two colonnades of six columns divide the nave from the aisles.

-

✴The first bay of the nave can be regarded as a transept, although it does not extend beyond the sidewalls: it is higher than the side aisles and is vaulted (unlike the rest of the nave).

-

✴There are five shallow semi-circular side chapels on each wall of the nave.

The plan is characterised by a lack of symmetry: for example, the side chapels are not centrally placed in their respective bays. This was probably because the plan had to conform to constraints imposed by the site.

The plan was subsequently augmented:

-

✴Lorenzo Maitani demolished the original apse and built the present rectangular tribune in 1328.

-

✴The Cappella del Corporale was built as an extension to the left transept in 1350-6.

-

✴The Cappella Nuova was built as an extension to the right transept in 1406-25, after the demolition of the old sacristy and a side chapel there.

Tribune (1328)

Crucifix (ca. 1320)

The wooden Crucifix behind the high altar is attributed to Lorenzo Maitani.

Stained Glass (1334)

Giovanni di Bonino of Assisi received a payment in 1334 “pro complimento fenestre vitri maioris tribune dicte ecclesie" (i.e. for completing the magnificent stained glass window of the tribune). This window must have been installed after January 1335, when the old apse was demolished. It contains scenes from the life of Christ, which alternate with figures of prophets, doctors of the church and the Evangelists.

Choir Stalls (1330-70)

A group of Sienese artists carved the wooden choir stalls, which then stood in the first bay of the nave. This was one of the earliest marquetry structures of its type, although documents record numerous additions and restorations in the 15th century. In 1536, Pope Paul III paid for it to be moved to the apse so that the congregation in the nave could participate more directly when Mass was celebrated at the high altar. This move marked the beginning of the 16th century remodelling of the interior.

The structure restored in 1859, when many of its components were transferred to the Museo dell’ Opera del Duomo (see below) and replaced in the tribune by copies. These copies include the large triangular marquetry panel (ca. 1370) of the Coronation of the Virgin with a choir of musical angels from the centre (again, see below for the original).

Frescoes (1370-84)

Left wall Back wall

This fresco cycle, which covers the three walls and the vaults of the tribune, was one of the most important in Italy at the time it was commissioned. Ugolino di Prete Ilario led a team of local painters that included: Cola Petruccioli; Andrea di Giovanni; and Francesco di Antonio. (Many of the frescoes on the right wall were repainted in the late 15th century - see below).

Cola Petruccioli, Andrea di Giovanni and Francesco di Antonio are documented in relation to the frescoes of the fictive choir (1380) that were obscured when real choir stalls were moved here from the nave in 1536. These frescoes, of which the upper part can still be seen (as in the photograph above), depicted the canons seated in choir stalls.

Renaissance Restoration

Restoration by il Pastura Right wall Restoration by Pintoricchio

1497-9 details of which are to the sides here 1492-6

Some of the frescoes on the right wall were restored at the end of the 15th century:

-

✴Jacopo Ripanda da Bologna is documented in 1485-95 at work on the frescoes of the “balcone" (balcony) of the choir. His workshop here included:

-

•Antonio del Massaro da Viterbo, il Pastura, in 1489-92; and

-

•Giovanni Francesco d' Avanzarano, il Fantastico, in 1490.

-

✴Pintoricchio was commissioned to repaint some of the frescoes in June 1492. Pressure on him to start work led to a testy letter in that year to the Opera del Duomo from Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere (the future Pope Julius II), insisting that they exercise patience until Pintoricchio had completed work in the cardinal’s Roman palace. The required repainting involved the figures of SS John and Mark and SS Jerome and Ambrose to the sides of the rose window of the right wall, which were the pendants to SS Matthew and Luke and SS Gregory and Augustine on the opposite wall. Pintoricchio had only completed the two Evangelists by late 1492, when Pope Alexander VI called him to Rome to begin work on the Borgia Apartments of the Vatican Palace. Alexander VI wrote to the Opera del Duomo in 1493, asking them to wait for Pintoricchio’s return until the work in the Vatican was finished. Pintoricchio finally returned to Orvieto in March 1496 to work on the last two frescoes. He must have subsequently made only sporadic appearances because, when he left Orvieto for the last time a year later, financial guarantees of completion that he had provided were called in. Only two of the four frescoes (illustrated above) that Pintoricchio and his workshop repainted survive:

-

•St Mark writing his Gospel; and

-

•St Ambrose in his study.

-

✴Antonio da Viterbo, il Pastura repainted the four scenes at the lower left in 1497-9:

-

•the flight to Egypt (destroyed);

-

•the Presentation of Christ at the Temple, which is set in front of a representation of the Duomo;

-

•the Annunciation; and

-

•the Visitation.

Transepts

Little of the original painted decoration of the transepts survives. However, some important sculpture that formed part of the 16th century remodelling survives here, despite the remodelling of ca. 1890.

Pietà and St Gregory (ca. 1480)

The fresco was painted so that light from the rose window in the transept would illuminate the flesh of the dead Christ. St Gregory is depicted to the right. This is a reference to a legend first recorded in the 15th century in which Pope Gregory I had a vision of the dead Christ and the instruments of the Passion while saying Mass. This vision was taken to illustrate the dogma of transubstantiation.

Cappella dei Magi (1514-46)

This chapel to the right of the tribune was ceded to the Monaldeschi della Vipera (or della Sala) in the early 15th century, when their original chapel was demolished to make way for the Cappella Nuova. After the death of Pietro Antonio Monaldeschi della Vipera in ca. 1500, it became the responsibility of his widow, Giovanna Monaldeschi della Cervara. (The marriage of these cousins in 1467 had ended the internecine strife between the Monaldeschi factions).

Giovanna Monaldeschi made a donation for a new altar for the chapel in 1502, and her will of 1509 contained a second donation for its decoration. Michele Sanmicheli, who became capomaestro that year, demolished the earlier chapel and began its reconstruction in 1514.

Giovanna seems to have commissioned a tomb in the chapel for her husband, in which she also wished to be buried. The inscription survives to the right (on the entrance wall to the Cappella Nuova). It records that she “made it” (presumably the tomb) in 1516 for her esteemed husband and herself. The encomium to Pietro Antonio translates: “His father having been exiled by tyranny, he nevertheless conducted himself with equanimity and care for the republic ... with such integrity and faith that no one surpassed him in public charity”. When Giovanna died in 1518, the responsibility for the decoration of the chapel passed to the Opera del Duomo.

Antonio da Sangallo arranged for Simone Mosca to take over the project in 1535. According the Giorgio Vasari, “there was summoned, at the suggestion of Simone, his very dear friend Raffaello da Montelupo” to work on the central relief under the arch. A document records that Simone Mosca acted as host to Antonio da Sangallo when he made a short visit in 1536 to introduce Raffaello da Montelupo to the authorities.

According to Giorgio Vasari, Francesco Mosca, il Moschino subsequently executed the group of angels in the upper part of the central relief, the relief of God the Father in the pediment, the angels in the lunette and the Victories to the sides of it. The chapel itself was finally completed in 1546.

Cappella della Visitazione (1547-54)

Giorgio Vasari recorded that, when the Cappella dei Magi was completed, the Opera del Duomo commissioned Simone Mosca build its pendant, “on the understanding that the figures should be varied without varying the architecture”. In fact, the design is usually attributed to Simone Mosca and Raffaello da Montelupo.

Vasari added that the relief of the Visitation at its centre was commissioned from Simone’s son, Francesco Mosca, il Moschino. The young Ippolito Scalza seems to have worked as an assistant on the project.

In the central relief, the meeting between the Virgin and St Elizabeth prior to the birth of their respective sons is set among buildings that are sketched in deep perspective. Francesco Mosca must have been very proud of this work, because he suggested that the Opera del Duomo should take advice from Michelangelo as to it value. In the event, this suggestion does not seem to have been taken up.

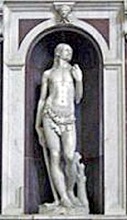

Risen Christ (ca. 1550) and the Virgin (1580-2)

Risen Christ Virgin

Raffaelo da Montelupo (attr.) Fabiano Toti

These figures are in the niches that flank the entrance to the Cappella del Corporale. The niche on the right was built in the 1550s and that on the left some ten years later.

-

✴The figure of the Risen Christ, which is attributed to Raffaello da Montelupo, was probably inspired by the Risen Christ (1518-20) by Michelangelo in Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome. It had a variety of locations until 1559, when it was placed in the earlier of these two niches.

-

✴The figure of the Virgin by Fabiano Toti was originally placed in the later of these two niches.

These figures subsequently changed places, probably in ca. 1593. (More detail is given in the page on the 16th century remodelling).

Adam (16th century) and Eve (1560s ?)

Adam Eve

Fabiano Toti Raffaelo da Montelupo (attr.)

These figures are in niches that flank the entrance to the Cappella Nuova. The niches were built as pendants to those on the opposite wall (see above); the niche on the left was built in ca. 1557 and that on the right some ten years later.

-

✴The niche on the left was built originally to house a figure (1556) of St Sebastian by Ippolito Scalza. This figure is was moved to the counter-facade in ca. 1593 and is now in the Museo dell' Opera del Duomo. The figure of Adam by Fabiano Toti replaced it.

-

✴The figure of Eve was documented in its current location (the niche on the right) in 1584, when it was attributed to Raffaelo da Montelupo.

Pietà (1570-9)

-

✴the Pietà (1499), which was conceived for an altar in the funerary chapel of Cardinal Jean Bilherès in Santa Petronilla, Rome and is now in St Peter’s, Rome; and

-

✴the Pietà (ca. 1550), which was probably intended for Michelangelo's own funerary monument and which is now in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence.

The commission was given to Raffaello da Montelupo, but by the time that the marble for the work arrived in Orvieto (in 1570), he was dead. The commission therefore passed to his successor, Ippolito Scalza.

The group comprises the dead Christ and Madonna with St Mary Magdalene and Nicodemus. It is carved from a single block of marble (except for the left arm of Nicodemus and the upper part of the ladder that he is holding). Scalza signed the base of the completed work in 1579.

Unlike the earlier works by Michelangelo, the Orvieto Pietà was commissioned with no particular function and no specific location in mind. Given the Eucharistic significance of the work, it is surprising that it was never incorporated into the iconographical programme of the body of the church. It was instead "provisionally" installed in front of the fresco of the Pietà by Luca Signorelli in the Cappellina dei Corpi Santi of the Cappella Nuova.

The sculpture immediately became the main object of devotion in the chapel, and over-shadowed Signorelli's frescoes there. Scalza wrote to the Opera del Duomo in 1588 pleading for a more appropriate location to be found, not least because the work was vulnerable to damage. This plea went unheeded, and the chapel had to be locked in 1590 to ensure that the sculpture was not damaged. In 1609 (during the debate about the location of the figures of the Annunciation by Francesco Mochi), it was decided that it should be placed in front of the tabernacle on the high altar, but this plan was never put into effect. The group remained in the Cappella Nuova until early in the 20th century, when it was moved to its current location.

Organ (1580-8)

Figures of Christ (1608 and 1628)

Christ at the Column (1628) Ecce Homo (1608)

Ecce Homo (1608)

This marble figure, which was Ippolito Scalza’s last work, stands in front of the pilaster at the junction of the arch of the tribune with the right transept of the Duomo. Light from the rose window in the transept illuminates the superbly finished marble.

Christ at the Column (1628)

This marble figure by Gabriele Mercanti, which stands in front of the pilaster at the junction of the arch of the tribune with the left transept, was conceived as a pendant to the Ecce Homo.

Nave

The evolving style of the magnificent capitals (1290 - 1310) of the pillars of the nave have allowed the phases of the construction of the Duomo to be ascertained (as described on the introductory page):

-

✴The capitals in the crossing were almost certainly the first to be carved.

-

✴The capitals of the three pairs of columns nearest the tribune probably belong to a distinct second phase that ended in ca. 1300.

-

✴A document of 1310 records that work was about to begin on the wooden roof of the nave and on the exterior facade of the church. The capitals of last two pairs of columns is close to that of the (slightly later) reliefs on the façade. These columns probably belonged to this final phase of construction that ended in ca. 1310.

Original Decoration

As noted above, the capitals of two pairs of columns nearest to the facade probably dates to ca. 1310. The capital of the 2nd column on the left is distinguished by an inscription in Latin of the first lines of the “Ave Maria”. The design of all four capitals has been attributed to Ramo di Paganello.

Renaissance Decoration

Pope Martin V, after a visit to Orvieto in 1420, restored the Opera del Duomo to secular (as opposed to clerical) administration and reformed its statutes, and this gave impetus for the programme of redecoration of the Duomo. Two important works are known to have been commissioned for the nave:

-

✴In 1421, Donatello was invited to sculpt a bronze figure of St John the Baptist, which was to be mounted on the baptismal font (1390-1403) on the left. It is unclear whether this invitation was ever accepted.

-

✴In 1425, Gentile da Fabriano was commissioned to paint a fresco of the Maestà on the left wall (see below).

Stoup (ca. 1456) Stoup (1486)

There are two Renaissance stoups for holy water in the nave:

-

✴The stoup (ca. 1456) to the right in the entrance bay, is usually considered to be an autograph work of Antonio Federighi (died 1483). This work is sometimes dated to 1484, because a document of that date laments the lack of a beautiful stoup for holy water. The earlier dating of ca. 1456 is made on stylistic grounds: it might be that this stoup was in a private chapel by 1484 and hence the need for a new one for the nave. (The figure of St John the Baptist that now stands on this stoup was probably a separate commission).

-

✴Payments for a new stoup were made in 1486 to another two Sienese sculptors: Francesco di Leonardo d’ Antonio; and Giovanni di Stefano. A related payment was made to Jacopo Ripanda da Bologna for gold foil for its decoration. These payments probably relate to the stoup that is now near the left wall, which preserves traces of original gilding.

Post-Tridentine Changes

Pope Paul III commissioned a design from Antonio da Sangallo il Giovane for a new ceiling for the nave. The design survives in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. Work on the ceiling began in 1538-40, but it was subsequently abandoned.

Frescoes in the Nave

Most of the votive frescoes in the nave were covered by stucco decoration during the 16th century remodelling of the Duomo. A notable exception was the important fresco (1425) of the Maestà by Gentile da Fabriano, although this was cut down, modified by the addition of an extra figure and inserted into a stucco tabernacle (see below). A number of other frescoes were recovered during a major restoration in 1890.

Madonna and Child enthroned (1425)

Before restoration of 1984-9 After restoration of 1984-9

As noted above, this fresco by Gentile da Fabriano on the left wall was one of the first works commissioned by the Opera del Duomo after the renewal of its autonomy and the publication of its first formal statutes in 1421. Gentile arrived in Orvieto in August 1425 and was paid for the completed work two months later. The Opera del Duomo insisted that the Alberici family remove coats of arms that they had commissioned below the fresco, in order to underline their direct control of the decoration of the Duomo and their responsibility for the commissioning of this important component of it.

The image was highly venerated, and it was probably for this reason that it was one of the few frescoes in the church that was not covered in the 16th century remodelling of the interior. Instead, it was enclosed in a stucco tabernacle that was incorporated into the new unified decorative scheme in 1568. A figure of St Catherine was added to the right, in order to bring the fresco and its new tabernacle into the centre of its bay. The tabernacle was removed in the late 19th century and replaced by a fictive mosaic surround (illustrated above). The figure of St Catherine was removed in the restoration of 1984-9, and the original figure of a transparent angel was found underneath.

As restored, the fresco depicts the Madonna and Child enthroned. The Child is trying to clamber off the Madonna's lap, His arm raised in blessing. Much of the original modelling of the figures (particularly of the Madonna’s robes) has been lost. The work is nevertheless of exceptional quality.

First Chapel on the Right

-

✴St Sebastian; and

-

✴the Madonna and Child enthroned, which is attributed to Pietro di Nicola Baroni and dated by inscription to 1474.

Second Chapel on the Right

Third Chapel on the Right

-

✴a figure of St John the Evangelist from what was a Crucifixion; and

-

✴St John the Baptist as a hermit.

Fourth Chapel on the Right

-

✴an orant female saint (illustrated here); and

-

✴(to the right) an intriguing fragment of the hand of Christ in a quarter-circle that seems to have been at the top left hand corner of a fresco. (This device was used in another fresco (13th century) in San Giovenale that depicted the conversion of St Paul).

First Chapel on the Left

Details from the frescoes above

This chapel contains some lovely fresco fragments (14th century) that are attributed to Cola Petruccioli. The faces of St Helena (to the left) and the Virgin are particularly fine.

Second Chapel on the Left

-

✴St George on horseback;

-

✴part of a Crucifixion; and

-

✴a bishop with an open book.

Art from the Church

Fragments of the Choir Stalls (1330-70)

As mentioned above, the choir stalls were restored in 1859, when many of its components were transferred to the Museo dell' Opera del Duomo and replaced in the tribune by copies.

The largest surviving fragments are:

-

✴the pulpit and lectern (ca. 1330)

-

Marquetry figures of the Apostles adorn the revolving pulpit. The lectern incorporated into it has a semi-circular indentation on its lower edge to allow the ribbon of what must have been a huge Bible to hang vertically.

-

✴figures of the Annunciation (ca. 1350)

-

These initially polychrome figures were moved from the choir when it was moved from the nave to the apse in 1536.

-

✴the panel of the Coronation of the Virgin (ca. 1370)

-

This large triangular marquetry tympanum came from the centre of the choir screen. The depiction of the Coronation of the Virgin with a choir of musical angels is achieved solely by relying on the different grains of small wooden tesserae. This composition was intended to replicate the mosaic planned (but not executed) for the central tympanum of the facade. It therefore gives an important indication of how this tympanum was originally conceived.

Madonna and Child with angels (ca. 1347)

Christ and Angels (1347-8)

These figures came from an altar in the left of the nave of the Duomo that might have housed the Sacro Corporale while the Cappella del Corporale was in construction. They were moved from the Duomo to the plinths in the exterior lunette of the Porta del Corporale in 1890, and the angels were subsequently badly damaged. They were removed from this location in 1985 and are now in the Museo dell' Opera del Duomo.

-

✴The figure of Christ is attributed to Nino Pisano. He is seated and holds a chalice in His right hand: the wafer that was originally in His left hand has been lost.

-

✴The two angels (both of which have been damaged) were probably those that were made from the marble that Andrea Pisano (see above) sent to the Duomo in ca. 1347. They are of inferior quality and are attributed to Tommaso Pisano.

St Sabinus Altarpiece (1473)

The altarpiece, which is dated by inscription, was documented in the Oratorio di San Savino in Palazzo Carvajal (which was then called Palazzo Pietrangeli) in 1829, and was first attributed to Giovanni Boccati in 1866. A document in the archives of Orvieto records that Antonio Simoncelli made a payment to Giovanni Boccati in 1473, and this almost certainly relates to this altarpiece.

The altarpiece was placed on the art market in Florence in 1895.

-

✴The main panel and the original frame (minus the predella panel) were sold to the Szpmvszeti Muzeum (Museum of Fine Arts), Budapest.

-

•The panel itself depicts the Madonna and Child enthroned, with SS Juvenal, Sabinus of Canosa, Augustine and Jerome, against a gold background. There are two standing angels on each side of the Madonna, and two sit on the marble pavement at her feet, playing stringed instruments. The face of the Madonna seems to have been repainted later in the 15th century, perhaps by Antonio del Massaro da Viterbo, il Pastura.

-

•The upper cornice of the frame contains three painted angels with garlands, and there is a figure of Christ the Redeemer in the lunette above.

-

✴The predella panels depict four scenes from the life of St Sabinus:

-

•St Sabinus talking to his friend, St Benedict on Monte Cassino about Totila's entry into Rome (now in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid);

-

•St Sabinus recognises Totilla (once in the Mario Lanfranchi collection, Rome);

-

•the Archdeacon Vindemius attempts to poison St Sabinus (now in the Galleria Nazionale, Urbino); and

-

•death of St Sabinus (once in the Spiridon collection, Paris).

There is some confusion as to the original location of the altarpiece:

-

✴Some sources indicate that it came a chapel in the Duomo that was dedicated to St Sabinus of Canosa, but there is no record that any such chapel ever existed.

-

✴More recent scholars suggest that it was painted for the Oratorio di San Savino in Palazzo Carvajal. Cardinal Girolamo Simoncelli, the son of Antonio Simoncelli, built the palace in 1548, and Caravajal dei Caravajal-Simoncelli built the oratory in 1571. It is possible that an earlier palace and oratory on this site belonged to the Simoncelli family at the time that the altarpiece was commissioned.

-

✴A more likely candidate for its original location seems to me to be San Giovenale, near Palazzo Carvajal, given that:

-

•the altarpieces features St Juvenal as well as St Sabinus;

-

•San Giovenale contained relics of St Sabinus and was documented as SS Giovenale e Sabino in 1314; and

-

•St Sabinus features in a number of other works in the church; and

-

•one of the above is a second altarpiece (ca. 1490) with the Madonna and Child enthroned an SS Juvenal, Sabinus of Canosa, with three scenes from the life of St Juvenal in its predella .

-

It is possible that Antonio Simoncelli commissioned the altarpiece for the church, and that it reverted to his descendants before 1807, when Palazzo Carvajal was sold to the Pietrangeli family.

Madonna and Child (late 15th century)

It seems unlikely that the present ornate frame was originally used for the panel: its depth suggests that it originally housed a sculpted relief. Its pinnacle is adorned with small sculptures in the round that depict the risen Christ flanked by half figures bearing symbols of the Passion. Its recent restoration has revealed that it was originally the central compartment of a polyptych, the other parts of which no longer survive.

The framed panel is now housed in an elegant gilded wooden tabernacle that has a fragmentary inscription on the bottom. This commemorates Baldassarre Leonardellii, the treasurer of the Opera del Duomo, and his wife Felice. His will (1484) refers to a chapel, the Cappella dei Ogni Santi, which he had built in the right transept.