Sumerian King List (SKL)

Cyrus the Great and the Kingship of Sumer and Akkad

Inscribed clay cylinder known as the ‘Cyrus Cylinder’ from the foundations of the wall of Babylon

Image from the site of the British Museum, where the tablet is now housed (BM 90920)

We know from the cuneiform text that is inscribed (in the Babylonian dialect of Akkadian) on what we know as the ‘Cyrus Cylinder’ (illustrated above) that, when the Persian king whom we know as Cyrus the Great captured Babylon in 539 BC, he introduced himself to his new Babylonian subjects as:

-

“... king of the world, great king, strong king, king of Babylon, king of the land of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four quarters (of the world), ... the eternal seed of kingship, whose reign the gods Bel (Marduk) and Nabu love, whose k[ingshi]p they desired to their heart’s content”, (RIMB, Cyrus II, 1: 1, 20-22).

At least three of these royal titles:

-

✴king of the world;

-

✴strong king; and

-

✴king of the four quarters (of the world);

date back to the so-called Sargonic period (ca. 2300), during which Sargon and his successors presided from Akkad over one of the earliest empires known in history.

Interestingly, as Jasmina Osterman (referenced below, at p 63 and note 96), observed, another of Cyrus’ titles, ‘king of Sumer and Akkad’ (LUGAL KUR-šu-me-ri ù ak-ka-di-i), dates back to a slightly later empire, that of the so-called Ur III dynasty (ca. 2100 BC). More specifically, as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2019, at pp. 151-2 and note 409) observed:

-

“... the founder of [this] dynasty, Ur-Namma, coined for himself a completely new title, which was ‘king of Sumer and Akkad’.”

An important example of this usage is known from the Old Babylonian copy of a Sumerian original that was found in the Mesopotamian city of Isin:

-

“(I), Ur-Namma, mighty man, king of Ur, king of the lands of Sumer and Akkad (lugal ki-en-gi ki-uri), dedicated (this object) for my life. At that time, the god Enlil gave (?) ... to the Elamites. In the territory of highland Elam, they (Ur-Namma and the Elamites) drew up (lines) against one another for battle. Their (??) king, Puzur-Inshushinak, ... (the cities of) Awal, Kismar, Mashkan-sharrum, the lands of Eshnunna, the lands of Tuttub, the lands of Simudar, the lands of Akkad, all the people ...”, (RIME 3/2: 1: 1: 29, lines 11-23; see also the translation by Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 2008b, at p. 35).

It is therefore possible that Ur-Namma, the king of Ur (the city from which he exercised hegemony over the land of Sumer), adopted the additional title ‘king of Sumer and Akkad’ after his ‘liberation’ of the more northerly city of Akkad from the hegemony of the Elamite king Puzur-Inshushinak. Interestingly, is Paul-Alain Beaulieu (referenced below, at p. 52) observed, it was at about this time that Babylon first:

-

“... emerged from obscurity and became a provincial centre of some consequence, the capital of one of the provinces that formed the core of the Ur III state.”

Now, some 1,500 years later, Cyrus exercised hegemony over Sumer and Akkad by virtue of his conquest of Babylon.

We do not know nearly enough about Cyrus himself to establish how he regarded this Mesopotamian heritage. It is possible that he had simply adapted the titles that the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal had used after he had expelled his brother from the governorship of Babylon in 648 BC: for example:

-

“I, Ashurbanipal, great king, strong king, king of the world, king of Assyria, king of the four quarters (of the world), offspring of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, governor of Babylon, king of the land of Sumer and Akkad, descendant of Sennacherib, king of the world, king of Assyria”, (RINAP 5: Ashurbanipal 003: see also 004. 005 and 010);

particularly since he recorded in the ‘Cyrus Cylinder’ text that he had seen an inscription in Babylon that had been written:

-

“... in the name of Ashurbanipal, a king who came before [me] ...”, (RIMB, Cyrus II, 1: 1, 43).

However, having said that, it is surely significant that the ‘Cyrus Cylinder’ text makes multiple references to the land of Sumer and Akkad (= the territory that we know as Babylonia):

-

✴before their conquest by Cyrus in 539 BC:

-

•‘... the people of the land of Sumer and Akkad ... had become like corpses”., (line 11); and

-

✴after their conquest by Cyrus:

-

•“the people of Babylon, all of them, the entirety of the land of Sumer and Akkad ... bowed down before him (and) kissed his feet”, (line 18); and

-

•“the deities of the land of Sumer and Akkad [were able] ... to live in peace in their abodes”, (line 33).

Thus, it seems to me that, at least in the Mesopotamian part of his empire, Cyrus might well have been regarded as the holder of the kingship that had once been held by Ur-Namma.

This brings us to the subject of the present page, the so-called Sumerian King List (SKL): as we shall see, Ur-Namma was the last king recorded in the earliest surviving recension of this list, which was commissioned by his son and successor, Shulgi. This text (of which just over half survives) originally recorded about 80 holders of kingship, dating back to the mythical Gushur, who had ruled from Kish when kingship had first descended from heaven. At least by the time of Ur-Namma, the kingship in question was obviously that of Sumer and Akkad. Thus, by adopting this title, Cyrus (or, at least, his Babylonian advisors) laid claim to this Mesopotamian heritage (alongside his heritage from his own forebears, who were identified in the ‘Cyrus Cylinder’ text as great kings of Anshan).

Discovery of the Sumerian King List (SKL)

Old Babylonian Recension of the Sumerian King List (SKL) on the so-called Weld-Blundell (WB) Prism

Now in the Ashmolean Museum: image from the museum website

The clay prism illustrated above contains a Sumerian cuneiform text (transliterated as CDLI, P384786) from the so-called Old Babylonian period (ca.2000-1600 BC), which records the kings of a succession of cities in Sumer and its neighbouring regions, together with the lengths of their respective reigns. The list extends over a considerable period:

-

✴the first king in the list, Alulim, ruled at Eridu before the (biblical) flood; while

-

✴the last-named, Sin-magir, ruled at Isin in ca. 1800 BC.

The provenance of the prism is unknown:

-

✴it was first recorded as part of the private collection of Herbert Weld-Blundell, who presented it to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford in 1923; and

-

✴Stephen Langdon (referenced below) published it (as WB 444) shortly thereafter.

By that time, fragments of similar texts had been known some years, but the connections between them only became apparent after the publication of the essentially complete WB 444.

When, in 1939, Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below) published the first critical edition of what was by then known as the Sumerian King List (SKL), he was able to rely on WB 444 and 14 other (less complete) texts (which he listed at pp. 5-13). In 2004, Jean-Jacques Glassner (referenced below, at pp. 118-25) published an updated version of WB 444 (his ‘manuscript G’, see p. 117), which he entitled ‘Chronicle of the Single Monarchy’ (for reasons that will discussed below). See Table 1 (below) for the labelling of individual recensions used by Jacobsen and by Glassner.

Since then, the SKL corpus has expanded from 14 to 26 recensions, and these are the subject of a critical edition that Gösta Gabriel is about to publish: I would like to express my gratitude to Dr Gabriel for allowing me to read a pre-publication copy of this important (and much-needed) book. As we shall see, one of these is considerably older than the rest: the recension mentioned above that ended with Ur-Namma, which unfortunately remained unpublished until 2003.

Modern Corpus of the SKL Recensions

Table 1: Summary of the SKL corpus published by Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming)

Sallaberger and Schrakamp = Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at pp. 15-22)

Glassner = Jean-Jacques Glassner (referenced below, at pp. 117-8)

Jacobsen = Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below, at pp. 5-12)

(For convenience, I have numbered the 24 Old Babylonian recensions sequentially in the lefthand column)

The corpus analysed by Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) is summarised in Table 1 above. Unfortunately, there is at present no universally recognised method of labelling the individual texts:

-

✴Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) uses the labels in the second column, which reflect the locations of the respective find spots (where these are known); and

-

✴the following three columns give the alternative labels used in other important sources (see the references in the table notes).

As Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 235) pointed out:

-

✴24 of the 26 manuscripts in the corpus (which I have labelled these as numbers 1-24 in the column at the extreme left) date (like WB 444 = number 24) to the Old Babylonian period: and

-

✴there are two ‘chronological outliers’:

-

•the oldest known copy of the SKL was compiled in so-called Ur III period (ca. 2100–2000 BC), for which reason it is usually referred to as the USKL; and

-

•a single later manuscript probably dates to ca. 1600–1450 BC.

As noted above, we must await the publication of Gösta Gabriel’s forthcoming book for a complete edition of these 26 manuscripts. Meanwhile, convenient on-line sources for the Old Babylonian text include:

-

✴a composite transliteration and translation at CDLI (P479895); and

-

✴a composite translation divided by ‘city dynasties’ (see below) at ETCSL (translation: t.2.1.1).

In what follows, references to specific lines in these texts use the numbering system used by the CDLI.

Opening Lines of the USKL and the SKL Recensions

Although many of the surviving SKL recensions are fragmentary, we can be reasonably sure that they all began with essentially the same account of the descent from heaven of kingship (nam-lugal), an undefined privilege that the gods had conferred on a particular place (which, by implication, became the first city to be ruled by a king). More specifically, each of the recensions that are reasonably complete in their opening sections can be assigned to one of two groups:

-

✴in some (picked out in pink in Table 1), the gods first bestowed kingship on Kish, where Gushur was king; and

-

✴in others (picked out in blue in Table 1) :

-

•the gods bestowed kingship on Eridu, where Alulim was king;

-

•he was the first of eight kings who ruled in succession in Eridu or one of four other cities before ‘the flood swept over’; and

-

•thereafter, when kingship returned from heaven, it was bestowed on Kish, where Gushur was king.

Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below, at p 63), who was unaware of the existence of the USKL tablet (see below), concluded (on linguistic grounds) that:

-

“The role of the antediluvian section in the tradition of the [SKL] can no longer be doubted: it is a later addition.”

The case for this hypothesis was greatly strengthened by the publication of the USKL, so that (some 80 years later) Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2019, at p. 59) was able to restate it in even stronger terms:

-

“As is universally agreed by all the modern students of the SKL, the antediluvian section represents a later addition. This is confirmed by the fact that the [Antediluvian King List (AKL)] is not part of the [USKL]. ... The precise date at which this section was added to the SKL cannot be ascertained with certainty. However, the fact that [it] is closely connected with the ‘Deluge tradition’, whose earliest attestations seem to belong to the 20th century BC, indicates that this happened either in the Isin-Larsa period or sometime later in Old Babylonian times. ”

Thus, we can initially put the AKL preface to one side while we analyse the ‘SKL proper’ as it evolved over time.

USKL Recension

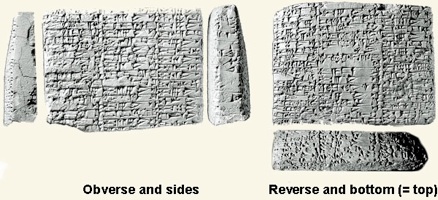

Surviving part of the tablet containing the Ur III recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL):

the tablet is in a private collection and the image adapted from CDLI: P283804

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003), to whom we owe the publication of the only surviving USKL tablet, provided a transliteration of and an important initial commentary on the text. A transliteration and photographs are also available on line at CDLI: P283804. In what follows, references to specific lines in these texts adopt the numbering system used by the CDLI.

The surviving USKL text is arranged in three columns on each side of this tablet fragment (with that on the reverse sometimes continuing onto the bottom). Since the opening and closing lines of the original text survive, we know that:

-

✴it begins (at obverse, col. 1, line 1) with the claim that:

-

“After kingship was brought down from heaven, Kish was king. In Kish, Gushur ruled for 2,160 years”, (see the translations by Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, at p. 231 and Gösta Gabriel, 2023, referenced below, at p. 247); and

-

✴it ends with:

-

•the name of Ur-Namma, the founder of the ‘Ur III’ dynasty (reverse, col. 3, lines 21-2); and

-

•the scribe’s dedication of his handiwork to Shulgi, his king (see below).

Shulgi was the son and successor of Ur-Namma, the founder of what historians know as the ‘Ur III’ dynasty (for reasons that will become clear below).

I discuss this important recension in more detail in my page Ur III Recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL): in this section, I provide a brief summary, in order illuminate the part that it subsequently played in the more complex later recensions.

Kish A List

Table 2

As indicated in the table above, the surviving text on the obverse of the USKL tablet includes the opening declaration quoted above. This was followed by the names of 21 rulers of Kish (each of which is followed by the corresponding reign length). Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 237 and note 17) labelled this list as ‘Kish A’.

Piotr Steinkeller established that the original USKL text had been structured around a series of king lists, the first of which originally named about 30 kings of Kish covered the period:

-

✴from Gushur (in time immemorial); to

-

✴the otherwise unknown Meshnune;

which represented about 40% of the total number of kings in the original text. As is set out in Table 2, the names of 21 of these kings are recorded in the surviving text.

Uruk A* List

Table 3

The text in column 3 on the obverse of the surviving USKL tablet:

-

✴was broken immediately after the record of the Kishite king Meshnune, son of Nanne (see Table 2); and

-

✴began again about half way down the first column on the reverse, with the information that Sargon ruled in Akkad for 40 years as set out in Table 3.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 274) observed that the completion of the intervening lacunae (labelled Lacuna 3a and lacuna 3b in the tables above) is extremely problematic. However, as he pointed out, we at least know that the last of these rulers was almost certainly Lugalzagesi of Uruk, whom Sargon of Akkad famously defeated, thereby becoming the king of both Akkad and Sumer. In what follows, I assume, with Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, note 16, at p. 237) that:

-

“Uruk is the most likely candidate for reconstructing the missing section of the text”.

He estimated that there would have been about nine kings (including Lugalzagesi) in this list, which he labelled Uruk A* (with the asterisk indicating uncertainty).

Remaining USKL King Lists

The surviving text in column 1 on the reverse of the tablet contained the names of:

-

✴Sargon and his four successors at Akkad; and

-

✴the names of four men who subsequently aspired to the throne of Akkad in what scholars refer to as the ‘period of confusion’ (during which Akkad came under pressure from invaders from Gutium).

According to Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 275) the lacuna that followed (my Lacuna 4) contained the names of four kings known from the SKL:

-

✴Dudu and Shu-Turul, the last two kings of Akkad; and

-

✴Ur-nigin and Ur-gigir, the two kings who preceded Kuda at Uruk (see also Table 11 below).

Then came:

-

✴the Gutians, characterised as the ummanum (hordes or army), 4-5 of whom were probably recorded in my Lacuna 5;

-

✴Utu-hegal of Uruk , who claimed in a royal inscription to have recovered Sumer from the Gutian king Tirigan; and, finally

-

✴Ur-Namma of Ur.

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 237 and note 17) labelled these respective king lists as:

Akkad - Uruk A - Gutium - Uruk B - Ur A.

Date of the USKL

As noted above, the list ended with the scribe’s dedication of his handiwork to:

-

“... [the divine] Shulgi, my king: may he live until distant days (translation based on that by Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2003, at p. 269).

Although, as Steinkeller acknowledged, it is theoretically possible that the text on the only known USKL tablet is a later Ur III copy of the original, he argued that:

-

“... by all indications, Shulgi was still alive when [the surviving text] was written down, as the invocation suggests.”

In fact, we can probably be more precise: Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 269) argued that, since Shulgi was given a divine determinative in this dedication, it must have been compiled at some time between:

-

✴his 20th regnal year (the approximate date of his deification); and

-

✴his 48th regnal year (the approximate date of his death).

Terminology

Modern historians mostly refer to the ruling cities of the kings named in the USKL (and in the SKL) as ‘dynasties’ (so that, for example, Ur-Namma and the other ‘Ur III’ kings are so-called because, at least in the SKL, they ruled at Ur when kingship was transferred there for the third time in its history. However, there is a problem with this usage of the word ‘dynasty’: as Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 13) pointed out, this differs from the general usage, in which the word refers to a group of successive rulers from the same family (or blood-line) .

Piotr Michalowski (referenced below, 2013, at p. 6448), addressed this problem by replacing the word ‘dynasty’ in the present context with ‘hegemony’: thus, for example, he described the SKL as:

-

“... a Sumerian school composition that records a sequence of hegemonic cities and kings from primordial times to the dominion of the Isin Dynasty in the 18th century BC.”

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at note 12, at p. 236) similarly argued that:

-

“Because the term ‘dynasty’ is commonly used to describe a set of rulers connected by family ties, ‘hegemony’ is better suited to denote the reign of a city in the [USKL and] SKL, whose rulers are not necessarily connected by a single bloodline.”

While this is an excellent point, it seems to me that the use of the word ‘hegemony’ raises its own problems: for example, we have no reason to think that Gushur was ever believed to have exercised ‘hegemony’ outside Kish. For this reason, in what follows, I retain the conventional practice of referring to the ruling cities of the USKL and the SKL as ‘dynasties’, but I use the terms ‘city dynasty’ and/or ‘familial dynasty’ when the meaning is otherwise unclear.

Dynastic Structure of the SKL Recensions

Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 234) observed that:

-

“... there is no single, uniform text of the Sumerian King List (henceforth, SKL). It exists in a multitude of variants; none of its known copies reproduces exactly the same text. [It can therefore] be called a ‘fluid text’. ... meaning that it was subject to a continuous process of revision and transformation. Each of its copies integrated new ideas into the traditional text. ... However, there is also a stable core of the story:

-

✴It always begins with the divine transfer of kingship from heaven to earth into a first city.

-

✴This city turns into the capital, its kings ruling the entire land.

-

✴After a given time though, the gods turn away from this city, determining its fall.

-

✴They transfer kingship into a new city which becomes the new [city dynasty].

-

✴This pattern is repeated several times, until the SKL ends in the present or in the recent past.”

In this section, I shall attempt an analysis of:

-

✴the evolution of the USKL into the earliest recensions of the SKL; and

-

✴the subsequent development of the SKL over time.

SKL From Gushur to Lugalzagesi

Table 4 : Structural Evolution of the USKL

The first column of Table 4 contains a summary of the structure of the USKL between Gushur at Kish and Lugalzagesi at Uruk, as discussed above. This is the starting point for the other columns, which reflect the corresponding structure of the SKL, as represented by three reasonably complete examples:

-

✴recension 3, which can be placed securely in the ‘early’ group that begins with Gushur;

-

✴recension 9, which is broken at the start, but which is included here because it is the only recension other than recension 24 that contains a reasonably complete list of the Kish II kings; and

-

✴recension 24, because it:

-

•remains the most complete of the known Old Babylonian recensions; and

-

•can be placed securely in the ‘late’ group that begins with the AKL preface.

The most striking thing about this comparison is that a major structural change took place between the USKL and the early SKL recensions:

-

✴the single ‘Kish A’ list of the USKL was split into four distinct ‘city dynasties’ (labelled Kish I, Kish II, Kish IIIa and Kish IIIb (see below) by a number of ‘intervening’ dynasties;

-

✴the putative Uruk A* list of the USKL was apparently split into three (Uruk I, Uruk II and Uruk III) and included among these ‘intervening dynasties’; and

-

✴other ‘new’ ‘intervening dynasties’ (Ur I and II, Awan, Hamazi, Adab, Mari and Akshak) were added to the list.

As we shall see, in all of the post-USKL recensions that are unbroken at the bottom, the last named king ruled at Isin. Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2019, at p.21) therefore argued that these changes probably took place:

-

“It was [in the Isin period] that the SKL acquired its final form.”

This basic stability in the dynastic structure of the SKL recensions is clear from Table 4, albeit that, in the Isin period, signoficant change were made to the part of the list between Ku-Babu of Kish and Lugalzagesi of Uruk.

Queen Ku-Babu and the Kish III City Dynasty

Ku-Babu, the only queen recorded in any known recension of the SKL, was probably also recorded in the USKL immediately before Puzur-Sin and Ur-Zababa (as suggested in Table 4). Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below, at p. 53) observed that, in the SKL:

-

✴she sometimes (as in recension 3 in Table 4) similarly appears at the head of a single city dynasty (his Kish III), immediately before:

-

•Puzur-Sin and Ur-Zababa, who are now described as her son and grandson respectively; and

-

•the remaining Kishite kings; and

-

✴on other occasions (as in recensions 9 and 24 in Table 4), she appears alone in a single ‘city dynasty’ (still his Kish III), separated from her son and grandson and the other remaining Kishite kings (his Kish IV).

Jacobsen argued that Ku-Babu had originally had her own ‘city dynasty’, and that Akshak had subsequently been moved down the list so that she then joined the city dynasty of her descendants. However, Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 237 and note 17), who had the benefit of a larger number of exemplars, including the USKL, realised that the reverse must have been the case. He therefore suggested that:

-

“[Jacobsen’s] ‘Kish IV’ should rather be called Kish IIIb, since it was created through a later separation of Ku-Babu from her successors. The earliest [SKL recensions] still record a single Kish III [city dynasty], from Ku-Babu through to Nanne, [the last-named Kishite king in the SKL].

In other words:

-

✴in the early SKL recensions, Ku-Babu was immediately followed by Puzur-Sin, Ur-Zababa and the other remaining Kishite kings (as she had been in the USKL, but now explicitly identified as their mother of Puzur-Sin and the grandmother Ur-Zababa); while

-

✴subsequently (and for now-unknown reasons), Akshak was moved up the list to separate Ku-Babu (now in her own Kish IIIa dynasty) from her direct descendants and the other remaining Kishite kings (now in a separate Kish IIIb city dynasty).

Implications for the Relative Chronology of the SKL Recensions

Table 5: Chronological groups within the SKL corpus

Thus, it seems that two significant changes were made to the structure of the earliest SKL recensions:

-

✴the AKL preface was added (as discussed in an earlier section); and

-

✴the original single Kish III city dynasty was split into two (labelled Kish IIIa and Kish IIIb)

Table 5 summarises the results of the detailed analysis of all 24 of the known SKL recensions from Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming). Importantly, he established that the addition of the AKL preface was the later of these two developments, which allowed him to refine his model for their relative chronology, in which almost all of the 24 known recensions could be assigned to one of three main chronological groups.

Structure of the SKL From Lugalzagesi to the Kings of Isin

Table 6

The obvious point to make in the light of Table 6 is that the structure of the SKL between Lugalzagesi and Ur-Namma is essentially the same as that of the USKL. Thereafter, the compilers of the later recensions extended the USKL list by adding:

-

✴Shulgi and three more kings of Ur; and

-

✴formulae for the transfer of power from Ur to Isin, followed by records for:

-

•King Ishbi-Erra of Isin (who actually recaptured Ur after its fall to King Kindattu of Elam, an event that is unacknowledged in the SKL); and

-

•his successors at Isin.

The four SKL recensions summarised in Table 6 are the only ones that still preserve the name of the last king that they originally recorded:

-

✴Two of them (numbers 7 and 9) ended with Ur-Ninurta, the 6th of the 15 Isin kings, who is almost always described in the SKL as the son of the weather god, Ishkur. In these two recensions, his name is followed by a dedication:

-

“Ur-Ninurta, the son of Ishkur: may he have years of abundance, a good reign and a sweet life”, (see line 365 in this composite translation by ETCSL).

-

This suggests that these recensions were both compiled while Ur-Ninurta was still alive (albeit that the surviving ‘manuscripts‘ are later copies).

-

✴Recension 24 (= WB 444) certainly ended with Sin-magir, suggesting that it was compiled in either Sin-magir’s own reign or in that of his son and successor, Damiq-ilishu (the last of the Isin kings).

-

✴Recension 6 recorded the name of Damiq-ilishu himself, which suggests that it was originally compiled during or shortly after his reign.

Unsurprisingly, the last two of these recensions began with the AKL preface. However, the situation with the first two recensions is more interesting: as noted in Table 3, they both compiled in the second chronological phase:

-

✴after the splitting of the Kish III dynasties, so that Ku-Babu was separated from her son and grandson by the ‘intervening’ city dynasty of Akshak; but

-

✴before the addition of the AKL preface..

Thus the splitting of the Kish III dynasty took place either before or during Ur-Ninurta’s reign. (Since Ur-Ninurta is the first of the Isin kings who is not described in the SKL as the son of the king who preceded him, it seems to me that he is much more likely than his predecessors to have made this change.)

Dynastic Structure of the USKL and SKL Recensions: Conclusions

As Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below, at p. 13) observed, a comparison of the Old Babylonian recensions at his disposal showed:

-

“... extensive and detailed agreement between them in both form and content. [For example],:

-

✴the names of the rulers;

-

✴their mutual order;

-

✴the distribution of the names over the [city] dynasties; and

-

✴the order in which [these] dynasties appear;

-

are virtually the same in all the texts.”

As we have seen, he was aware of both:

-

✴the later change in the treatment of Ku-Babu and her city-dynasty; and

-

✴the still later addition of the AKL preface.

However, he reasonably concluded that these were second order changes that did not alter his basic conclusion. In his view:

-

“Agreement so extensive and detailed as this is unthinkable except between texts derived from a common source.”

Having produced a critical edition of the texts at his disposal, he further concluded (at pp. 140-1) that this common source was Utu-hegal (see above), who had rescued Uruk from the clutches of the Gutians. Of course, the discovery of the USKL text invalidated this hypothesis, since it then became clear that, in fact, the later USKL list was the immediate precursor of the Old Babylonian recensions. However, as we shall see, his recognition of Utu-hegal’s importance in the development of the SKL is still accepted by scholars.

Thorkild Jacobsen (referenced below, at pp. 165-6) also argued that. while the dynastic structure of the SKL is of negligible historical value in the pre-Sargonic period:

-

“..., the actual material from which it has been built up inspires more confidence. The material comes ... mainly from local lists of rulers ... and the author [of the SKL] has done little to them beyond cutting up a few of the longer ones and distributing through his compilation the smaller units thus obtained.”

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2019, at p. 40) commented that:

-

“One also looks in vain for any evidence of the local lists of rulers, such as the ones postulated by Jacobsen [here] as part of his efforts to demonstrate the historicity of the SKL”

Actually, this is not quite correct: the so-called Awan King List (see Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp, referenced below, at pp. 23-4) was almost certainly either compiled or up-dated by Puzur-Inshushinak (the 12th and last king in the list) in the early Ur III period. Its historical value cannot be dismissed, since it includes not only the clearly historical Puzur-Inshushinak himself but also (at number 8) Luhishan, son of Hisibrasini, who is also mentioned in one of Sargon’s inscriptions, Having said that, Steinkeller is certainly correct in his observation that:

-

“The choice of [the additional dynasties] and their rulers may have been guided by some considerations of propagandistic or conceptual nature, but those, if they existed, remain uncertain. This applies especially to the dynasties of Awan, Hamazi, Adab, Mari, and Akshak.”

(Sadly, the names of the three kings in the Awan dynasty in the SKL are not preserved in any of the surviving recensions, so it is impossible to know whether they came from Puzur-Inshushinak’s list.)

In conclusion, all we can really say about the way in which the dynastic structure of the SKL evolved over time is that:

-

✴at some time after the reign of Shulgi at Ur;

-

•the long Kish A in the USKL was cut into three shorter lists;

-

•the much shorter Uruk A” list was first significantly extended and then cut up into three parts;

-

•these Uruk I, Uruk II and Uruk III lists, along with other new ‘city dynasty’ lists (Ur I and II, Awan, Hamazi, Adab, Mari and Akshak) were introduced as ‘intervening dynasties’ separating Kish I, Kish II and Kish III from each other; and

-

✴in of after the reign of Ur-Ninurta at Isin, Akshak was moved up the list to separate Ku-Babu from her direct descendants and the other subsequent kings of Kish (creating the Kish IIIa and Kish IIIb city dynasties).

Comparison of Other Features of the SKL and USKL

‘Transfer of Kingship’ Formulae

As we have seen, the surviving USKL text contains three ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae:

-

✴In the first of these (at reverse column 2, lines 15’-18’), in the reign of the ‘Uruk A’ king Kuda:

-

•Uruk was struck with weapons.

-

•The kingship was carried to the ummanum (the Old Akkadian word for horde or army).

-

In most of the SKL recension (see Table 11), the Uruk IV king Kuda was followed by:

-

-two more Uruk IV kings (who were thus later additions); and

-

-a ‘summary of city dynasty’ formula.

-

Thereafter:

-

-Uruk was struck with weapons.

-

-The kingship was carried to ugnim gu-tu-um (where ugnim is the Sumerian equivalent of ummanum and gu-tu-um identifies the army in question as that of Gutium).

-

✴In the second (at reverse column 3, lines 12’-15’), when the Gutian Tirigan had ruled for only 40 days:

-

-The weapon was struck near (?) Adab (see Gösta Gabriel (referenced below, 2023, at p. 243 and notes 35-6).

-

-The kingship was carried to Uruk, [where] Utu-hegal was king.

-

In the SKL (332-5),

-

-Tirgan was followed by a ‘summary of city dynasty’ formula;

-

-The Gutian army (ugnim gu-tu-um) was struck with weapons.

-

-The kingship was carried to Uruk, [where] Utu-hegal was king.

-

✴In the third (at reverse column 5, lines 13’-18’, during the reign of the ‘Uruk B’ king Utu-hegal:

-

-Uruk was struck with weapons.

-

-The kingship was carried to Ur, [where] Ur-Namma ruled for 18 years.

-

In the SKL (at lines 335-343), Utu-hegal

-

-was given a ‘summary of city dynasty’ formula’ (even though this dynasty contained only a single king), following;

-

-Uruk was struck with weapons.

-

-The kingship was carried to Ur, [where] Ur-Namma ruled for 18 years.

Thus, the basic ‘transfer of kingship’ formulae were established by the time of Shulgi, albeit that the inclusion of ‘summary of city dynasty’ formulae was probably a subsequent development. Note, however, that there is some uncertainty, since the USKL text between Meshnune of Kish and Sargon of Akkad no longer survives.

Biographical Notes

Table 7

As Gianni Marchesi (referenced below, at p. 233) observed:

-

“Some manuscripts [of the SKL] add short biographical notes about particularly remarkable figures. Thus, we are told that certain personages, before becoming king, were, for instance, a shepherd, a fisherman, a smith, a fuller, a boatman, a leatherworker, a low-ranking priest etc. Even a female tavern-keeper, [Ku-Babu, mentioned above], seems to have exercised ‘kingship’, and not for a short time.”

He reproduced the most important of these notes (which relate to eight rulers) in an appendix (at pp. 238-42), and these are reproduced in Table 7.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 276) observed that, apart from the passage describing the ‘period of confusion’ at Akkad, the surviving USKL text contains no anecdotal information, which led him to the conclusion that all of the biographical notes in Table 7 were added subsequent to the compilation of the USKL. Actually, this is not immediately clear, since:

-

✴six of these rulers (Etana, Mesh-kiag-gasher, Enmerkar, Dumuzi, Gilgamesh and Ku-Babu) do not appear in the surviving USKL text; and

-

✴a seventh, Sargon, appears immediately after a break in the text.

In other words, only in the case of Enmebaragesi are we sure that the biographical note reflecting his victory over Elam was a later addition. However, I think that this case offers significant support for Steinkeller’ proposition, because:

-

✴(as we shall see) the traditions surrounding Enbaragesi were well known at Shulgi’s court (to the extent that a praise poem of Shulgi known as ‘Hymn O’ describes how Shulgi’s hero Gilgamesh liberated Uruk from his hegemony);

-

✴in one recension of the SKL (see Table 10), this tradition is reflected in an unprecedented second biographical note for Enmebaragesi;

-

✴Shulgi’s scribe seems to have added a patronymic to the name of the next Kish A king, Akka, describing him as the son of Enmebaragesi (see Table 2).

It seems to me that, since Enmebaragesi was not given a biographical note in the USKL, it is unlikely that anybody else was.

Biographical Note of Enmebaragesi

Although each of Enmebaragesi and his son Akka were given ‘superhuman’ reigns (600 and 1,500 years respectively in the USKL and 900 and 625 years respectively in the SKL), it is possible that Enmebaragesi, at least, was is based on a historical figure: as Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, at p. 5) observed:

-

“... the earliest known royal inscriptions are label inscriptions naming King Enmebaragesi of Kish.”

More specifically, he might be:

-

✴the Mebaragesi whose name appears (tout court) on a fragment of an alabaster bowl from Khafayah (ancient Tutub) in the Diyala valley (RIME 1: 7: 22: 1; CDLI. P431026); and/or

-

✴the Mebaragesi, king of Kish whose name appears on a similar fragment of unknown provenience (RIME 1: 7: 22: 2; CDLI, P431027).

His biographical note here is the first to record an apparently historical event, namely his conquest of Elam: although this event is not recorded in any other of our surviving sources, the ‘matter-of-fact’ nature of the note might well indicated that Enmebaragesi actually did defeat the Elamites (or, at least, that he claimed to have done so).

Biographical Note of Queen Ku-Babu

Ku-Babu, who was one of the last SKL rulers to be given a superhuman reign (albeit of a mere 100 years) is otherwise unknown: although she does feature in the so-called ‘Weidner Chronicle’ (at lines 42-5), this account might well have been inspired by her biographical note. Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2019, at p. 41 and note 72) argued that the ‘fantastic nature’ of this note suggests that it was ‘pure invention’. However, it seems to me that the compiler of the SKL is unlikely to have been the ‘inventor’ of a Kishite ruler who was:

-

✴the only queen named in any of the SKL recensions and a former innkeeper to boot; but

-

✴who nevertheless succeeded in consolidating ‘the foundations of Kish‘ (whatever thhis phrase actually means),

Rather, I suggest that she was more probably a historical figure whose story subsequently ‘grew in the telling’. (In his forthcoming book, Gösta Gabriel argues that she was remembered as the ruler whose ‘consolidation of Kish’ involved the restoration of dynastic succession there.)

Biographical Note of King Sargon of Akkad

Sargon is the only ruler listed in Table 7 who is clearly historical. Although almost nothing about his early life is known from sources that are independent of the SKL, we do know that:

-

✴he is never given a patronymic in his surviving royal inscriptions, so his father was almost certainly not a king, although the claim that he was the son of a gardener might be false;

-

✴there is no doubt that he became king of Akkad; and

-

✴although Akkad itself was documented before his accession, he may well have rebuilt it as his capital.

Thus, the main question about his biographical note is whether or not he started his career as the cup-bearer of King Ur-Zababa of Kish. Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2019, at p. 183 and note 468) argued that:

-

“... the proposition that Sargon was a cup-bearer of Ur-Zababa is invalidated by the SKL’s own evidence, namely, the fact that... [it names] five (or six) additional kings of Kish following Ur-Zababa.”

Indeed, as Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) points out, in the earliest versions of the SKL, Ur-Zababa and Sargon are separated by four Kish IIIa+b rulers, five kings of Akshak and King Lugalzagesi of Uruk (see Table 4). However, he argues that problems of this sort are the inevitable (if unintended) consequence of the introduction of narrative text from the literary tradition into an overtly diachronic document such as the SKL (as we saw, for example in the case of Dumuzi/Gilgamesh and Enmebaragesi).

In the case of Sargon and Ur-Zababa, the narrative in question was probably the so-called ‘Sumerian Sargon Legend’, which is known from two surviving fragmentary tablets (one from Uruk and the other from Nippur) that were published by Jerrold Cooper and Wolfgang Heimpel (referenced below: see also the on-line translation by ETCSL). As Cooper and Heimpel observed (at p. 68), the surviving text:

-

“... is full of grammatical and syntactic peculiarities that suggest a later Old Babylonian origin. ... But, this may just be a degenerate version of a text composed in the Ur III period; only the future discovery of more literary texts from that period and from other sites will enable us to know for certain.”

In other words, we cannot rule out the possibility that an earlier version of this text was available to the compilers of the SKL. In this legend, Sargon is the cup-bearer of Ur-Zababa at Kish during the reign of Lugalzagesi of Uruk: indeed, as Nshan Kesecker (referenced below, at p. 87) observed, the legend seems to imply that, at this time, Ur-Zababa ruled at Kish as a vassal of Lugalzagesi. If so, then the argument made by Piotr Steinkeller (above) would need to be inverted:

-

✴he argued that the ‘SKL’s own evidence invalidated the proposition that Sargon was a cup-bearer of Ur-Zababa; but

-

✴the evidence of ‘Sumerian Sargon Legend’ would instead invalidate the proposition that:

-

•the four Kish IIIa+b kings after Ur-Zababa;

-

•the five kings of Akshak;

-

•and Lugalzagesi;

-

were named in strict chronological order in the earliest versions of the SKL.

Indeed, the fact that the Akshak dynasty was subsequently moved up the list (thereby bringing Ur-Zababa, Lugalzagesi and Sargon somewhat closer together) provides further support for the proposition that, at least in Sumerian tradition, Ur-Zababa and his successors ruled Kish as vassals of Lugalzagesi.

Patronymics and Familial Dynasties

As set out in Table 7, some of the biographical notes in the SKL commented on the dynastic descent of their subjects:

-

✴ in the Uruk I city dynasty:

-

•Mesh-kiag-gasher was the son was Utu, the sun god;

-

•Enmerkar was the son of Mesh-kiag-gasher’ in the ; and

-

•Gilgamesh was the son of a spirit (lil2), albeit that he was known at Shulgi’s court as the son of the goddess Ninsun and her consort, Lugalbanda; and

-

✴Sargon, the founder of the Akkad city dynasty, was the son of a gardener.

Furthermore:

-

✴in the body of the SKL text, another 20 kings are described (like Enmerkar) as the son of the ruler named immediately above them; and

-

✴in BT 14 (= number 3 in Table 1 - mentioned above), which is the only recension to include familial dynasty formulae (within city dynasties), these formulae are given for at least six and possibly as many of eight) founders of ‘familial dynasties’. The usual pattern of these familial dynasty formulae can be exemplified by the one used for the Kish I king Enmebaragesi (see Table 8):

-

“Enmebaragesi, the one who overthrew the land of Elam with weapons, reigned 900 years. Akka, the son of Enmebaragesi, reigned 625 years. 1525 years was the divine allocation (of kingship) to the dynasty of Enmebaragesi”, (col. 2. lines 13-19, my translation into English of the German translation by Gösta Gabriel, forthcoming).

Kish I - III/V City Dynasties

Table 8

A significant proportion of the biographical and genealogical material in the SKL is concentrated in the Kishite city dynasties: more precisely, as set out in Table 8: more specifically, the records of these three city dynasties contain

-

✴3 of the 8 biographical notes;

-

✴at least 4 of the 6 certain familial dynasty formulae in BT 14; and

-

✴11 of the 22 kings with patronymics.

The case of these 11 kings with patronymics is interesting, since:

-

✴3 of them who were recorded in the USKL (Melim-Kish, Puzur-Sin and Ur-Zababa) were subsequently given patronymics; and:

-

✴another 3:

-

•Samug and Tizqar, the son and grandson of BAR.SAL-nuna; and

-

•Ushi-watar, the son of Zimudara;

-

were subsequent additions to the USKL list.

Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) reasonably argues that, when the Kish A list of the USKL was subsequently split into three parts:

-

✴patronymics were added to the names of at least 3 of the existing USKL kings (Melim-Kish, Puzur-Sin and Ur-Zababa); and

-

✴at least three new kings (Samug, Tizquar and Ushi-watar) were added to the USKL list as the sons of their respective predecessors.

These observations inform his suggested completion of the original Kish A list in the USKL.

Patronymics in the Kish A List of the USKL

Table 9

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 276) observed:

-

“Except for the sparse use of patronymics [ in the USKL], ... individual entries simply name the king and his regnal years.”

More specifically, as he pointed out, only three kings in the surviving text of this recension have patronymics:

-

✴two in the Kish A city dynasty;

-

•Akka; and

-

•Meshnume; and

-

✴Shar-kali-sharri of Akkad (see Table 11).

As discussed in my page on the USKL, it is usually assumed that the Kish A list was based on a king list that originated in Kish. Thus, since only these two 0f the 21 surviving kings in this list are given a patronymic, we might reasonably assume that these two patronymics were added by Shulgi’s scribe.

Akka is explicitly identified Enmebaragesi’s son in both the USKL and the Sumerian poem of ‘Gilgamesh and Akka’ (at line 1 and line 49, see Andrew George, referenced below, at pp.100-2). However:

-

✴in the poem, Gilgamesh defeats Akka; while

-

✴in Shulgi’s ‘Hymn O’, Gilgamesh defeats Enmebaragesi.

As Dina Katz (referenced below, at p. 14) observed, this:

-

“... raises the question whether Gilgamesh fought [two wars against Gilgamersh] or that we are dealing with two different traditions about one and the same war.”

She concluded (at p. 15) that these sources refer to the same war, and hat:

-

“Enmebaragesi's [more prestigious] name was deliberately inserted to replace Akka's [in ‘Hymn O’]: the [accounts in the poem] and the hymn are variants of one literary tradition.”

It is thus possible that Shulgis’ scribe gave Akka his patronymic in in an attempt to explain the existence of these two variants of this tradition.

The case of Meshnune is more complicated, not least because he is not included in any of the known SKL recensions (see Table 8). Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 278) offered a possible explanation for the his appearance in the USKL as the son of the Kishite king Nannee: he argued that Nanne and Meshnune:

-

“... almost certainly also ended up as the first two rulers of Ur II [in the SKL] ... It may further be speculated that they are also identical to [the first two rulers of Ur I in the SKL] ... Is it possible, therefore, that Nanne and Meshnune are, in fact Mesh-Ane-pada and Mesh-kiag-nuna of Ur, whom the USKL classified as Kishite rulers because Mesh-Ane-pada held the title [King of Kish]? If so, SKL’s decision to reclassify them as the rulers of Ur would be fully justified.”

The point here is that, by the time of the historical Mesh-Ane-pada, the title ‘king of Kish’ seems to have become an honorific title, with the connotation ‘king of the world’, probably indicating hegemony (or at least the claim of hegemony) over the land of Sumer. As it happens, two of inscriptions that mention Mesh-Ane-pada’s anepada survive:

-

✴a bead found at Mari names Mesh-Ane-pada as king of Ur and the son of Mes-KALAM-dug, king of Kish (RIME 1: 13: 5: 1); and

-

✴a clay sealing from Ur names Mesh-Ane-pada himself as king of Kish (RIME 1: 13: 5: 2).

It is therefore possible that Shulgis scribe:

-

✴had epigraphical evidence for Mesh-Ane-pada, king of Kish, and his son Mesh-kiag-nuna; and

-

✴abbreviated these two names as Nanne and Meshnune respectively and assumed that they had actually ruled at Kish.

This suggestion has been broadly accepted by (for example) Piotr Michalowski (referenced below, at pp. 159-60) and Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming). Thus, we should probably assume that:

-

✴Shulgi’s scribe added Nanne and Meshnune to the Kish A list of the USKL in error; and

-

✴the Ur I and the Ur II city dynasties were later additions to the USKL recension.

(An interestingly corollary is that Shulgi would presumably have been surprised the hear that he belonged to the ‘Ur III’ city dynasty.)

Uruk I City Dynasty

Table 10

As set out in Table 10, another significant proportion of the biographical and genealogical material in the SKL is concentrated in the early part of the Uruk I city dynasty. Of particular interest is the presence here unprecedented second biographical note for Enmebaragesi of Kish in the recension BT 14 (= my number 3 in Table 1). The textual context is as follows;

-

“Dumuzi, the fisherman whose city was Kuara, ruled for 100 years.

-

[Enmebarages note]

-

Gilgamesh, whose father was a spirit (lil2), the lord of Kulaba, was king. [He] ruled for 126 years”, ( col. iii, lines 6-15).

As Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) points out, this note has been variously translated as follows:

-

✴“He (i.e., Dumuzi) was taken as booty [i.e., taken captive] by the (single) hand of Enmebaragesi”, (see Jacob Klein, referenced below, at p. 78);

-

✴“He (i.e., Gilgamesh) took (away) the booty from the hands of Enmebarages”, (see Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, at pp. 241-2); and

-

✴“(Uruk) became booty [i.e., was sacked] through the hand of Enmebaragesi”, (my translation of the German of Gösta Gabriel, forthcoming).

Thus, although the precise translation is still debated, it certainly seems that the compiler of BT 14 was at pains to draw attention to the fact that Enmebaragesi had sacked Uruk, thereby causing an interregnum between Dumuzi and Gilgamesh, However, in so-doing, this compiler created an internal inconsistency, since:

-

✴the new note made Enmebaragesi a contemporary of Dumuzi and Gilgamesh; while

-

✴in the surrounding text, Enmebaragesi and Gilgamesh were separated by the reigns of:

-

•the Kish I king Akka (625 years); and

-

•the Uruk I kings:

-

-Mesh-kiag-gasher and Enmerkar (a total of 745 years);

-

-Lugalbanda (1200 years); and

-

-Dumuzi (100 years).

Given the fact that, in the USKL, the text between Meshnune of Kish and Sargon of Akkad is now missing, we do not know whether any or all of these mythical Uruk I kings were named there (with or without patronymics or biographical notes). Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) argues that the first 7 were all later additions. However, Ludek Vacin, referenced below, at p. 224) argued that, although Uruk is not mentioned in the surviving USKL text until the Uruk IV king Kuda (see Table 11):

-

“... it can be reasonably assumed that [the Uruk I dynasty] was there, because its [significance] for Ur III ideology was enormous. In the [SKL], one encounters the Uruk I dynasty king Lugalbanda, followed by Dumuzi and Gilgamesh. The structure of this section coincides with the mythical dimension of Shulgi’s royal ideology, permeating his hymnal compositions with their intricate semi-mythological literary fabric and constituting the basis of his royal as well as divine authority”.

He noted (at p. 16) that Enmerkar does not feature in Shulgi’s hymns (and, for that matter, neither does Enmerkar’s father, Mesh-kiag-gasher), but he argued (at p. 224 again) that Shulgi’s:

-

“... relationship to Gilgamesh is [stressed in these hymns], especially in hymn Shulgi O, which contains (inter alia) the following reference to the Sumerian King List in Shulgi’s address to Gilgamesh:

-

‘[You drew your weapons against the house of Kish.

-

You took captive (!) there its seven heroes.

-

As on a snake, you set foot on the head of Enmebaragesi, king of Kish.

-

You brought kingship from Kish to Uruk.

-

(Thus) he [i.e. Shulgi] extolled the one born in Kulaba [i.e., Gilganesh] …’, (lines 56-61).”

In my page on the USKL, I similarly argue that Gilgamesh must have appeared in the USKL at some point between Meshnune of Kish and Sargon of Akkad, thereby violating what Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2003, at p. 275) characterised as the:

-

“... diachronic principle to which the USKL otherwise religiously subscribes.”

-

However, Gösta Gabriel (as above) is certainly correct that there cannot have been many of these early kings in a list of no more than 9 pre-Sargonic kings of Uruk. In short, it is likely that almost all of the SKL text from Mesh-kiag-gasher to Gilgamesh (including the ‘fact’ that Gilgamesh’ father was a spirit and that he was succeeded at Uruk by his son and grandson) was a later addition to the original USKL text.

Akkad and Uruk IV

Table 11

As set out in Table 11, the last of the 6 certain familial dynasty formulae in BT 14 was devoted to the dynasty of Sargon at Akkad. The relevant passage survives as follows:

-

“In Akkad, Sargon: his father was a gardener.

-

[Text broken]

-

[Naram-Sin] ruled for [x] years.

-

Shar-kali sharri, the son of Naram-Sin, ruled for 24 years.

-

[x] years [was the divine allocation (the royal rule)] of (the dynasty of) Sargon”, (col. vii, line 12” - col. viii, line 6’, my translation of the German of Gösta Gabriel, forthcoming).

The full text of the biographical note given to Sargon in the SKL (see Table 7) was:

-

“Sargon, whose father was a gardener, the cup-bearer of (king) Ur-Zababa [of Kish], <the one who became> the king of Akkad, the one who built Akkad.”

Interestingly, Shar-kali sharri is the only one of Sargon’s direct descendants who had already had a patronymic in the USKL.

The subsequent description of the ‘period of confusion’ at Akkad certainly originated in the USKL, and it is likely that my Lacuna 4 contained the names of:

-

✴Dudu and Shu-Turul, the last two Akkadian kings in the SKL; and

-

✴Ur-nigin and Ur-gigir, the first two Uruk Iv kings in the SKL.

However, it is impossible to determine whether either Shu-Turul of Akkad or Ur-gigir of Uruk was given a patronymic in the USKL.

Evolution of the SKL: Analysis and Conclusions

Legitimisation of the Isin Kings in the SKL

Some 20 years before the publication of the USKL, Piotr Michalowski (referenced below, 1983, at p. 240) observed that:

“It has often been stated that [the SKL] contains a fiction, a notion that Sumer and Akkad were always ruled by one dynasty at a time.”

As we have seen, this fiction was expressed in the SKL as a list of successive dynasties that dated back far into the mythical past, with the transfer of the kingship from one dynasty to the next expressed formulaically. Michalowski noted that, at his time of writing:

“The most detailed account of the propagandistic nature of the King List was offered by J. J. Finkelstein [referenced below], who ... interpreted [the SKL] as an expression of the idea of centralisation of power [in Mesopotamia] in the hands of one dynasty, ruling from one city, an idea that ... was ultimately realised as a legitimation of the Isin dynasty.”

He pointed out (at p. 242) that Ishbi-Erra, the founder of the dynasty, had:

“... attained high status and, eventually, control of Isin only through his service to the [last] kings of Ur. Briefly stated, I should like to propose that ... [the Isin kings’] claim to legitimacy was] the central issue of the [SKL]. The fiction that each city of Mesopotamia in turn held the ... [kingship of the entire region] served to bolster their claims of hegemony over all the territories that had once been under the rule of the Ur III dynasty. In this sense the [SKL] complements the evidence of:

the lists that enumerate the Ur and Isin kings as if they constituted one unbroken chain of rulers [see, for example, Andrew George, referenced below, at pp. 206-7)];

the liturgical composition [known as the ‘Lament for Damu’ (AO 5374, Musée du Louvre)], which lists the kings of these dynasties as incarnations of the god Damu; [and]

... the perpetuation of particular forms of ‘royal hymns’ by the Isin kings [using Ur III models].

This conscious attempt to link the Isin dynasty with the Ur III kings was most dramatically realised in [the Old Babylonian ‘Lament over the Destruction of Sumer and Ur’], a literary text that exploited the fall of Ur.”

He drew attention to one particular passage of this lament, in which Enlil responded to the lament of Nanna, the god of Ur:

“... why do you concern yourself with crying? The judgment uttered by the assembly [of the gods] cannot be reversed. The word of An and Enlil knows no overturning. Ur was indeed given kingship, but it was not given an eternal reign. From time immemorial, since the Land was founded, ... who has ever seen a reign of kingship that would [last] for ever? The reign of [the Ur III kings] had been long indeed, but had to exhaust itself”, (lines 365-9).

As Michalowski pointed out, this lament and the SKL:

“... reflect the same ideology: Isin is [next] in line to hegemony, and that is simply the way things are.”

More recently, Niek Veldhuis (referenced below, at p. 393) placed the compilation of the SKL at Isin in the context of:

“The creation of the new lexical corpus in the early Old Babylonian period, [which] may be understood, paradoxically, as an attempt to preserve and guard traditional knowledge of Sumerian. [Although Sumerian] was a dead language by this time, [it was still] of prime importance for political ideology [and] the language of royal inscriptions and royal praise songs. The [SKL], backed by a variety of Sumerian legendary texts and songs, explains how, since antediluvian times, there had always been one king and one royal city reigning over all of Babylonia. This view implied that there were no separate local histories; all city-states were Babylonian, or, more properly of ‘Sumer and Akkad’, so that, [for example]:

Enmerkar and Gilgamesh of Uruk;

Sargon of Akkad; and

Shulgi of Ur;

could all be celebrated as great predecessors [of the Isin kings].”

Jerrold Cooper (referenced below, at p. 12) developed this point as follows:

“Niek Veldhuis [as above] has written about the Sumerian 'invented tradition’, the fact that the scribal curriculum we know from ca. 1800 BC ... can be read through the tense of the so-called Sumerian King List, a text promulgated under Shulgi, that asserts, quite fallaciously, that from antediluvian times onward there had been only one legitimate king of Babylonia at a time, and that this one kingship circulated among different cities.”

However, as we have seen, the insertion of ‘intervening dynasties’ into what was probably originally an unbroken list of Kishite kings (who were, as a consequence, split up into three or four separate dynasties) was the work if the Isin kings. In other words:

while Shulgi, like the Isin kings, was of questionable legitimacy and probably did develop earlier Sumerian and Akkadian king lists in order to portray himself as the natural successor of men like Gilgamesh of Uruk and Sargon of Akkad (as I discuss in the following pages);

there is no evidence in the surviving USKL text to support Cooper’s assertion that Shulgi claimed in this recension that, since time time immemorial:

“... there had been only one legitimate king of Babylonia at a time, and that this one kingship circulated among different cities.”

Unfortunately, much of the ‘received wisdom’ relating to the SKL was developed long before:

-

✴the first publication of the USKL by Piotr Steinkeller in 2003; and

-

✴the critical edition of the modern corpus (26 recensions, including the USKL) and the accompanying analysis of Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming).

Thus, Piotr Michalowski (referenced below, 1983, at p. 238), for example. observed that the SKL:

-

“... exhibits a structure which is difficult to define. It is in many ways a list but, although it is constructed by means of an unrelenting repetition of formulae, it cannot be easily classified as a chronicle, as an annal, or as any of the other of the traditionally designated forms of elementary historical narratives.”

He noted (at p. 240) that, at his time of writing:

-

“The most detailed account of the propagandistic nature of the [SKL] was offered by J. J. Finkelstein [referenced below], who ... interpreted [it] as an expression of the idea of centralisation of power in the hands of one dynasty, ruling from one city, an idea that ... was ultimately realised as a legitimation of the Isin dynasty.”

He added (at pp. 242-3) that:

-

“The meaning of the text is not revealed by any narrative episodes but through the cumulative effect of the structure of the composition. The ending of the text is simply the present: the Isin kings.”

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below 2019) at p. 194) proceeded with his analysis by addressing the question of:

“... when and why was the fatalistic vision of history as a chain of recurring cycles imposed on the king list? In all probability, this happened not earlier than in Isin times (ca. 2000‒1850 BC), mainly as a response to the traumatic experiences that the fall of Ur had visited upon Babylonia. Here it should be realised that the demise of the House of Ur was much more complete (and probably also even more unexpected) than that of the Sargonic empire. It was very likely that this horrific event that called for a radical re-evaluation and re-arrangement of the existing symbols.”

At this point, he quoted from his earlier paper (Steinkeller, 2003, at pp. 285-6):

“A [putative] linear sequencing of events did not make sense any longer: while the fall of the suspect Akkad could be comprehended, no existing explanation might have accounted for the demise of the seemingly perfect Ur. And so, history had to be given a cyclical pattern, in which kingship circulates among a number of cities in a fairly regular sequence, never staying in one place for long”.

In short, in my view:

there is no evidence to suggest that the structure of the USKL was shaped by the concept of a single, god-given ‘kingship’ that, since time immemorial, had passed between cities of Mesopotamia and its neighbours in a relentless cycle of rises to and falls from power; and

while the structure of the SKL might reflect a conscious desire to articulate this clearly fictitious concept, it is more probably the unintended consequence of changes that were subsequently made to the USKL for other reasons.

References

Gabriel, G. I.,"The ‘Prehistory’ of the Sumerian King List and Its Narrative Residue", in:

Konstantopoulos G. and Helle S., “The Shape of Stories”, (2023) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 234-57

Osterman J., “From ki-en-gi to Šumerum: How Sumer was Created ?”, Radovi HSP, 54:3 (2022) at pp. 39-72

George A., “The Epic of Gilgamesh: The Babylonian Epic Poem and Other Texts in Akkadian and Sumerian (2nd Edition)”, (2020) London

Steinkeller P., “History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays”, (2019) Boston and Berlin

Beaulieu P.-A., “A History of Babylon (2200 BC - AD 75)”, (2018) Hoboken, NJ

Kesecker N. T., “Lugalzagesi: the First Emperor of Mesopotamia?”, Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 12:1 (2018) 76-95

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I., “Part I: Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol. 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 1-130

Michalowski P., “Sumerian King List”, in:

Bagnal R. S. et al. (editors), “The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, First Edition”, (2013), at pp. 6448-9

Vacin L., “Šulgi of Ur: Life, Deeds, Ideology and Legacy of a Mesopotamian Ruler As Reflected Primarily in Literary Texts”, (2011), thesis of the School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London)

Marchesi G., “The Sumerian King List and the Early History of Mesopotamia”, in:

Biga M. G. and Liverani M. (editors.), “Ana Turri Gimilli: Studi Dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer da Amici e Allievi”, (2010) Rome, at pp 231-48

Frayne D. R. , “The Zagros Campaigns of the Ur III Kings”, Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies, 3 (2008) 33-56

Klein J., “The Brockmon Collection Duplicate of the Sumerian King List (BT 14)”, in:

Michalowski P. (editor), “On the Third Dynasty of Ur: Studies in Honor of Marcel Sigrist”, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Supplemental Series 1, (2008) at pp. 77–9

Glassner J.-J., “Mesopotamian Chronicles”, (2004) Atlanta GA

Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-292

Frayne D. R., “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Early Periods, Vol. 2: Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2334–2113 BC)”, (1993) Toronto, Buffalo and London

Katz D., “Gilgamesh and Akka: Library of Oriental Texts, Vol. 1”, (1993) Groningen

Cooper J. S. and Heimpel W., “The Sumerian Sargon Legend”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 103:1 (1983) 67-82

Michalowski P., “History as Charter: Some Observations on the Sumerian King List”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 103:1 (1983) 237-48

Finkelstein, J. J., "Early Mesopotamia (2500-1000 BC)”, in:

Lasswell H. D. et al. (editors), “Propaganda and Communication in World History: The Symbolic Instrument in Early Times”, (1979) Honolulu, at pp. 60-3

Jacobsen T., “The Sumerian King List”, (1939) Chicago IL

Langdon S. H., “The H. Weld-Blundell Collection in the Ashmolean Museum: Vol. II: Historical Inscriptions, Containing Principally the Chronological Prism (WB. 444)”, (1923) London

Foreign Wars (3rd century BC)

Home