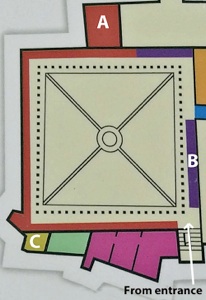

Three rooms off the Upper Cloister contain interesting exhibits:

-

✴A: Bronzes from San Mariano.

-

✴B: Urns from the Tomba dei Cacni.

-

✴C: Coin Hoards from Bevagna and Gualdo Tadino.

A: Bronzes from San Mariano

In 1812, a peasant accidentally discovered a spectacular cache of objects in what seems to have been a princely chamber tomb at Castel di San Mariano di Corciano, 10 km south west of Perugia. The discovery 200 years later of a relevant document in the archives of Perugia has finally allowed scholars to identify the precise location. Some 275 objects seem to have been found here, of which 180 are still in the museum.

The rest of the material was widely dispersed. For example:

-

✴King Ludwig I of Bavaria bought three of them from the English antiquarian, Edward Dodwell, and these passed to in the Staatlichen Antikensammlungen, Munich.

-

✴Some 70 other objects that passed through the hands of Edward Dodwell are now in the Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Monaco.

-

✴Three fragments of a silver repoussé relief (ca. 530 BC) from this tomb, which are now in the British Museum, London, may have come from a chariot of3from a piece of furniture. They depict:

-

•two men in a chariot and another fallen soldier (illustrated here);

-

•a lion; and

-

•a fragment with two scenes:

-

-part of a boar being attacked by a lion; and

-

-a sphinx.

A summary of the contents of the 15 display cases in this room is given in the webpage Bronzes for San Mariano. The whole collection of Etruscan bronzes found in 1812 has been published as a series of data tables in M. Cipollone, “I Bronzi da Castel San Mariano: Lo State delle Cose”, Bollettino di Archeologia On Line, 2:2-3 (2011) 20-43.

Reliefs from a Two- Wheeled Chariot (ca. 560 BC)

Reliefs in Case 1 Illustration of a relief in Monaco

A number of the reliefs from the sides of this chariot are displayed in Case 1. The striking relief illustrated above on the right, which came from the back of the chariot, is now in Monaco: the image above is from the explanatory panel in the museum describing this chariot:iti is also illustrated in Mafalda Cipollone (referenced above, at p. 28) as 12 WAF 720r. It depicts a squatting gorgon who grasps what was probably originally a pair of lions by their throats.

Reliefs from a Two- Wheeled Chariot (ca. 525 BC)

The fragments from this chariot, which are displayed in Case 2, belonged to a relief depicting scenes from the battle between Zeus (Etruscan Tinia) and the giants:

-

✴on the left, he holds a thunderbolt and seizes a giant by the hair; and

-

✴on the left, he welcomes his ally Hercules (Etruscan Hercle) to Olympus.

These fragment are illustrated in Mafalda Cipollone (referenced above, at p. 29) as 40 CSM 141 and 41 CSM 142.

Other Remains fromThis Chariot

These remains from the chariot above are displayed in Case 3.

Reliefs, possibly from a Chariot (ca. 525 BC)

Fragment illustrated in Mafalda Cipollone (referenced above, at p. 29) as 55 CSM 147 and

drawing from the explanatory panel in the museum

Fragment illustrated in Mafalda Cipollone (referenced above, at p. 30) as 57 CSM 146 and

drawing from the explanatory panel in the museum, with my text added

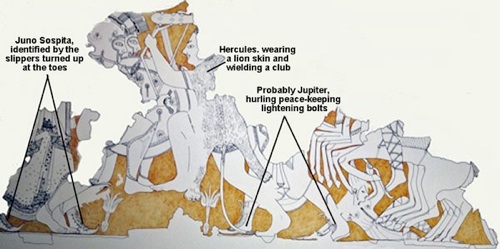

The fragmentary reliefs in Case 4 come from the parapet of what was probably a third chariot. Mafalda Cipollone (referenced above, at p. 24) designated this vehicle as ‘Streitwagen II’, and identified the scene as:

-

“... probably ... the episode of Hercules and the Amazons”, (my translation).

This scene would have involved the ninth labour of Hercules, in which he stole the belt of Hippolyte, Queen of the Amazons, after a battle in which Hera (Roman Juno) incited the Amazons to resist and Hippolyte was killed. In relation to fragment 57 CSM 146, Erika Simon (referenced below. at p. 51 and figure IV:11, p. 54) identified:

-

✴the feet of the figure on the extreme left as those of Juno Sospita (whose iconography involved slippers turned up at the toes - see below);

-

✴the figure wielding the club visible at the top right as Hercules, wearing his lion skin; and

-

✴the fragmentary figure behind him (whose feet also survive) as Jupiter (Etruscan Tinia), who probably hurled:

-

“... the peace-making lightening bolt, ... [so that Juno Sospita] and Hercules will be reconciled by the will of [Jupiter].”

Juno Sospita

In the text above, I have used the Latin name Juno Sospita (probably Juno the Saviour), for the goddess on the left, who wears distinctive slippers with upturned toes. However, this identification relies heavily on a single passage from a work that Cicero wrote in 45-4 BC: in it, he recorded that a goddess with that name, who was closely associated with the Latin town of Lanuvium (see below), was characterised by four iconographic attributes:

-

“... her goat-skin, spear, shield and slippers turned up at the toe”, (‘On the Nature of the Gods’, 82)

The Putative Juno Sospita in Etruria

The surviving fragment of the goddess in 57 CSM 146 reveals only her distinctive footwear, but the probable context of the scene allows us to assume that:

-

✴she was armed with a shield and spear; and

-

✴she wore a goat-skin that matched Hercules’ lion-skin.

This assumption is supported by the fact that 57 CSM 146 was not an isolated Etruscan example of the iconography recorded by Cicero: indeed, Rianne Hermans (referenced below, at p. 113) pointed out that the earliest surviving examples of this iconography:

-

“... were mostly found in an Etruscan context and show the goddess in a characteristic military pose. To begin with, there are a number of interesting images in which [this putative] Juno Sospita is accompanied by Hercules, [she] wearing her goat-skin just as Hercules wears his lion-skin.”

Hermans described a few examples, including:

-

✴a pair of reliefs from two sides of the base of a tripod (520-500 BC) from Castel San Mariano (now in the Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich; illustrated as 126 WAF 720g in Mafalda Cipollone, referenced above, at p. 32):

-

•one depicting Uni facing right; and

-

•the other Hercle facing left; and

-

✴an Etruscan amphora (530-520 BC) attributed to the so-called Paris Painter that probably came from Cerveteri, (now in the British Museum), which depicts a stand-off between:

-

•Hercle (restrained by Menerva); and

-

•Uni (restrained by Tinia)

In both of these examples, Uni appears with all four of the attributes in Cicero’s list, and in an aggressive posture in relation to Heracle (who wears his lion-skin). Hermans (as above) noted that this composition:

-

“... seems to be a local phenomenon from Etruria, and none of the images [of this kind] can be connected to Lanuvium or, for that matter, to Latium.”

Juno Sospita at Lanuvium

The surviving evidence for the the cult of Juno Sospita at Lanuvium goes back to the Romans’ definitive victory over the Latins in 338 BC, following which, according to Livy:

-

“The people of Lanuvium were given civitas [citizenship, probably with voting rights] and their cults were restored to them, with the stipulation that the temple and grove of Juno Sospita should be held in common by the citizens of Lanuvium and the Roman people”, (‘History of Rome’, 8: 14: 2-3).

Most scholars assume that the goddess in 57 CSM 146 (and in other early Etruscan images) was equivalent to Juno Sospita, the supreme goddess of Lanuvium. However, although we can trace:

-

✴her distinct iconography (as Cicero recorded it in 44-5 BC) back to Etruria in the 6th century BC; and

-

✴her temple and grove at Lanuvium back to 338 BC (when the Romans effectively took control of it);

it is important to remember that we do not know:

-

✴whether or not the Etruscans had a specific name for this manifestation of the goddess whom they called Uni; or

-

✴when the distinct iconography described by Cicero first appeared in the context of her cult at Lanuvium, albeit that it was well-established there by 45 BC.

B: Urns from the Tomba dei Cacni

An Etruscan hypogeum was discovered in 2003 in the district of Elce, immediately to the northwest of the Etruscan city, between the Arco Etrusco and Porta Trasimena. Unfortunately, it was robbed and destroyed soon after, and the stolen material was not recovered until 2013.

Associated grave goods are also displayed here, from the periods from the 4th to the 1st century BC.

C: Coins from Bevagna and Gualdo Tadino

Bevagna

Coin Hoards (211 - 115/ 110 BC)

Original exhibit Coins as now exhibited

Hoard from Viale Properzio/ Via I Maggio

This hoard of 234 coins, which included dateable coins from the period 211-110 BC, was discovered in 1980 during the excavation of the cult site between Viale Properzio and Via I Maggio. The coins were in a terracotta jar (also illustrated) that had probably been placed inside a wooden container and buried in a cavity some 800 cm below the ground. There is no evidence that the coins had been accumulated over a long period: the older coins are badly worn, and could well have been in circulation alongside the later ones. Thus, this seems to have been a case in which a number of coins were interred for safety, perhaps by the officials who administered the cult.

The museum used to exhibit these coins and their container in the Sala dei Bronzi (as illustrated above, on the left). As currently exhibited, some coins remain in the original container and another 30 are exhibited separately.

Hoard from Outside Porta Foligno

A hoard of 911 coins, which included dateable coins from the period 211-115 BC, was found outside Porta Foligno, Bevagna in 1929. Part of this hoard is in the deposit of the museum [check]: unfortunately, the other part, which was originally exhibited locally, was later stolen.

Gualdo Tadino

This room also displays 99 silver coins that were found in a terracotta vase (now lost) in 1951 at Grello, some 8 km southwest of Gualdo Tadino. All the coins had been minted at Rome, and those that could be dated belong to the period between the short reign of the Emperor Otho (69 AD) to the reign of Commodus: the three coins from the latter reign date to 184 AD.

Read more:

E. Simon, “Gods in Harmony: the Etruscan Pantheon”, in:

N. Thomson de Grummond and E. Simon (Eds), “The Religion of the Etruscans”, (2006) Austin TX, at pp. 45-65

Return to the page on upper level of the large cloister

Return to the main page on the Museo Archeologico