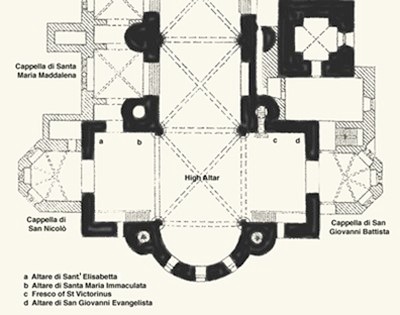

This diagram shows the positions of the altars that were originally on the (liturgical) west walls of the transepts of the Lower Church. The historical context is set out in the page on the San Francesco in the 14th century.

Right Transept

There seem to have been two altars on the right wall of the right transept:

-

✴the Altare di Sant’ Elisabetta (a), which was squeezed into the corner, under the fresco of the Crucifixion, to the left of the entrance to the Cappella di Santa Maria Maddalena; and

-

✴the Altare di Santa Maria Immacolata (b), under the fresco of the Maestà that is attributed to Cimabue.

Altare di Sant’ Elisabetta

Local tradition has it that Brother Elias established this altar soon after the canonisation of St Elizabeth of Hungary in 1235: the Emperor Frederick II, who presided over the translation of her relics at Marburg in 1236, wrote to Brother Elias at Assisi about the ceremony, stressing his kinship (through marriage) with St Elizabeth and recommending her to the prayers of the friars. The altar was first documented in 1360, when payment was recorded for a key for the metal grating that surrounded it. Fra Ludovico da Pietralunga (referenced below) recorded this chapel in ca. 1575, when it was still protected by the grating.

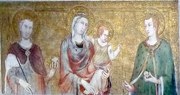

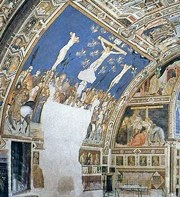

The only physical reminder of this altar are the frescoes (ca. 1317) in the right hand corner of the chapel, which are attributed to Simone Martini. These feature a number saints who were originally identified by inscriptions, but these are now illegible. Some of them seem to have belonged, like St Elizabeth, to the Árpád dynasty of Hungary:

-

✴The fresco on the right wall, which was originally over the altar, depicts the Madonna and Child flanked by two royal saints. The fact that they seem to be holding the orb and sceptre from the

royal regalia of Hungary, they are probably the great royal saints of Hungary:

-

•St Stephen, the first Árpád king; and

-

•St Ladislas.

-

✴The frieze on the back wall depicts five more saints:

-

•St Francis (far left);

-

•St Louis of Toulouse, who rests his renounced crown of Naples on the fictive frame around the fresco;

-

•St Elizabeth of Hungary, who points to the Madonna and Child on the right wall; and

-

•two saints with unfinished crowns above their respective haloes:

-

-a female saint who is often identified as St Clare, but (given the context) is more probably St Agnes of Bohemia or St Margaret of Hungary; and

-

-the male saint is probably St Henry (Emeric), the son of St Stephen, who embraced a life of celibacy (and hence carries a lily) and pre-deceased his father (signified by the unfinished crown above his halo).

As noted above, the identity of the fourth of these saints is uncertain. Her attributes are: the unfinished crown above her halo; her white veil, and the cross that she holds in her right hand:

-

✴Adrian Hoch (referenced below) identified her as St Agnes, the daughter of King Ottocar I of Bohemia (Přemyslid dynasty). If this is correct:

-

•the unfinished crown symbolises the fact that she renounced her royal birthright and founded the first nunnery of Poor Clares in Prague in 1234;

-

• the veil is one of the gifts that St Clare sent to her; and

-

•the cross records her devotion, typified by the fact that she invited the Order of Crosiers to Prague in 1252 so that they might run the hospital that she had established there.

-

St Agnes dies in 1283 and her cult was subsequently active at the court of her great nephew, King Wenceslas II of Bohemia. However, the process for her canonisation began only in 1328, when Elizabeth, the wife of King John of Bohemia and one of the last members of the Přemyslid dynasty, petitioned Pope John XXII. This process faltered, and St Agnes was not, in fact, canonised until 1989.

-

✴Gábor Klaniczay and Pierluigi Leone De Castris (referenced below) identified her as St Margaret, the daughter of King Béla IV of Hungary and niece of St Elizabeth. If this is correct:

-

•the unfinished crown symbolises the fact that her parents promised her to God if a threatened Tartar invasion was averted, and she duly became a Dominican nun, refusing all efforts to persuade her to marry;

-

•the veil is the relic that effected a miraculous cure of an illness suffered by her nephew, King Ladislas IV; and

-

•the cross symbolises her self-punishment: she died (in 1270) when only 28 years old from the effects of her asceticism and was later (from ca. 1340) depicted with the stigmata.

-

Her bother, King Stephen V began to press for her canonisation almost immediately after her death but the process faltered, and she was not, in fact, canonised until 1943.

Angevin Patronage

The presence of St Louis of Toulouse and a number of the saints of the Árpád dynasty suggest that the frescoes were commissioned by the Angevins of Naples: Queen Maria, who was the widow of King Charles II of Naples and the mother of St Louis, was also an Árpád princess and a great niece of St Elizabeth. She may well have commissioned the frescoes soon after the canonisation of St Louis in 1317. Her son, King Robert of Naples, who had benefited when St Louis renounced the crown of Naples and had been the prime mover in the campaign for his canonisation, could also have been associated with the commission. (The wider subject of Angevin patronage in San Francesco is described in the page on San Francesco in the 14th Century).

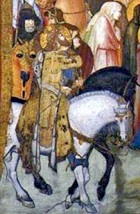

Another participant might have been Charles Robert, the grandson of Queen Maria. His father, Queen Maria’s oldest son, had died in 1295, when Charles Robert was only seven. Charles II therefore ignored his claim, and instead named his own second son, the future St Louis, as heir to the throne of Naples. He did however support Charles Robert’s claim to the throne of Hungary through his grandmother.

Charles Robert was sent to Hungary in 1300, at the age of twelve, and his chances increased when King Andrew III, the last member of the Hungarian Árpád dynasty on the paternal line, died in 1301. However, he faced stiff opposition, even after Pope Boniface VIII pronounced in his favour in 1303, and it was not until 1307 that he emerged as the only viable candidate. He could not, however, be crowned with the royal regalia because the rebellious Ladislas Kán, Voivode of Transylvania had stolen it and refused to hand it over. It was at this point that Queen Maria and the papal legate, Cardinal Gentile Partino da Montefiore arrived in Hungary to assist him. Cardinal Gentile excommunicated Ladislas Kán, and finally managed to secure his co-operation. Charles Robert was duly crowned with the royal regalia of Hungary in 1310. A number of factors suggest that Charles Robert might well have been associated with the commission of the frescoes:

-

✴he is known to have sent gifts to San Francesco with Cardinal Gentile, who arrived at Assisi in March 1312;

-

✴the frescoes underscored his status as the legitimate successor of the saintly Árpád kings of Hungary, with whose regalia he had recently been endowed; and

-

✴they also commemorated his uncle, St Louis, to whose cult he was devoted.

Brother John of England

Brother Ludovico da Pietralunga recorded that Brother John of England (died ca. 1247) was buried under this altar, and that a fresco depicting him was painted on the other side of the entrance to the Cappella di Santa Maria Maddalena. The surviving fresco seems to be later than the other frescoes around the two altars in this transept.

Altare di Santa Maria Immacolata

According to Brother Ludovico da Pietralunga, Pope Sixtus IV (1471-84) dedicated an altar here to the Virgin Immaculate, and this is entirely consistent with the known devotion of Sixtus IV to this theological doctrine. However, the fact that the altar was under Cimabue’s Maestà (ca. 1275) suggests that there had been a Marian altar here from an early date. The painted wooden statue (1588-9) of the Immaculate Virgin, which was commissioned for this altar, was removed in 1860 and is now in the Cappella di Sant’ Andrea.

Brother Ludovico also records that five of the

early followers of St Francis who were buried behind the grating here were depicted in half-length figures and identified in

a now-lost painted inscription as:

-

✴Brother Bernard of Quintavalle (died after 1241);

-

✴Brother Sylvester (died ca. 1240);

-

✴Brother William of England (died 1232);

-

✴Brother Electus (died 1253); and

-

✴Brother Valentine of Narni.

In fact, the last of these could not be correct because the Blesses Valentine of Narni died in 1378, some decades after it the fresco been painted. In any case, it seems more likely that he was buried in the nearby Cappella di San Valentino.

The inscriptions apparently provided more information on two of these early friars:

-

✴When miracles occurred at the tomb of Brother William of England, Brother Elias asked him to desist out of reverence for St Francis.

-

✴Brother Electus apparently predicted that Cardinal Pierre de Colmieu “will die here, today”. The Chronicle of the XXIV Generals (1375) recorded that the cardinal did indeed die in the Sacro Convento, when a beam fell on him after its consecration in 1253 (paragraph 252). (Franciscan sources denounced the slander that this had happened because he detested their order). Brother Electus presumably died shortly thereafter.

The lost inscription presumably corresponded to the inscriptions (no longer legible) in the fresco (ca. 1320) above the grill, which depicts five friars gazing up at the fresco of the Maestà. This fresco is attributed to a follower of Pietro Lorenzetti.

Left Transept

There may also have been two altars on the left wall of the left transept:

-

✴The fresco of St Victorinus (c) to the right of the door to the sacristy may have been part of a fictive altarpiece, although there is no record of any corresponding altar. Alternatively, it may have simply formed part of a frieze of images of saints, like that on the back wall (see the illustration above).

-

✴The Altare di San Giovanni Evangelista (d) formed part of a fictive chapel that was squeezed into the corner, to the right of it.

The arrangement on this wall was modified when another altar, the Altare delle Reliquie, was installed in 1607. It was removed in ca. 1870, leaving a large area of damage.

Fresco of St Victorinus

As noted above, the fresco of St Victorinus (identified by inscription) to the right of the door to the campanile might originally have formed part of a frescoed altarpiece. If this is correct, then the Altare delle Reliquie must have replaced an earlier altar with a different dedication.

According to Brother Ludovico da Pietralunga, four the early followers of St Francis were buried behind a grate on the left wall of the left transept. An inscription identified them as:

-

✴Brother Leo (died ca. 1275);

-

✴Brother Masseo (died ca. 1280);

-

✴Brother Rufino (died ca. 1278); and

-

✴Brother Angelo (died 1258).

Frescoes depicting the deceased were destroyed when Altare delle Reliquie (see below) was installed. and the tomb itself seems to have been destroyed when this altar was removed in ca. 1870. The remains of these friars were moved to the crypt in 1934.

Altare di San Giovanni Evangelista

An altar in the left transept dedicated to St John the Evangelist was first documented in 1300. The only physical reminder of this altar are the frescoes (ca. 1315) in the left corner of the right transept which are attributed to Pietro Lorenzetti.

-

✴The fresco on the left wall, which was originally over the altar, depicts the Madonna and Child with SS Francis and John the Evangelist (see below). It is known as the “

Madonna dei Tramonti” (Our Lady of the Sunsets) because it catches the light of the evening sun. The frieze that acts as its fictive predella depicts:

-

•a crucifix at the centre flanked by two sets of arms depicting a golden lion; and

-

•a lost figure on the extreme left who was commended to the Madonna and Child by St Francis, with a pendant figure on the extreme right.

-

✴The fresco on the back wall depicts four more saints (identified by inscription) above a

trompe l' oeil bench:

-

•St Nicholas of Bari;

-

•St Catherine of Alexandria;

-

•St Clare; and

-

•St Thecla.

-

✴The frescoed niche in the corner, to the right of the fictive predella, which is now very damaged, depicts liturgical objects, including two flasks for wine.

At the time that Brother Ludovico described the fictive altarpiece, there were apparently no donor portraits in the predella: he describes the Crucifix and four coats of arms, each of which depicted a rampant lion. He identified these arms somewhat vaguely as those of the Duke of Athens, whom he believed was depicted in the fresco of the Crucifixion above, (the bearded man riding a mule on the extreme left). The two surviving coats of arms are now illegible and the apparent overpainting of at least one of the other two is unexplained.

Giorgio Vasari identified the arms more specifically as those of Walter VI of Brienne (which are depicted in the page on him in Wikipedia). Walter VI and his mother had lived under Angevin protection since 1311, when his father had died in a vain attempt to prevent the Catalan invasion of his duchy. Walter VI retained the nominal title of Duke of Athens and married a niece of King Robert of Naples in 1325. King Robert installed him as governor of Florence in 1342, although his unpopular régime was destined to last for only a matter of months. Vasari was reluctant to accept the tradition that he had commissioned the altarpiece, probably because he had been only a teenager when it was painted. It is, of course, possible that his mother, Joanna of Châtillon (still titular Duchess of Athens) commissioned it on his behalf: in that case, the bearded figure in the Crucifixion could not have been Walter VI, but it could have represented his dead father.

Altare delle Reliquie

As noted above, the Altare di San Giovanni Evangelista was conceded to Camilla Peretti, the sister of Sixtus V, in 1604. In 1607, Cardinal Alessandro Peretti di Montalto (the son of another sister of Sixtus V) installed the Altare delle Reliquie next to it, in order to house the venerated Sacro Velo della Madonna (Sacred Veil of the Virgin) and other relics possessed by the friars. This resulted in the destruction of the lower part of the fresco of the Crucifixion (and possibly an altar below it).

The body of Princess Maria of Savoy was interred here in 1662. She was the daughter of Duke Charles Emmanuel I of savoy and Catherine, the daughter of King Philip II of Spain and became a Franciscan tertiary in Rome. She died there in 1656 and, because this occurred during an outbreak of plague, her wish to be buried in San Francesco, Assisi had to be deferred. Pope Alexander VII sent a stone inscription for her new tomb from Rome in 1663.

As noted above, the Altare delle Reliquie was removed in ca. 1870.