Possible self-portrait (ca. 1500)

Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Raffaello Sanzio was born in Urbino. His mother died when he was eight, his younger brother and sister both followed shortly afterwards, and his father, the artist Giovanni Santi, died when he was eleven. He had a stepmother by that time, but he went to live with an uncle and they jointly inherited his father’s workshop in Urbino.

Giovanni Santi, who had been a court artist at Urbino, had also written the rhymed “La Vita e le Gesta di Federico da Montefeltro, Duca d’ Urbino” (ca. 1482). This included verses on the most important painters of his day, and it was here that Perugino was first dubbed “il divin pittore”. Giorgio Vasari claimed that Giovanni sent the young Raphael (who would have been no older that eleven) to Perugia to join Perugino’s workshop. There is, however, no other evidence for any relationship between Perugino and Raphael before ca. 1500, albeit that they were closely associated for a short period thereafter (see below).

In fact, nothing is known about Raphael’s training, although it seems likely that it began in his father’s workshop.

-

✴Evangelista di Pian di Meleto, who was first documented in this workshop in 1483, was still associated with Raphael some years after his father’s death (see below): he had presumably helped in the training of the young orphan, and it is unlikely that he was the only member of the workshop to have done so.

-

✴Timoteo Viti, who replaced Raphael’s recently-deceased father as the principal artist at court of Urbino in 1495, was also a long-standing friend. Viti worked under Raphael in Rome in ca. 1514 and late and came to own the most important group of his studio drawings.

-

✴[Girolamo Genga ??]

Raphael’s earliest documented work is almost certainly the altarpiece (1500-1) of the Coronation of St Nicholas of Tolentino for Sant’ Agostino, Città di Castello (see below). Despite the fact that he was only seventeen, he was termed "magister" in the contract for it, and named before his older collaborator, Evangelista di Pian di Meleto. This suggests that he had already matriculated and that he was by this time the senior of the two, at least in the context of this commission.

There is no reason to think that Raphael had left Urbino at the time that he painted the Sant’ Agostino Altarpiece: Evangelista di Pian di Meleto was certainly still based there. However, Cesare Borgia invaded the duchy in 1502, and it might have been this event that caused his departure.

According to Vasari, Pintoricchio invited Raphael to Siena, “knowing him to be an excellent draughtsman”, and he made some of the “drawings and cartoons” for Pintoricchio’s fresco cycle (1503-08) in the Piccolomini Library of the Duomo there. Preparatory drawings for these frescoes that are attributed to Raphael include:

-

✴[one that is now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence]; and

-

✴another that was in Palazzo Baldeschi Cennini, Perugia from 1586 until early in the 20th century, which is now in the Pierpoint Morgan Library, New York

Raphael seems also to have assisted Pintoricchio at this time with the design of the altarpiece (1502-5) of the Coronation of the Virgin for Santa Maria della Pietà, la Fratta (see below).

Raphael was documented in Perugia in early 1503, and he received his first important commission in that city, the so-called Oddi Altarpiece (see below), at about this time. He painted two more altarpieces for churches in Città di Castello (see below) in ca. 1503-4, both of which betray a close association with Perugino. He also seems to have developed close links with the influential Alfani family, for whom he painted the so-called Connestabile Madonna (ca. 1504).

In 1504, Giovanni della Rovere, la Prefetessa, who was the the sister-in-law of Duke Guidobaldo da Montefeltro (now safely, if temporarily, reinstated as Duke of Urbino), supplied Raphael with a letter of recommendation to Piero Soderini, the Gonfaloniere of Florence, where Raphael wished to study. He is subsequently recorded twice in Perugia (in 1505 and 1506) and twice in Urbino (in 1506 and 1507). However, he signed a letter to his uncle in 1508 as “your Raphael, painter in Florence”, and he seems to have spent enough time in the city in 1504-8 to absorb a great deal from its art: his fresco in San Severo, Perugia and his Baglioni Altarpiece (see below for both) belong to this period. He might also have begun the design for a major civic commission in Perugia, perhaps inspired by Soderini’s similar commission from Michelangelo for Palazzo Vecchio, Florence: if so, the only remaining evidence is a preparatory drawing for a fresco of the Siege of Perugia (see below), which is now in the Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Pope Julius II called Raphael to Rome in 1508, when he was still only 25 years old, and he spent the remaining twelve years of his life there. When Bramante died in 1514, Pope Leo X appointed him as capomaestro of St Peter's. He had become one of the leading Italian artists by the time of his early death. At least two major Perugian commissions that were left unfinished by Raphael’s move to Rome were completed after his death:

-

✴the ageing Perugino painted the lower part of the fresco in San Severo in 1521: and

-

✴Raphael’s younger associates painted the altarpiece (1523-5) of Coronation of the Virgin for the nuns of Santa Maria di Monteluce (see below), which they had commissioned from him in 1503.

Città di Castello

The departure of Luca Signorelli from Città di Castello in ca. 1498 seems to created an opportunity for the young Raphael, who secured a number of important commissions in the city in the following six years.

Gonfalone della Santissima Trinità (ca. 1503)

This two-sided processional banner was probably commissioned by the Confraternita della Trinità, which met in the Chiesa della Santissima Trinità. It was first documented there in 1627, with an attribution to Raphael, and again a year later, when it was deemed to be too damaged to be used in processions. The two sides were subsequently separated and were used as altarpieces at the sides of the high altar of the church until 1855, when they suffered the first of a series of attempted restorations. The most recent of these, in 1952 and 1983, were of very high standard, but much of the damage could not be reversed. The panels passed to the Commune in 1860 and are now in the Pinacoteca Comunale.

The panels depict:

-

✴Holy Trinity (God the Father, the Crucified Christ and a dove representing the Holy Spirit) with SS Sebastian and Roch; and

-

✴the creation of Eve from Adam’s rib, with two angels.

Each retains its original gilded border.

A preparatory sketch for the figure of God the Father in the panel on the right survives in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. The same sheet contains a sketch of a detail of the altarpiece (1498) of the Martyrdom of St Sebastian by Luca Signorelli in San Domenico, Città di Castello, to which Raphael’s Mond Crucifixion (1503 - see below) formed a pendant. Raphael presumably executed these sketches while he was in San Domenico in order to plan his design for the altarpiece, which suggests that the banner was also painted in ca. 1503.

From Città di Castello

Coronation of St Nicholas of Tolentino (1500-1)

Surviving fragments at:

Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Musée du Louvre,

Brescia Naples Paris

This altarpiece is almost certainly the work that the wool merchant, Andrea di Tommaso Baronci commissioned in 1500 from Raphael and Evangelista di Pian di Meleto for his chapel in Sant’ Agostino, and for which he paid on its completion in 1501. If the link between the altarpiece and the documents is correct, this was Raphael’s earliest documented work. Despite the fact that he was only seventeen, he was termed "magister" in the contract, and named before his older collaborator (as noted above). In view of his age, the goldsmith Battista di Florido acted as guarantor for him: Batista’s son, an artist who became known as Francesco Tifernate, was greatly influenced by Raphael’s work in the city.

The altarpiece was (like the church itself) in an earthquake in 1789. The then-owners of the chapel, who had obstructed plans to sell it in 1788, now agreed to the sale of what remained in order help rebuild the church.

-

✴Pope Pius VI acquired the four surviving fragments from the upper part of the main panel. There were looted during the French occupation of Rome in 1798 and subsequently dispersed. They are illustrated above, with captions that indicate their respective current locations.

-

✴Two predella panels depicting miracles of St Nicholas of Tolentino, which might have belonged to this altarpiece or alternatively to the Capra Altarpiece by Perugino, found their way into the collection of Ralph Harman Booth (died 1931). His widow gave them to the Institute of Arts, Detroit, and they are illustrated in the institute's website.

-

✴Preparatory sketches for it survive in the Musée des Beaux Arts, Lille and the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

-

✴Ermenegildo Costantini, who was at work in the Duomo at the time of the earthquake and who subsequently fled to Rome, painted a loose copy of its lower part in 1791. This is now in the Pinacoteca Comunale (illustrated here).

-

✴Luigi Lanzi gave a description of it in a book that was published in 1795.

From these clues, it can be established that:

-

✴St Nicholas of Tolentino stood on a prostrate figure of Satan in the centre of the lower part of the composition;

-

✴there were probably two angels to each side of him (fragments of two of which survive); and

-

✴the upper part of the work contained three figures, each of which held a crown:

-

•God the Father in a mandorla, with a half-length figure of the Virgin to the left (now seen in the third surviving fragment); and

-

•a lost figure of St Augustine to the right, which balanced the figure of the Virgin.

A diagram of a proposed reconstruction is presented at page 100 of the catalogue of the 2004 exhibition in London referenced below. It is clear from the size of the figures that survive that the original altarpiece must have been huge.

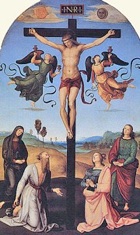

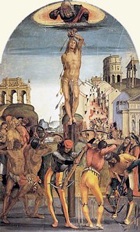

Crucifixion with Saints (ca. 1503)

This altarpiece, which is signed by Raphael, came from the Cappella di San Girolamo in San Domenico. Its original frame, which survives there, contains the Gavari arms and an inscription along the bottom that reads:

HOC . OPVS . FIERI . FECIT . DNICVS / THOME . DEGAVARIS . MDIII

(Domenico di Tommaso Gavari had this work made: 1503)

In his will of 1511, Domenico Gavari requested burial in this chapel.

The circumstantial evidence provided by the frame suggests that Domenico Gavari commissioned the altarpiece from Raphael in ca. 1503. Its main panel depicts the Crucifixion with the Virgin and Saint John the Evangelist, and with SS Jerome and Mary Magdalene kneeling to the sides of the cross. Two angels catch the blood from the wounds in Christ’s hands, with symbols of the sun and the moon above. The scene is set in a landscape and all of the figures seem to be lost in contemplation.

This main panel was sold in 1808 and subsequently had a succession of private owners. It is now known as the Mond Crucifixion because the last of these, Ludwig Mond, bequeathed it to the National Gallery, London in 1924. The predella panels, which the friars seem to have been given away in the 17th century, probably depicted episodes from the life of St Jerome. They may well have included:

-

✴a panel of Eusebius of Cremona using St Jerome's cloak to raise three men from the dead, which is now in the Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon; and

-

✴the panel of St Jerome saving Silvanus from decapitation and the miraculous decapitation instead of the heretic Sabinianus, which is now in the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh.

Marriage of the Virgin (1504)

The cult of St Joseph had taken root in Umbria following the Perugian’s acquisition in 1473 of a relic supposed to have been the Virgin’s wedding ring. This ring was kept in the Cappella di Sant' Anello in the Duomo of Perugia, and the composition of Raphael’s altarpiece in Città`di Castello was based on that by Perugino in the chapel in Perugia. The altar for which Raphael’s version was painted was on the left wall, at the dividing line between the upper part of the nave, which was reserved for men, and the lower part, which was reserved for women. This could explain why Raphael reversed Perugino’s composition, placing the Virgin and her female entourage towards the women’s part of the church.

Duke Guidobaldo II delle Rovere tried unsuccessfully to buy Raphael’s altarpiece in 1571. It is surprising that the French did not earmark it for confiscation under the Treaty of Tolentino (1797). However, Count Giuseppe Lecchi, who entered Città di Castello in 1798 at the head of the troops of the Cisalpine Republic, took possession of it and sent it to his home in Brescia. He claimed to have been given it as a gift, but he had probably demanded it as an alternative to the sack of the city. This despoilation was one of the sparks that led to a subsequent riot, after which the city was sacked in any case.

The collector Giacomo Sannazzari bought the altarpiece in ca. 1801 and left it to the Ospedale Maggiore, Milan when he died in 1804. Governor Giuseppe Beauharnais bought it for the Accademia di Brera two years later, and it is now in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan.

From Foligno

Madonna di Foligno (ca. 1511)

The nuns resisted a series of offers to buy the painting over the centuries. It is surprising that the French did not earmark it for confiscation under the Treaty of Tolentino (1797). However, Napoleon's commissioner, Jean-Antoine Gros subsequently added it to the list, and the vociferous objections of the people of Foligno were to no avail. Antonio Canova recovered it in 1815. However, it became the subject of a dispute between the nuns of Sant' Anna and the canons of the Duomo, Foligno. The nuns therefore decided to sell it to Pope Pius VII. It is now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana and is illustrated in the Vatican website.

-

✴A copy (17th century) that is attributed to Giuseppe Cesari, il Cavalier d’ Arpino formed part of the bequest by the heirs of the Roscioli family to the Duomo in 1703. It seems that either Bartolomeo or Giovanni Maria Roscioli commissioned it when the original altarpiece was in Sant’ Anna. It is now in the Museo Diocesano.

-

✴A copy (18th century) hangs on the wall of the apse of the Duomo.

The altarpiece depicts the Madonna and Child seated on a cloud in front of the sun; this may be a reference to the "woman clothed by the sun" in Revelations 12:1.

-

✴St Jerome commends the kneeling donor to the Virgin. Giorgio Vasari commented that the portrait of the donor was "as lifelike as any ever painted".

-

✴The kneeling St Francis commends the viewer to the baby Jesus.

-

✴St John the Baptist draws the viewer's attention to this apparition.

The scene is set before a cityscape of Foligno. Sigismondo is thought to have commissioned the work in thanks for the survival of his palace in the city (now Palazzo Gentili Spinola - see Walk II) after it had been struck by a ball of lightening, and this event seems to be depicted here. The small angel in the centre of the composition holds a plaque that was probably intended originally to bear an inscription.

Perugia

Raphael was documented in Perugia in January and again in March, 1503.

Trinity with saints (ca. 1505-21)

Upper Part (ca. 1505)

According to an inscription to the left of this fresco, Raphael painted the upper part in 1505, in the time of the Prior Ottaviano di Stefano da Volterra. Some authorities query this early date, given the mature style of the fresco, but others see no reason to dispute it. This was the only fresco commission that Raphael ever won in Perugia, and it is the only certain work of his that is left in the city. It was incomplete when he left the city for Rome, but the monks did not give up hope of further progress until he died there in 1520.

This upper part of the fresco depicts the Trinity (although the figure of God the Father is ruined) and angels, with six saints that are identified by inscriptions:

-

✴SS Maurus, Placidus and Benedict on the left; and

-

✴SS Romuald, Benedict Martyr and John the Monk on the right.

(The last two were Camaldolesian monks from Benevento who were martyred in Poland in 1005 and whose cult was confirmed in 1508).

The inspiration for this composition seem to have come from Fra Bartolomeo’s fresco of the Last Judgment for the Ospedale di Santa Maria Nuova, Florence, which Mariotto Albertinelli finished in 1501. (This damaged fresco is now in the Sala del Lavabo, Museo di San Marco, Florence). As noted above, Raphael seems to have spent a good deal of his time inFlorence in 1504-8.

Lower Part (1521)

After the death of Raphael, the monks turned to the aged Perugino to complete the work. The inscription to the right records that he executed the saints to the sides of the niche in 1521, in the time of the Prior Silvestro di Stefano da Volterra. Again, these saints are identified by inscription:

-

✴SS Scholastica, Jerome and John the Evangelist on the left; and

-

✴SS Gregory the Great, Boniface and Martha on the right.

(St Boniface was a Camaldolesian monk and relative of the Emperor Otto III who was martyred in Poland in 1009).

From Perugia

Oddi Altarpiece (ca. 1503)

The altarpiece is generally accepted to have been painted early in Raphael's career: its commission might have coincided with the short period in 1503 during which the Oddi exiles were allowed back into Perugia under the protection of Cesare Borgia, although it is possible that the female members of the family remained in Perugia during the exile of their men. Whatever the merits of these arguments, scholars generally accept the date ca. 1503 on stylistic grounds.

The Oddi Altarpiece was one of three works in the San Francesco al Prato that Napoleon's commissioner, Jacques-Pierre Tinet selected for confiscation under the Treaty of Tolentino (1797). Antonio Canova recovered it in 1815, when it was secured for the Pinacoteca Vaticana.

The main panel links two scenes from the narrative of the death of the Virgin:

-

✴In the lower part of the composition, the Apostles surround the empty tomb. St Thomas stands behind it, flanked by SS Peter and Paul and holding the Virgin's girdle.

-

✴Above, Jesus crowns the Virgin on a bank of cloud, surrounded by musical angels. The upper part of the composition was probably inspired by the altarpiece (1486) of the Coronation of the Virgin that Domenico Ghirlandaio had painted for the high altar of the church of the Observant Franciscans of San Girolamo, Narni. As noted below, Raphael seems to have assisted at this time with the design of Pintoricchio’s Coronation of the Virgin (1502-5) for the Observant Franciscans of Santa Maria della Pietà, la Fratta (now Umbertide): this work was explicitly required to reflect Ghirlandaio’s altarpiece at Narni.

The predella panels, which are displayed separately in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, depict:

-

✴the Annunciation;

-

✴the Adoration of the Magi; and

-

✴the Presentation at the Temple.

Conestabile Madonna (ca. 1504)

There is additional circumstantial evidence that the Alfani family had originally commissioned the painting. The link is the Coronation of the Virgin (1523-5), which Battista Alfani, the Abbess of Santa Maria di Monteluce commissioned from Raphael in 1504 (see below). Her nephew Alfano di Diamante Alfani, who was an important official at the papal court, knew the artist and witnessed the new contract that he signed with the nuns in Rome in 1516.

The painting passed to the collection of Connestabile della Staffa family in the early 17th century and was housed in Palazzo Conestabile della Staffa. It was sold to Tsar Alexander II of Russia in 1870 and entered the Hermitage Museum in 1880. The picture is in the form of a tondo that was originally on a panel that was integral to an ornately gilded frame. The tondo was subsequently transferred to canvas and is now in a frame that might be the original one. It depicts the half-length Madonna and Child set in a landscape. Both the Madonna and the baby Jesus attentively study the book that the former is holding.

Colonna Altarpiece (ca. 1504)

There is no surviving documentation relating to the original commission of the altarpiece. Most authorities date it to ca. 1504, and its commission might have been associated in some way with the death of Sister Ilaria in ca. 1503. Giorgio Vasari saw it in an unspecified location in Sant’ Antonio, probably during his stay in Perugia in 1566, observing that the sisters held it in great veneration. His attribution of it to Raphael is universally accepted. Cesare Crispolti made clear in his guide (1597) that it was in the nuns’ inner church.

The altarpiece was painted on a single piece of wood, except for the figures of SS Francis and Antony (see below), which presumably stood forward of the rest on the base of the frame. It remained in situ until 1663, when the impoverished sisters had it sawn into its component parts so that they could be sold.

-

✴The Colonna family bought the main panel and the lunette in 1677 (which accounts for the usual appellation of the work). These panels had a number of subsequent owners until 1902, when J. P. Morgan bought them at huge expense. He gave them to the Metropolitan Museum, New York in 1916:

-

•The main panel depicts the Madonna and Child enthroned with saints. The baby Jesus blesses the infant St John the Baptist: both are fully clothed, a stipulation of the nuns according to Vasari. The flanking saints are:

-

-SS Peter and Catherine of Alexandria to the left, and

-

-St Paul and another female martyr to the right. Vasari describes this fourth saint as St Cecilia, but other documents relating to the later sale of the work identify her as St Margaret. It is possible that she is St Margaret of Antioch, and that she was included in memory of Sister Ilaria, whose given name was Margherita.

-

•the lunette above the main panel depicts God the Father with two angels.

-

✴Queen Christina of Sweden bought the predella panels and the panels of SS Francis and Antony of Padua in 1663. They stayed together until 1702 but were then dispersed:

-

•the central panel (illustrated above), which depicts the Procession to Calvary, is in the National Gallery, London;

-

•the lefthand panel, which depicts the Agony in the Garden, is in the Metropolitan Museum, New York;

-

•the right panel, which depicts the Pieta, is in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston; and

-

•the outer panels of SS Francis and Antony of Padua are in the Dulwich Picture Gallery, London.

Ansidei Altarpiece (1505)

Vasari attributed the altarpiece to Raphael, and this has been universally accepted. It has been suggested that there are one or perhaps two further numerals after the date “MDV” on the Virgin’s left sleeve: however, this is not obviously the case, and stylistic considerations support the date 1505.

The altarpiece depicts the Madonna and Child enthroned with SS John the Baptist and Nicholas of Bari (the name saints, respectively, of Nicolò and his son Giovanni Battista). These figures are set in a fictive chapel that seems to have been inserted (albeit seamlessly) into the composition at a late stage because the real "chapel" for which the altarpiece was destined was in fact on a pilaster in the nave. The fictive architecture would have asserted the importance of the location in the context of the grander recessed chapels further down the left side of the nave.

The altarpiece probably remained in its original location until the remodelling of the church that began in 1763. The Servites sold the main panel and a predella panel of St John the Baptist preaching to the family of the 3rd Duke of Marlborough in the following year. Unfortunately, the other predella panel, which depicts St Nicholas of Bari saving a sinking ship, has been lost. The surviving panels were displayed at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire until 1883, when they were "saved for the nation". They are now in the National Gallery, London.

Siege of Perugia (ca. 1505)

Tom Henry (in an article referenced below, which is available, with illustrations, on his Casa Nova Umbria website) identified a drawing in the Musée du Louvre, Paris (inventory number 3856r), which is attributed to Raphael, as a depiction of Totila’s siege of Perugia, which led to the execution of St Herculanus in 552 AD. Henry drew the parallels between this work and the frescoes (late 15th century) on this subject by Benedetto Bonfigli in the chapel of Palazzo dei Priori, Perugia (now part of the Galleria Nazionale).

Henry suggested that this drawing might have been inspired Michelangelo's study (1504) for the Battaglia di Cascina, a fresco that Piero Soderini, the Gonfaloniere of Florence, had commissioned for Palazzo Vecchio. If a similarly major civic commission had indeed been planned in Perugia at this time, it would almost certainly have been for the Palazzo dei Priori. It is not difficult to imagine how such a project might have been derailed by the political instability in Perugia in the early 16th century. However, it has to be said that there is no direct evidence that throws any light on the matter.

Monteluce Altarpiece (1505-25)

Contract of 1505

The “Memoriale di Santa Maria di Monteluce” records that the nuns of Santa Maria di Monteluce decided to commission a new altarpiece for the high altar of their outer (public) church in 1503. They asked the friars at the Convento di Monteripido to recommend “il maestro il migliore” (the finest master) from whom they might commission it, and the friars recommended Raphael. The nuns therefore signed a contract in 1505 with Raphael and Berto di Giovanni. They paid a deposit using a bequest from Sister Illuminata de Perinello, and Raphael promised to deliver the work within two years.

The contract had a number of interesting features:

-

✴It specified that the altarpiece would match in quality or surpass that of the Coronation of the Virgin that Domenico Ghirlandaio had painted in 1486 for the high altar of the church of the Observant Franciscans of San Girolamo, Narni. Specifically, it would match the Narni altarpiece in terms of “perfection, proportions, quality, and condition ... [as well as in] the number of colours and figures”. It is interesting to note that the Observant Franciscans of Santa Maria della Pietà, la Fratta (now Umbertide) had made the same stipulation in respect of Pintoricchio’s altarpiece (1502-5) for the high altar of their church, and that Raphael seems to have been associated with its design (see above).

-

✴It referred to Raphael as “Maestro”, and specified that he would personally paint the figures.

-

✴It provided for the cost of transport of the main panel to Perugia, so it was clearly intended that Raphael would paint it somewhere else: the terms of the contract applied in Perugia, Assisi, Gubbio, Rome, Siena, Florence Urbino and Venice. It seems that Berto’s role would relate to:

-

•the co-ordination of the project as a whole; and

-

•the painting of the subsidiary panels in Perugia.

Contract of 1516

No subsequent documents referring to this commission survive until 1516, when the nuns sent Berto di Giovanni to Rome, presumably to press Raphael to begin work, and the contract was duly renegotiated. It was witnessed by Alfano di Diamante, the nephew of Sister Battista and probably the commissioner of Raphael’s so-called Connestabile Madonna (see above), and now specified only a year before delivery. This contract made a specific division between the work expected of the two artists:

-

✴Raphael would paint the main panel in Rome; and

-

✴Berto would paint, in Perugia, the frame and three predella panels, which would depict:

-

•the birth of the Virgin;

-

•the marriage of the Virgin; and

-

•the death of the Virgin.

This contract referred to a design by Raphael that had clearly been sent to the nuns in preparation for the contract negotiations. This suggests that the nuns had agreed to move away from the Narni altarpiece as a strict basis for the composition. The design that they accepted has been unfortunately been lost. It has been suggested that a drawing of the Dormition and Coronation of the Virgin in the British Museum, which is attributed to Giovanni Francesco Penni (see below), could be a copy of it. However, it seems odd that the nuns would have accepted this design while still requiring a scene of the death of the Virgin in the predella. In fact, the lower part of the drawing relates quite closely to the scene that was finally painted in the predella, albeit that it is reversed.

Berto di Giovanni provided a carpenter in 1518 to make the frame of the altarpiece and a "cassa” (probably a cover that protected it when it was not in use). However, the altarpiece had yet to be started when Raphael died in 1520.

Contract of 1523

In 1523, the nuns agreed a new contract for the main panel with two of Raphael’s associates in Rome: Giulio Romano and Giovanni Francesco Penni. Mariano di Ser Austerio acted on behalf of these artists in relation to payments made under this contract. Finally, on 25th June 1525, the “Memoriale di Santa Maria di Monteluce” records that “the Madonna, our finished painting, was delivered from Rome!”

-

✴the upper panel, which depicts the Coronation of the Virgin, is attributed to Giulio Romano; and

-

✴the lower part, which depicts the Apostles gathered around the Virgin’s empty tomb, is attributed to Giovanni Francesco Penni.

John Shearman (referenced below) has produced a hypothesis that would account for the composite nature of the finished work, suggesting that:

-

✴Agostino Chigi had commissioned an altarpiece of the Assumption of the Virgin for his family chapel in Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome;

-

✴Giovanni Francesco Penni executed the commission after Raphael’s death but Chigi refused to accept it; and

-

✴its lower part was reused for the panel sent to Perugia.

The lower part of the composition makes narrative sense in the context of the subjects painted in the predella, since it follows from the scene of the death of the Virgin. It is clearly not based on the lower part of the Narni altarpiece, but it is close to the lower part of Raphael’s Oddi Altarpiece (above). This suggests that the main panel did indeed follow a now-lost design by Raphael.

The frame for the altarpiece had been delivered to Berto di Giovanni for painting in 1524. He presumably began the three predella panels at this time. He also agreed to add a fourth predella panel, depicting the Presentation of the Virgin, as well of panels of SS Francis and Clare for the pilasters of the frame. This work was presumably completed in 1525, the date inscribed on predella panel of the birth of the Virgin. The finished altarpiece was probably in place on the high altar of Santa Maria di Monteluce in time for the Feast of the Assumption.

The altarpiece was dismantled in 1750, when the main panel was installed in a new frame on the back wall of the tribune and the other panels were removed to the sacristy. The original frame was presumably destroyed. The surviving panels were never reunited:

-

✴The main panel was one of three works of art in Perugia that were earmarked by the French for confiscation under the Treaty of Tolentino (1797). It was the subject of an important restoration in Paris in 1801. Antonio Canova recovered it in 1815, when it was secured for the Pinacoteca Vaticana. In return, Pope Leo XII gave the nuns a sum of money and the copy of the panel that can still be seen in the apse of the church.

-

✴The other panels were taken to Rome in 1812.

-

•Two of them (those depicting SS Francis and Clare) were subsequently lost.

-

•The four predella panels were returned to the church in 1817 and moved to the Galleria Nazionale in 1863.

Baglioni Altarpiece (1507)

A lost inscription apparently recorded that Atalanta Baglioni commissioned this altarpiece, which is signed by Raphael and dated by inscription. Giorgio Vasari reported that Raphael made the cartoon in Florence and then returned to Perugia to paint the altarpiece in Atalanta's chapel, the Cappella di San Matteo, in San Francesco al Prato. The commission was probably made in ca. 1505, and Raphael seems to have returned to Perugia from Florence in 1507 in order to deliver it. Domenico Alfani was associated in some way with the commission: a note that Raphael addressed to him on the back of a sketch (ca. 1507) of the Holy Family that is now in the Palais des Beaux Arts, Lille asks him (among other things) to obtain payment on his behalf from Atalanta Baglioni

Main panel

-

✴the body of Christ, which is laid on a sheet, is carried by two men, one of which (at the centre of the composition) almost certainly represented Atalanta's disgraced son, Grifonetto Baglioni, who had been murdered in 1500;

-

✴St John the Evangelist and a fourth man stand near the head of Christ;

-

✴St Mary Magdalene holds His hand; and

-

✴the Virgin, attended by three women, swoons at His feet.

The place of execution is on the hill to the right, and the tomb is in the rocks to the left. The panel is signed and dated on the stepping-stone to the bottom left-hand corner.

The Franciscans somewhat controversially sold this panel to Cardinal Scipione Borghese in 1608, having moved it first to the sacristy because the Cappella di San Matteo was subsiding. The French took it from Rome to Paris in 1797, but it was subsequently returned to the Galleria Borghese, Rome.

Cardinal Borghese promised to send a copy to Perugia, and made a payment to Giovanni Lanfranco for the work. However, the copy that he actually sent to Perugia in 1609 (along with five silver lamps by way of additional compensation) is attributed to Giuseppe Cesari, il Cavalier d’ Arpino. It is now in the Galleria Nazionale.

Upper Panel

-

✴Some scholars believe it to be the original, and suggest that it is a workshop production (sometimes attributed to Domenico Alfani) from a design by Raphael. (A possible design, which is attributed to Raphael, survives in the Palais des Beaux Arts, Lille).

-

✴Other scholars (and the gallery notes) suggest that this panel is a copy (ca. 1608) of the original and attribute it to Stefano Amadei. If it is indeed a copy, the original has been lost.

The panel depicts the figure of God the Father, who would have looked down across the intervening frame into the face of His dead Son.

Predella

The grisaille predella panels, which depict personifications of Hope, Charity and Faith in tondi, with putti between them, remained in the sacristy in 1608. The frame of the altarpiece was recorded in 1784 in the crossing of San Francesco al Prato, at which time it contained copies of the main and upper panels, with the original predella panels below. Napoleon's commissioner, Jacques-Pierre Tinet selected the predella panels for confiscation in 1797. Antonio Canova recovered them in 1815, when they were secured for the Pinacoteca Vaticana. They are illustrated in the Vatican website.

Copy of the Main Panel (16th century)

This panel on the right wall of the Oratorio di San Bernardino, which is attributed to Orazio Alfani, is the earliest known copy of the main panel of the Baglioni Altarpiece. It was first recorded in the sacristy of Sant' Agostino in 1863, the date at which it was transferred to the Galleria Nazionale. It was restored in 1970 and moved to its current location.

Read more:

The literature on Raphael is vast, but here are some of the works that I have used above:

T. Henry and F. F. Mancini (Eds), “Gli Esordi di Raffaello: tra Urbino, Città di Castello e Perugia”, (2006) Città di Castello.

C. Galassi, “Napoleonic Requisitions and the Myth of Raphael: Notes on the Removal of the Città di Castello Betrothal of the Virgin”, at pp 103-14 in the book referenced above

L. Wolk-Simon, “Raphael at the Metropolitan: the Colonna Altarpiece”, (2006), New York

H. Chapman et al. (eds), “Raphael: From Urbino to Rome”, (2004) London,

which is the catalogue of the brilliant exhibition that was held at the National Gallery, London

T. Henry,”Raphael’s Siege of Perugia”, Burlington Magazine, 146 (2004) 745-8

F. Mancini, “Raffaello in Umbria: Cronologia e Committenza: Nuovi Studi e Documenti”, (1987), Perugia

J. Shearman, "The Chigi Chapel in S. Maria del Popolo," Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 24 (1961) 129-60

U. Gnoli, “Raffaello e la Incoronazione di Monteluce”, Bollettino d' Arte, 11 (1917) 133-54

Return to Art in: Città di Castello Foligno Perugia.

Return to “Foreign” Painters in Umbria.