Submission to Rome

In his oration ‘Pro Balbo’, Cicero recorded his defence of Lucius Cornelius Balbus, a Spaniard who was given Roman citizenship by Pompey in 72 BC and later prosecuted for allegedly having claimed it illegally. Cicero used a number of precedents, which included some in which “the great man” Marius had awarded Roman citizenship to soldiers from allied cities who had distinguished themselves in the service of Rome in 100 BC. These included:

-

“... Marcus Annius Appius of Iguvium, a most gallant man, and one endured with the most admirable virtue ...” (46:46).

Later in the speech, Cicero claimed that Marius would have testified, had he been before the court, that:

-

“In neither in the treaty with Iguvium nor that with Camerinum was there any saving clause stipulating that the rewards of valour should not be bestowed on their citizens by the Roman people” (46:47: I have taken this translation from Guy Bradley, referenced below, at p. 119, noter 54).

We know that Rome’s treaty with Camerinum was an equal treaty and that it was probably negotiated after the Romans had first crossed the Ciminian forest in ca. 310 BC. However, neither the date of Iguvium’s treaty nor its terms are known, although it was probably in place by the time that the town began to mint its own coins (below).

Coinage

Only three Umbrian towns are known to have minted coins in the 3rd century: Ariminum, Iguvium, and Tuder. The coins of the latter two, which were bronze, used the Etruscan pound but followed Roman practice in subdividing it into twelve. The coins of Iguvium carried the legend IKVVINI. Guy Bradley (referenced below, at p. 186) suggested that:

-

“The most likely issue date for these weights is the First Punic War [264 - 41 BC], assuming that they derive from the Roman issues of cast bronze of the early 3rd century.”

Via Vittorina

The city benefited thereafter from the construction of Via Vittorina, which linked it to Via Flaminia at a new settlement called Helvillum Vicus to the east (at modern Fossato di Vico). This road ran in roughly this direction of what is now Via Frate Lupo.

Municipalisation

Two fragments from the lost book of Cornelius Sisenna relate to Iguvium:

-

“... and so, on the next day, he came on the envoys returning to Iguvium”; and

-

“... then, after he made an announcement of this deed before the people of Iguvium and Perusia, ... ”

These fragments are translated in the book edited by T. J. Cornell (referenced below, Volume II, at respectively: F. 62, p. 635; and F 84, p. 645 ). They came from Book IV, which Edward Bispham (referenced below, at p. 184) asserted related to events of 89 BC. He suggested (at p. 186) that both Iguvium and Perusia might have revolted in 90 BC and thus had been excluded from the grants of citizenship made in that year: instead they had to await further legislation in the following year. Iguvium subsequently became a municipium and was enrolled in the Clustumina tribe. It was at this time that the monumentalisation of the settlement began in earnest (see below).

In 49 BC, Pompey's forces occupied it, but they fled when attacked by a smaller force loyal to Caesar because they feared the hostility of the inhabitants. We might presume that the city subsequently prospered accordingly.

The urban centre of Iguvium probably developed at about this time in the area of some 25 acres now known as Guastuglia, on the plain below Monte Ingino. This area (now outside Porta degli Ortacci extends bounded by Viale del Teatro Romano, Via Matteotti, Viale Parruccini, Via Ubaldi and Via Perugina).

Renovations of the theatre here and its associated temples [including the temple of Jupiter Appenninus, of which traces survive - see below] during the reign of the Emperor Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD) might well have been part of a program to revive the ritual legacy of ancient Ikuvina.

The fine sculpture on display in the Museo Civico indicates that Iguvium prospered throughout the Roman period, and excavations indicate that it was in continuous use until at least the 4th century AD.

Urban Development

The most important survival of Roman Iguvium is the Roman theatre. Two inscriptions (CIL XI 5820) from this period in the Museo Civico record the civic works of Gnaeus Satrius Rufus, one of the four magistrates of Iguvium at this time. The inscriptions, which were found near the theatre (one in the 16th century and one in 1863), seem to have carried identical texts, although the second is more complete. Apparently, Gnaeus roofed the basilica (foyer) of the theatre and paved the floors. He also renovated a temple to Diana that might well have been part of the complex, and made a number of other donations for civic purposes including money to finance games (ludi victoriae Caesaris Augusti) held in honour of Augustus.

[Recent excavations in Guastuglia have unearthed the remains of an urban temple and the probable site of the forum.]

The exhibits in the Museo Civico include finds from what was probably the site of the public baths on nearby Via degli Ortacci.

A stretch of Roman terrace that supported the centre of the city is visible to the southwest of the theatre.

The city was surrounded by an almost continuous ring of necropoles, the most important of which were those:

-

✴near the church of San Biaggio and the Roman Mausoleum (1st century BC) in Via Ubaldi; and

-

✴near Santa Maria della Vittoria.

Other necropoles have been excavated:

-

✴near Santa Maria del Prato,

-

✴in località Zappacenere; and

-

✴in località Fontevole.

Suburban Temples

Remains of temples (2nd century BC) at Monteleto (on the left) and Nogna,

both from photographs displayed in the Antiquarium

This road from Gubbio towards Umbertide passes the sites of two temples that were built on the borders of Roman Iguvium:

-

✴the so-called Temple of Diana at Monteleto, some 7 km from Gubbio; and

-

✴another temple at Nongna (Castello Cortevecchio), which is reached by a right turn some 200 meters further on.

[San Pietro in Vigneto]

Temple of Jupiter Apenninus

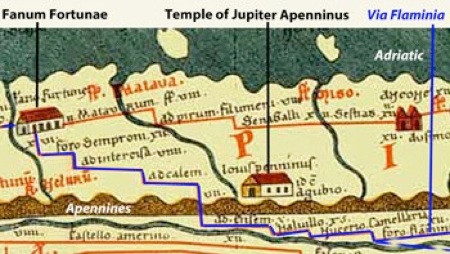

Tabula Peutingeriana (depicted in the website by the

Biblioteca Augustana der Fachhochschule, Augsburg)

Claudian, writing about a journey of the Emperor Honorius from Ravenna to Rome in 404 AD, has him traveling through an arch in the living rock of the Apennines along a “path through the mountain's very heart, rising above the temple of Jove and dizzy altars set up by the shepherds of the Apennines”.

This temple is marked on the Tabula Peutingeriana (above), a copy of a map that included the Via Flaminia, the original of which probably dates to ca. 250 AD. This document clearly links the temple to Gubbio: “Iovis Penninus id est Agubio” (Jove Apenninis, i.e. Gubbio). The temple is otherwise known only from two inscriptions in archaic Latin that were apparently found at Piaggia dei Bagni, near the cemetery of Scheggia during roadworks in 1667:

-

✴CIL XI 5803 (1st century AD), which is now in Museo Civico, Verona, reads

IOVI / APENINO

T.VIVIUS CAR’MOGENES (ET)

SULPICIA EU(PHRO)/SYNE CONIUX

V.S.D.D.

-

and records a supplication to Jupiter Apenninus by Titus Vivius Carmogenes for his wife Euphrosyne.

-

✴CIL XI 5804 (2nd century AD), which was in the Museo di Antichita, Turin until 1901, is recorded as:

I. O. M. S.

PRO SALUTE

CN. ACONI CRESCENT[is]

ARA(M) POSUIT/ BAEBIDIA POTESTAS

-

This second inscription came from a small altar (“ARA”) found nearby, next to a marble vessel for ritual purification. “O. M. S” signifies Jupiter Optimus Maximus (best and greatest).

(I am grateful to Dottore Federico Uncini for this information).

According to Historia Augusta, there seems to have been an oracle here at the time of the Emperors Claudius II (268-70 AD) and of the usurper Firmus (died 273 AD).

Some scholars have suggested that this could be the site of the “Fisan Mount” mentioned in the Iguvine Tables.

Read more:

T. J. Cornell, “The Fragments of the Roman Historians”, (2013) Oxford

E. Bispham, “From Asculum to Actium: The Municipalisation of Italy from the Social War to Augustus”, (2008) Oxford

S. Sisani, “Tuta Ikuvina: Sviluppo e Ideologia della Forma Urbana a Gubbio”, (2001) Rome

G. Bradley, "Ancient Umbria", (2000) Oxford

C. Malone and S. Stoddart (Eds.), "Territory, Time and State", Cambridge (1994)

Return to History of Gubbio.