Text

The city did not form its archaeological collection until 1871, by which time many of its most important ancient treasures had found their way into other collections in Rome and elsewhere.

Bronze Panel (ca. 6th century BC)

Museo Archeologico, Florence

This panel, which seems to come from a chariot, was found in1870 in the Le Logge area of the necropolis. It was probably made in Volsinii. The relief on the panel depicts Thetis giving a new set of armour to her son Achilles. (Achilles had lent his original armour to his friend Patroclus, but the Trojan Hector had taken it after he had defeated Patroclus in combat).

Grave Goods from Tomb of a Warrior (late 5th century BC)

Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Rome

This tomb was found in the San Raffaele area of the necropolis in 1914. While there were a number of graves in the adjoining properties, this one seems to have been relatively isolated. The deceased had been buried in a trench grave on an east-west axis, along with his weapons and armour and with the necessities for a ritual banquet. Some sixty Attic vases in the tomb had been collected over a period of about a century prior to his death. His beautifully inscribed helmet with hinged cheek pieces (which was probably for ceremonial rather than practical use) had been modelled on those worn by Etruscan warriors in the 5th century BC. This important object was found in pieces and reassembled.

Mars of Todi (late 5th century BC)

Museo Gregoriano Etrusco, Vatican, Rome

This image and the detail below are

courtesy of Dr Rozmeri Basic

This bronze nearly life-sized figure of a warrior (which weighs about 90 kg) was found in 1835 in a travertine-lined grave at Montesanto outside Todi. This was the site of an ancient sanctuary that was apparently dedicated to an Umbrian deity based on the Greek Ares (Roman Mars). The statue was probably ritually buried after it had been struck by lightening. The figure in the state, which probably represented Ahal Trutitis himself, once leaned on a lance and seems to have been pouring a libation, presumably before going to war. The Commune sold the statue to the Papal Governor in 1836.

ahal trutitis dunum dede

This records the donation of some kind, probably to a God, by a man called Ahal Trutitis, who (judging by his name) was probably of Gallic descent. (It is interesting to note that a bilingual Latin/Gallic inscription (late 2nd century BC) was found at nearby Vicus Martis Tudertium (Massa Martana)).

The inscription is also described in the page on Early Italic Inscriptions.

Grave Goods from a Lady's Tomb (ca. 300 BC)

Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Rome

This tomb, which was found in the Peschiera area of the necropolis in 1886, was exceptionally rich. The deceased was buried in a dress woven with gold thread and with her magnificent golden jewellery, a fine mirror engraved with the scene of the judgement of Paris and numerous other artefacts of Etruscan manufacture. These include: a bronze wine pitcher whose cast handle is formed by a naked, bearded satyr; and a double-handled pottery vase with the head of a satyr on one side and a maenad on the other. These objects were perhaps a hundred years old at the time of their burial. She also had a collection of gold coins with which to pay for her journey to the next world.

Grave Goods from Peschiera (ca. 300 BC)

Museo Nazionale di Villa Giulia, Rome and Museo Archeologico, Florence

These exhibits came from the 19 tombs that were found in the Peschiera area of the necropolis in 1891. Tomb VII, which must have belonged to a warrior, contained a bronze helmet that is now in Rome. Tomb XX, which was near to the lady’s tomb that had been discovered in 1886 (see above), contained some similar objects, including an engraved mirror showing Helen being dressed by her attendants that is now in Florence.

Tiles with Grave Inscriptions (2nd century BC)

Museo Oliveriano, Pesaro

These four tiles originally sealed grave niches in Todi. One inscription uses an Etruscan alphabet, while the others use the Latin alphabet.

Bi-lingual Funerary Stele (2nd century BC)

Museo Gregoriano Etrusco, Vatican, Rome

This extraordinary epitaph was found in the area of the Vicus Martis Tudertium near Massa Martana. It is written in Gallic (using an Etruscan alphabet) and then again in Latin on each side of the stone. It commemorates the fact that Coisus, son of Brutus placed a cinerary urn of his older brother Atagnatus, in a tomb that he had erected. The names indicate that this family was of Gallic descent, and this is the earliest Latin inscription found in the vicinity of Todi. (The name on the Mars of Todi seems to be of someone of Gallic provenance.)

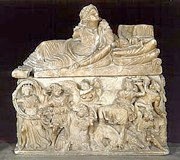

Cinerary Urn (early 2nd century BC)

Museo Gregoriano Etrusco, Vatican, Rome

This magnificent urn had a married couple reclining on its lid (although the figure of the husband was later removed) It is attributed to the so-called "Maestro di Enomao’, and probably came originally from Volterra. It was discovered in 1516 during excavations on the site of the Rocca to provide material for the construction of Santa Maria della Consolazione. It had probably been re-used for a burial in the crypt of the Abbey of San Leucio, which had stood on this site from the 10th century until its demolition in 1371. The male figure on the lid was presumably removed at this time, perhaps because the deceased on this second occasion was a single woman. The urn was displayed in Todi after its discovery until 1772, when the authorities gave it to Pope Clement XIV. This was certainly in return for his adjudication in their favour in their long-running dispute with the Franciscans over rights to San Fortunato, and for his remission of taxes in that year in order to allow the restoration of a section of the walls.

The relief on the front of the urn depicts a scene from the murder of Oenomaos. According to Greek mythology, Oenomaos, king of Pisa decided to hold a chariot race for the hand of his daughter, Hippodameia. When an oracle then told him that his daughter would cause his death, he ordered that all suitors should be killed during the race. However, Pelops (one of the suitors) managed to kill Oenomaos with the help of his patron god Poseidon. He then married Hippodameia and founded the Olympic games, perhaps to purify himself after the murder or perhaps as an act of thanksgiving to the gods for his victory.

Inscribed Base of a Statue of Jupiter (late 1st century AD)

Unknown

This inscription (CIL XI:2 4639; ILS 3001) reads:

Pro salute/coloniae et ordinis decurionum/ et populi/ Tudertis,

Iovi opt(imo]) max(imo)/custodi conservatori/

quod is sceleratissimi servi/ publici infando latrocinio | defixa monumentis ordinis/ decurionum nomina/ numine suo ervit

ac vindi/cavit et metu periculorum/ coloniam civesque liberavit

L(ucius) Cancrius Clementis lib(ertus)/ Primigenius/ sexvir et Augustalis et Flavialis/

primus omnium his honoribus ab ordine donatus/ votum solvit

For the well-being of the colony and the order of councillors and the people of Tuder, to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, guardian and preserver:

-

-because he [Jupiter] removed by his divine power the names of members of the order of councillors that had been affixed to tombs [ ??] by the outrageous criminal action of a most accursed public slave; and

-

-because he [Jupiter] vindicated and freed from fear of danger the colony and [its] citizens;

Lucius Cancrius Primigenius, freedman of Clemens, sevir Augustalis and Flavialis, who was the first to be honored in this way by the order of councillors, fulfilled his vow [to Jupiter by erecting this statue].

In other words, a slave had placed a curse on members of the local council by fixing plaques of some kind inscribed with their names on something usually translated as “tombs”. Primogenius persuaded Jupiter to remove the threat in return for the dedication of a statue.

The inscription tells us that Primigenius was the first member of the new association of six men that had been formed in Todi to preside over the combined cults of the Augustales and Flaviales, both of which were associated with emperor worship.

-

✴The seviri Augustales, which was an association of six men dedicated to the cult of Augustus and the other Julio-Claudian emperors, had probably existed in Todi from the earliest days of the colony.

-

✴The extension of their sphere of activity probably occurred soon after the formation of the new, dynastic Flavian cult by Domitian (died 96 AD) for the veneration of his deified father and brother, Vespasian and Titus. For the background, see the material on the Flavian cult in the page on the Rescript of Constantine.

This is one of only about 13 inscriptions recording a sevir Flavialis in an Italian municipality: in almost all the known cases, the municipality concerned had, like Tuder, combined the roles of serviri Augustales and seviri Flaviales.

The date of the inscription can be deduced from the epithet given to Jupiter: “custodi conservatori”. This indicates a direct link to Domitian, who had found refuge in a small chapel to Jupiter Conservator during the civil war of 69 AD and who had subsequently replaced it with a more expansive one that he dedicated to Jupiter Custos. This overt reference would have been unacceptable after his damnatio memoriae, so that the statue must have been commissioned before his death. (It seems then that the extension of the imperial cult to the new Flavian dynasty included the veneration of the living Domitian, at least at Tuder.

The inscription was published in “Nouvel Esprit des Journaux Français et Étrangers” (January 1784, pp 427-8) in a short article that named the source of the information as Abate Andrea Giovanelli.

[Where and when was this inscription found, and where is it now ??]

[If you came here from the pages on the Rescript of Constantine at Hispellum, this link will take you back]

Return to the home page on Todi.