Empires of Mesopotamia:

Kingdom of Kish

Empires of Mesopotamia:

Kingdom of Kish

Introduction

Map 1: Extent of the Akkadian and ‘Ur III[ Empires

Image adapted from Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2021, Map 2.1, at p. 69)

My additions: text in red and blue

As Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2021, at p. 44) observed, as far as we know:

“... the two earliest examples of imperial experiments on record [are]:

✴the empire of Sargon of Akkad (2300-2200 BC); and

✴the [empire of the so-called Ur III dynasty] (2100-2000 BC).”

However, Sargon’s ‘imperial experiment’ must have been conditioned by political developments in the surrounding region. Steinkeller (as above) pointed out that the Uruk had apparently played a leading role in a commercial and trading network that involved other city-states across much of the territory that later belonged to Sargon’s empire, albeit that the was:

“... emphatically not an empire, ... [albeit that it] was responsible for the establishment of the trading patterns and commercial routes existing later in the very same region.”

He then pointed out that:

“A more direct antecedent of the Sargonic Empire, in both time and space, was [probably] the kingdom of Kish

Archeological Evidence for Ancient Kish

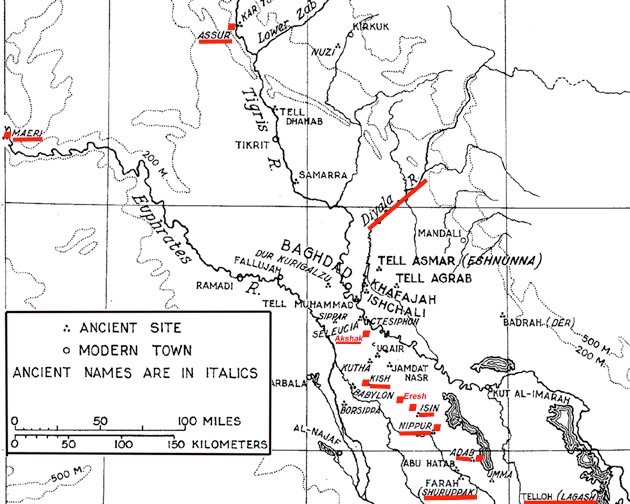

Map 2: Site of Ancient Kish

Image from Karen Wilson and Deborah Bekken (referenced below, Map 1, p. xviii): my additions in red

As Karen Wilson and Deborah Bekken (referenced below, at p. xix) pointed out, Kish was located on the floodplain of the Euphrates, some 12 km to the east of the later site of Babylon (80 km south of modern Baghdad). Excavations here have uncovered ancient remains under some 40 mounds that are scattered over an area of 2.4 km2. As Peter Moorey (referenced below, at p. xx) observed:

“Archaeologists and ancient historians now refer to [the totality of these mounds] as ‘Kish’, the ancient name of the city whose primary shrines lay about the standing ruin of an eroded ziggurat known locally as 'Tell Uhaimir. Until the ancient topography of the whole area is much better known from documentary sources, Kish suffices as a short-hand description for many closely related settlements extending back in time long before the use of writing, and running down to the Mongol invasion, long after the name of Kish had passed from record.”

Karen Wilson and Deborah Bekken (referenced below, at p. xix) asserted that the Euphrates originally divided the urban area of Kish into:

✴a western area, which was dominated by a ziggurat found at Tell Uhaimir (probably the site of the temple of Zababa, the city-god of Kish); and

✴an eastern complex at Tell Ingharra that the ancients knew as as Hursagkalama, which was the location of an important temple of Inanna.

However, Federico Zaina (referenced below, at p. 443), in a paper reporting on his recent review of the archeological evidence from Tell Ingharra (the most extensively explored area of ancient Kish) concluded that:

”... the hypothesis that views Tell Ingharra and Tell Uhaimir as independent villages [in the 3rd millennium BC] does not seem entirely convincing.”

Having said that, there is surviving epigraphic evidence that Kish was indeed divided in some way into two urban areas in the pre-Sargonic period: in two of the inscriptions in which Sargon commemorated his victory over Lugalzagesi of Uruk (RIME 2:1:1, inscriptions 1 and 2), we read that he also:

“... altered the two sites of Kish [and] made [them] occupy (one) city”, (RIME 2:1:1:2, CDLI P461927, lines 100-8).

Furthermore, Stephanie Dalley (referenced below, at p. 92) pointed out that, while Inanna/Ishtar eventually had temples in both locations, at least by the Old Babylonian period:

“Kish-Uhaimir and Hursagkalama-Ingharra were regarded as two separate cities as far as cults were concerned ... Zababa , [unlike Inanna/Ishtar], is never referred to as a god of Hursagkalama ... [and ancient] lists of temples also name the two cities separately.”

According to Francesco del Bravo (referenced below, at p. 303) archeological evidence (primarily from Tell Ingharra and Tell Uhaimir) indicates that:

“... between the Late Uruk and Early Dynastic IIIa-b periods, Kish underwent three stages [of urban development], each representing a significant expansion ... :

✴Late Uruk = 10.1 ha;

✴ED I = 137.2 ha;

✴ED III = 230.9 ha.

These data clearly show how, ... in the span of a few centuries, [Kish] not only [reached] an urban status but was [also] by far the largest occupied settlement in northern Babylonia, [at least as far as we know].”

During this period, the use of the Sumerian language in northern Mesopotamia increasingly gave way to a Semitic language dubbed ‘Akkadian’ (presumably reflecting a period of migration from the north). Aage Westenholz (referenced below, at pp. 690-1) observed that, although the textual evidence from Kish is not as extensive as one would like:

“There is sufficient textual material from ED IIIa ... to allow an assessment of the [Kishite] population around 2600 BC. The language of record of these texts is difficult to define ... [However], there are:

✴26 Sumerian names;

✴6 Akkadian; and

✴13 names of uncertain linguistic affiliation (though most of them may turn out to be Sumerian).

Bearers of Akkadian names thus made up 13.3% of the inhabitants of Kish [at this time], while well over a half were [still] Sumerians. ... During ED IIIb ..., the percentage of Akkadian names increases steadily, although the process is difficult to monitor, due to the scarcity of material.”

According to Federico Zaina (referenced below, at p. 444) the surviving archeological evidence suggests that the period of Kishite expansion:

“... ends abruptly at the end of the ED IIIb, with a violent destruction attested in several areas ... During the Akkadian period, Kish seems to be mostly occupied by graveyards and small squatter buildings. Its partial regeneration as a smaller centre [only begins] at the very end of the 3rd millennium BC, with the erection of a massive building ... close to the ziggurats of Ingharra.”

Early History of Kish

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2017, at p. 121) argued that the northern part of Mesopotamia (roughly, the Mesopotamian region north of Nippur, which included Kish):

“... formed a single territorial state, which was governed by the city of Kish, [albeit that] it appears that, on some occasions, its centre of power moved to Mari in the middle Euphrates valley and Akshak in the Diyala Region. The magnitude of the political power wielded by Kish (especially during the ED I and ED II periods) is reflected in the fact that the title of the ‘king of Kish’ eventually became a generic designation for the authoritarian and hegemonic form of kingship.”

This paragraph contains three hypotheses that are important for present analysis:

✴first, that, in the ED I and II periods, the rulers of the city of Kish also exercised an ‘authoritarian and hegemonic form of kingship’ over ‘a single territorial state’ in northern Mesopotamia; and

✴secondly, that this precocious example of hegemonic rule was remembered throughout Mesopotamia long after the political fortunes of Kish had declined; and

✴this was the reason why later rulers who exercised (or aspired to exercise) hegemony in Mesopotamia adopted the title LUGAL KISH in order to underscore their own political legitimacy.

Kishite Hegemony in Northern Mesopotamia (3rd Millennium BC) ?

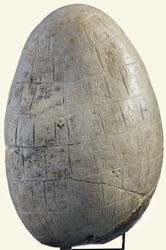

Evidence of the ‘Prisoner Plaque’

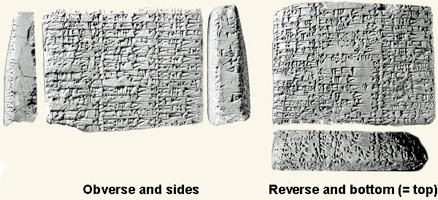

So-called ‘Prisoner Plaque; image from CDLI, P453401

In support of the first of these hypotheses, Piotr Steinkeller referred back to one of his earlier papers (referenced below, 2013) on the alabaster plaque illustrated above, which he characterised (at pp. 144-5) as:

“... the earliest truly historical source that survives from ancient Mesopotamia.”

The provenience of the plaque is unknown: it was apparently in a private collection when Steinkeller published his paper, although he was able to examine high quality photographs and to access information about its material and measurements. He argued (at p. 132) that:

“On the basis of its script, the plaque may tentatively be dated to the ED II period or (although less likely) to the ED I period.”

More recently, Camille Lecompte (referenced below, at pp. 440-3) dated it to the later part of the ED II period. The shallow relief on the front, which depicts two standing male figures facing left, carrying bows and other objects, is relatively uninformative. However, the main body of the six-column text, which is written in Sumerian cuneiform, is made up of a list of captives from at least 25 different locations (listed at p. 133) and the number of captives from each. Steinkeller offered the following tentative translation of these final lines of the surviving text (at p. 133):

“36,000 captives

(They were assigned) to the filling of threshing floors (with grain) and the making of grain stacks

The stone (monument) fashioned in Kish

Zababa is the god of manhood”, (col. vi, lines 3’-7’).

It ends on the lower right edge with the name of the scribe, Amar-SHID. Since the surviving text records 28,970 captives (see p. 133), and assuming that the figure 36,000 represents the original total, it seems that about 20% of the original text has been lost.

Steinkeller argued (at p. 132) that:

“The plaque almost certainly stems from Kish (or one of its [putative] dependencies, [as] is assured by the following data:

✴the plaque mentions Zababa, the patron god of Kish (vi 7');

✴the city of Kiš is likely named in it as well (vi 6');

✴the signs, sign-values and other paleographic features of the inscription show strong connections the early written materials from Kish and from northern Babylonia more generally ... ;

✴the [25] toponyms named in the [surviving part of the] inscription include [at least 8] that also appear in the Early Dynastic ‘List of Geographical Names’ ... [see the discussion below]; and

✴the scene depicted on the [obverse] shows similarities to an ED II inlaid frieze excavated at Kish [see his Figure 5, at p. 153].

He argued (at p. 142) that:

“As best as it can be ascertained, the plaque is a record of the prisoners of war who were acquired as booty by the state of Kish in the course of its territorial conquests. The preserved sections of the the plaque name 25 conquered places, with one of them (Asha) appearing twice (i 10', ii 7'). The numbers of prisoners per toponym vary from to 50 (i 15') to 6,300 (v 5'). Given the wide variation among the numbers, there is every reason to think that these are real, and not inflated, figures. Since the numbers, as preserved add up to 28,970 captives, with a significant number of entries presently missing, it is likely that the figure of the total (36,000) likewise is a real one, though probably slightly rounded up”; and

suggested (see p. 143) that:

“Both the large number of localities conquered and the huge figures of captives so obtained speak against the possibility that the plaque describes the outcome of a single military campaign. Much more likely, in my view, [is the hypothesis that] we find here a cumulative record of the conquests carried out by Kish over a period of time.

He concluded (at p. 145) that the ‘Prisoner Plaque’:

“... provides priceless about the formation and the territorial conquests of the state of Kish during the phases of the ED period. In this connection, particularly eloquent is the mention of 6,300 captives acquired in the land of Shubur (Assyria). Here, one witnesses not only the oldest occurrence of Assyria's name, but also a palpable proof of Kish’s foreign expansion. The plaque also confirms what had been suspected by some scholars (this one among them) about the early Kishite state, [particularly in relation to its putative] hegemonic and militaristic character. The figure of 36,000 prisoners of war ... recorded in the plaque is astonishing, since it was not until the advent of Sargon of Akkad and his [successors] that rulers again were able to aspire to similar military feats. Because of this, the state of Kish considered [by these scholars to be] a forerunner of the Sargonic empire.”

Steinkeller acknowledged (at p. 144) that:

“... the plaque does not name the ruler (or rulers) responsible for these conquests and the bringing of the captives to Kish (though it is possible that his name appeared at the very beginning of the inscription, now missing). Instead, its concluding lines praise Zababa, the divine master of Kish and (fittingly) a god of war."

It seems to me that, if this ‘document’ originated in Kish (as was probably the case), then it is very likely that (for reasons discussed below) this ruler was named as the king of Kish, who (in local tradition) had been given this hallowed, god-given kingship by (or at least with the help of) Zababa.

Note, however, that nothing in the surviving text on the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ indicates the circumstances in which any or all of the 36,000 captives were taken. Steinkeller assumes that they had been captured during successive campaigns of conquest that had culminated in the hegemony of Kish over a huge part of northern Mesopotamia that extended at least as far north as Assyria, on the upper reaches of the Tigris. However, it is equally possible that some or all of these captives were taken in raids that were aimed primarily at the acquisition of slaves rather than territory. Furthermore, as Aage Westenholz (referenced below, at p. 697) pointed out, even if some or all of them had been taken in battle from localities that had defeated, the surviving text:

“... scarcely proves the existence of a territorial state in the north, [centred on Kish], any more than [the evidence for] Eanatum’s campaigns ... [against enemies from distant cities in the ED IIIb period - see below] prove the existence of a territorial state in the south, centred on Lagash.”

In other words, while the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ arguably confirms the ‘militaristic character’ of Kish in the ED II period, it does not offer any evidence that the Kishites either claimed or achieved hegemony over dozens of cities, including some as far away as Assyria to the north and/or the Diyala valley to the northeast.

Evidence of the Early Dynastic ‘List of Geographical Names’ (LGN)

Map 3: and the LGN

Image from Karen Wilson and Deborah Bekken (referenced below, Map 1, p. xviii): my additions in red

Walther Sallaberger and Ingo Schrakamp (referenced below, at p. 65) observed , the list of localities known from a number of fragments from Abu Salabikh [= Eresh] that:

“... can be reconstructed on the basis of a completely preserved duplicate from Ebla [in modern Syria] and other recently published duplicates of unknown provenance. Only a tiny fraction of the 289 toponyms [in the list] can be identified and related to places attested in administrative texts from other archives. [According to Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 1992) they] belong to two groups;

✴[the toponyms of the first group were] located in the north of Babylonia; and

✴[those] in second group [were located] in the Transtigridian region (between the Tigris and the Zagros mountains to the east), the Zagros and Khuzistan.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, p. 148) argued that:

“Since the LGN was known already in the ED IIIa period, [the likely date of the Abu Salabikh text], it must reflect a considerably earlier situation.”

He also argued (at p. 147) that:

“... Kishite scribes were apparently the first to use cuneiform to record historical inscriptions (as demonstrated by the ‘Prisoner Plaque’) ... They also compiled new lexical texts, ... [including the LGN].”

In other words, he argued that:

✴the list of captives in the ‘Prisoner Plaque’; and

✴the list of localities in the LGN;

were both compiled at Kish in the ED II period.

Locations mentioned in both the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ and the ED ‘List of Geographical Names’

See Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 142)

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, p. 148) further argued that, although the putative Kishite ‘territorial state’:

“... probably came into being during the ED I period, its greatest territorial expansion and political power belonged to ED II. While the [‘Prisoner Plaque’] offers the strongest and most persuasive evidence here, there are other important indications as well, ... [one of which is] the testimony of the LGN] ...”

This body of evidence from the LGN (which Steinkeller established at p. 142) is summarised in the table above: in short:

✴8 of the 25 localities mentioned in the surviving text of the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ can (or can probably) also be found among the 289 localities in the LGN; and

✴3 of these 8 localities can (or can probably) be identified at known ‘modern’ locations.

Importantly, the list of captives in ‘Prisoner Plaque’ included:

✴6,300 from Shubur/Assyria (LGN 233), on the upper reaches of the Tigris; and

✴1,340 from the Uri, the region of the Diyala river.

Steinkeller argued (at p. 132, citing one of his earlier papers) that the LGN:

“... represents a gazetteer of the archaic territorial state of Kish.”

Furthermore, on the basis of this hypothesis, he argued (at p. 148) that, by the time that the now-unknown king of Kish commissioned the ‘Prisoner Plaque’he exercised hegemony over:

“... the entire territory of northern Babylonia, most northern section of southern Babylonia (Nippur, Isin and Eresh) and large portions of of the Diyala Region. The Kishite expansion also affected Assyria [on the upper reaches of the Tigris ...”

I assume that the point here is that:

✴Nippur (LGN 177) and Isin (LGN 70), along with Sharrakum (LGN 167, which was probably close to Adab) seem to have marked the southern boundary of the territory covered by the LGN;

✴Eresh (Abu Salabikh), which was only 20 km northwest of Nippur, was the find spot of surviving fragments of the LGN; and

✴two location at the periphery of the territory covered by the LGN:

•Uri (the Diyala region), which lay to the east; and

• Shubur (Assyria), which to the north:

were actually named in the ‘Prisoner Plaque’.

Aage Westenholz (referenced below, 2020, at pp. 697-8) pointed out that the logic underlying Steinkeller’s conclusion:

“... [that] ‘the state of Kish embraced the entire territory [covered by the LGN] is really a bit of circular reasoning:

✴because the LGN enumerates cities in those regions, it is assumed to be a gazetteer of the Kishite state; and

✴on the strength of that assumption, it proves the extent of that state!”

He also pointed out (at pp. 691-2) that:

✴only six relevant administrative documents from Kish (which all date to the ED IIIa period) survive and, of these:

•one (Ashmolean 1928-435, P222333) names Asha (LGN 41), which (as we have seen) also appears twice in the Prisoner Plaque (as the source of 1500+489 captives); but

•none of the other 5 names a single locality that appears in either of the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ or the LGN; and

✴the only fragment of a lexical list of geographical names from Kish itself (Ashmolean 1931-145, P451600), which dates to the of ED IIIa period:

“... appears to belong to a series hitherto unknown.”

He conceded concluded (at p. 692) that:

“... there is only slight support from Kish for the idea that the LGN is a gazetteer of the Kishite kingdom. In fact, the very idea that [the LGN] is a ‘gazetteer’ of anything is problematic: where do we find parallels to that? Furthermore, a good number of the place names in the LGN are also mentioned in the administrative documents from Fara.”

In other words, the evidence from the LGN does not provide significant support for the hypothesis that an ‘archaic territorial state of Kish ... embraced of northern Babylonia, the most northern section of southern Babylonia (Nippur, Isin, and Eresh), and large portions of the Diyala Region’.

Kishite Hegemony in Northern Mesopotamia (3rd Millennium BC): Conclusions

It seems to me that, while the ‘Prisoner Plaque’:

✴almost certainly originated in Kish in the ED II period, at a time when immigrants who used a Semitic language were arguably beginning to influence the ‘native’ Sumerian culture; and

✴indicates that Kish was a militarily aggressive polity whose ruler (almost certainly by a king - see below) had what seems to have been a precocious understanding of the part that ‘royal’ inscriptions could play in advertising military success and associating it with god-given ‘legitimate kingship’;

it does not, in itself. indicate that the listed captives came from localities that. formed part of a Kishite ‘territorial state’. Indeed, Piotr Steinkeller did not claim that it did: he argued (1t p. 148) that, while, in his view, the ‘Prisoner Plaque’:

“... offers the strongest and most persuasive evidence [for this hypothesis], there are other important indications as well.”

One of these was the LGN but, it seems to me that, while this ‘document’ can be said to belong to the same linguistic culture as the ‘Prisoner Plaque’, it does not allow us to hypothesise that the captives listed in the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ came from territory that formed part of a Kishite ‘territorial state’. However, Steinkeller’s other supporting evidence must also be considered. I discuss this important body of evidence in the following two sections:

✴the first dealing with the individual kings of Kish in the pre-Sargonic period; and

✴the second dealing with the perception of the title ‘King of Kish in Mesopotamia thereafter.

Kings of Kish in the Pre-Sargonic Period

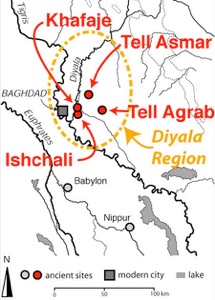

Map of Mesopotamia during the 3rd millennium BC

From the website of the Lagash Archeological Project: my additions in red

As Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, at p. 5) observed, one of the things:

“... complicating the historical picture in ED times is the fact that the title ‘lugal kish’ of ED royal inscriptions, while clearly referring in some cases to actual kings of Kish (such as Enmebaragesi), seems, at other times, to be an honorific epithet meaning something like ‘king of the world’.”

He therefore assigned two of the kings of Kish discussed below (Mesalim and Enna-il) to his Chapter 8: ‘Rulers with the Title ‘King of Kish’ whose Dynastic Affiliations are Unknown’. However, in what follows, I have followed other scholars (for example, Gianni Marchesi and Piotr Steinkeller) who regard all of Enmebaragesi, Mesalim and Enna-il as ‘actual kings of Kish’.

Enmebaragesi, King of Kish, and his Son and Successor, Akka

Map of the Diyala Basin: image from the website pf the ‘Diyala Project’’ (University of Chicago)

As Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, at p. 55) observed:

“The first king of Kish for whom we have any inscriptions is Enmebaragesi”.

More specifically, he is probably:

✴the ‘Mebaragesi’ whose name appears on a fragment of a stone bowl from Khafayah (ancient Tutub) in the Diyala valley (RIME 1:7: 22:1; CDLI. P431026), although only this single word survives and/or

✴the ‘Mebaragesi, king of Kish’, whose name appears on a similar fragment of unknown provenience (RIME 1:7:22:2; CDLI, P431027).

Furthermore, as Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p.149 and note 71) observed, a third broadly contemporary inscription (RIME 1:7:40:1; CDLI, P431028) on a fragment of a stone vessel from Tell Agrab, which records the name of a now unknown king of Kish (son of Munus-ul4-gal) confirms the Kishites’ connections with the Diyala region at this time.

There is no reason to doubt that Enmebaragesi was an actual ruler of the city of Kish: as we shall see:

✴he is named (as Enmebaragesi, the father and predecessor of Akka) in:

•the surviving part of the USKL (and he is the only one of the 19 Kishite kings listed here who is also known from his royal inscriptions); and

•in the later SKL (in which he is additionally described as having destroyed Elam); and

✴he is also known (as Enmebaragesi, father of Akka) in the literary traditions of Ur and Uruk, in which both Enmebaragesi and Akka exercised hegemony over Uruk until the city was liberated by the (probably mythical) Urukean hero Gilgamesh.

Nicholas Postgate (referenced below, 1994, at pp. 29-30) argued that both of the inscriptions of Enmebaragesi discussed above probably came from a temple at Khafayah, and that the parallels between these dedications and those made subsequently by Mesalim, king of Kish, at temples in Girsu and Adab (see below) suggest that Khafayah acknowledged the hegemony of Enmebaragesi. However, there is specific evidence that Mesalim exercised hegemony at Girsu and Adab, which is not the case for Enmebaragesi in the Diyala. Having said that, as Steinkeller noted (at p. 148 and note 69), a biographical note in the Old Babylonian SKL ascribes the conquest of Elam to Enmebaragesi, and (if this is accurate), he would have marched on Elam via the Diyala valley. In other words, we cannot discount the possibility that the 1,340 captives from ‘Uri’ recorded in the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ had been associated with Kishite territorial expansion here in this period.

Mesalim, King of Kish: Lagash, Umma and Adab

Mace-head of Mesalim, King of Kish (RIME 1.8.1.1; P462181), from Girsu

Now in the Musée du Louvre (AO 2349), images from the museum website

Mesalim is a key figure for our understanding (such as it is) of the political situation in Sumer in the ED Period. Three of his royal inscriptions survive:

✴One from Girsu, which was found on a stone mace-head (illustrated above), recorded that:

“Mesalim, king of Kish, temple builder for the god Ningirsu, set (?) this mace for the god Ningirsu [when] Lugal-sha-engur (was) ensi of Lagash”, (RIME 1.8.1.1; P462181).

The top of the mace-head is carved with a relief of a lion-headed eagle known as Imdugud (= Anzu), who was closely associated with Ningirsu, the city god of Lagash, while the inscribed curved surface has a frieze relief of six lions biting each other, which is another example of local iconography.

✴The other two inscriptions come from the Esar temple at Adab:

•one, which was found on fragments of two stone bowls, recorded that:

“Mesalim, king of Kish, sent over this bur mu-gi4 (stone bowl, used for the burgi ritual) in the E-SAR [when] Nin-KISAL-si (was) ensi of Adab”, (RIME 1.8.1.2; P462182); and

•the other, which was found on a fragment of a chlorite vase, recorded that:

“Mesalim, king of Kish, beloved son of Ninhursag [the city goddess of Adab, dedicated this vase ??] ...”, (RIME 1.8.1.3; P431033).

Importantly, as Nicholas Postgate (referenced below, 1994, at p. 30) observed, it is clear from these inscriptions that both:

✴Lugalshaengur, ensi of Lagash; and

✴Ninkisalsi, ensi of Adab;

acknowledged the hegemony of Mesalim, king of Kish.

Unusually, we know more about Mesalim from the royal inscriptions of later rulers (in this case, rulers of Lagash). For example, about a century after Mesalim’s rule, Eanatum, ensi of Lagash, looked back on his as the original arbitrator of a boundary dispute between Lagash and Umma in:

✴an inscription (RIME 1.9.3.2; P431076) found on three boundary stones; and

✴a very similar inscription (RIME 1.9.3.3; P431077) found on two spheroid jars;

all of which came (or probably came) from either Girsu or Lagash. More specifically, Eanatum recorded that, after his victory in a boundary dispute Umma, he had:

✴restored the boundary stele that Mesalim had erected to mark the boundary between the respective territories, which had originally been defined by the god Enlil (see, for example, RIME 1.9.3.2; P431076, lines 4-7); and

✴stressed that, in deference to the gods, he had not marched beyond the point (see, for example, RIME 1.9.3.2; P431076, lines 55’-60’).

Fortunately, we have a more complete account of these events from a royal inscription of a yet-later ensi of Lagash, Enmetena (Eanatum’s nephew): at the start of his account of his own boundary dispute with Umma, he looked back on the precedents set by Mesalim and Eanatum:

“Enlil, lugal kur-kur-a (king of all lands), ab-ba dingir-dingir-re2-ne-ke4 (father/elder of all the gods) ... demarcated the border between:

✴Ningirsu, [the city god of Lagash and Girsu]; and

✴Shara, [the city god of Umma].

Mesalim, king of Kish, at the command of Ishtaran, [originally] demarcated this border and erected a monument there. Ush, ensi of Umma, acted arrogantly: he smashed that monument and marched on the plain of Lagash. Ningirsu, warrior of Enlil, at his (Enlil's) just command, did battle with Umma. ... Eanatum, ensi of Lagash, demarcated the border with Enakale, the ensi of Umma. ... He inscribed (and erected) monuments at [the god-given border] and restored the monument of Mesalim, but did not cross [the border] into the plain of Umma”, (RIME 1.9.5.1; P431117, lines 1-58).

As Aage Westenholz (referenced below, 2020, at p. 696) observed, in this later inscription:

“Mesilim is said to have acted in accordance with the [command of] ... Ishtaran, [who] was the divine protector of treaties, as indicated by the spelling of his name dKA.DI (god of just verdict).”

It is clear from these later testimonies that Mesalim’s authority as hegemon in the resolution of boundary disputes between Lagash and Umma was long-remembered, at least at Lagash.

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 148 and note 64) suggested that:

“... Mesalim (whose reign [arguably] dated to the ED II [period] exercised hegemony over the southern city-states of Adab, Umma and Lagash and, by the implication, over all of southern Babylonia north of Uruk. ... This phase of the interactions between the Kishite kingdom and southern Babylonia may find reflection in the heroic poem ‘Gilgameš and Akka’. Although written down in Ur III times, this poem likely goes back to a much earlier oral composition.”

In fact, there is no real evidence that this Kishite hegemony extended further south than Adab, Umma and Lagash in the ED II period.

Enna-il, King of Kish

Gianni Marchesi( referenced below, 2015, at pp. 152-4) produced a list of 12 documented ‘kings of Kish’ in the pre-Sargonic era in roughly chronological order, three of which (Enmebaragesi, Akka and Mesalim) were discussed above. He also listed Enna-il (at number 9, p. 143), who is known from two royal inscriptions from Nippur:

✴one (RIME 1.8.3.1, P462184), which seems to be an Ur III period copy of the original, recorded that Enna-il, son of A-anzu, had defeated Elam ‘for the goddess Inanna’; and

✴the other (RIME 1.8.3.2, P462185), which is written in Akkadia, recorded that Enna-il, king of Kish, had set up a statue of himself ‘before Ishtar (= Inanna)’ (see lines 14’-20’).

(For some reason, the CDLI places these inscriptions in Adab, but this seems to be a mistake). It therefore seems likely that Enna-il set up his statue at the temple of Inanna at Nippur. Furthermore, Marchesi suggested (at note 19, p. 140) that, given this find spot of these inscriptions, we might reasonable assume that:

“Nippur was still in the orbit of Kish at the time of Enna-il ...”

Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, at p. 148) also observed that the inscription RIME 1.8.3.1 (above) provides further proof of the Kishites’ eastwards expansion into Elam (although there is no suggestion of Kishite hegemony over any Elamite territory).

Gianni Marchesi (referenced below, 2011, at p. 180 and note 108) referred to an unpublished inscription on a statue of the god Shara, which can be freely translated as follows:

“Uriri, the chief cook, presented (this statue) to Shara [when] Hinna’il [= Enna-il] was king of Kish.”

Since Shara was the city god of Umma:

✴Marchesi (as above) suggested that Enna-il was probably an ‘overlord’ and that this statue possibly came from Umma; and

✴Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013, note 67, at p. 148) argued that the inscription on it:

“... probably [indicates that] Enna-il exercised some form of suzerainty [hegemony ??] over Umma.”

In the chronological tables that Marchesi published subsequently (Gianni Marchesi, referenced below, 2015), he suggested that:

✴in the period after the reign of Mesalim (above), both Adab and Umma regained their independence (Tables 1.1, at p. 141);:

✴no ruler of Umma is known during the subsequent reign of Enna-il, but Umma regained its independence shortly thereafter (Tables 1.2, at p. 142).

He therefore argued (at note 19, p. 140) that Enna-il:

“...was probably the last great king of Kish proper, [in the sense that his capital was at Kish].”

Meskalamdu and Mes-Ane-pada: Kings of Ur and of Kish

Lapis lazuli bead (RIME 1.13.5.1, P431203) from Mari

Now in the National Museum, Damascus: image from Jean-Claude Margueron (referenced below, at p. 143)

The inscription (P247679) on a seal from the royal cemetery of Ur that is now in the British Museum (exhibit BM 122536) reads: ‘mes-kalam-du10 lugal’, (Meskalamdu, the king). Given the find spot, we might reasonably assume that Meskalamdu was the king of Ur. However the inscription (RIME 1.13.5.1, P431203) on an eight-sided bead (illustrated above), which was excavated from the site of the royal palace at Mari reads:

“For [...]: Mes-Ane-pada, king of Ur, the son of Meskalamdu, king of Kish, has consecrated (this bead)”, (translation from Jean-Claude Margueron (referenced below, at p. 143).

Thus, Meskalamdu seems to provide us with an example of an ED ruler in Sumer who used the title ‘king of Kish’, despite the fact that his capital was located at somewhere other than Kish (i.e., in this case, at Ur).

Turning now to Mes-Ane-pada himself, who is named as the king of Ur on this bead, which was found in a jar with other precious objects in the ‘sacred precinct’ of the Pre-sargonic place at Mari. The excavators characterised these objects as the ‘treasure of Ur’ and speculated that this ‘treasure’ had been a royal gift from Ur. However, it has subsequently emerged that the objects themselves are quite disparate, and the circumstances in which this particular object its way to Mari are actually unknown. Furthermore, there is some doubt about the identity of the god to whom Mes-Ana-pada dedicated it : for example:

✴Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, RIME 1.13.5.1, at p. 392) gave ‘an lugal-[ni]’ (to the god An, his lord); while

✴Glenn Magid (referenced below, at p. 10) and the entry at CDLI, P431203 give ‘{d}lugal-kalam’ (to the god Lugalkalam).

Thus, the only thing that we can take from the inscription is that Mes-Ane-pada used the title ‘king of Ur’ at a time when his father, Meskalamdu, (who was presumably still alive) used the title ‘king of Kish’.

Seal of Mes-Ane-Pada (RIME 1,13.5.2, P431204) from Ur

Now in the Penn Museum (Sealing 31-16-677), image from museum website

Interestingly, we know from another inscription (RIME 1.13.5.2, P431204), which is on a clay sealing from Ur (illustrated above), that Mes-Ane-pada himself used the title ‘king of Kish’, presumably after his father had died. There is no surviving evidence that either Meskalamdu or Mes-Ane-pada ever held both titles at the same time. It is possible (but by no means certain) that Kish was actually subject to the hegemony of Ur in the reigns of these kings but, even if it was, this would not explain why Mes-Ane-pada used the title ‘king of Kish’ on what was probably his ‘official’ seal at Ur. Interestingly, A-Ane-pada, the son and successor of Mes-Ane-pada, is always and only entitled ‘king of Ur’ in his surviving inscriptions (see Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 2008, at pp. 395-8).

Mes-Ane-pada used a second title of his official seal: dam nu-gig (spouse of the nugig). Glenn Magid (referenced below, at p. 6) observed that nugig could have been either:

✴the name of one of Mes-Ane-pada’s actual wives; or

✴the name of:

“... a well-known type of priestess. If so, then [this inscription] would constitute the earliest evidence for a ritual that is otherwise attested only later in Mesopotamian history: the annual ‘sacred marriage’ between the king and a goddess (embodied in the person of her priestess).”

Petr Charvát, referenced below, 2017, at p. 196 and note 37) translated nugig as ‘the Lofty One’, and observed that this could have been either a reference to the ‘nugig priestess’ (a priestess of Inanna) or an epithet Inanna herself. Pirjo Lapinkivi (referenced below, at pp. 18-20) observed that:

“Enmerkar, the legendary king of Uruk, was the earliest Sumerian ruler who called himself Inanna’s husband. ... Even if the evidence [of the Enmerkar legend] is questionable, there are other sources that indicate an affectionate relationship between the Sumerian ruler and the goddess of love as early as the ED II period: [for example], there is a seal impression of Mes-Ane-pada ... [that] declares [him] to be ‘the husband of the nu-gig’. The term nu-gig probably refers to the common epithet of Inanna ... The impression also has designs of a star and a crescent moon, which were both common symbols for Inanna in her astral aspect (the planet Venus and the morning and evening star).”

As we shall see, this is the earliest of a series of indications that the title ‘king of Kish’ might have been in the gift of the goddess Inanna (a suggestion first made by Tohru Maeda (referenced below, 1981, at pp. 7-9).

Eanatum, Ensi of Lagash and King of Kish

Eanatum Boulder, from Girsu (now in the Musée du Louvre: AO 2677)

Image from the museum website

As discussed above, Aage Westenholz (referenced below, at p. 697) argued that, even if the prisoners listed on the ‘Prisoner Plaque’ at Kish (many of whom came from distant localities) could be shown to have been taken in battle, this would :

“... scarcely [prove] the existence of a territorial state in the north, [centred on Kish, as hypothesised by Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below, 2013)], any more than [the evidence for] Eanatum’s campaigns ... [against enemies from distant cities] prove the existence of a territorial state in the south, centred on Lagash.”

This is a reference to a campaign recorded of the so-called ‘Eanatum Boulder’ (illustrated above), in which we read that:

“Because Inanna so loved Eanatum, the ensi (ruler) of Lagash, she gave him nam-luga[ (the kingship) of Kish, together with nam-ensi2 (the rulership) of Lagash:

✴Elam trembled before him (and) he sent the Elamite back to his land.

✴Kish trembled before him.

✴He sent [Zuzu], the king of Akshak, back to his land.

Eanatum, the ruler of Lagash, who subjugates foreign lands for [the god] Ningirsu, defeated:

✴Elam, Subartu [= Shubur, Assur, Assyria ] and Uru at the Asuhur [canal (?) ... ; and]

✴Kish, Akshak and Mari at the Antasura of Ningirsu”, (RIME 1.9.3.5, P431079, lines 98-126).

(See Map 3 above for Assur/ Subartu, Akshak and Mari.). Steinkeller had argued (at p. 150) that, since Eanatum’s battle(s) were explicitly fought near Lagash, they had been largely defensive, but Westenholz countered (at p. 688) that:

“... Eanatum surely did more than merely seeing his enemies off:

✴Zuzu of Akshak was pursued all the way to the safety of his own city, soundly beaten.

✴Eanatum ... claimed to be ‘king of Kish’, and a fragment of an inscription of his has actually been excavated there, as if to prove the veracity of that claim.

Even so, his dominion over the north was probably quite short-lived.”

(The inscription to which Westenholz referred is in the Ashmolean Museum (Ashm, 1930-204; P221781): Westenholz read ‘[é-an-na-túm / …] / [dumu] a-ku[r-gal’ in the broken passage, and identified this as Eanatum, son of Akurgal, ensi of Lagash).

USKL Recension

Surviving part of the tablet containing the Ur III recension of the Sumerian King List (USKL):

the tablet is in a private collection and the image adapted from CDLI: P283804

In 2003, Piotr Steinkeller (referenced below) published what was (and is still) the earliest known version of the SKL, which is on a clay tablet that was (and is still is) in a private collection: he provided a transliteration of and an important initial commentary on the text, and a transliteration and photographs are also available on line at CDLI: P283804. In what follows, references to specific lines in these texts adopt the numbering system used by the CDLI.

Since the final lines of the text are complete, we know that the scribe dedicated his handiwork to:

“... [the divine] Shulgi, my king: may he live until distant days (see, for example, the translation by Piotr Steinkeller, referenced below, 2003, at p. 269).

As he pointed out:

“... by all indications, Shulgi was still alive when [this text] was written down, as the invocation suggests.”

He also argued (at p. 269) that, since Shulgi was given a divine determinative in this dedication, it must have been compiled at some time between:

✴his 20th regnal year (the approximate date of his deification); and

✴his 48th regnal year (the approximate date of his death).

We can thus date this recension of the SKL to the reign of Shulgi, the son and successor of Ur-Namma, who was the founder of what we know as the Ur III dynasty and the last-named king in this recension (hereafter the USKL).

First King of Kish in the USKL and the SKL

As we have seen, the USKL began with the record of Gushur, who was king of Kish at the time that the kingship itself first descended from heaven. As it happens Andrew George (referenced below, 2020, at p. 80) recently established that Gushur also appears (named as Gushur-nishī) in the prologue of an Akkadian poem about the the longstanding rivalry between a tamarisk tree and a date palm that survives in both an Old Babylonian (ca. 1750 BC) and a Middle Assyrian (ca. 1250 BC) recension:

✴the Old Babylonian prologue (which George translated at p. 79) includes for following lines:

“To bring justice to the people <like> a judge, [the gods] named Gushur-nishi as king to govern the [people] of Kish, the black-headed race, the numerous folk. The [king] planted a date-palm in his courtyard, [and surrounded it with] tamarisk ...”; while

✴in the Middle Assyrian prologue (which George translated at p. 82), the story was elaborated as follows:

“The gods of the lands held a meeting [in which] Anu, Enlil and Ea took counsel together. Among them was seated Shamaah [and] between was seated the great Lady of the Gods. Formerly there was no kingship in the lands, and power to rule was bestowed on the gods. [However], the gods so loved Gushur-nishi [that] they decreed for him the black-headed folk. The king planted a date-palm in his palace [and surrounded it with] tamarisk.”

As Andrew George pointed out (at p. 87), this confirms that:

“In one Babylonian understanding of history, [which was adopted in the USKL and the earliest recensions of the SKL], kingship ... was bestowed first on Kish, [and] Gushur was the first king of all.”

However, an alternative ‘Babylonian understanding of history’ is adopted in the prologues of the Akkadian text known as the ‘Epic of Etana’, which survives in fragments from the Old Babylonian and the Standard Babylonian (ca. 1100 BC) periods.

✴the Old Babylonian fragment in the Morgan Library Collection records that:

“The great Anunna-gods, ordainers of destiny, sat taking counsel with respect to the land. Those creators of the world regions, establishers of all physical form, those sublime for the people, the Igigi-gods, ordained the holy day for the people. Among all the teeming peoples, [the gods] had established no king: neither headdress nor crown had been put together, nor yet had any sceptre been set with lapis. No throne daises had been constructed. Full seven gates were bolted against the hero. Sceptre, crown, headdress, and staff were set before Anu in heaven. ... (Then) did [kin]gship come down from heaven” (lines 1-14); and

✴the Standard Babylonian I text records that:

“[The gods] planned the city [Kish]. The Anunna-gods] laid its foundations. The Igigi-gods founded its brickwork [...]. Let [a ma]n be their (the people’s) shepherd, ... Let Etana be their master builder ... The great Anunna-gods, or[dainers of destinies], [sa]t holding their counsel [concerning the land]. Those who formed the four regions of the world, the right and [left] (banks of the rivers), By command of all of them, the Igigi-gods [ordained the holy day for] the peop[le]. No [king] had they [yet] established [over the teeming peoples]. At that time, [no headdress had been put together, nor crown], Nor yet [had any] sceptre [been set] with lapis. No [throne daises] whatsoever had been constructed. The seven gods barred the [gates] against the multitude. ...The Igigi-gods surrounded the city [with ramparts]. Ishtar [came down from heaven to seek] a shepherd: she sought for a king [everywhere]. Enlil examined the lofty dais [in the city ...] She [Ishtar ?] has constantly sought ... [Let] king[ship be established] in the land, let the heart of Kish [be joyful]”, (lines 1-25).

As Evelyne Koubková (referenced below, at p. 375) pointed out, it seems that Etana did not actually receive the kingship of Kish in either prologue before the story moved on to describe (at considerable length) the circumstances in which Etana found himself making three attempts to ascend to heaven on the back of an eagle. The only surviving record of Etana’s successful arrival in heaven is in the Standard Babylonian III text, which preserves two relevant fragments:

✴in the first fragment, after two unsuccessful attempts, Etana explains to the eagle that he has had a dream in which:

“We passed through the gates of Anu, Enlil, [and] Ea [and did obeisance [together] ...

We passed through the gates of Sin, Shamash, Adad and Ishtar [and did obeisance together ...

I saw a house, I opened [its] seal, I pushed the door open and went inside.

A remarkable [young woman] was seated therein, wearing a tiara, beautiful of [fe]ature,

Under the throne lions were [c]rou[ching], [and], as I went in, the lions [sprang at me].

I awoke with a start and shuddered [...]”, (lines 3’-14’); and

✴in the second fragment:

“After [Etana and the eagle] had ascended to the heaven of A[nu], [they] passed through the gates of Anu, Enlil, and Ea [and]did obei[sance to]gether.

[They then passed] through the gates of Sin, [Shamash, Adad, and Ishtar and did obeisance together].

[Etana] saw [a house, he opened its seal], he pushed [the door open] and [he went inside] ... (lines 39’-45’).

Thus as Evelyne Koubková (referenced below, at p. 376) concluded:

“At the end of the preserved text, Etana gets to the highest heaven where he meets a goddess seated on a throne with lions at her feet, undoubtedly to be identified with Ishtar [whom he had already seen in his dream]. From this, I would infer that only at the end does the hero obtain his royal insignia: until that moment, these were lying in heaven in front of the god Anu ..., and it is precisely to this place that Etana goes. Therefore, one level of the myth presents Etana’s transition into a new mode of existence, namely to the state of being king.”

Comparing the epically transmitted material with that of the Sumerian King List, two things stand out. First, the Sumerian King List does not identify Etana as the first ruler in Kish, but names him after at least nine earlier kings (Gabriel 2020, 363 f.).

Second, it is striking that the Sumerian King List mentions a line of succession before Etana. According to this source, dynastic rule seems to have begun before Etana. That kings are mentioned before him is not initially a problem, since the Sumerian King List combines and condenses various sources.27 However, with regard to the concept of rule, the existence of a line of succession among the earlier kings is problematic (cf. also Diakonoff 1959, 167). This would mean that the Sumerian King List deviates at this point from the Etana material of the epic tradition. There, the beginning of the dynastic rule is linked to Etana's ascension to heaven (see 3.1).

Postgate J. N., “City of Culture 2600 BC: Early Mesopotamian History and Archaeology at Abu Salabikh”, (2024) Oxford

Artemov N., “LUGAL KIŠ and Related Matters: How Ideological are Royal Titles?”, in

Portuese L. and Pallavidini M. (editors), “Ancient Near Eastern Weltanschauungen in Contact and in Contrast: Rethinking Ideology and Propaganda in the Ancient Near East”, (2022) Münster, at pp. 67-85

Schneider B., “Nippur: City of Enlil and Ninurta”, in

Galoppin T. et al. (editors), “Naming and Mapping the Gods in the Ancient Mediterranean: Spaces, Mobilities, Imaginaries (Volume 1)”, (2022) Berlin and Boston, at pp. 745-62

Gabriel, G. I.,"Von Adlerflügen und Numinosen Insignien: Eine Analyse von Mythen zum Himmlischen Ursprung Politischer Herrschaft nach Sumerischen und Akkadischen Quellen aus drei Jahrtausenden", in:

Gabriel, G. I. et al., (editors), ”Was vom Himmel kommt: Stoffanalytische Zugänge zu Antiken Mythen aus Mesopotamien, Ägypten, Griechenland und Rom”, (2021) Berlin, Munichand Boston, at pp. 309-407

Kesecker N. T., “Lugal-zagesi: the First Emperor of Mesopotamia?”, Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 12:1 (2018) 76-95

Steinkeller P., “The Birth of Elam in History”, in:

Álvarez-Mon J. et al. (editors), “The Elamite World”, (2018) Oxford and New York, at pp. 177-202

Steinkeller P., “History, Texts and Art in n Early Babylonia: Three Essays”, (2017) Boston and Berlin

Potts D. T., “The Archaeology of Elam: Formation and Transformation of an Ancient Iranian State; Second Edition”, (2016), New York and Cambridge

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I., “Part I: Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp.1-130

Oraibi A. H., “Gišša (Umm al-Aqarib), Umma (Jokha), and Lagaš in the Early Dynastic Period”, Al-Rafidan, Journal of Western Asiatic Studies, Tokyo, 35 (2014) 1–37

Monaco S. F., “Some New Light on Pre-Sargonic Umma”, in:

Feliu L. et al. (editors), “Time and History in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 56th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at Barcelona (26–30 July 2010)”, (2013) Winona Lake, IN, at pp. 745-50

Steinkeller P., “An Archaic ‘Prisoner Plaque’ From Kiš”, Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archéologie Orientale, 107 (2013) 131-5

Zólyomi G., “The Vase Inscription of Lugal‐zagesi and the History of his Reign”, Notes for a seminar held at the Institute for Advanced Studies, Budapest (2013)

Charvát P., “The Origins of the LUGAL Office”, in

Charvát P. and Mařiková Vlčková P. (editors), “Who Was King? Who Was Not King? The Rulers and the Ruled in the Ancient Near East”, (2010) Prague, at pp. 16-22

Marchesi G., “The Sumerian King List and the Early History of Mesopotamia”, in:

Biga M. G. and Liverani M. (editors.), “Ana Turri Gimilli: Studi Dedicati al Padre Werner R. Mayer da Amici e Allievi”, (2010) Rome, at pp 231-48

Glassner J.-J., “Mesopotamian Chronicles”, (2004) Atlanta GA

Richardson M. E. J., ‘Hammurabi's Laws: Translation: Text, Translation and Glossary”, (2004, 2nd edition) London and New York

Westenholz A., “The Sumerian City-State”, in:

Hansen M. H. (editor), “A Comparative Study of Six City-State Cultures: An Investigation Conducted by the Copenhagen Polis Centre”, (2002) Copenhagen, at pp. 23-42

Goodnick Westenholz J., “Legends of the Kings of Akkade”, (1997) Winona Lake, IN

Wilcke C., “Amar-girids Revolte gegen Narām-Suʾen", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie”, 87:1 (1997) 11-32

Cooper J. S. and Heimpel W., “The Sumerian Sargon Legend”, Journal of the American Oriental Society, 103:1 (1983) 67-82

Jacobsen T., “The Sumerian King List”, (1939) Chicago IL

Langdon S. H., “The H. Weld-Blundell Collection in the Ashmolean Museum: Vol. II: Historical Inscriptions, Containing Principally the Chronological Prism (WB. 444)”, (1923) London

References

del Bravo F., “The Diyala Region and the ‘Territorial State of Kish’”, in:

Ramazzotti M. (editor), “Costeggiando l’Eurasia: Archeologia del Paesaggio e Geografia Storica

tra l’Oceano Indiano e il Mar Mediterraneo: Primo Congresso di Archeologia del Paesaggio

e Geografia Storica del Vicino Oriente Antico (Sapienza Università di Roma, 5-8 Ottobre 2021)”, (2024) Rome, at pp. 297-314

Gabriel, G. I.,"The ‘Prehistory’ of the Sumerian King List and Its Narrative Residue", in:

Konstantopoulos G. and Helle S., “The Shape of Stories”, (2023) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 234-57

Wilson K. L. and Bekken D., “Where Kingship Descended from Heaven: Studies on Ancient Kish“, Chicago IL (2023)

Steinkeller P., “The Sargonic and Ur III Empires”, in:

Bang P. F. et al. (editors), “The Oxford World History of Empire (Volume 2): The History of Empires”, (2021) New York, at pp. 43-72

George A. R., “The Tamarisk, the Date-Palm and the King: A Study of the Prologues of the Oldest Akkadian Disputation", in:

Jimenez E. and Mittermayer C. (editors), “Disputation Literature in the Near East and Beyond”, (2020) Berlin and Boston, at pp. 75-90

Lecompte C., “A Propos de Deux Monuments Figurés du Début du 3e Millénaire: Observations sur la Figure aux Plumes et la Prisoner Plaque”, in:

Arkhipov I. et al, (editors), “The Third Millennium: Studies in Early Mesopotamia and Syria in Honor of Walter Sommerfeld and Manfred Krebernik”, (2020), Leiden and Boston, at pp. 417-46

Westenholz A., “Was Kish the Center of a Territorial State in the Third Millennium?—and Other Thorny Questions”, in:

Arkhipov I. et al. (editors), “The Third Millennium: Studies in Early Mesopotamia and Syria in Honor of Walter Sommerfeld and Manfred Krebernik”, (2020) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 686-715

Charvát P., “The Origins of the LUGAL Office”, in

Drewnowska O. and Sandowicz M. (editors), “Fortune and Misfortune in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 60th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at, Warsaw, 21–25 July 2014”, (2017) Winona Lake, IN, at pp. 193-200

Koubková E., “ Fortune and Misfortune of the Eagle in the Myth of Etana”, in

Drewnowska O. and Sandowicz M. (editors), “Fortune and Misfortune in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 60th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale at, Warsaw, 21–25 July 2014”, (2017) Winona Lake, IN, at pp. 371-82

Steinkeller P., “History, Texts and Art in Early Babylonia: Three Essays”, (2017) Boston and Berlin

Zaina F., “Tell Ingharra-East Kish in the 3rd Millennium BC: Urban Development, Architecture and Functional Analysis”, in:

Stucky R. A, et al. (editors), “Proceedings of the 9th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East”, (2016) Wiesbaden, at pp. 431-46

Marchesi G., “Toward a Chronology of Early Dynastic Rulers in Mesopotamia”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol. 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 139-58

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I., “Part I: Philological Data for a Historical Chronology of Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol. 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 1-130

Steinkeller P., “An Archaic “Prisoner Plaque” from Kiš”, Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archéologie Orientale, 107 (2013) 131-57

Dalley S. M., “Old Babylonian Prophecies at Uruk and Kish”, in:

Melville S. and Slotsky A. (editors), “Opening the Tablet Box: Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Benjamin R. Foster”, (2010) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 85-97.

Frayne D. R., “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Vol. 1: Presargonic Period (2700-2350 BC)”, (2008) Toronto

Lapinkivi P., “The Sumerian Sacred Marriage and Its Aftermath in Later Sources”, in:

Nissinen M. and Uro R. (editors), “Sacred Marriages: The Divine-Human Sexual Metaphor from Sumer to Early Christianity”, (2008) University Park, PA, at pp. 7-42

Magid G., “Sumerian Early Dynastic Royal Inscriptions”, in:

Chavalas M. W. (editor), “The Ancient Near East: Historical Sources in Translation”, (2006) Malden, MA and Oxford, at pp. 4-16

Margueron J.-C., "Mari and the Syro-Mesopotamian World", in:

Aruz J. and Wallenfels R. (editors), “Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium BC, from the Mediterranean to the Indus”, (2003) New York, at pp. 135-64

Steinkeller P., “An Ur III Manuscript of the Sumerian King List”, in:

Sallaberger W. et al. (editors), “Literatur, Politik und Recht in Mesopotamien: Festschrift fur Claus Wilcke”, (2003) Wiesbaden, at pp. 267-292

Postgate J. N., “Early Mesopotamia: Society and Economy at the Dawn of History”, (1994) Abingdon Frayne D., “Early Dynastic List of Geographical Names: American Oriental Series 74”, (1992) New Haven, CT

Cooper, J. S., “Reconstructing History from Ancient Inscriptions: The Lagash-Umma Border Conflict”, (1983), Malibu CA

Maeda T., “‘King of Kish’ in Presargonic Sumer”. Orient, 17 (1981 ) 1-17

Moorey P. R. S., “Kish Excavations (1923-1933)”, (1978) Oxford