The Museo Archeologico is in the ex -Collegio Boccarini. It is well arranged, and the extensive explanatory panels (with English translations) fill in the gaps that are inevitable in a small town like Amelia that has suffered the dispersal of its most important archaeological remains. At least the statue of Germanicus (see below), which was for many years in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Perugia, has now been returned to form the highlight of the collection.

The ground floor houses pre-Roman exhibits while the 1st and 2nd floors represent the Roman municipium of Ameria.

Ground Floor

Grotta Bella

A photographic exhibition depicts the so-called Grotta Bella on Monte Aiola, Avigliano Umbro, north of Amelia, which was inhabited from the 12th century BC. It was discovered in 1902 and excavated by the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici dell'Umbria in 1970-2. Bronze Age finds from the site are exhibited in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Perugia.

Votive objects found during the excavations provide evidence for the cult use of the site from the 7th until the 1st century BC. The prevalence of votive offerings and coins from the 3rd century BC suggest that this was the period of greatest cult use. The site was probably abandoned after the Social Wars (90-89 BC).

Amelia in the Iron Age (9th - 8th century BC)

Excavations carried out in 1993 in the cellars of Palazzo Boccarini unearthed a large number of ancient fragments in the fill material. The material was heterogenous and removed from its original location. It nevertheless pointed to the habitation of the locality from at least the late Bronze Age and to a flourishing culture in the Iron Age that was in contact with other settlements in the Tiber Valley.

Necropolis and Temple at Pantanelli (6th - 2nd centuries BC)

A necropolis at Pantanelli (southeast of Amelia) was excavated at the end of the 19th century. The type of tombs from the earliest period and the existence of imported ceramic fragments among the grave goods suggested the existence of a ruling élite in the region at that time, and pointed to its extensive interaction with both the nearby Etruscan city of Volsinii (Orvieto) and the Etruscan-influenced Umbrian community at Todi.

An associated sanctuary was also found during the excavation of the necropolis. Unfortunately, the lovely bronze of figure of Demeter in a chariot that was found here is now in the British Museum, and many of the other bronze votive statues from the temple now belong to the Museo Nazionale Etrusco, Villa Giulia. Fragments of other votive offerings (6th - 4th centuries BC), including the clay model of a foot illustrated above, are displayed in the museum at Amelia.

Fragments of terracotta antefixes (4th or 3rd century BC) found nearby suggests that the ancient sanctuary was subsequently monumentalised.

Necropolis outside Amelia (4th century BC - 2nd century AD)

The Consorzio Agrario (agricultural co-operative) of Amelia stood on Via delle Rimembranze, near the place at which the fragments of a statue of Germanicus (see below) and other Roman remains were found in 1963. When the Consorzio was demolished in 2001, the remains of a necropolis were discovered. The earliest burials here dated to the 7th century BC, but no graves from the 6th and 5th centuries BC were discovered. The necropolis was formalised in the 4th century BC, at which point the simple tombs were laid out on shallow steps. Most of the tombs had been violated, but the remaining grave goods were nevertheless of high quality.

The grave goods also include Faliscan red-figure pottery (ca. 330 BC). The examples illustrated here are:

-

✴a patera (a shallow dish used for drinking, usually in a ritual context) decorated on both surfaces with designs featuring satyrs;

-

✴an oinochoe (wine jug) decorated with a satyr holding a drum before an unidentified seated figure;

-

✴a fragment of a cratere (vase) with a design featuring a dancing satyr and maenad, which is attributed to the so-called Fluid Group of vase painters.

Female grave goods include jewellery (much of it gold), ceramic perfume bottles and a number of bronze objects, including mirrors. The mirror illustrated here, which has a bone handle, probably dates to the 4th century BC.

Other grave goods from the necropolis, all of which date to the 4th or 3rd century BC, are now exhibited now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Perugia.

Temple at Santa Maria in Canale (3rd - 2nd centuries BC)

The museum has photographs of the remains of the temple that are now incorporated into a farmhouse known as the Podere di Santa Maria in Canale (near Sambucetole, some 6 km north of Amelia). This was the site of the Monastero di Santa Maria da Canale, which was closed in 1428.

An ancient cult site here was subsequently monumentalised, probably in ca. 200 BC. The podium of the resulting structure survives below ground level, and part of a wall built of travertine blocks provides the foundations of a wall of the present structure. The temple had a central space flanked by two smaller rooms, and a pronaus with two rows of four columns.

Votive inscription (late 4th century BC)

These five-line inscriptions, which use an Etruscan alphabet from Volsinii (Orvieto), are similar but not identical, and their fragmentary nature makes them difficult to understand. The first line of each seems to record the dedication of a gift (“dunu”) to a deity (“duvie”), perhaps Jove or another deity associated with him. The other lines probably record the family names of the donors.

The inscription is placed in its wider context in the page on Umbrian Inscriptions before the Roman Conquest.

First Floor

Neo-attic Altar (1st century BC)

Boundary Marker (1st century BC)

Inscriptions Relating to the Gens Roscia

The Roscius family of Ameria is well known because Cicero successfully defended Sextus Roscius from a charge of patricide in 80 BC, and subsequently published his speech for the defence, “Pro Roscio Amerino”. This provides a fascinating insight into the political terror of the time, as Sulla proscribed his enemies and confiscated their property.

Cicero tells us that the deceased was “by far the first man not only of his municipality, but also of his neighbourhood, in birth, and nobility and wealth”. He argued that this man had been unfairly proscribed so that his property could be stolen by two relatives, Titus Roscius Magnus and Titus Roscius Capito, and that his murder and the charge against his son were part of the plot. The younger Sextus Roscius was duly acquitted, although nothing further is known about him. An inscription (1700) above the portal in the courtyard of Palazzo Piacenti (see the Walk around Amelia) records that Antonio Piacenti restored the palace, which stood on the site of part of the confiscated property of the Roscia family.

Funerary Urn (1st century BC)

GLAPHYRUS ROSCIAE

VILICUS

CINNAMINI CONSERVAE

It records that Glaphyrus, the steward of a female member of the Roscia family, had commissioned the urn for a fellow-servant, Cinnamis.

This inscription was recorded in a sketch (1564) by the sculptor and antiquarian Giovanni Antonio Dosio that survives in the Staatsbibliothek, Berlin. It was then in a rural church south west of Amelia, which was probably close to the farm of the Roscia family that Glaphyrus managed.

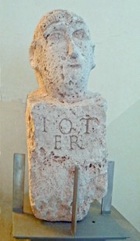

Inscribed Thesaurum (1st century AD)

T ROSCIVS T F AVTVMA

IIII VIR ITER

P LXXV

This records that Titus Roscius Autuma, son of Titus, who was a quattuorovir for the second time, provided a thesaurum (a container used in a temple to receive offerings) at his own expense. The weight, 75 Roman pounds (about 25 kg) cannot refer to the trough itself; it probably refers to a lost component, perhaps a bronze lining that acted as a safe. The trough would originally have had a lid, but this was presumably lost when it was adapted (probably in the 16th century) to serve as a fountain.

Titus was obviously a member of the gens Roscia, which was well known in and around Amelia. He might well have been a descendant of Titus Roscius Magnus and/or Titus Roscius Capito. The (probably Etruscan) cognomen "Autuma" is otherwise unknown.

Finds from Località Cinquefonti

The area to the southwest of Amelia, between the churches of San Secondo and Santa Maria delle Cinque Fonti (of the five springs) is named for a drinking trough built over a Roman structure, traces of which can be seen in a house in the area (see the Walk around Amelia).

A large number of Latin inscriptions have been found in this area. These include the so-called Feriale Amerinum (CIL XI 4346; ca. 50 BC), which is found in 1889. It lists the festivals of the deities that were celebrated locally: Victoria Caesaris; Felicitas; Fortuna Vesta; Jove Optimus Maximus; Apollo; Fortuna and Mercury. Each name was originally preceded by the date of the relevant festival, and each was followed by the abbreviation

h[ostiae] (victim or sacrifice). These were presumably followed by brief details of the number of animals to be sacrificed on each occasion. The inscription is now privately owned.

A number of finds discovered here in 1965 suggest that it was the site of a Roman necropolis. These included the following:

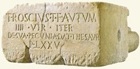

Funerary Urn (1st century BC)

The inscription along the top of this funerary urn reads:

T[itus] GNEUIDIUS T[iti] L[ibertus] SECUNDUS FEC[it]

SUCONIAE C[aiae] L[ibertae] NICE MATRI SUAE

This records that Secundus, a freedman who had belonged to the Gens Gneuidia, had commissioned the urn for his mother, Nice, a freedwoman who had belonged to the Gens Suconia.

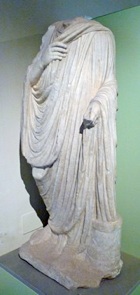

Man in a Toga (1st century BC)

Finds from the Roman Theatre (1st century BC)

The area close to the church of Sant' Elisabetta (also called Santa Lucia - see the Walk around Amelia) seems to have been the site of the Roman theatre, which was apparently embedded in the hillside. This semi-circular structure seems to have had a diameter of some 70 meters. A number of capitals and fragments of columns and cornices were discovered when the area was excavated in 1839-40, some of which survive in the atrium of Palazzo Comunale.

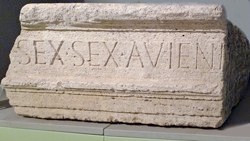

Inscriptions

This inscribed architrave (CIL XI 4383), which was unearthed during the excavations of 1839-40 records “Sex[tus] Sex[tus] Aveini[...]”, presumably two brothers from the gens Aviena who had at least partially financed the theatre.

Another inscribed architrave (CIL XI 7837), which was unearthed in 1914, records another “Sex[tus] Avie[...]”, who was probably the son of one of the brothers above. This inscription was not displayed at May 2011.

Sculpture

These two fragments were among the objects excavated in 1839-40. They come from statues of:

-

✴a figure in a toga; and

-

✴a figure of a military officer.

Finds from the Roman Baths

Palazzo Farrattini was built on the site of the Roman baths of Ameria. Most of the surviving structure was destroyed when the palace was built in the 16th century, although two black and white mosaic floors (2nd century AD) survive inside, some 4 meters below the present pavement level. These rooms are connected to the subterranean cistern that is now on the opposite side of the road.

Man in a Toga (1st century BC)

This small statue, which was apparently found near the palace, probably came from a niche in the baths. If this is correct, they were clearly used over a considerable period of time.

Bust of Livia (1st century AD)

This marble bust was documented in ca. 1870 embedded in a wall near Palazzo Farrattini. It almost certainly represents Livia, the wife of the Emperor Augustus.

Finds from Via delle Rimembranze

A number of important discoveries were made in 1963 in Via delle Rimembranze, outside Porta Romana, on what was probably an army parade ground (see the Walk around Amelia).

Statue of Germanicus (ca. 40 AD)

The most important of these finds were the pieces of this remarkable bronze statue. The base found nearby was not inscribed, but the statue is generally accepted as a portrait of Germanicus. He was the adopted son of the Emperor Augustus, a fine soldier who was awarded honours after leading theRoman army in what is now Germany in 9 AD. He died in Syria in 18AD. The statue probably dates to:

-

✴the reign of the Emperor Tiberius (14-37 AD), the stepson of Augustus and Germanicus’ adoptive father, who is sometimes accused of his murder; or

-

✴that of the Emperor Caligula (37-41 AD), Germanicus’ son.

After the skilful reassembly of the bronze fragments on a steel frame, Germanicus now stands some two metres high. He is dressed in full armour exhorting the troops. His breastplate is decorated with a relief in which Achilles attacks Troilus, the youngest son of King Priam, outside the walls of Troy. (Legend has it that Achilles dragged the handsome Troilus from his horse by his hair, intent upon raping him. Troilus escaped and took refuge in a temple, but Achilles beheaded him there and mutilated his body).

Capital (early 1st century AD)

Funerary Altar (1st century AD)

This funerary altar, which is beautifully carved on three sides, has a fragmentary inscription that probably originally identified the deceased and the person who had commissioned the altar for him. The relief on the front, above a garland, probably depicts the birth of Dionysus.

Funerary Altar (1st century AD)

The altar was first documented in the Duomo in a sketch (1564) by the sculptor and antiquarian Giovanni Antonio Dosio that survives in the Staatsbibliothek, Berlin.

Read more:

M. Chiari and S. Stopponi (Eds), “Museo Comunale di Amelia: Raccolta Archeologica: Iscrizioni, Sculture, Elementi Architettonici e d' Arredo”, (1996) Perugia

M. Chiari and S. Stopponi (Eds), “Museo Comunale di Amelia: Raccolta Archeologica: Cultura materiale”, (1996) Perugia

For opening hours, see this page in the website of the Commune.

Return to Museums of Amelia.

Return to the Walk around Amelia.