Empires of Mesopotamia:

Lagash: Temple(s) of Ningirsu

Empires of Mesopotamia:

Lagash: Temple(s) of Ningirsu

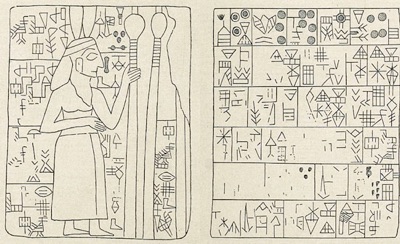

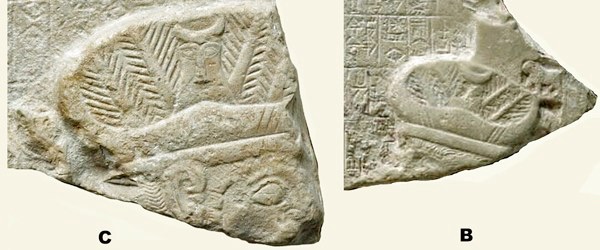

Inscribed stone plaque from the site of the Temple of Ningirsu at Girsu

depicting the so-called ‘Figure aux Plumes’ (Figure with Feathers)

Now in the Musée du Louvre (AO 221); image from the museum website

As Sébastien Rey (referenced below, 2024, at p. 6) pointed out, although Ningirsu was the city-god of Lagash (modern al-Hiba), his name means ‘Lord of Girsu’. Furthermore, his temple was at Girsu (modern Tello), some 25 km to the west, which seems to have served as its ‘religious capital’ of Lagash from the time of the foundation of what was actually an extended city-state. Ernest de Sarzec discovered the site of Girsu in the late 1870s, when, as Rey observed (at pp. 10-11) observed, the excavation of structures on what is now known as Tell K:

“... turned out to be a series of shrines containing abundant religious accessories dedicated to Ningirsu that dated from around 3000 BC to 2300 BC. The first explorers [here] had brought to light parts of the earliest temple complex devoted to the tutelary deity of Girsu, who was the divine proprietor of Lagash ... [within] an expansive religious precinct [that] was constructed on a large artificial mound made of mud bricks, [so that it] was significantly raised above the surrounding flood plain.”

It became clear during the subsequent excavations that Tell K was the site of two separate temples:

✴the first (which was dubbed to ‘Lower Construction’) seems to have been founded ca. 3000 BC; and

✴the second, which was built above it some 500 years later by Ur-Nanshe, the earliest-known independent ruler of Lagash, was razed to the ground in ca. 2300 BC, when this ‘Lagash I’ dynasty came to an end.

Archaic Temple of Ningirsu

Plaque Depicting the ‘Figure with Feathers’

Sketch of both sides of the plaque depicting the ‘Figure with Feathers’ (see above)

Adapted from Ernest de Sarzec (referenced below, XXXV)

The plaque illustrated at the top of the page and in the sketch above is one of the oldest objects discovered on Tell K: as Sébastien Rey (referenced below, at p. 181) observed, although the archeological context in which it was found is obscure:

“There is no doubt ... that it was originally housed in the ‘Lower Construction’ and was probably fashioned to commemorate [its] construction and inauguration.”

He dated both the ‘Lower Construction’ itself and the putative ‘foundation’ plaque to 2900-2800 BC, although he acknowledged that other datings have beed suggested: for example, Camille Lecompte (referenced below, at p. 432) dated the inscription on the plaque (on palaeographic grounds) to 2750-2700 BC. One side of the plaque (usually dubbed the obverse) carries a shallow relief in which a male figure wearing distinctive headgear approaches an entrance defined by a pair of monumental maces. Rey argued that:

✴this figure represents Ningirsu himself and the maces mark the threshold to his temple (see p. 178); and

✴although the position of his hands relative to the maces is hard to establish, the likelihood is that he gestures with his free left hand toward this threshold (see p. 174).

One of the most distinctive features of this image is the nature of Ningirsu’s headgear: as Sébastien Rey (referenced below, at p. at 175) observed:

“As soon as the [relief] was found, [this headgear] was interpreted ... as a crown with two large feathers ... Although this interpretation has been questioned, ... it is almost certainly the right one. ... The similarity between the chevron-like form of:

✴the ... feathers [of the lion-headed bird] on the top surface of the [much later mace-head of Mesalim - see below]; and

✴the decorative features of the headdress [of this figure of Ningirsu];

is particularly striking.”

In other words, since the feathers depicted on Mesalim’s mace clearly belong to a bird, then the likelihood is that the very similar ‘decorative features’ on Ningirsu’s headdress are also bird feathers. Camille Lecompte (referenced below, at p. 435) also concluded from similar comparisons that:

“The headgear [of Ningirsu] could ... well turn out to be composed of feathers”, (my translation).

This does not necessarily mean that the feathers on Ningirsu’s headdress would have been ‘read’ as those of a lion-headed bird, although, as Rey pointed out (at p 176), it would be:

“... no surprise [if] the sculptors of the [this relief] drew on [an] inextricable link between Ningirsu and the [lion-headed bird] that went back to the most archaic times.”

The archaic cuneiform inscriptions on the plaque (which Sébastien Rey translated at pp, 176-7) are, unsurprisingly, difficult to understand in detail:

✴that on the obverse, which surrounds the figure of Ningirsu, apparently recounts a creation myth; and

✴that on the reverse (which contains only text) is split into two parts:

•an inventory of plots of land; followed by

•a hymn of praise to Ningirsu.

He summed up (at p. 177 ) as follows:

“This ... extraordinary and unique text ... is one of the oldest recorded literary compositions in human history. Falling into no known or clearly defined generic category, it is, at one and the same time:

✴a sacred temple hymn;

✴a creation myth;

✴a song of praise;

✴an inventory of [Ningirsu’s] fields, orchards and pasture lands; and

✴a document relating to the distribution of the wealth that the estates produce.

At its heart is the god Ningirsu and his house (é.Ningirsu), which clearly connotes the temple as well as his institution at large.”

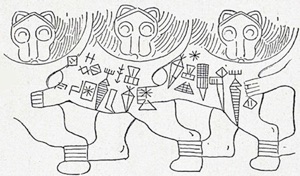

Mace Head of Mesalim

Inscribed mace head of Mesalim, King of Kish (RIME 1.8.1.1; P462181),

from the site of the Temple of Ningirsu at Girsu, now in the Musée du Louvre (AO 2349)

Images from the museum website

The object illustrated above is another object discovered on the site of the temple on Tell K that (as we shall see) must have been dedicated in the ‘Lower Construction. Sébastien Rey (referenced below, 2024, at p. 209) characterised it as:

“... an oversized and therefore symbolic limestone votive mace head ... that is decorated with reliefs ...”

He described the figure on the flat, un-pierced upper surface as:

“... a lion-headed eagle with outstretched wings.”

As we shall see, this is the earliest-known representation of a motif that subsequently became emblematic for the independent rulers of Lagash. The frieze that runs around the curved surface below contains the figures of six half-erect leaping lions, each of which seems to be to be chasing and grasping the one in front of it.

Sketch of two of the six lions in the frieze around the mace head of Mesalim (see above)

Adapted from Ernest de Sarzec (referenced below, XXXIV)

Importantly, the short cuneiform inscription carved across two of these lions reads:

“Mesalim, king of Kish, temple builder for the god Ningirsu, (dedicated ?) this mace to/for the god Ningirsu [when] Lugal-sha-engur (was) ensi of Lagash”, (RIME 1.8.1.1; P462181).

In other words, Mesalim, king of Kish, effectively rebuilt (or, more probably, extensively restored) the archaic temple of Ningirsu at Girsu as hegemon, when the otherwise unknown Lugal-sha-engur exercised delegated authority (as ensi of Lagash), an event that he commemorated by dedicating this mace-head to Ningirsu. Furthermore, we might reasonably assume that, by this time, ‘Lagash’ represented a polity that included both Lagash itself (at modern Tell al-Hiba) and Girsu: Sébastien Rey (referenced below, at p. 150) tentatively dated the mace-head to ‘some time between 2600 and 2500 BC’.

This inscription should be considered alongside Mesalim’s other two surviving inscriptions, both of which come from the Esar temple at Adab (between Kish and Lagash):

✴One, which was found on fragments of two stone bowls, records that:

“Mesalim, king of Kish, sent over this bur mu-gi4 (stone bowl, used for the burgi ritual) in the E-SAR [when] Nin-KISAL-si (was) ensi of Adab”, (RIME 1.8.1.2; P462182).

✴The other, which was found on the inside of the upper part of a decorated chlorite vase, records that:

“Mesalim, king of Kish, beloved son of Ninhursag [dedicated this vase ??] ...”, (RIME 1.8.1.3; P431033).

Although some scholars (see, for example, Douglas Frayne, referenced below, 2008, at p. 20) suggest that this temple was dedicated to Inanna, Karen Wilson (referenced below; see, for example, Table 9.1, at p. 100) has shown that the archeological evidence (which includes that from Mesalim’s vase) indicates that it was dedicated to Ninhursag (who is sometimes named as Dingirmah). Taken together, these three inscriptions show that, as Nicholas Postgate (referenced below, at p. 30) observed:

✴both:

•Lugal-sha-engur, ensi of Lagash; and

•Nin-kisal-si, ensi of Adab;

acknowledged the hegemony of Mesalim, king of Kish; and

✴he made a point of honouring the deities who ‘owned’ their respective city-temples.

A much later ruler of Lagash, Enmetena (see below), looked back on Mesalim’s role in the establishment of the border between Lagash and Umma:

✴“Enlil, lugal kur-kur-a (king of all lands), ab-ba dingir-dingir-re2-ne-ke4 (father/elder of all the gods) ... demarcated the border between Ningirsu and Shara [the city god of Umma]. Mesalim, king of Kish, at the command of [the god] Ishtaran, demarcated this border and erected a stele there”, (RIME 1.9.5.1; P431117, lines 1-12).

✴It is clear from these later testimonies that Mesalim’s authority as hegemon extended to Umma, and that his role in the establishment of the boundary between Lagash and Umma was long-remembered, at least at Lagash. Interestingly, Enmetena (and hence, presumably, Mesalim):

✴regarded Enlil, the city-god of Nippur as the ‘father/elder of all the gods’; and

✴naturally assumed that he had authority over the lesser gods Ningirsu and Shara in the matter of the location of the border between their respective territories (albeit that he delegated the matter of the execution of his commands to Ishtaran). As Aage Westenholz (referenced below, 2020, at p. 696) observed:

“Mesilim is said to have acted in accordance with the [command of] ... Ishtaran, [who] was the divine protector of treaties, as indicated by the spelling of his name dKA.DI (god of just verdict).”

As I discuss further below, it is therefore possible that the iconography of the mace-head that he dedicated to Ningirsu at his temple in Girsu should be understood as a composite, in which:

✴the lion-headed eagle represented Enlil; and

✴the lions in the frieze below represented Ningirsu.

Ningirsu’s Temple During the Lagash I Dynasty

Temple of Ur-Nanshe

Political Context

As we have seen:

✴Mesalim almost certainly dedicated the mace-head discussed above to Ningirsu in the ‘Lower Construction’, the archeologists’ term for the archaic temple that pre-dated that built by Ur-Nanshe; and

✴by this time, it seems that:

•the political union between Girsu and Lagash was already established;

•Ningirsu, the ‘Lord of Girsu’, was regarded as the most important god in the ‘consolidated’ pantheon; and

•Enlil, the city-god of Nippur, was regarded as the ‘father/elder of all the gods’, including Ningirsu.

However, as Sébastien Rye (referenced below, at p. 152) observed, although the union of Lagash and Girsu was in place by the time of Mesalim, Ur-Nanshe should be credited with the creation of coherent and stable political entity that extended from the inland border with neighbouring Umma to the maritime district of Gu’abba on the Lower Sea. Furthermore:

“Perhaps even more importantly:

✴[Ur-Nanshe] created a new religious framework for the new merged state, [which now also included Nigin], that was absolutely crucial for its survival and sustainability; and

✴[this] reformed religious structure was centred [on] the pantheon that was headed by Girsu’s chief god, Ningirsu ...”

As Rey also observed: :

✴“The centrepiece and starting point for the entire scheme was the splendid new Temple of Ningursu at Tell K ...”, (see pp. 212-3); and

✴“The re-establishment of the state’s most sacred precinct [here], including the ritual interment of the ‘Lower Construction’ [under massive mud-brick structure that served as a platform for the new temple complex], [together with the] desacralisation and ceremonial burial of its holiest artefacts, can also be understood in the context of Ur-Nanshe’s comprehensive politico-religious transformation”, (see p. 217).

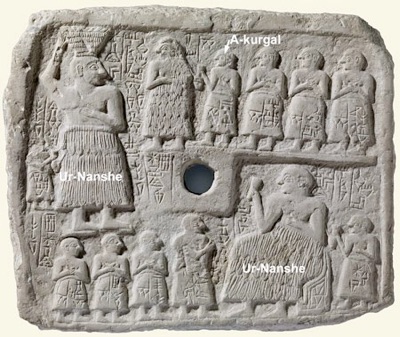

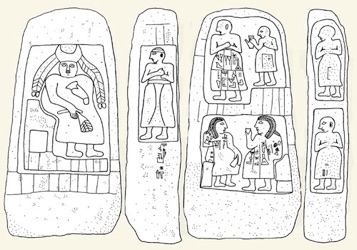

Ur-Nanshe’s ‘Genealogical’ Plaques

Pierced relief of Ur-Nanshe from the temple on Ningirsu that he built at Girsu (RIME 1.9.1.2. P431035)

Now in the Musée du Louvre (AO 2344); image from museum website

The pierced limestone relief illustrated above is the best-preserved of four ‘genealogical’ plaques of Ur-Nanshe that were (or were probably) found on the site of this temple. They are so-called because they depict Ur-Nanshe alongside other figures, all identified by inscription, most of whom are members of his immediate family (which included at least nine sons: Akurgal, who succeeded him; Addatur; Anikurra; Anita, who was apparently also his cup bearer; Anupa; Gula; Lugalezen; Menu; and Mukurmushta). Sébastien Rey illustrated all four of them as Figure 89 (at p. 231), with the one illustrated here as his example A:

✴the inscription on ‘example A begins:

“Ur-Nanshe, lugal (king) of Lagash, son of Gunidu, son of [a place called] Gursar, built the é.dnin.gir.su (House of Ningirsu)”, (RIME 1.9.1.2. P431035, lines 1-6; and

✴the other three examples carried the same inscription, except that none of them named Ur-Nanshe’s birthplace, Gursar.

Interestingly, in naming his new temple, Ur-Nanshe preserved the name that had been given to the ‘Lower Construction’ at its foundation, as evidenced by the inscription on the ‘Plaque of the Figure with Feathers’. He is illustrated twice in ‘example A’:

✴one in the upper register, where he carries a basket of bricks on his head (a motif that is repeated in Rey’s example D); and

✴in the lower register, he is enthrone and raises a beaker in his right hand.

It seems likely that the ‘crown of bricks’ symbolises Ur-Nanshe’s building of the new temple, and that the beaker suggests an inaugural libation or celebration.

Pierced relief of Ur-Nanshe (RIME 1.9.1.26, P431061), now in the Musée du Louvre (AO 2783)

Image from museum website

The object illustrated above is one of what Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, at p. 112) described as:

“Three very similar wall plaques of Ur-Nanshe from Girsu, [all of which] depict an Anzu bird standing on two lions.”

The inscription (RIME 1.9.1.26, P431061) on this example reads:

“For Ningirsu: Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash, son of Gunidu, built the E-Tirash.”

Frayne (as above) argued that:

“While only part of the titulary of Ur-Nanshe is preserved on the other two plaques, they very likely bore the same or a similar inscription.”

As discussed above, King Mesalim of Kish had used essentially the same iconography on the mace that he had dedicated to Ningirsu at Girsu, apparently as overlord in the time of Lugal-sha-engur, ensi of Lagash. I discuss this iconographic tradition below.

As Frans Wiggermann (referenced below, at p. 159) observed:

“Composite emblems consisting of [various animals in pairs] with an Anzu stretching out its wings above them are attested for a number of gods [throughout Sumer].”

“The composite emblem ‘lions plus Anzu’ is extremely rare outside Lagash ...”

Thus, we might reasonably assume that:

the two ‘lion plus Anzu emblems’ on the vase that Enmetena dedicated to Ningirsu at his temple in Girsu were closely associated with Ningirsu; and

each of the other two ‘Anzu’ emblems on the vase was similarly associated with another Sumerian deity that was associated with the ibex or the stag.

In this context, he recorded (at p. 160) that:

a copper relief (ca. 2500) from the Temple of Ninhursag at Tell Al-‘Ubaid, outside Ur, which is now in the British Museum (exhibit BM 114308), depicts an Anzu above a pair of stags that he characterised as ‘the symbolic animals of the goddess’;

Eanatum

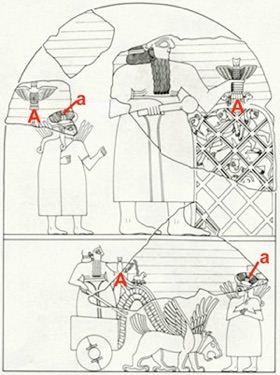

‘Stele of the Vultures’

Surviving fragments from the obverse of the two-sided ‘Stele of the Vultures’ from the Temple of Ningirsu at Girsu,

now in the Musée du Louvre (AO 50): images from the museum website (my additions in black)

The important ‘Stele of the Vultures’ (illustrated above) is known from seven fragments (A-G, exhibited in the Musée du Louvre as AO 50) of what was originally a huge limestone stele:

✴fragments A-F were excavated at the site of the Temple of Ningirsu at Girsu; and

✴fragment G, which clearly belonged to this stele, subsequently emerged in London and was re-united with the other fragments in Paris.

All of these fragments carry reliefs and inscriptions on both sides. As Renate Marian van Dijk-Coombes (referenced below, at pp. 198-9) observed, when these fragments were laid out in what would have been their respective positions, it became obvious that the stele had what might be dubbed:

✴a historical side that is divided into four registers, in which the reliefs illustrate a battle and its aftermath; and

✴a mythological side (see the illustration above), in which the reliefs depict the imagined actions of the two deities thereafter.

The inscription on each of the vertical edges identifies:

“Eanatum, kur gu2 gar-gar (the subjugator of the lands of Ningirsu)”, (lines 630’-632’ and 633’-635’).

The stele owes its modern name to the relief on the reverse of Fragment A, which depicts a flock of vultures carrying off the remains of fallen enemy soldiers (which would have represented the final scene in the ‘historical’ sequence).

✴in the upper register;

•the large male figure standing at the centre (who holds a mace in his right hand and a battle-net full of naked prisoners of war in his left hand) is almost certainly Ningirsu; and

•the small head of the figure behind him (who stands in front of a battle standard) belonged to a goddess who had weapons (usually identified as maces) ‘emerging from the shoulders’, who is ‘Ninhursag or possibly Inanna’; and

✴in the lower register:

•the chariot was probably driven by Ningirsu (albeit that only part of his skirt now survives); and

•the small head to the right probably belonged to the same goddess as the one in the upper register.

A third important iconographical figure of this side of the stele is the so-called Anzu bird, which appears in:

✴in at least three places (marked A in the drawing above), as an emblem of some sort on:

•a battle standard;

•the top of Ningirsu’s battle-net; and

•adorning his chariot; and

✴as a lion’s head surrounded by feathers in the so-called ‘Anzu crown’ of both. figures of the goddess (marked a in this drawing).

As we have seen, this figure:

✴may have been reflected in the archaic ‘Feathered Figure Plaque’; and/or

✴was certainly represented on two earlier objects from Lagash/Girsu:

•the mace of Mesalim; and

•the so-called ‘Plaque of the Anzu Bird’ of Ur-Nanshe.

I discuss the identity of the goddess wearing the ‘Anzu crown’, the iconographical significance of the Anzu bird and its association with Ningirsu below.

The inscription (RIME 1.9.3.1, P431075) that surrounds the figures on both sides of the stele deals principally with a border dispute between Lagash and Umma. It begins on the obverse of fragments A, D and C. Only a single isolated phrase survives from the opening passage:

“... he reduced its subsistence rations, he reduced its grain rent”, (lines 1’-4’).

As we shall see from what follows, we might reasonably assume that ‘he’ was the ‘Man of Umma’, and that he was deemed to have broken the terms of a commercial undertaking between Umma and Lagash. This is followed by a broken but reasonably coherent passage:

“The king of Lagash ... the Man of Umma committed an aggressive act ... and [approached ?] the frontier of Lagash. Akurgal, king of Lagash, the son of Ur-Nanshe, king of Lagash ...’’, (lines 5’-20’).

Thus, it seems that, after a period of increasing tension, Akurgal led the army of Lagash against the invading army of Umma (apparently while his father was still alive). The following text is again broken, but it seems that Akurgal succeeded in bringing the situation under control.

The next episode begins (at line 21’) when the Man of Umma re-opens hostilities, causing Ningirsu to exclaim into the wind that this sacrilegious mortal is threatening:

“... my own possessions in the field of the Gu'edena”, (lines 32’-37’).

Faced with this defiance:

“... Ningirsu ... implanted the semen for Eanatum in the womb ... [and] rejoiced over him.

✴Inanna stood beside him and named him ‘[the one who is] fitting for the Eanna of Inanna of the Ibgal’.

✴Inanna set him on the right knee of Ninhursag, [who] suckled him.

✴Ningirsu rejoiced over Eanatum.

✴Ningirsu, the one who had implanted his semen in the womb, laid his ... [gigantic hand] upon him.

Ningirsu, with great joy, [granted him] nam-lugal (the kingship) of Lagash”, (RIME 1.9.3.1, P431075, lines 40’-82’).

In short, in order to deal with the latest outrage from Umma, Ningirsu miraculously:

✴ensured the birth of a hero who is:

•named (as Eanatum) by Inanna; and

•suckled by Ninhursag; and

✴grants him the kingship of Lagash.

After much repetition of Eanatum’s divine credentials and his cursing of the sacrilegious ensi of Umma, Ningirsu appears to him in a dream:

“As Eanatum lay sleeping, his beloved king, Ningirsu, came to stand by his head ... [and told him that]:

‘Umma, like Kish, shall ... wander about and, by means of ones seized by anger(?), shall surely be removed. ... I shall smite [the enemy soldiers] and make their myriad corpses stretch to the horizon. ... [The people of Umma] shall raise a hand against [their leader] and, in the heart of Umma, they shall kill him. Ush/Ushurdu] by name ...”, (lines 121’-152’).

This suggests that Kish was allied with Umma and that Ningirsu promised Eanatum that this allied army was doomed to defeat, and that the ensi of Umma would be killed by his own subjects (which is presumably what happened, although the actual account of the battle at lines 153’-168’ is too lacunose for us to be sure). We then read that, after the promised victory:

“Eanatum, a man of just words, marked off the border territory, which [or some of which ??] he left under the control of Umma, [and he] erected a stele in that place”, (lines 169’-176’: see also the translation by Jerrold Cooper, referenced below, at p. 45.]

We then read that::

“[Eanatum then] defeated the Man of Umma ... and heaped up 20 burial mounds there [on the boundary mound named Namnunda-kigara ??]”, (lines 177’-181’);

Jerrold Cooper argued (referenced below, at p.26) argued that this probably indicates that fighting with Umma resumed later in Eanatum’s reign, and that he claimed a second victory. Finally. in this part of the text, we read that:

“Eanatum obliterated many foreign lands for Ningirsu. He returned to Ningirsu the Gu’edena, his beloved field”, (lines 187’-194’).

In the rest of the text on the obverse and at the start of the text on the reverse, Eanatum forces the Man Umma to swear on the battle nets of a series of deities that he would respect the terms of an agreement as to the location of the border and the use of the border territories, after which he sent messenger doves to relate the agreed term to:

✴Enlil, king of heaven and earth, at the Ekur in Nippur (lines 263’-267’);

✴‘my mother’, Ninhursag at Kesh, (lines 315’-318’);

✴Enki, king of the Abzu, (lines 368’-372’);

✴Sin, ‘my king’, the impetuous calf of Enlil, lines 428’-438’); and

✴Utu, king of vegetation, at the Ebabbar at Larsa, (lines 488’-490’).

This is followed by another ‘divine pedigree’, followed by a list of other military successes:

“Eanatum, king of Lagash:

✴given strength/power by Enlil;

✴fed wholesome milk by Ninhursag;

✴given a good name by Inana;

✴given wisdom by Enki;

✴chosen by the heart of Nanshe, the powerful mistress;

✴kur gu2 gar-gar (the subjugator of the lands of Ningirsu);

✴the beloved of Dumuzi-Abzu;

✴nominated by Hendursag;

✴beloved friend of Lugaluru;

✴beloved husband of Inanna;

defeated:

✴Elam and Subartu, the lands of timber and goods;

✴now-unknown locality;

✴Susa;

✴Arawa/Urua, [even though ?] its ruler had set up its standard at the head [of its army ?];

✴ [several lines missing];

✴Arua, which he obliterated; [and ?]

✴the [leader of ??] k-ien-gi (= Sumer ?), Ur ...”, (lines 564’-605’).

(It is unclear why Eanatum uses the title lugal in this inscription, rather than the usual title ensi.)

Interestingly, Kish is also referred to on one of the surviving fragments of this stele: we read that, as Eanatum lay sleeping, ‘his beloved king, Ningirsu’ appeared to him in a dream to reassure him that:

“Umma, like Kish, shall therefore wander about, and by means of ones seized by anger(?), shall surely be removed”, (obverse, lines 124’-136’).

This seems to suggest that Kish was allied with Umma at this time, which might explain why (according to the Eanatum Boulder):

✴Kish subsequently ‘trembled before’ Eanatum; and

✴Inanna, who loved him, ‘gave him the kingship of Kish’.

In this context, we should also consider another inscription of Eanatum (RIME 1.9.3.10, P431085), which is on a fragmentary vase from Lagash that is now apparently in the Iraq Museum) records Eanatum’s construction of a structure for Ningirsu that he dubbed the E-za (Stone House):

“For the god Ningirsu, warrior of the god Enlil: Eanatum, ensi of Lagash:

✴á-sum-ma (granted power by) Ningirsu;

✴[the one] who restored to Ningirsu his beloved Gu’edena;

✴[the one] who subjugates the lands for Ningirsu;

... built the E-za (Stone House) for the god Ningirsu out of silver and lapis lazuli. He [also] built for him a storehouse, a building of alabaster stone, and amassed piles of grain for him (there). Eanatum:

✴[the one to whom] Ningirsu granted the gidru (sceptre).

His personal god is Sul-MUSHxPA.”

Eanatum and Inanna

Details of fragments B and C of the ‘Stele of the Vultures’ (illustrated above) showing the head of a goddess

Now in the Musée du Louvre (AO 50): images from the museum website

Image of goddess with similar iconography to the goddess on the ‘Stele of the Vultiures’

Now in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin (VA 7248): image from website of the Morgan Library

As we have seen, Renate Marian van Dijk-Coombes (referenced below, at p. 201) argued that the goddess depicted in both of the registers on the obverse of the ‘Stele of the Vultures’ (fragments B and C, illustrated above) is probably Ninhursag or possibly Inanna (and she pointed out, at note 8, that she is sometimes identified as Nisaba). The relevant iconographic evidence for this identification is provided by the two other reliefs that are illustrated above:

✴that on one side of an inscribed limestone stele from Lagash that is now in the Iraq Museum (IM 61404), which dates to the reign of Ur-Nanshe, Eanatum’s grandfather; and

✴that on a fragment of an inscribed stone vessel that is now in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin (VA 7248), which almost certainly came from Lagash or Girsu and dates to the reign of Enmetena, Eanatum’s nephew.

Ur-Nanshe is depicted on the other side of the first stele. identified by inscription (RIME 1.9.1. 6a, P431039) as:

“Ur-Nanshe, son of Gu-NI.DU), ensi of Lagash, [the one who] built the Ibgal (= great oval temple of Inanna at Girsu).”

He is accompanied on this face of the by a cup=bearer and, below them, his wife and daughter, all identified by inscription. Most of the other inscriptions on both sides of the stele are now lacunose and largely illegible, although the first line duplicates the inscription identifying Ur-Nanshe as the builder of the Ibgal, which suggests that the enthroned goddess depicted on the opposite side in Inanna. Giovanni Lovisetto (referenced below, at p. 55) observed that she:

“... holds a branch of dates [in her right hand] and possibly a cup, while her extraordinarily long and voluminous hair falls from a (possibly horned) headdress over her shoulders.”

The inscription (RIME 1.9.5. 25, P431142) on the Enmetena vase reads:

“... he [= Enmetena] built E-engur of Zulum for [the goddess Nanshe: he built Abzu-pasira for the god Enki, king of Eridu; [he built the giguna [for] goddess Ninhur[sag]; ... when ... had been granted [presumably by a goddess], he, [Enmetana] set up (this) bur-sag vessel for her.”

Inanna is mentioned in some of the surviving fragments of the inscribed text:

✴as Pirjo Lapinkivi (referenced below, at p. 20) pointed out, Eanatum is referred to as the dam kiag2 (beloved spouse) of Inanna (at reverse, lines 586’-587’); and

✴she is also referred to (at obverse, lines 56’-60’) as:

“Inanna, [who] ... named -Eanatum] as:

‘[the one who is] fitting for the E-anna of Inanna of the Ib-gal (‘great oval’ [temple])”.

This is a reference to a temple excavated at at Lagash that had an outer oval-shaped walled court, which is known from inscribed foundation figurines as the Ibgal of Inanna (see, for example, Paul Collins, referenced below, at p. 105).

It is difficult to know what Eanatum gained from these many and widespread victories recorded in these inscriptions: while we can imagine that they brought him both booty and prestige (and perhaps the right to tribute and military conscripts on an on-going basis), the extent of his political influence over the conquered cities is unclear. As noted above, Aage Westenholz (referenced below, 2020, at pp. 697-8) argued that Eanatum’s victories over cities that were far from Lagash does not prove that he established anything approaching a Sumerian state, centred on Lagash. While this is certainly true, it does seem to me that Eanatum’s claim that:

✴Inanna had given him the kingship of Kish; and

✴Kish had ‘trembled before him’;

does suggest that he had established hegemony over Kish for a period after his victory. Indeed, it is tempting to suggest that sought to present himself as a ‘new Mesalim’. Nevertheless, it seems that any such eminence was short-lived, since nothing in the surviving evidence suggests that any subsequent ruler of Lagash claimed the title ‘king of Kish.

Sketch of the relief on a mace-head dedicated for the life of Enanatum (RIME 1.9.4,14, P431115)

The mace-head, which probably came from Girsu, is now in the British Museum (BM 23287)

The sketch is from Jean Evans (referenced below, Figure 28, Cat. 35, at p. 76)

The sketch illustrated above summarises the iconography on a mace head that carries an iscription that reads as follows:

“To Ningirsu of the E-ninnu [sanctuary of Ningirsu at Girsu]: the workman of Enanatum, ensi of Lagash, named) Barakisumun (who was) the minister (sukkal), dedicated (this mace-head) for the life of Enanatum his master”.

Douglas Frayne (referenced below, at p. 191) assigned this object to the reign of Enanatum I, the grandson of Ur-Nanshe, who had succeeded his brother, Eanatum. Jean Evans (referenced below, at p. 76) suggested that the largest of the three figures who approach the Anzu bird from its right is probably Barakisumun and noted that he is followed by a two smaller figures, one carrying a vessel for libation and the other clasping a large staff. Sébastien Rey (referenced below, at p. 176) argued that in this iconography, offerings are brought to the Anzu bird, who therefore explicitly acts as Ningirsu’s avatar.

Evans J., "Mace-head Dedicated for the Life of Enannatum", in:

Aruz J. and Wallenfels R. (editors), “Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium BC, from the Mediterranean to the Indus”, (2003) New York, at pp. 85-6

Note Eanatum received the sceptre from Ningirsu

Silver vase of Enmetena, ensi of Lagash, from the temple of Ningirsu at Girsu,

now in the Musée du Louvre (exhibit AO 2674)

Drawing of the central image above and those that flank it, from the website of ‘Old European Culture’

The second point to make is that the earliest surviving written evidence from Lagash that gives this creature a name and provides specific information about its iconographical meaning dates to the time of the second independent dynasty of Lagash (more than 200 years after the end of the first, in the window of about a century between the Akkadian and the Ur III empires).

First, we should address the confusing matter of the name of this hybrid creature. Sébastien Rey (referenced below, at p. 5) referred to it as:

“... Imdugud (or Anzu), the radiant Thunderbird himself”;

and it is often asserted that Imdugud and Anzu represent its name in Sumerian and Akkadian respectively. Thus, for example, Anne Rebekka Øiseth (referenced below, at p. 28) referred to:

“The terrifying Imdugud bird, usually translated as Thunderbird (and also commonly referred to by its Akkadian name Anzu) ...”

However, as Herman Vanstiphout (referenced below, note 33, at p. 18), for example, observed that:

“The reading of the name of this supernatural bird is still a matter of controversy among specialists.”

His primary concern was with the Sumerian text known as the ‘Matter of Aratta’, which probably dates to the Ur III period, ca. 2100–2000 BC, in which:

“... it is written consistently as IM.DUGUD (‘heavy (storm) cloud’), so that ‘Thunderbird’ seems to be an adequate translation. Still, the consensus is now that it was read as [Anzu(d)], with no known etymology or explanation. In reading ‘Anzud’ [in this translation], I bow to the collective wisdom and arguments of the majority, but I remain convinced that the scribes were thinking of a heavy storm cloud every time they wrote the signs.”

Chikako Watanabe (referenced below, at p. 33), who explicitly avoided ‘the philological argument around the name Imdugud/Anzu observed that it:

“... consists of four signs: AN. IM. DUGUD. and MUSHEN meaning literally:

‘the bird (mushen) of heavy cloud/fog (im.dugud = imbaru ) in the sky (an)’;

which suggests a close association with thick cloud.

In what follows, I shall simply use the word ‘Anzu’ and refrain from relying on philology in the quest to understand what this creature signified in Lagash in the 3rd millennium BC.

As we shall see, although the surviving evidence indicates that many of the other kings of the first dynasty of Lagash (besides Enmetena) commissioned images of the Anzu, its symbolic importance at Lagash and Girsu both pre-dated and post-dated them. For example:

✴King Mesalim of Kish (who exercised hegemony over Lagash and Girsu before the emergence of the first independent dynasty of this city-state) commissioned a ceremonial mace for the temple of Ningirsu at Girsu on which the Anzu was prominently depicted; and

✴Gudea (who belonged to the second dynasty of Lagash) made several references to the Anzu in his commemorations of his rebuilding of this temple.

I discuss all of this evidence in detail below: for the moment, we should note that Enmetana’s silver vase is particularly important for our present analysis because it contains no fewer that four complete images of the Anzu, hovering above pairs of three different animals:

✴twice above a pair of lions (once on the surface shown above and once on the surface behind it);

✴once above a pair of ibexes (to the left in the drawing above); and

✴once above a pair of stags (to the right in the drawing).

These images therefore offer a particularly useful starting point for our analysis of the way in which the Anzu was perceived at Lagash in the middle of the 3rd millennium in BC.

He also noted that:

the stags under an Anzu on the relief from the Temple of Ninhursag at Ur] are the symbolic animals of that goddess (Gudea CyL B X 4, Frg. 5 ii, cf. Heimpel RIA 4 420).

[the] ibex belongs to Enki, who is called dàra-kù- abzu (Gudea Cy/ AXXIV21) and dDàra-abzu (TCL XV10:77,cf.

Green Eridu 194).

The point here is that, as he summarised (at p. 161):

“The Anzu ... is not Ningirsu's symbol, nor that of any of the other gods with whose symbolic animal it is combined. It represents another, more general power, under whose supervision they [i.e., the symbolic animals of particular deities] all operate. This higher power can only be Enlil, [= the chief deity of the Mesopotamian pantheon at this time].”

Interestingly, each of the four lions on the vase is shown attacking the adjacent ibex or stag. Sébastien Rey (referenced below, at p. 296) suggested that this might have been meant to convey:

“...the power that Lagash wielded over [the localities represented by the ibexes and the stags], with the dominant [Anzu] stressing that the exercise of such power is subject to the god’s favour, as is the city-state’s on-going prosperity.”

If we combine this hypothesis with that of Frans Wiggerman, then the iconography on the vase would have represented the power that Ningirsu and Enmetena, as delegates of Enlil, wielded over the localities represented by the ibexes and the stags. It seems to me that the geographical locations of these localities might be found in the inscription (RIME 1.9.3.1, P431075) on the so-called ‘Stele of the Vultures’, which was commissioned by Enmetena’s uncle, Eanatum, to commemorate his victory in a border dispute with his neighbours at Umma:

✴we read here that, after this victory, Eanatum obtained an oath of compliance from the vanquished ‘Man of Umma’ that was sworn on by the lives of Enlil, Ninhursag, Enki and three other deities; and

✴copies of the first three of these oaths were sent by carrier pigeon to, respectively:

•Enlil, king of heaven and earth, in the Ekur at Nippur (lines 263’-267’);

•Ninhursag, his mother, at Kesh (lines 315’-319’); and

•Enki, king of Abzu, at Abzu, which probably indicates Eridu (lines 359’-372’).

However, I acknowledge that there is no supporting evidence that Enmetena ever held power over either Kesh or Eridu.

that

This figure takes its name from an Akkadian legend in which Ningirsu killed the Anzu bird.

However, since this legend is known from only two texts from Susa that date to the Old Babylonian Period (ca. 2000 BC), we cannot simply assume that the this text corresponds directly to the oral tradition that must have been reflected in the iconography some 5-7 centuries earlier. For example, Chikako Watanabe (referenced below, at p. 32) has recently analysed the evolution of the iconography of the lion-headed eagle in early Mesopotamia:

“The lion-headed eagle, which comprises a bird of prey with the head of a lion, appears in the earliest pictorial representations shown in seal impressions which date back to the Uruk period. In this early period, the creature is represented in profile flying over captured enemies with wings stretched upright and head lowered; ... During the Early Dynastic period the lion-headed eagle was depicted in frontal view with wings and legs spread wide to stand over a pair of animals, such as

✴ibexes;

✴stags; or

✴lions.

The creature is also depicted on the ‘Stele of the Vultures’ together with a pair of lions’ heads, which are represented below the lion-headed eagle, on top of a net. The net contains naked enemies of Girsu; a large male figure grasps the tail feathers of the lion-headed eagle.”

Chikako Watanabe (referenced below, at p. 34) observed that:

“From the beginning of the 2nd millennium, the storm god is shown more closely associated with another of his animal attributes, the bull. T he lion dragon represents Anzû independently, and was at first depicted as a faithful divine servant, as described in the epic of Lugalbanda, in which Anzû makes the clouds dense and roars at the rising sun; the creature blocks enemy forces at the command of Enlil. In Gudea Cylinder A, Anzû is still described as a divine emblem in close association with the god Ningirsu,who is a local form of the divine hero Ninurta in the city-state of Lagash. However, some time during the Ur III period, the role of Anzû changed, and the creature is suddenly counted among the slain enemies of the god Ninurta.”

Ur-Nanshe

Stele of Inanna (?)

Four-sided inscribed stele from Lagash (RIME 1.09.01.06a, P431039)

Now in the Iraq Museum (IM 61404): image from Wikimedia

Left: relief of goddess (Inanna ?)

Right: sketch of reliefs on all four sides by Claudia Suter (referenced below, Figure 1, at p. 346)

As noted above, one of these ‘populated’ reliefs is on the stele illustrated above: Claudia Suter (referenced below, at p. 345) pointed out that the relief:

“... shows [Ur-Nanshe] approaching an enthroned goddess, together with an entourage of sons and male officials, while a self-contained sub-scene below the king and his cupbearer [= his son Anita ?] depicts his [named] wife and daughter facing each other in banquet; the women share with the goddess her seated position, cup, and vegetal attribute, [which usually identified as a date palm].”

As we shall see, the identification of this goddess is important for our understanding of the religious sensibilities of the Lagash I kings.

In this context, it is interesting to note that:

✴the inscription under Ur-Nanshe; and

✴another on this side of the stele that runs horizontally under all four figures;

both read:

“Ur-Nanshe, son of Gunidu, ensi of Lagas, built the Ibgal [= oval temple of Inanna at Lagash].”

Unfortunately, the text under the goddess is now longer legible. Giovanni Lovisetto (referenced below, at pp. 54-5) observed that she:

“... holds a branch of dates and possibly a cup, while her extraordinarily long and voluminous hair falls from a (possibly horned) headdress over her shoulders. Her lower body is in profile, but her torso and head are shown frontally. Interestingly, the throne and her feet are placed on a sort of a podium, possibly signalling that this is a depiction of a statue, in front of which the five male figures are performing a libation ritual, perhaps during the inauguration of the Inanna temple itself. All the members of the royal family are labeled with their names and patronymics, but Ur-Nanshe is also described as ‘the leader of Lagash’ and as the builder of the Ibgal. Even though the name of the goddess is not preserved in the inscription, the reference to the Ibgal and the fact that the stele was found nearby have led most scholars to identify this figure as Inanna.”

Douglas Frayne (referenced below, 2008, at p. 87) observed that the worn figure of the goddess:

“... is strikingly similar in form to a goddess depicted on a large vessel with an inscription of [Ur-Nanshe’ great grandson], En-metena [RIME 1.9.5,25, discussed below, which is now in Berlin]. On the basis of its iconography, the figure on the Berlin piece can be confidently identified with the goddess Inanna. By extension, the goddess figure appearing on [the stele under discussion here] is almost certainly a representation of Inanna, [and the stele itself] probably came from the area of the Ibgal temple at Lagash.”

More recently, Francesco Pomponio (referenced below, at p. 6) agreed that this seated goddess is ‘probably Inanna;, It is possible that Ur-Nanshe used the title ‘ensi’ in this inscription (rather than ‘lugal’) in deference to Inanna.

References:

Rey S., “The Temple of Ningirsu: the Culture of the Sacred in Mesopotamia”, (2024) University Park, PA

Lecompte C., “A Propos de Deux Monuments Figurés du Début du 3e Millénaire : Observations sur la ‘Figure aux Plumes’ et l’a Prisoner Plaque’”, in:

Arkhipov A. et al. (editors), “Studies in Early Mesopotamia and Syria in Honor of Walter Sommerfeld and Manfred Krebernik”, (2020), Leiden and Boston, at pp. 417-46

Watanabe Ch. E., “Composite Animals in Mesopotamia as Cultural Symbols”, in:

di Paolo S. (editor), “Composite Artefacts in the Ancient Near East: Exhibiting an Imaginative Materiality, Showing a Genealogical Nature”, (2018) Oxford, at pp. 31-8

Wilson K. L., “Bismaya: Recovering the Lost City of Adab”, (2012) Chicago IL

Wazana N., “Anzu and Ziz: Great Mythical Birds in Ancient Near Eastern, Biblical, and Rabbinic Traditions”, Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society, 31:1 (2009) 111-35

Frayne D. R., “The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, Vol. 1: Presargonic Period (2700-2350 BC)”, (2008) Toronto

Øiseth A. R., “With Roots in the Abzu and Crown in the Sky: Temple Construction Between Myth and Reality: A Study of the Eninnu Temple of the Gudea Cylinders as Divine House and Cosmic Link”, (2007) thesis of the University of Oslo

Vanstiphout H. L. J., “Epics of Sumerian Kings: the Matter of Aratta”, (2004) Leiden and Boston

Wiggerman F., “Mesopotamian Protective Spirits: The Ritual Texts”, (1992) Gröningen

Pomponio F. “Did Ur-Nanše Defeat Ur?”, in:

Alivernini S. et al. (editors), “‘And I Have Also Devoted Myself to the Art of Music’: Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honor of Franco D’Agostino, Presented on His 65th Birthday by His Pupils, Colleagues and Friends”, (2025) Münster, at pp. 3-14

Goodman R., “A New Story of Sumer’s First Cities’, Expedition Magazine, 65:1 (2023) 30-3

Steinkeller P., “Urukagina’s Rise to Power”, in:

Cohen Y. et al. (editors), “Drought will Drive You Even Toward Your Foe”, (2023) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 3-36

Lovisetto G., “Goddesses Visualized in Early Dynastic Mesopotamia”, in:

Babcock S. and Tamur E. (editors), “She Who Wrote: Enheduanna and Women of Mesopotamia, ca. 3400–2000 BC”, (2022) New York, at pp. 46-63

Seminara S., “The World According to E-anatum: The Narrative of the Events in E-anatum's Royal inscriptions”, 24 (2020) 151-65

Westenholz A., “Was Kish the Center of a Territorial State in the Third Millennium? - and Other Thorny Questions”, in:

Arkhipov I. et al. (editors), “The Third Millennium: Studies in Early Mesopotamia and Syria in Honor of Walter Sommerfeld and Manfred Krebernik”, (2020) Leiden and Boston, at pp. 686-715

Rey S., “Girsu: Home of the Thunderbird”, Current World Archaeology (2019)

Steinkeller P., “Babylonian Priesthood during the Third Millennium BCE: Between Sacred and Profane”, Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions, 19 (2019) 112=51

Steinkeller P., “The Birth of Elam in History”, in:

Álvarez-Mon J. et al. (editors), “The Elamite World”, (2018) Oxford and New York, at pp. 177-202

Watanabe C. E., “Composite Animals in Mesopotamia as Cultural Symbols”, in”

di Paolo S. (editor), “Composite Artefacts in the Ancient Near East: Exhibiting an Imaginative Materiality, Showing a Genealogical Nature”, (2018) Oxford, at pp. 31-3

Desset F., “Here Ends the History of Elam: Toponomy, Linguistics and Cultural Identity in Susa and South-Western Iran (ca. 2400-1800 BC)”, Studia Mesopotamica, 4 (2017) 1-32

Suter C., “On Images, Visibility, and Agency of Early Mesopotamian Royal Women”, in:

Lluis F. et al. (editors), “The First Ninety Years: A Sumerian Celebration in Honor of Miguel Civil”, (2017) Boston and Berlin, at pp. 337-62

van Dijk-Coombes R. M., “Lions and Winged Things: A Proposed Reconstruction of the Object on the Right of the Lower Register of the Mythological Side of Eanatum's Stele of the Vultures”, Die Welt des Orients, 47:2 (2017) 198-215

Marchesi G., “Toward a Chronology of Early Dynastic Rulers in Mesopotamia”, in:

Sallaberger W. and Schrakamp I. (editors), “Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History and Philology: Vol. 3”, (2015) Turnhout, at pp. 139-58

Marchesi G., “The Inscriptions on Royal Statues (Chapter 4)”, in

Marchesi G. and Marchetti N. (editors), “Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia”, (2011) Winona Lake, IN, at pp. 155-86

Wang X., ”The Metamorphosis of Enlil in Early Mesopotamia”, (2011) Münster

Lapinkivi P., “The Sumerian Sacred Marriage and Its Aftermath in Later Sources”, in:

Nissinen M. and Uro R. (editors), “Sacred Marriages: The Divine-Human Sexual Metaphor from Sumer to Early Christianity”, (2008) University Park, PA, at pp. 7-42

Collins P., “The Sumerian Goddess Inanna (3400-2200 BC)”, Papers from the Institute of Archaeology, 5 (1994) 103-18

Winter I, J., “After the Battle Is Over: The ‘Stele of the Vultures’ and the Beginning of Historical Narrative in the Art of the Ancient Near East”, Studies in the History of Art, 16 (1985) 11-32

Cooper, J. S., “Reconstructing History from Ancient Inscriptions: The Lagash-Umma Border Conflict”, (1983), Malibu CA

de Sarzec E., “Découvertes en Chaldée: Second Volume Partie Epigraphique et Plances”, (1884)Paris