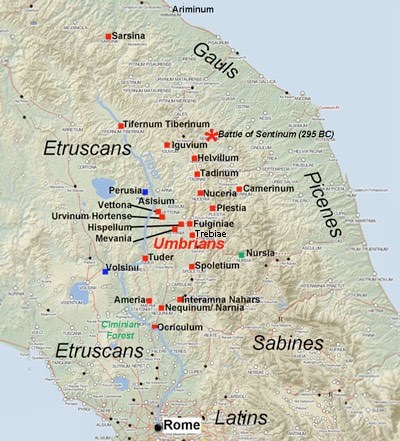

Red dot = Umbrian city;

Blue dot (Volsinii and Perusia) = neighbouring Etruscan city

Green dot (Nursia) = neighbouring Sabine city

Adapted from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire

The Umbrians

At the dawn of history, an ancient people that the Romans later knew as the Umbrians occupied much of central Italy. The Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus, whose ‘Roman Antiquities’ was published in Rome in 7 BC, recorded that these people (whom he called by their Greek name, the ‘Ombrici’) originally inhabited much of central Italy and:

-

“... were a great and ancient people”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 19: 1).

Almost a century later, Pliny the Elder went further:

-

“The Umbrians are said to be gens antiquissima Italiae (the most ancient people of Italy), and are thought to have been designated as Ombrii by the Greeks on account of their having survived the rains after the flood", ‘Natural History’, 3: 19).

By the time of the foundation of Rome (traditionally 753 BC) the Umbrian heartland had probably stabilised in and areas between the Tiber Valley and the Apennines . They shared a language that, at least from the 5th century BC, was written using an Etruscan alphabet (as evidenced by surviving inscriptions). Although we can appreciate many aspects of their culture from the surviving archeological and epigraphic record, we are reliant on Greek and Roman historians for our knowledge (such as it is) of their history.

It was, of course, the Romans. who brought an end to this Umbrian culture, as evidenced by the fact that the ancient cities in the region are almost invariably known by their Latin names (as in the map above). The Romans first expanded across the Tiber into southern Etruria after the fall of Veii in 396 BC. They famously crossed the Ciminian Forest and began their conquest of northern Etruria and Umbria in 310/9 BC, and their decisive victory over an alliance of Samnites, Gauls, Etruscans and Umbrians in the territory of Sentinum in 295 BC marked the beginning of the end of Umbrian independence. The process of their absorption into the Roman world can be traced in the epigraphic record of the region, in which the Latin alphabet and then the Latin language took hold in the 2nd century BC.

Umbrian Peoples

Greek and Roman historians generally referred to the ancient Umbrians without differentiating between them. Thus, for example, Cicero, in a book on the ancient art of divination (ca. 44 BC), noted that:

-

•“... the people of Etruria are very skilful in observing thunderbolts and in interpreting their meaning and that of every sign and portent. ... [Other peoples] rely chiefly on the signs conveyed by the flights of birds ... [For example], according to tradition, this used to be the case in Umbria”, (‘De Divinatione’, 1: 92: 42); and

-

•“... I believe that the character of the country determined the kind of divination that its inhabitants adopted. ... [For example, those peoples that were] chiefly engaged in the rearing of cattle, and were therefore constantly wandering over the plains and mountains in all seasons, found it quite easy to study the songs and flights of birds. This is true ... [inter alia] of nostrae Umbriae (our fellow-countrymen, the Umbrians)”, (‘De Divinatione’, 1: 93 (43).

Similarly, in his slightly later account of the history of the Italy, Dionysius recorded that, in 524 BC, the Etruscans:

-

“ … joined with the Umbrians, Daunians and many other barbarians [against] Cumae [which was then a city of Greek-speakers south of Rome] ...”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 7: 3); and

It is most unlikely that all of the Umbrian (or, indeed, all of the Etruscans) had been involved in this engagement. However, while Dionysius recognised that the Umbrians were ethnically distinct from their Etruscan neighbours (not least because their respective languages were completely unrelated to each other), his sources did not know (or did not think it important to record) which Umbrians and which Etruscans had been involved. Dionysius’ contemporary, Livy, mentioned the Umbrians for the first time, in the context of the events of 310/9 BC (mentioned above): he observed that the people living north of the Ciminian Forest had suffered the hostile attentions of a Roman army for the first time, and that:

-

“... this had aroused the resentment, not only of Etruria, but also of the neighbouring parts of Umbria”, (‘History of Rome’, 9: 37: 1).

Here, the Umbrians in question were only those living below the forest (presumably those of Ocriculum, Ameria and Nequinum). However, either Livy or his sources could not (or did not feel the need to) identify them by name

We know that the ethnic designation ‘Umbrian’ was in use at an early date: as discussed in my page on Early Italic Inscriptions, there is epigraphic evidence for this from:

-

✴two Greek inscriptions (6th century BC) from Etruria; and, more importantly

-

✴in two inscriptions in an Italic language known as South Picene (which was related to Umbrian and spoken along the Adriatic coast), one from the 5th and one from the 3rd century BC.

However, while surviving Umbrian inscriptions of the 4th century BC record:

-

✴cupras, matres pletinas , which refers to the goddess Cupra as the mother of the Umbrians of what became Roman Plestia; and

-

✴totar tarsinater trifor tarsinater” (the Tadinate community, the Tadinate territory), which refers to the Umbrians of what became Roman Tadinum;

we have no epigraphic evidence of any kind that any of ‘the Umbrians’ ever used this collective designation to describe themselves or their homeland (although this could, of course, be an accident of survival).

It is unlikely that the Plestini and the Tadinates (for example) had anything approaching a city in the 4th century BC. However, Umbrian society was slowly urbanised thereafter, and we can now recognise a number of we might reasonably regard as pre-Roman ‘Umbrian’ centres of population. We know the Umbrian names for some but not all of them (and they are all conventionally identified by their Roman names). Those for which we have a significant amount of archeological, literary (meaning, of course, Greek or Roman) and/or epigraphic evidence (marked with red dots in the map above) are:

-

✴Ameria (modern Amelia);

-

✴Asisium (Assisi);

-

✴Fulginiae (Foligno);

-

✴Hispellum (Spello);

-

✴Iguvium (Gubbio);

-

✴Mevania (Bevagna);

-

✴Nequinum, later Narnia (Narni);

-

✴Nuceria (Nocera Umbra);

-

✴Ocriculum (Otricoli);

-

✴Spoletium (Spoleto);

-

✴Tadinum (Gualdo Tadino);

-

✴Tifernum Tiberinum (Città di Castello);

-

✴Tuder (Todi); and

-

✴Vettona (Bettona).

According to Pliny the Elder, when the Emperor Augustus reorganised the administrative structure of peninsular Italy in 7 BC, all of these were included in the Sixth Region, ‘Umbria and the Gallic territory’ (‘Natural History’, 3:19), which was separated from the Seventh Region, ‘Etruria’, by the Tiber. Of course, Italy was thoroughly Romanised by this point, and the regions were based on geography, albeit with a ‘nod’ to ancient ethnicity. It seems that the Tiber Valley was a permeable border in ancient times and, in particular (as we shall see), that the ‘Umbrian’ centres of Tuder, Vettona and Tifernum Tiberinum were open to Etruscan cultural influence. More generally, Guy Bradley (referenced below, at p. 100) argued that the proximity of the:

-

“... powerful and sophisticated [Etruscan cities of Perusia and Volsinii] helps to explain the heavily ‘Etruscanised’ nature of Umbrian culture in the pre-conquest (and, indeed, in the post-conquest) era.”

Return to Key to Umbria: History