Province of Tuscia et Umbria (ca. 294 AD)

As set out in my page on History: 4th Century AD: Tuscia et Umbria, the Emperor Diocletian seems to have created administrative provinces in Italy for the first time in ca. 294 AD. Among these Italian eight provinces was the Province of Tuscia et Umbria, which presumably absorbed the cities of what had been:

-

✴the Augustan region of Etruria; and

-

✴the part of Augustan region of Umbria that lay to the west of the Apennines.

The epigraphic record includes a series of governors of this province in the period from ca. 310 AD until some time after 366 AD (when the title apparently changed from Correctore or Consulare).

It is sometimes asserted that Volsinii was the capital of Tuscia et Umbria, which might (it is argued) explain why, at the time of the Rescript of Constantine of ca. 335 AD (see below), joint Etruscan and Umbrian games were held here. However, as Enrico Zuddas (referenced below, at pp. 228-9 and note 50) observed, there is no other evidence for this hypothesis, and the content of the Rescript alone is insufficient to support it.

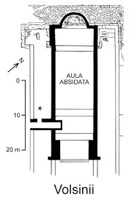

Basilica Forense (early 4th century AD)

Excavated area of the northern end of the Flavian forum

The remains of the apse of the basilica forense can be seen to the right, encroaching on the road behind it

Aerial view of the excavated Plan of modified basilica forense

basilica forense and its apse, With the kind permission of

with its ‘new’ side walls picked out dott. Pietro Tamburini

As noted in the previous page, the Flavian basilica forense, which had probably had a civic function, was probably damaged by the fire of 270 AD that destroyed other nearby buildings. According to Pierre Gros (referenced below, 1981, at p. 49):

-

“At the beginning of the 4th century AD, this civic basilica was transformed into a Christian church. This involved the construction of an apse on the axis of the nave, without any concern for the fact that this encroached on the decumanus [that previously bordered the basilica - see the illustrations above], making [this road] difficult to use. The construction of its walls in opus vittatum mixtum ... is comparable to that of the staircase excavated in the [left] side of the basilica in order to provide access from the lower terrace. It is likely that this Christian church used only part of the ancient pagan building (as frequently happened): the [late 4th century tombs], which were huddled at the stylobate of the nave, attest to the fact that the [side aisles ??], already in ruins, no longer belonged to the covered building ...” (my translation).

(The remains of this basilica survive in what is now an archeological area here, that can be visited).

-

✴According to Annarena Ambrogi and Ida Caruso (referenced below, 2012 and 2013), the original bust of Octavian was of the so-called Béziers-Spoleto type (ca. 40 BC), and probably came from a standing figure of him wearing a toga or a cuirass.

-

✴According to Antonio Giuliano (referenced below), the style of the recutting is very close to the carving of the Arch of Constantine (312-5 AD) in Rome.

The bust is now in the Museo Nazionale Etrusco, Viterbo.

Pierre Gros (referenced below, 2013, p. 99) believed that, when the bust of Constantine had been installed in the basilica (which he dated to ca. 315 AD), the basilica itself had still maintained its civic function. Since the apse of the modified structure adversely affected the road here, he argued that the building of the apse (and the reduction in the width of the covered building) occurred a few decades later, when the civic basilica was adapted for use as a church. Thus he rejected (in my view incorrectly) the suggestion of Pietro Tamburini (discussed below) that there was an interim phase, immediately after the restructuring of the basilica, during which it served as the templum Flaviae gentis.

In my view, the road here could have lost it importance at any time after the fire of 270 AD (since nearby buildings that were damaged in the fire were never rebuilt). Thus, Pietro Tamburini’s hypothesis should be discussed on its own merits. Before doing so, it is necessary to consider the historical context in which the bust of Octavian was recut to portray Constantine.

Bust of Constantine (Recut in 315 AD)

Constantine famously marched on Rome in 312 AD and “liberated” it from the “usurper” Maxentius. This régime change necessitated the rapid realignment of overt political allegiance, as the Roman and provincial élites rushed to proclaim their undying allegiance to Constanine, whom the Senate now acknowledged as “primi nominis” (the most senior of the three Augusti).

In this febrile climate, Caius Ceionius Rufius Volusianus, who was Constantine’s Urban Prefect in 313-5 AD and Consul of 314 AD, erected a statue of Constantine in the Forum of Trajan in Rome. Both the statue and its base are now lost, but a transcription of its inscription (CIL VI 1707, LSA-837) survives. The LSA database translates it as follows:

-

To our lord, restorer of the human race, extender of the Roman empire and dominion, founder of eternal security, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, fortunate, greatest, pious, forever Augustus, son of the deified Constantius forever and everywhere venerable. Caius Ceionius Rufius Volusianus, of clarissimus rank, consul, urban prefect, judge in place of the emperor, dedicated to his divine spirit and majesty.

This statue was surely erected ahead of Constantine’e arrival in Rome in July 315 AD for the celebration of his decennalia. Volusianus proclaims himself to be dedicated to “the divine spirit and majesty” of Constantine, the son of divus Constantinus. Before Constantine left Rome on 27th September 315 AD, he replaced Volusianus as Urban Prefect with Caius Vettius Cossinius Rufinus. According to Timothy Barnes (referenced below, 1975, at p. 47), Volusianus was exiled shortly after his dismissal, apparently by his enemies in the Senate (possibly while Constantine was still in Rome), and never emerged from this disgrace.

The point that I want to make here is that both Volusianus and Vettius Rufinus had previously been partisans of Maxentius, and they therefore needed to be very public in demonstrating their changed allegiance. As Noel Lensk (referenced below, at pp 212-3) observed, in relation to the latter:

-

“[Constantine’s new Urban Prefect,] Vettius Rufinus ... was a former partisan of Maxentius, by whom he had been granted no fewer than five offices. ... Vettius Rufinus was a committed pagan, a devotee of the sun god in his capacity as pontifex dei solis, in addition to serving in the college of augurs and as salius palatinus. This combination of priestly offices, and especially the augurate, make it likely, although not certain, that Vettius Rufinus ... [had] numbered among those senators who had advised Maxentius on strategy in October 312 AD. Even so, Constantine saw fit to retain him as Urban Prefect for nearly a year (20th August 315—4th August 316 AD), to promote him to comes Augusti, and to appoint him consul for 316 AD.”

We know from the inscription (CIL X 5061; LSA-1978) on the base of a statue to him from Atina in Campania that Vettius Rufinus had previously been:

-

✴corrector (governor) of Campania, probably in 312 AD; and

-

✴corrector (governor) of Tuscia et Umbria, probably in ca. 311 AD

As discussed in my page on Volsinii in the Triumviral Period, the bust of Octavian had probably been associated with the revived Etruscan Federation. Its original location is a matter for conjecture:

-

✴Its Spoletan prototype was found in the Roman theatre there: the similar head from Volsinii might also have been in the putative theatre in the original forum of Volsinii .

-

✴Another possibility is that the statue was originally in the putative Temple of Nortia at Campo della Fiera: a precedent for this might be the temple of Fortuna Augusta at Pompeii, the cella of which contained a cult statue of Fortuna (a Roman equivalent of Nortia), along with statues of Augustus and other members of the imperial family in the side niches.

I suggest that the recut statue probably retained this location, and that Constantine thus symbolically inherited Octavian’s relationship with the Etruscan Confederation at Volsinii. It is even possible that Constantine visited Volsinii, perhaps accompanied by Vettius Rufus, after he left Rome for Milan

Basilica Forense (again)

As noted above, Pietro Tamburini (referenced below, at pp. 558-61) suggested that there had actually been an intermediate stage between:

-

✴the building of the apse of the basilica and the reduction in the width of the covered building in ca. 315 AD AD; and

-

✴its conversion into a church, which he dated to the second half of the century;

during which it served as a temple to the cult of Constantine’s deified ancestors: it would have contains a number of dynastic statues, which probably included the recut statue of Constantine himself. His arguments (with which I substantially agree) are discussed in my page on the Rescript of Constantine at Hispellum.

It is possible that two inscriptions relating to other members of Constantine’s family were associated with this putative temple to the gens Flavia:

-

✴Luigi Sensi (referenced below at p. 370, note 26) recorded a fragmentary inscription that had been published in 1919 by Goffredo Bendinelli following excavations at Bolsena. This inscription might have referred to Crispus, the eldest son of Constantine, who held the rank of Caesar from 317AD until his execution in 326 AD:

-

[...]iuli/ [..].us victor [..]./ [...]s.Crispum [...]

-

This inscription, which might have commemorated Crispus’ victory over the Franks in ca.320 AD, might have been erected in or near the temple, albeit that it would have been removed after his disgrace and execution.

-

✴An inscription (CIL XI 2697; EDR 126862; LSA-1625) on the base of a statue that, according to LSA, was found at Bolsena (unfortunately, in an unknown location), and which is now in the loggia of Palazzo Soliano, Orvieto, commemorated the Emperor Constantius :

-

Imp(eratori) Caes(ari) / Flavio Cons/tantio Pio / Fel(ici) Invicto / Aug(usto) [...]

-

To the Emperor Caesar Flavius Constantius, pious, fortunate, unconquered Augustus

-

The absence of the epithet “divus” suggests that this was a statue of a living emperor, who could have been: Constantine’s father, Constantius I (305-6 AD); or Constantine’s son, Constantius II (337-61 AD).

These inscriptions might provide support for the hypothesis of the existence of a temple devoted to Constantine’s deified ancestors at Volsinii, although the complete uncertainty about the find spots precludes more than a tentative suggestion.

Read more:

E. Zuddas, “La Praetura Etruriae Tardoantica”, in

G. A. Cecconi et al. (Eds), “Epigrafia e Società dell’ Etruria Romana (Firenze, 23- 24 ottobre 2015)”, (2017) Rome, pp. 217-35

G. della Fina and E. Pellegrini (Eds), “Da Orvieto a Bolsena: un Percorso tra Etruschi e Romani”, (2013 ) Pisa. In particular:

P. Gros, “La Nuova Volsinii: Cenno Storico sulla Città”, (pp 88-105)

A. Ambrogi and I. Caruso, “Arte di Età Imperiale: i Ritratti di Costantino e di Domizia Longina”, (pp 326-8)

A. Ambrogi, “Ritratto di Augusto-Costantino”, in

A. Bravi (Ed.), “Aurea Umbria: Una Regione dell’ Impero nell’ Era di Costantino”, Bollettino per i Beni Culturali dell’ Umbria (2012) pp 128-30

T. Barnes, “Constantine: Dynasty, Religion and Power in the Later Roman Empire”, (2011) Chichester

N. Lenski, “Evoking the Pagan Past: Instinctu Divinitatis and Constantine’s Capture of Rome”, Journal of Late Antiquity, 1:2 (2008) 204-57

P. Tamburini, “Bolsena: Emergenze Archeologiche a Valle della Città Romana”, in

G. della Fina (Ed.), “Perugia Etrusca”, Annali della Fondazione per il Museo ‘Claudio Faina’, 9 (2002) pp 541-80 A. Giuliano, “Augustus–Constantinus”, Bollettino d 'Arte, 69 (1991) 3-10

T. Barnes, “The New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine”, (1982) Cambridge (MA) P. Gros and L. Mascoli, “Bolsena I: Scavi della Scuola Francese di Roma a Bolsena

(Poggio Moscini): Guida agli Scavi”, Mélanges d' Archéologie et d' Histoire, 6 (1981)

W. Harris, “Rome in Etruria and Umbria”, (1971) Oxford

Ancient History: Velzna/ Volsinii Destruction of Velzna

Volsinii (Bolsena): Republican Period; TriumviralPeriod;

Early Empire; Imperial Period; Late Empire;

Rescript of Constantine at Hispellum (ca. 335 AD)

Return to the page on History of Orvieto.