Empires of Mesopotamia:

Kingdom of Kish in the Presargonic Period

Empires of Mesopotamia:

Kingdom of Kish in the Presargonic Period

Interestingly:

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2024):

argued (at p. 23) that the reign of Ur-Nanshe (the first independent ruler of Lagash) was roughly contemporaneous with the Fara tablets, (and hence with the ‘Kiengi League’); and

suggested (at p. 14) that Enna-il could have ruled at Kish either:

at the time of the ‘Kiengi League’; or.

during the reign of Eanatum (the grandson of Ur-Nanshe, wh is known to have used the title ‘king of Kish - see the following page); and

Gianni Marchesi (referenced below, 2015):

argued that Enna-il:

“... was probably the last great king of Kish proper”, (see note 19, at p. 140); and

reigned at Kish in the latter part of the reign of of Ur-Nanshe at Lagash and continued into the reign of his son, Akurgal (see Table 1.2, at p. 142).

Thus, it is at least possible that:

Enna-il ruled at Kish at the time of the formation of the ‘Kiengi League’;

he was defeated in or after the engagement recorded in the Fara texts discussed above; and

this explains why (for example) Ur-Nanshe was able to establish his independent rule at Lagash.

✴

Kings of Kish in the Presargonic Period

As Aage Westenholz (referenced below, 2020, at p. 695 observed, the title lugal kish (king of Kish):

“... developed through time, from meaning:

✴quite literally ‘king of Kish’ [for most or not all of the Early Dynastic Period, as discussed in the previous page]; to

✴‘king of the whole world’ ... possibly even as early as Sargon of Akkad.”

The present page deals with the use of this title in intermediate ‘Presargonic Period’, when a small number of rulers whose capitals were not at Kish nevertheless included the title lugal Kish in their royal titulary.

Meskalamdu and Mesanepada: Kings of Ur and of Kish

Meskalamdu

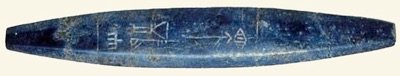

Lapis lazuli bead (RIME 1.13.5.1, P431203) from Mari

Now in the National Museum, Damascus: image from Jean-Claude Margueron (referenced below, at p. 143)

The inscription (P247679) on a seal from the royal cemetery of Ur that is now in the British Museum (exhibit BM 122536) reads: ‘mes-kalam-du10 lugal’, (Meskalamdu, the king). Given the find spot, we might reasonably assume that Meskalamdu was the king of Ur. However the inscription (RIME 1.13.5.1, P431203) on an eight-sided bead from Mari (illustrated above and discussed below) reads:

“For [DN]: Mesanepada, king of Ur, the son of Meskalamdu, king of Kish, has consecrated (this bead)”, (translation from Jean-Claude Margueron (referenced below, at p. 143).

Thus, Meskalamdu seems to provide us with an example of a Presargonic Sumerian ruler who used the title ‘king of Kish’, despite the fact that his capital was located at somewhere other than Kish (i.e., in this case, at Ur).

Mesanepada

Turning now to Mesanepada himself, who is named as the king of Ur on this bead from Mari illustrated above, which was found in a jar together with other precious objects in the ‘sacred precinct’ of the pre-Sargonic palace there. The excavators characterised these objects as the ‘treasure of Ur’ and speculated that this ‘treasure’ had been a royal gift from Ur. However, it has subsequently emerged that the objects themselves are quite disparate, and the circumstances in which this particular object found its way (presumably from Ur) to Mari are actually unknown. Furthermore, there is some doubt about the identity of the god to whom Mesanepada dedicated it: for example:

✴Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, RIME 1.13.5.1, at p. 392) gave ‘an lugal-[ni]’ (to the god An, his lord); while

✴Glenn Magid (referenced below, at p. 10) and the entry at CDLI, P431203 give ‘dlugal-kalam’ (to the god Lugalkalam).

Thus, the only thing that we can take from the inscription on the bead is that Mesanepada used the title ‘king of Ur’ at a time when his father, Meskalamdu, (who was presumably still alive) used the title ‘king of Kish’.

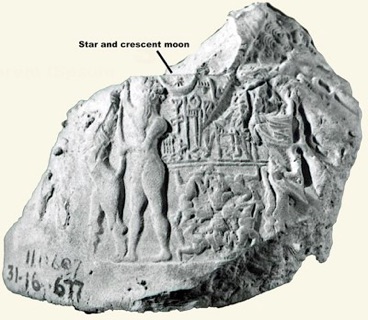

Seal of Mesanepada (RIME 1.13.5.2, P431204) from Ur

Now in the Penn Museum (Sealing 31-16-677), image from museum website

A second royal inscription of Mesanepada (RIME 1.13.5.2, P431204), which is on a clay sealing from Ur (illustrated above) that came from one of three ‘seal impression strata’ in the levels above the so-called ‘Royal Cemetery’ at Ur (see Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, 2011, at p. 64), reads

“Mesanepada, King of Kish, dam nu-gig (husband of the nu-gig)”.

Glenn Magid (referenced below, at p. 6) observed that nugig could have been either:

✴the name of one of Mesanepada’s actual wives; or

✴the name of:

“... a well-known type of priestess. If so, then [this inscription] would constitute the earliest evidence for a ritual that is otherwise attested only later in Mesopotamian history: the annual ‘sacred marriage’ between the king and a goddess (embodied in the person of her priestess).”

Petr Charvát, referenced below, 2017, at p. 196 and note 37) translated nugig as ‘the Lofty One’, and observed that this could have been either a reference to the ‘nugig priestess’ (a priestess of Inanna) or an epithet Inanna herself. Pirjo Lapinkivi (referenced below, at pp. 18-20) observed that:

“Enmerkar, the legendary king of Uruk, was the earliest Sumerian ruler who called himself Inanna’s husband. ... Even if the evidence [of the Enmerkar legend] is questionable, there are other sources that indicate an affectionate relationship between the Sumerian ruler and the goddess of love as early as the ED II period: [for example], there is a seal impression of Mesanepada ... [that] declares [him] to be ‘the husband of the nu-gig’. The term nu-gig probably refers to the common epithet of Inanna ... The impression also has designs of a star and a crescent moon, which were both common symbols for Inanna in her astral aspect (the planet Venus and the morning and evening star).”

As we shall see, this is the earliest of a series of indications that the title ‘king of Kish’ might have been in the gift of the goddess Inanna (a suggestion first made by Tohru Maeda (referenced below, 1981, at pp. 7-9).

Dynasty of Meskalamdu and Mesanepada

As Douglas Frayne (reference below, 2008, at p. 377) observed:

“The SKL assigns four kings to its Ur I dynasty: Mesanepada, Meskiagnanna, Elulu, and Balulu. In addition, Mesanepada and Meskiagnanna appear [as father and son] in the [broadly contemporary] ‘Tummal Chronicle’.

Frayne also argued (at p. 381) that the ‘Ur II dynasty’, which was originally proposed in 1939 by Thorkild Jacobsen, (referenced below, at pp. 172-6), has been shown by subsequently-discovered recensions of the SKL to be:

“... a phantom, and is not recorded in the SKL.”

In fact, the analysis by Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming) of the 24 SKL recensions that make up the current corpus suggests that the composite text should include:

✴four Ur I kings (CDLI: P479895’; lines 133-144):

•Mesanepada (line 135);

•Meskiagnanna, the son of Mesanepada (lines 137-8);

•Elulu (line 141); and

•Balulu (line 142; and

✴5 or 6 Ur II kings, albeit that only two names survive (in these in only two recensions) (CDLI: P479895’; lines 192-202):

•Nanni (line 193); and

•Meskiagnanna, the son of Nanni (line 196).

Moreover, these two father and son pairs appear in the ‘Tummal Chronicle’:

✴Mesanepada and Meskiagnuna, the son of Mesanepada. (at lines 7-11); and

✴Nanni and Meskiagnanna, the son of Nanni, (at lines 17-21).

Since this is hardly likely to be a coincidence, we might reasonably assume that, at least by the time of the Isin kings, these two father and son pairs of kings of Ur featured in Sumerian tradition.

As we have seen, Mesanepada is a securely historical figure, as is his father, Meskalamdu, who does not appear in the SKL. It is also possible that the name Meskiagnanna/ Meskiagnuna was recorded in adamaged inscription on a bowl fragment that was discovered in the ‘loose soil’ above the ‘Royal Cemetery’ refers to a king of Ur:

“[... Mes-ki-á]g-nun, king of Ur: Gan-samana, his wife, dedicated (this bowl)”, RIME 1:13:8:1; P222843).

Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 2008, at p. 403 and Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, 2015, p. 144, Uruk entry 2) accepted this as a plausible reconstruction, although nothing in this inscription suggests that this putative King Meskiagnun of Ur was a son of Mesanepada: Gianni Marchesi (referenced below, 2004, note 97, at p, 168) argued that:

“... on an epigraphic basis, this king of Ur seems] to be an earlier ruler than Mesanepada ...”

Fortunately, the publication by Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003) of the earliest-known recension of the SKL (which dates to the Ur III period and is therefore referred to as the USKL) allows us to take this analysis further.

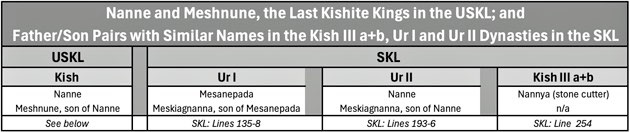

See Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2003, at p. 271, lines iii: 11-15) for Nanne and Meshnune in the USKL; and

CDLI: P479895 for the entries for father/son pairs with similar names in the SKL

Unfortunately, the USKL text is only known from a single broken tablet of unknown provenance that preserves only about half of it (see CDLI: P283804), but the surviving last line indicated that the list itself was compiled for Shulgi, the second of the Ur III kings. It is not known whether the original list named any kings of Ur other than Shulgi’s father, Ur-Namma, the founder of what we know as the Ur III dynasty. However, Piotr Steinkeller (as above) was able to establish (at p. 274) that it began with an unbroken list of about 30 kings of Kish, the last of whom are named in the surviving text as:

✴Nanne; and

✴Meshnune, the son of Nanne (as set out in the first column of the table above).

Steinkeller observed (at p. 278) that the father/son pair:

“... appears to have had a double (or even a triple) life in the (later ) SKL, [which was derived from the USKL]”;

which prompted him to ask rhetorically:

“Is it possible that [the USKL kings] Nanne and Meshnune are in fact Mesanepada and Meskiagnuna of Ur, whom the USKL classified as Kishite rulers because Mesanepada held the title of [king of Kish]? If so, [their reclassification in the SKL as Ur I kings] would be fully justified.”

In other words, is possible that the USKL scribe:

✴had epigraphical evidence for Mesanepada, king of Kish, and his son Meskiagnuna; and

✴abbreviated these two names as Nanne and Meshnune respectively and assumed that they had actually ruled at Kish.

Piotr Steinkeller summarised (at p. 278) as follows:

“Is it possible ... that Nanne and Meshnune [of the USKL] are, in fact Mesanepada and Meskiagnuna of Ur, whom [the author of the original SKL] classified as Kishite rulers because Mesanepada held the title of [king of Kish]. If so, then [SKL author’s] decision would be fully justified.”

As Gianni Marchesi (referenced below, 2004, note 97, at p, 168) observed:

“Apparently, the author of the SKL was unaware of the actual sequence of the ED kings of Ur and ordered them at random.”

This suggestion has been broadly accepted by (for example) Piotr Michalowski (referenced below, at pp. 159-60) and Gösta Gabriel (forthcoming).

This leaves us with what Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, at p. 377) characterised as ‘a native dynasty at Ur’ that began with Meskalamdu and his son, Mesanepada. As it happens, we also know of an ‘historical’ son of Mesanepada: surviving royal inscriptions of A’anepada name him as:

✴A’anepada, king of Ur (RIME 1:13:6:1; P431206); and

✴A’anepada, king of Ur, son of Mesanepada, king of Ur (RIME 1:13:6:3; P431208).

Meskalamdu and Mesanepada: Kings of Ur and of Kish: Conclusions

We can now attempt to hypothesise on the significance of the fact that each of Meskalamdu and Mesanepada used the titles king of Ur and king of Kish, starting with the fact that:

✴as far as we know, neither of them ever held both titles at the same time; and

✴in the inscription on the bead from Mari (in which both men are named), Mesanepada is described as ‘king of Ur, the son of Meskalamdu, king of Kish’.

Gianni Marchesi (referenced below, 2015, at p. 145, Uruk entry 6) argued that, in this period, Meskalamdu (and subsequently his son) used the title ‘king of Kish’ to signify that he actually ruled at both Uruk and Ur (rather than at Kish itself). He based this on the fact that, as he noted (at pp. 144-5, Uruk entry 4), an earlier ruler named Lugalnamnirshumma had been described as ‘king of Kish’ in the inscription (RIME 1.8.2.1: P462183) on a votive spear-head that had been found on the site of the original temple of Ningirsu at Girsu, the ‘religious capital’ of Lagash. On his understanding of the archeological context in which this spearhead and a votive object dedicated by a’the chief lamentation priest of Uruk’ had been found, he concluded that:

✴Lugalnamnirshumma’s reign had been roughly contemporary with those of Meskalamdu and Mesanepada; and

✴at this time, for whatever reason, ‘king of Kish’ meant ‘king of Uruk’.

He therefore asserted (at p. 145, Uruk entry 6) that, on Mesanepada’s seal (above):

“... [Meskalamdu] is referred to as ‘king of Kish’, that is, king of Uruk. It is also worth noting that, in the same inscription, [Mesanepada] calls himself ‘king of Ur’ ... Presumably, after occupying the more prestigious post of king of Uruk, [Meskalamdu] gave Ur to his son Mes’anepadda to rule. Upon the father’s death, [Mesanepada] ascended the throne of Uruk, as is revealed by the title ‘king of Kish’ on his seal.”

Unfortunately, as Sébastien Rey (referenced below, at p. 209) observed:

✴a number of scholars have been misled by an early, flawed description of the find-spot of this spear-head of ugalnamnirshumma within the complex archeological site of the temple at Girsu; and

✴the problems that this has raised have been:

“... compounded by the theory that kings of Uruk might perhaps have assumed the ‘catch-all’ title king of Kish ...”

He pointed out (at p. 210) that, once it is understood that the spear-head of Lugalnamnirshum had been buried in the same archeological context as the famous mace of Mesalim, it becomes clear that Lugalnamnirshum was:

“... one of Mesalim of Kish’s successors, and, therefore, in all likelihood, another foreign overlord of Girsu [and Lagash].”

Thus, there is no particular reason to assume that Lugalnamnirshum had ruled at Uruk, thereby undermining Marchesi’s hypothesis that, by extension, Meskalamdu and then Mesanepada used the title of king of Kish to signify that he ruled at both Ur and Uruk.

It is, of course, possible, that:

✴at some point in his reign, Meskalamdu retired in order to allow Mesanepada to rule at Ur, at which point he himself adopted the honorary title of ‘king of Kish’; and

✴Mesanepada subsequently followed his example by retiring to make way for one of his sons.

However, we have no hard evidence that this was the case:

✴as we have seen, although a king of Ur named Meskiagnuna is apparently recorded in a surviving royal inscription, he is not given a patronymic and he might well have ruled at Ur before Mesanepada; and

✴the only known son and successor of Mesanepada, A’anepada, is referred to in his surviving inscriptions only as:

•A’anepada, king of Ur (RIME 1:13:6:1; P431206); or

•A’anepada, king of Ur, son of Mesanepada, king of Ur (RIME 1:13:6:3; P431208).

Furthermore, this second inscription suggests that Mesanepada was using the title ‘king of Ur’ at the time of his death and of A’anepada’s accession. In short, the most likely scenario is that:

✴Meskalamdu actually captured Kish, at which point:

•he became ‘king of Kish’; and

•Mesanepada adopted the ‘lesser’ title ‘king of Ur’; and

✴on Meskalamdu’s death, Mesanepada became king of Kish, but subsequently lost control of that city, at which point he reverted to the ‘king of Ur’, the title that he duly passed on to his son, A’anepada.

Eanatum, Ensi of Lagash and King of Kish

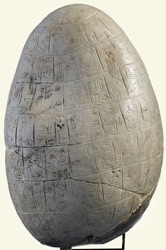

Eanatum Boulder, from Girsu (now in the Musée du Louvre: AO 2677)

Image from the museum website

As discussed above, Aage Westenholz (referenced below, 2020, at p. 697) argued that, even if the prisoners listed on the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ at Kish (many of whom came from distant localities) could be shown to have been taken in battle, this would :

“... scarcely [prove] the existence of a territorial state in the north, [centred on Kish, as hypothesised by Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013)], any more than [the evidence for] Eanatum’s campaigns ... [against enemies from distant cities] prove the existence of a territorial state in the south, centred on Lagash.”

This is a reference to a campaign recorded of the so-called ‘Eanatum Boulder’ (illustrated above), in which we read that:

“Because Inanna so loved Eanatum, the ensi (ruler) of Lagash, she gave him nam-luga[ (the kingship) of Kish, together with nam-ensi2 (the rulership) of Lagash:

✴Elam trembled before him (and) he sent the Elamite back to his land.

✴Kish trembled before him.

✴He sent [Zuzu], the king of Akshak, back to his land.

Eanatum, the ruler of Lagash, who subjugates foreign lands for [the god] Ningirsu, defeated:

✴Elam, Subartu [= Shubur, Assur, Assyria ] and Uru at the Asuhur [canal (?) ... ; and]

✴Kish, Akshak and Mari at the Antasura of Ningirsu”, (RIME 1.9.3.5, P431079, lines 98-126).

(See Map 3 above for Assur/ Subartu, Akshak and Mari.). Steinkeller had argued (at p. 150) that, since Eanatum’s battle(s) were explicitly fought near Lagash, they had been largely defensive, but Westenholz countered (at p. 688) that:

“... Eanatum surely did more than merely seeing his enemies off:

✴Zuzu of Akshak was pursued all the way to the safety of his own city, soundly beaten.

✴Eanatum ... claimed to be ‘king of Kish’, and a fragment of an inscription of his has actually been excavated there, as if to prove the veracity of that claim.

Even so, his dominion over the north was probably quite short-lived.”

(The inscription to which Westenholz referred is in the Ashmolean Museum (Ashm, 1930-204; P221781): Westenholz read ‘[é-an-na-túm / …] / [dumu] a-ku[r-gal’ in the broken passage, and identified this as Eanatum, son of Akurgal, ensi of Lagash).

References

Postgate J. N., “City of Culture 2600 BC: Early Mesopotamian History and Archaeology at Abu Salabikh”, (2024) Oxford

Rey S., “The Temple of Ningirsu: the Culture of the Sacred in Mesopotamia”, (2024) University Park, PA

Steinkeller P., “Campaign of Southern City-States against Kiš as Documented in the ED IIIa Sources from Šuruppak (Fara)”, Journal of Cuneiform Studies, 76 (2024) 3-26

Westenholz A., “Was Kish the Center of a Territorial State in the Third Millennium?—and Other Thorny Questions”, in:

Arkhipov I. et al. (editors), “The Third Millennium: Studies in Early Mesopotamia and Syria in Honor of Walter Sommerfeld and Manfred Krebernik”, (2020) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 686-715

Charvát P., “The Origins of the LUGAL Office”, in

Drewnowska O. and Sandowicz M. (editors), “Fortune and Misfortune in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 60th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at, Warsaw, 21–25 July 2014”, (2017) Winona Lake, IN, at pp. 193-200

Rey S., “The Temple of Ningirsu: the Culture of the Sacred in Mesopotamia”, (2024) University Park, PA

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I., “Part I: Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol. 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 1-130

Marchesi G., “The Historical Framework (Chapter 2)” and “The Inscriptions on Royal Statues (Chapter 4)”, in:

Marchesi G. and Marchetti N., “Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia”, (2011) Winona Lake, IN, at pp. 97-128 and pp. 155-85 respectively

Frayne D. R., “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Vol. 1: Presargonic Period (2700-2350 BC)”, (2008) Toronto

Lapinkivi P., “The Sumerian Sacred Marriage and Its Aftermath in Later Sources”, in:

Nissinen M. and Uro R. (editors), “Sacred Marriages: The Divine-Human Sexual Metaphor from Sumer to Early Christianity”, (2008) University Park, PA, at pp. 7-42

Magid G., “Sumerian Early Dynastic Royal Inscriptions”, in:

Chavalas M. W. (editor), “The Ancient Near East: Historical Sources in Translation”, (2006) Malden, MA and Oxford, at pp. 4-16

Marchesi G. (2006), "Statue Regali, Sovrani e Templi del Proto Dinastico: I Dati Epigrafici e Testuali”, in:

Marchetti N., "La Statuaria Regale nella Mesopotamia Proto Dinastica”, (2006) Rome, at pp. 205-71

Marchesi G., “Who Was Buried in the Royal Tombs of Ur?: The Epigraphic and Textual Data”, Orientalia, 73:2 (2004) 153-197

Margueron J.-C., "Mari and the Syro-Mesopotamian World", in:

Aruz J. and Wallenfels R. (editors), “Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium BC, from the Mediterranean to the Indus”, (2003) New York, at pp. 135-64

Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-292

Postgate J. N., “Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History”, (1994) Abingdon

Maeda T., “‘King of Kish’ in Presargonic Sumer”, Orient, 17 (1981 ) 1-17

Jacobsen T., “The Sumerian King List”, (1939) Chicago IL