Bettona

Inscribed cippi (late 3rd or early 2nd century BC)

These two sandstone cippi seem to have come from a necropolis outside Bettona. They bear Etruscan inscriptions (respectively PE 8.2 and 8.3):

-

✴“tular larna”; and

-

✴“tular larns”.

The word “tular” probably meant boundary and the cippi seem to have marked the boundary of the area in which the “larna” family buried their dead. This name is known from inscriptions from the necropolises of Volsinii (Orvieto), and it could be that the family left Volsinii when it was destroyed in 264 BC. The cippi are now in the Museo Civico, Bettona.

The museum also exhibits three funerary cippi from the city on which the Etruscan names of the deceased were inscribed:

-

✴“au casne nav[.....]” (PE 1.682)

-

✴“[.....]rmial” (PE 1.683); and

-

✴“larθia caia au sec” (PE 1.685).

Perugia

Ipogeo di San Manno (late 3rd century)

An important 3-line inscription has been uncovered above the entrance to the left cell of the Ipogeo di San Manno, outside Perugia:

cehen óuθi hinθiu θues óians etve θaure lautnescle careóri

aules larθial precuθurasi larθialióvle cestnal

clenarasi eθ fanu lautn precus ipa murzua cerurum ein heczri tunur clutiva zelur

This reveals that the tomb belonged to the brothers Avle and Larth Precu, the sons of Larth and his wife, a lady from the Cestna family. The last part of the inscription seems to prescribe the way that the tomb is to be used.

Cippus of Perugia (ca. 200 BC)

This travertine boundary stone was found in 1822 on Colle San Marco, outside Perugia. The rough finish of the lower part suggests that it was originally partly buried in the ground. The inscription, which comprises 24 lines on the front and another 22 on the left side, is one of the longest Etruscan texts in existence.

The inscription, which comprises 24 lines on the front and another 22 on the left side, is one of the longest Etruscan texts in existence. The traditional translation suggests that the inscription documents a legal contract between the two families of the Velthina (already known in Perugia) and the Afuna (from the Chiusi area) and relates to a property upon which there was a tomb belonging to the former. It contains the word “rasnes”, which refers to the Etruscan people as a whole, in a context that probably records that the agreement is made under Etruscan law. A judge named Larth Reza witnessed it, and it ends with an official formula “zichuche” (it is written).

The cippus is now in the Museo Archeologico, Perugia. There is more detail about it on the site of the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici dell'Umbria. The full inscription (CIE 4538) and a possible translation into Italian is given in this page by Professor Massimo Pittau. The importance of this inscription in the understanding of Etruscan is described in the page on Early Etruscan Inscriptions).

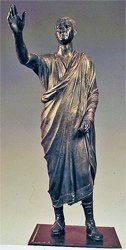

Arringatore (ca. 100 BC)

This bronze statue known as the Arringatore (Orator), which was found in 1563, (probably) at Pila di Perugia. The Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici claimed it for Florence in 1566, and it is now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Florence. It was cast in seven pieces by the lost-wax process. The figure wears a Roman toga and adopts the stance of a Roman orator.

The inscription along the hem of the toga is in Etruscan despite the very Roman character of the figure. It has been transcribed as:

aulesi metelis ve vesial clensi

cen fleres tece sansl tenine tuthines chisvlics

This (probably) translates as: “To (or from) Aule Meteli, son of Vel and Vesi: this statue was erected as a votive offering to Tec Sans by deliberation of the people”. The figure certainly does not represent Tec Sans, a local deity dedicated to the protection of children: it probably portrays Aule Meteli himself.

The statue is also described on the page that deals with finds from Pila in the Museo Archeologico, Perugia.

Publius Volumnius Violens (ca. 9 BC)

This urn in the

Ipogeo dei Volumni, outside Perugia (see above), is made from Luna marble, which was only mined in significant quantities after ca. 40 BC. It takes the form of a Roman temple, and seems to have been inspired by the much larger and grander

Ara Pacis (altar of peace) in Rome, which was dedicated in 9BC. The urn was probably made in Rome at about this time, and it would have been in the most “modern” style of its day.

Despite the very Roman character of the urn, it has a bilingual funerary inscription:

-

✴The Latin inscription on the lintel of the door to the fictive temple, which identifies the deceased as:

-

P[UBLIUS] VOLUMNIUS A[ULI] F[ILIUS] VIOLENS

-

CAFATIA NATUS

-

The Latin "Cafatia natus" reveals that the mother of Publius Volumnis was called Cafatia. He was obviously very “Romanised”, but he followed the Etruscan tradition of identifying his mother (as well as his father, Aule) in his own name. He had adopted a Roman cognomen, Violens, that was presumably meant to imply descent from Lucius Volumnius Flamma Violens, who was the first plebian to become Consul in Rome, in 307 BC.

-

✴The Etruscan inscription, which also uses the Etruscan alphabet, appears on the lid of his urn:

pup[li] velimna au[le] cahatial

-

"Cahatial" must have had the same meaning in Etruscan as the Latin "Cafatia natus".