Detail of the fresco of miracle of the resurrected boy

Cappella di San Martino, Lower Church of San Francesco, Assisi

Giorgio Vasari reproduced a memorial inscription of “Simoni Memmio Pictorum”, which was apparently in Siena and which recorded that the deceased had lived for 60 years: since he certainly died at Avignon in 1344, it is usually assumed that he was born in 1284. His earliest known work is the Maestà in the Sala del Consiglio of the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena, which bears the name of the artist, “Symone” and the date 1315, and was the subject of regular payments until December of that year.

The Sala del Consiglio was probably built in 1304-10, and its subsequent decoration was designed to underline the adherence of Siena to the Guelf cause. To this end, the arms on the canopy over the Madonna and Child in the Maestà are those of Siena and of the kingdoms of France and Naples. Diana Norman (referenced below) has associated this with actual canopies that were commissioned for ceremonial entries into Siena by:

-

✴King Robert of Naples, in 1310, as he returned to Naples after his coronation in Avignon;

-

✴Count Peter of Eboli, the young brother of King Robert, in 1314, as he took up his appointment as commander of the forces of the Guelf League, which had been formed to oppose Uguccione della Faggiola, the Ghibelline ruler of Pisa; and

-

✴Prince Philip of Taranto, another brother of King Robert, in July 1315, as he replaced Peter of Eboli as commander of the forces of the Guelf League. (Philip was to return to Siena for two weeks after the disastrous defeat of the Guelfs at the Battle of Montecatini (1315), in which his brother Peter and son Charles both died).

By the time that Simone painted the Maestà, he was about 30 years old, but the work that must have pre-dated this important commission is unknown. His other surviving signed works before his departure for Avignon (see below) are as listed below:

-

✴The altarpiece of St Louis of Toulouse, which was almost certainly commissioned by King Robert (the brother of St Louis) at about the time of the canonisation (i.e. in ca. 1317), is now in the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. A payment recorded in Naples a few months after the canonisation to Simone Martin, “milite” (knight) is has been associated wit this commission, although other scholars have pointed out that:

-

•the reason for the payment is not specifically recorded; and

-

•Simone is not recorded in any surviving source as having been knighted.

-

✴The Pisa Polyptych (1319) from Santa Caterina,Pisa is now in the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo, Pisa.

-

✴The polyptych (ca. 1321) from San Domenico, Orvieto is described below.

-

✴The commemorative equestrian portrait (1328 or perhaps 1333) of Guidoriccio da Fogliano is in the Palazzo Pubblico, Siena.

-

✴The Annunciation (1333) for the Cappella di Sant' Ansano of the Duomo, Siena, which he signed with his brother-in-law Lippo Memmi, is now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Avignon

Simone moved to Avignon, probably in 1336, and he stayed there until his death in 1344. He met Petrarch there and they seem to have become close friends: in his copy of Pliny’s Natural History, alongside the description of the Greek artist, Apelles as “ a person of great amenity of manners”, Petrarch wrote “so it was with our Sienese Symoni”. Simone painted at least two works for Petrarch:

-

✴a now-lost portrait of the famous Laura, which is recorded in two of Petrarch’s sonnets:

-

•“But certainly my Simon was in Paradise, whence comes this noble lady; there he saw her and portrayed her on paper, to attest down here to her lovely face ...” (Canzoniere 77); and

-

•“When Simon received the high idea which, for my sake, put his hand to his stylus, if he had given to his noble work voice and intellect along with form, he would have lightened my breast of many sighs” (Rima estravagante 5 ); and

-

✴a painting on the title page of Petrarch's copy of the Works of Virgil, which is now in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan. A faint inscription below the picture translates: “Mantua gave birth to Virgil, who wrote these verses. Siena gave birth to Simone, who painted this figure”. This book had been stolen in 1326 but returned to Petrarch in 1338: the painting must have been executed between this date and Simone’s death in 1344.

Four other works are recorded from this period:

-

✴A panel of Christ returning to his parents after the dispute with the Doctors in the Temple, which was originally part a diptych, is signed “SYMON DE SENIS ME PINXIT SUB A. D. MCCCXLII” (1342). Nothing is known about its history prior to its sale in England in 1804. It is now in the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

-

✴A now-vanished inscription (was probably added in the 16th century) attributed the frescoes of the west porch of the Cathédrale Notre-Dame des Doms, Avignon to Simone. The arms on them suggest that Cardinal Jacopo Stefaneschi had commissioned them. If so, they must have been complete by 1341, when Cardinal Stefaneschi died, or shortly thereafter.

-

✴An inscription by Petrarch on a now-lost portrait of Cardinal Napoleone Orsini recorded that Simone had painted the portrait and given it to his doctor, John of Arezzzo so that he could use it to commend himself to Pope Clement VI. This portrait must have been painted in Avignon before the death of Cardinal Orsini there in 1342.

-

✴Two panels of scenes from the Passion that are signed "Pinxit Symon " belonged to the so-called Orsini Polyptych, was probably painted for Cardinal Napoleone Orsini in ca. 1340 (see below).

Orsini Polyptych and St Clare of Montefalco

This polyptych was a small, devotional work made up of four double-sided panels that were hinged like a concertina.

-

✴When it was closed, the two visible surfaces displayed the Orsini arms.

-

✴When it was partly open, the visible scenes depicted the figures of the Annunciation;

-

✴When it was fully open, it depicted four scenes from the Passion of Christ:

-

•the way to Calvary;

-

•the Crucifixion;

-

•the deposition of Christ from the cross; and

-

•the entombment of Christ.

The polyptych seems to have been in the charterhouse of Champmol, near Dijon, by the the late 14th century, and the panels were subsequently dispersed:

-

✴the panels of the Annunciation, and those of the Crucifixion and the deposition of Christ, which were behind them, are now in the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp;

-

✴the way to Calvary is now Musée du Louvre, Paris; and

-

✴the entombment of Christ (now in the Staatliche Museen, Berlin).

Joel Brink (see the reference below) has pointed to a number of factors that suggest that Simone painted it for Cardinal Napoleone Orsini at Avignon, and that it reflected his devotion to the Passion of Christ and to the cult of St Clare of Montefalco. (As Papal Legate to Umbria, Cardinal Orsini had initiated the process for the canonisation of St Clare in 1308, but this had been suspended in 1333).

Assisi

The historical context of the frescoes described here is set out in the page on San Francesco in the 14th century).

Cappella di San Martino (ca. 1316-7)

The frescoes of the Cappella di San Martino in the Lower Church of San Francesco, which depict scenes from the life of St Martin of Tours, were first attributed to Simone Martini in 1820, and this is now widely accepted. The patron of this chapel was the Franciscan Gentile Partino da Montefiore, Cardinal Priest of San Martino ai Monti in Rome (pictured above, kneeling before St Martin), who paid 600 gold florins for the purpose while he was in Assisi on papal business in 1312. He then stopped at Siena (en route for Avignon) and he might have seen works by Simone there that no longer survive. He died at Lucca shortly thereafter and his body was taken to Assisi. “His” Cappella di San Martino seems to have been incomplete at this date, so he was buried in another chapel in the Lower Church. The frescoes in the Cappella di San Martino must thus have been commissioned by his (unknown) executors. Stylistic considerations suggest that they post-date the Maestà, it it seems likely that work began on them in 1316.

The stained glass in three large two-light windows of the chapel is attributed to Giovanni di Bonino, in association with Simone Martini.

Altare di Sant’ Elisabetta (ca. 1317)

This fresco above what was once the Altare di Sant’ Elisabetta in the right transept of the Lower Church of San Francesco is also attributed to Simone Martini.

-

✴The fresco on the right wall, which was originally over the altar, depicts the Madonna and Child flanked by two royal saints. TThese are probably the great royal saints of Hungary:

-

•St Stephen, the first Árpád king; and

-

•St Ladislas.

-

✴The frieze on the back wall depicts five more saints:

-

•St Francis (far left);

-

•St Louis of Toulouse, who rests his renounced crown of Naples on the fictive frame around the fresco;

-

•St Elizabeth of Hungary, who points to the Madonna and Child on the right wall; and

-

•two saints with unfinished crowns above their respective haloes:

-

-a female saint who is probably St Agnes of Bohemia or St Margaret of Hungary; and

-

-a male saint is who probably St Henry (Emeric), the son of St Stephen.

The presence of St Louis of Toulouse suggest that these frescoes, like those on the arch of the Cappella di San Martino, were commissioned to celebrate his canonisation in 1317. The presence of a number of the saints of the Árpád dynasty (i.e. SS Elizabeth, Stephen, Ladislas and Henry) suggest the influence of Queen Maria, who was the mother of St Louis and an Árpád princess (a great niece of St Elizabeth). She may well have commissioned the frescoes soon after the canonisation of St Louis in 1317. Another participant might have been Charles Robert, the grandson of Queen Maria, who had won the crown of Hungary in 1310 after the intervention of Cardinal Gentile:

-

✴Charles Robert is known to have sent gifts to San Francesco with Cardinal Gentile in 1312;

-

✴the frescoes underscored his status as the legitimate successor of the saintly Árpád kings of Hungary, with whose regalia he had recently been endowed; and

-

✴they also commemorated his uncle, St Louis, to whose cult he was devoted.

Orvieto

Panels from the San Domenico Polyptych (ca. 1321)

These five panels in the Museo dell' Opera del Duomo are the only ones that survive from a polyptych from San Domenico, Orvieto. The central panel bears the signature of Simone Martini and the date MCCCXX... (1320 or soon thereafter). The polyptych also probably had panels in an upper register and a predella below, but these have been lost.

The gallery displays the surviving panels thus:

-

✴SS Mary Magdalene, Dominic and Peter on the left; and

-

✴St Paul on the right.

If (as seems likely) this is their original disposition, there must have been two other panels in this register depicting saints (probably of SS Peter Martyr and Catherine of Alexandria, to the sides of St Paul) looking to the left. The lovely figures of SS Peter and Paul are markedly more lifelike than the others, which have suffered from over-restoration and may in any case have been workshop productions.

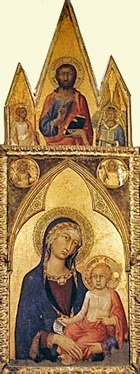

Panel from San Francesco Polyptych (ca. 1325)

-

✴The scene in the pinnacle depicts Christ the Redeemer, with one hand raised in blessing and the other holding a closed book. Each of the smaller gabled fields to the side contains an angel. Inscriptions below identify Christ as ALPH- & O (Alpha and Omega) and the angels, respectively as ..RAP-YM (Seraphim) and CERUB-M (Cherubim).

-

✴The main part of the panel below depicts the Madonna and Child. The angels in the tondi in the spandrels are identified as TRONE (Thrones).

The types of angels depicted here (Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones) form the highest order of the hierarchy of angels. It is likely that angels depicted in the lost panels were also taken from the defined orders of angels.

This panel almost certainly came from a polyptych, but the other components have been lost. A panel of St Catherine of Alexandria that is now in the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa is thought to have been among them.

Gardner Polyptych (1320s)

These five panels in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, , Boston, Massachusetts, which are attributed to Simone Martini, were first documented in 1671, when they were in the sacristy of Santa Maria dei Servi, Orvieto. They probably came from a polyptych that was installed on the high altar there. These surviving panels depict:

-

✴the Madonna and Child with Christ the Redeemer above;

-

✴St Paul;

-

✴St Lucy;

-

✴St Catherine of Alexandria; and

-

✴St John the Baptist.

Each panel has a musical angel above carrying an instrument of the Passion. These were probably the only main panels of the polyptych, but it almost certainly also had predella panels that have been lost.

The later history of the surviving panels was described in a series of letters that were discovered in Rome in the 1980s. The Servites seem to have sold them in ca. 1842 to two Chilean diplomats, probably to raise money following the collapse of their church. The sale came to light when the Chileans attempted to export the panels, and the Roman authorities insisted that it should be returned to Santa Maria dei Servi. In 1851, the friars finally received permission to sell them to Leandro Mazzocchi on the condition that they should be installed in his private chapel in Orvieto. In fact, the Mazzocchi family lent them to the Museo dell' Opera del Duomo and then sold them to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in 1899.

References:

D. Norman, “ ‘Sotto uno Baldachino Trionfale’: the Ritual Significance of the Painted Canopy in Simone Martini’s Maestà”, Renaissance Studies, 20 (2006) 147-60

A. Martindale, “Simone Martini: Complete Edition” Oxford (1988)

J. Brink, “Cardinal Napoleone Orsini and Chiara della Croce”, Zeitschrift fűr Kunstgeschichte, 46 (1983) 419-24

Return to Art in: Assisi Orvieto.

Return to “Foreign” Painters in Umbria.