Ippolito Scalza, who was born in Orvieto, probably began work in the Duomo in ca. 1550. He was first documented in 1555, when he was at work on the figures of prophets on the facade under Francesco Mosca, il Moschino (see below). (His cousin Ludovico Scalza was also part of this team). He became an accomplished architect and sculptor, and was capomaestro at the Duomo for 50 years, from the death of Raffaello da Montelupo in 1566 until his own death, by which time he was 85 years old.

Fabiano Toti, who was born in Orvieto, was a pupil of Ippolito Scalza, under whom he worked at the Duomo.

Orvieto

Duomo

Throughout his career, Ippolito Scalza was centrally involved in the remodelling of the Duomo. Some of his work still survives in the Duomo.

Cappella della Visitazione (1547-54)

In the central relief, the meeting between the Virgin and St Elizabeth prior to the birth of their respective sons is set among buildings that are sketched in deep perspective. Francesco Mosca must have been very proud of this work, because he suggested that the Opera del Duomo should take advice from Michelangelo as to it value. In the event, this suggestion does not seem to have been taken up.

Prophets (1555-6)

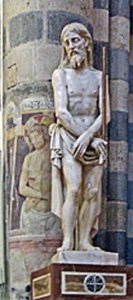

St Sebastian (1556-7)

Francesco Mosca had selected marble for this figure in 1554, but it was unfinished when he left Orvieto in 1556. Ippolito Scalza finished it, and it was then placed in the new niche to the left the entrance to the Cappella Nuova. It was moved to the counter-facade, probably in ca. 1593, where it formed a pendant to a figure (1593) by Fabiano Toti of St Roch, another plague saint. Both are now exhibited in the ex-church of Sant’ Agostino.

Sacramental Tabernacle (1554-64)

In 1554, the Opera del Duomo and Compagnia del Corpus Christi commissioned a new tabernacle for the consecrated host, which was to stand on the high altar. The initial plan was for a marble tabernacle, but this was changed to gilded wood, probably so that the structure could be executed on a more monumental scale. This was one of the earliest sacramental altars of its type in Italy and was designed to be placed on the high altar, where it would provide the devotional focus of the church.

Raffaello da Montelupo completed the design of the tabernacle in 1558 and Ippolito Scalza executed it in 1558-60. It was installed in ca. 1560 and gilded in 1563. Cesare Nebbia painted eleven panels for it soon after. The tabernacle, which was moved from the high altar to the back of the tribune in 1629, was destroyed in the late 18th century. The panels by Cesare Nebbia were re-discovered recently and are now exhibited in the Museo del Opera del Duomo.

Chapels in the Nave (1570-75)

In 1564, Ippolito Scalza was commissioned to decorate one of the new stucco altars in the left aisle, to a design by Raffaello da Montelupo. In 1570, some three years after his appointment as capomaestro, he wrote to the Opera del Duomo to urge that marble should be used for the altars in the right aisle, pointing out that the earlier stucco work in the left aisle was already deteriorating. However, the decision ultimately went against him. The programme was completed in stucco by ca. 1575. These chapels were destroyed in ca. 1890.

Facade

Ippolito Scalza completed the façade by building the two outer towers in 1571-91.

Pietà (1570-9)

-

✴the Pietà (1499), which was conceived for an altar in the funerary chapel of Cardinal Jean Bilherès in Santa Petronilla, Rome and is now in St Peter’s, Rome; and

-

✴the Pietà (ca. 1550), which was probably intended for Michelangelo's own funerary monument and which is now in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence.

The commission was given to Raffaello da Montelupo, but by the time that the marble for the work arrived in Orvieto (in 1570), he was dead. The commission therefore passed to his successor, Ippolito Scalza.

The group comprises the dead Christ and Madonna with St Mary Magdalene and Nicodemus. It is carved from a single block of marble (except for the left arm of Nicodemus and the upper part of the ladder that he is holding). Scalza signed the base of the completed work in 1579.

Unlike the earlier works by Michelangelo, the Orvieto Pietà was commissioned with no particular function and no specific location in mind. Given the Eucharistic significance of the work, it is surprising that it was never incorporated into the iconographical programme of the body of the church. It was instead "provisionally" installed in front of the fresco of the Pietà by Luca Signorelli in the Cappellina dei Corpi Santi of the Cappella Nuova.

The sculpture immediately became the main object of devotion in the chapel, and over-shadowed Signorelli's frescoes there. Scalza wrote to the Opera del Duomo in 1588 pleading for a more appropriate location to be found, not least because the work was vulnerable to damage. This plea went unheeded, and the chapel had to be locked in 1590 to ensure that the sculpture was not damaged. In 1609 (during the debate about the location of the figures of the Annunciation by Francesco Mochi), it was decided that it should be placed in front of the tabernacle on the high altar, but this plan was never put into effect. The group remained in the Cappella Nuova until early in the 20th century, when it was moved to its current location at the junction of the nave and the right transept.

Monument to Bishop Sebastiano Vanzi (1571)

Bishop Sebastiano Vanzi was an eminent jurist who distinguished himself at the Council of Trent in 1562-3. His will of 1567 contained a substantial bequest to the Opera del Duomo. He intended that this should finance, among other things, a bronze tomb in front of the high altar, which would be used for his own burial and for those of his successors. Work on the design was started, but the project came to a halt after Bishop Vanzi retired in 1570. He died a year later.

Bishop Vanzi had also suggested that part of his bequest should be used each year for a temporary model of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which would be erected in the Cappella del Corporale to house the reserved Host during Easter week. In the event, a tomb in local stone (which was much cheaper than bronze) was erected for Bishop Vanzi in this chapel. His marble bust above the sarcophagus was positioned so that he would be seen to participate in the annual services at the temporary sepulchre.

Organ (1580-8)

The organ survives in its original location.

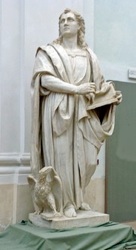

Apostles (1587-99)

St Thomas St John the Evangelist St Andrew

by Ippolito Scalzi by Ippolito Scalzi by Ippolito Scalzi and Fabiano Toti

The Opera del Duomo sent Ippolito Scalza to Carrara in 1579 to obtain marble for four statues of the Apostles, which would supplement figures of St Paul (1566) and St Peter (1560) that were already in place against the columns of the nave nearest the crossing. This initiated a programme of work that would eventually see all twelve Apostles represented in the nave.

-

✴Ippolito Scalza executed the first two new Apostles:

-

•St Thomas (depicted as an architect) was installed with great ceremony in 1587; followed by

-

•St John the Evangelist (1588-94).

-

✴In 1589, the third block of marble was assigned to Fabiano Toti for a figure of St Andrew,. He duly submitted a design, and was documented at work on the figure in 1589-90. However, the commission passed to Ippolito Scalza in 1594 and it was not completed until 1599.

All of the statues in this series are now in the ex-church of Sant’ Agostino.

Ecce Homo (1608)

Restoration of Palazzo Soliano (1564-70)

The Commune transferred Palazzo Soliano to the Opera del Duomo in 1550. They commissioned Ippolito Scalza to carry out restoration work in 1564-70.

Palazzo Clementini (1567)

Monaldo Clementini commissioned Ippolito Scalza to build Palazzo Clementini, but it was still incomplete when Cornelio Clementi inherited it in 1577. Francesco Clementini left money in his will of 1687 for the completion of the facade. Nevertheless, photographs taken in the 19th century show that this facade was still barely started at that point. The Commune bought the palace in 1912. It owes its current appearance to the "restoration" of the facade (1937) by Gustavo Giovannoni.

Well Head(1571)

Completion of Palazzo Monaldeschi (1570-4)

According to Giorgio Vasari, Simone Mosca executed “the ground plans of some houses for the honourable Counts della Cervara”. These probably included Palazzo Monaldeschi, which was commissioned by Sforza Monaldeschi della Cervara. The design is unusual for Orvieto in that the palace has an internal courtyard surrounded by a loggia.

The historian Monaldo Monaldeschi, who was the brother of Sforza, recorded in 1584 that the palace was extended after the reign of Pope Pius IV (died 1565). Ippolito Scalza, who designed ten windows (1572) and the ceiling of its living room (1574), presumably brought the project to completion.

Palazzo del Governatore (1571-98)

Work began on a new phase of restoration of this palace (previously Palazzo dei Sette) in 1571, almost certainly under the direction of Ippolito Scalza. The arms of Pope Pius V over the main external portal, which are attributed to his cousin Lodovico Scalza, are dated by inscription to 1571. The original prison in the palace were restored and a new entrance area was built in 1577-8. Smaller restoration works continued in the 1580s. An oratory was fitted out in 1591, with a communication window that allowed services in San Rocco to be observed. Work on the rooms on the first floor overlooking what is now Corso Cavour was carried out in 1598. The inscriptions in the main entrance hall, which probably relate to this phase of restoration, commemorate:

-

✴Orazio Benedetto da Cagli, Governor in 1578;

-

✴Ferrante Ferri, Governor in 1585; and

-

✴Gaspare Paluzzi Albertoni, dated 1598.

Palazzo Comunale (1574)

Antonio da Sangallo il Giovane was commissioned to provide a model for a new public palace to replace the Palazzo Comunale in 1532. The project stalled until 1563, when the loggia of the palace facing Sant' Andrea had to be demolished because it threatened to collapse. In 1573, Ippolito Scalza was finally commissioned to rebuild the palace according to the design by Antonio da Sangallo il Giovane. In fact, his design, which survive in the Museo dell'Opera, seems to have been very much his own.

Ippolito Scalza intended to re-use the existing fabric of the palace and to extend it, so that the ground floor loggia would comprise the seven original arches and four more to the right. Work duly started in 1573, but it was abandoned in 1581, before the extension had begun. This change of plan is obvious from the current appearance of the facade: the second arch from the right, which is distinguished by double columns, was obviously meant to be the central portal of the palace. The present Via Garibaldi, which was almost certainly intended that it should be diverted to pass through this arch, in fact passes through the original central arch, two arches to the left of it.

Convento di San Francesco (1580)

Ippolto Scalza rebuilt part of the Convento di San Francesco, including the cloister in 1580. This cloister can be seen from inside the Biblioteca Luigi Fumi, which moved to the part of the convent to the right of the church in 2009.

Palazzo Saracinelli (1580)

The windows on the first floor, which seem to have been built at different times, have inscriptions recording Pantaleone, Bernardino and Francesco Saracinelli.

Work in Chiesa dell’ Annunziata (1585-97)

-

✴the main altar and two stucco side altars, in 1585; and

-

✴the wooden choir (1592-7).

He also provided a design for the facade, but this work was only partially carried out.

Completion of Palazzo Crispo Marsciano (ca. 1586)

Ludovico di Gasparo dei Conti di Marsciano bought the incomplete palace in 1586. The work he commissioned, which included the windows in the upper storeys, is attributed to Ippolito Scalza.

Water stoup (1588)

Palazzo Simoncelli (13th century, restored 16th century)

Giannotto Simoncelli restored Palazzo Simoncelli, which nevertheless incongruously preserves some elements of the original medieval building on its facade. Giannotto is commemorated in the architraves of a number of the windows.

The ornate window to the right of the portal commemorates his son Tiberio Simoncelli, who probably commissioned it. He also seems to have commissioned the balcony above the portal, which is attributed to Ippolito Scalza.

Palazzo Carvajal (16th century)

-

✴An inscription to the left of the frieze below the first floor windows announces in Spanish that Carvajal des Carvajal built the palace for the convenience of his friends.

-

✴Another in Latin over the portal states that it is open for good, not for evil.

The palace is often attributed to Ippolito Scalza; however, Augusto Roca de Amicis (referenced below) suggests that his hand can only be easily recognised in the main portal.

Work on San Lorenzo delle Vigne (17th century)

Amelia

Monument to Baldo Farrattini (1561-4)

The epitaph commemorates Baldo Farrattini, who died in 1567. It records that Baldo had commissioned the chapel, which was to house his own monument and that of his uncle, Bartolomeo II. It is highly likely that he also commissioned this monument for his own eventual use. In the monument, Baldo (who was still alive when the work was carried out) lies in effigy on top of the sarcophagus. His head is resting on his hand: he could be asleep but he could also be meditating on the image of the Risen Christ in the relief above him. The monument is clearly inspired by the central section of the funerary monument of Cardinal Ascanio Sforza in the retro-choir of Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, which Pope Julius II commissioned from Andrea Sansovino.

An itinerary that survives in the sketchbook of Giovanni Antonio Dosio in the Staatsbibliothek, Berlin records that Dosio left Orvieto in April for Amelia, where he stayed until July stayed to work with Ippolito Scalza. Another surviving document records that Dosio’s work involved the funerary monument of “vescovo Farratino”. This was almost certainly the monument to Bartolomeo II Farrattini mentioned above. These monuments were visually linked to the Farrattini Altarpiece, which is attributed to Federico Zuccari. Each of these artists was, like Ippolito Scalza, just beginning his independent career. The circumstances in which they probably gained these commissions are set out in the page on Cappella Farrattini.

Obviously, this project could not have been achieved in a few months in 1564: the factors that suggest the period 1561-4 are also set out in the page on Cappella Farrattini. These include the fact that Ippolito Scalza was documented in Amelia in 1562, and was otherwise absent from the records of the Opera del Duomo, Orvieto (his usual employer) from February 1561 until September 1564.

Narni

Palazzo Scotti (1567)

-

✴it was built for Cardinal Giovanni Bernardino Scotti (died 1568), whose arms are frescoed on the ceiling of a room on the ground floor; and

-

✴it can be attributed on stylistic grounds to Ippolito Scalza, who wrote to his employers, the Opera del Duomo of Orvieto, in February 1567, requesting leave of absence to travel from Narni to collect an outstanding payment. If the attribution is correct, this is the earliest palace that he designed.

Todi

Santa Maria della Consolazione (1508-1609)

Tempio del Santissimo Crocifisso (1589-1606)

Portal of Palazzo Cesi (ca. 1600)

[Other works in Todi]

Read more:

F. Piagnani and L. Principi, “La Scultura del Cinquecento in Orvieto”, in

C. Benocci et al. (Eds), “Storia di Orvieto: Quattrocento e Cinquecento” (2010) Pisa, Volume II, pp 585-636

M. Cambareri and A Roca de Amicis, “Ippolito Scalza (1532-1617)”, (2002) Perugia

M. Cambareri, "Ippolito Scalza e la Transformazione del Duomo di Orvieto nel '500: le Sculture Marmoree", in

G. Barlozzetti (Ed.), "Il Duomo di Orvieto e le Grandi Cattedrali del Duecento", Turin (1995 ), pp 199-212

Return to the page on Art in: Amelia Foligno Narni Orvieto Todi.