Temple from a relief from the Tomb of the Haterii

Museo Gregoriano Profano, Musei Vaticani, Rome

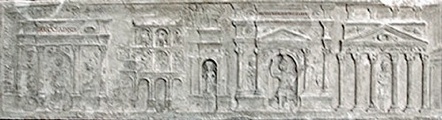

In this page, I discuss the suggestions that have been made for the identity of the temple that was depicted in the relief above, which came from the Tomb of the Haterii. It was depicted on a longer relief (illustrated below) that depicted five monuments. This, in turn, wasone of three reliefs from the tomb that are preserved in the the Museo Gregoriano Profano, Musei Vaticani.

My conclusion is that the temple depicted on the long relief was the Temple of Jupiter Stator, which was rebuilt in this form after the fire of 64 AD. I then look at the suggestions that have been put forward for the location of this temple, and conclude that it probably stood at the top of the Sacra Via, either on the later site of the Maxentian basilica nova or perhaps opposite it.

The history of this temple has long been a matter of intense debate among scholars. I have done my best below to summarise the main lines of argument and come to a conclusion. However, please do not rely on it: read it critically, check the original sources and reach your own conclusion.

Tomb of the Haterii

The so-called Tomb of the Haterii was discovered on the Via Labicana (outside Rome) in 1848 and further excavated in 1970. An inscription found at the site (CIL VI 19148), which is now also in the Museo Gregorio Profano, identifies its owners as members of a family of freedmen of the Haterius family.

According the Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, 2009, p. 429):

-

“It is proposed that the owner of the tomb was [the freedman Quintus] Haterius Tychicus, who is known from a lost inscription (CIL IV 607) ... [in which he] declared his profession of ‘redemptor’ (a businessman involved with public contracts). In that case, we can interpret the presence of ... the Roman edifices in the [long relief] as testimony of works in which the owner of the tomb had participated” (my translation).

Lynne Lancaster (referenced below, at p. 19) was more cautious:

-

“[Quintus Haterius Tychicus] may be the same person who was buried in the tomb of the Haterii. Unfortunately, the cognomen of the deceased in the tomb is not preserved [in CIL VI 19148, above, so we cannot] verify his association with Tychicus. Nevertheless, the iconography of the reliefs in the tomb suggests that the deceased may have been involved in the building trade, as was another freedman of the Haterius family, [Quintus] Haterius Evagogus [described in CIL VI 9408 as an official of the carpenters’ guild].”

Another of these three reliefs (illustrated here) famously depicted the tomb itself, during its construction, with slaves operating a crane of some sort to the left. I have to say that the presence this relief makes Quintus Haterius Tychicus a better candidate for the man whose architectural achievements are probably celebrated in the ‘long relief’ than the carpenter Quintus Haterius Evagogus.

Relief of Five Flavian Monuments

Temple from a relief from the Tomb of the Haterii

Museo Gregoriano Profano, Musei Vaticani, Rome

The long relief depicts (from the left):

-

✴an arch with the inscription ‘Arcus ad Isis’, which was presumably close to the Temple of Isis and Serapis in the Campus Martius;

-

✴the Flavian amphitheatre, now known as the Colosseum (minus its later upper storey);

-

✴a monumental triumphal arch;

-

✴an arch with the inscription ‘Arcus in Sacra Via summa’; and

-

✴the temple under discussion here, which is a hexastyle temple to Jupiter (as evidenced by its cult statue).

Filippo Coarelli (as above) described the fragmentary structure at to the right of this temple as:

-

“... a two-storey portico, [depicted] in perspective” (my translation).

The amphitheatre in the relief is definitely a Flavian monument, and it seems likely that the other monuments also date to this period (i.e. 69-96 AD). Filippo Coarelli (as above) observed that the relief had probably been reversed and reused in another context and suggested that this was:

-

“... the consequence of the death and damnatio memoriae of Domitian [in 96 AD], for whom Haterius had certainly worked” (my translation).

Temple of Jupiter

Jupiter Tonans ?

Lawrence Richardson (referenced below, at p. 226) described details of the temple in the long relief that are relevant to its identification:

-

“The frieze is decorated with sacrificial implements and eagles, and the pediment with a large wreath. The cult statue is shown frontal, emerging at the knees from a rock or pile of rocks. It probably had a sceptre in the left hand (it is hidden) and cradles a thunderbolt in the right. Above the temple, a curious attic storey ... is added, the purpose of which is very obscure: it has short, unfluted pillars with ionic capitals and a flat roof, evidently projecting, and the parapet is decorated with large thunderbolts”.

Richardson tentatively suggested that this represented the Temple of Jupiter Tonans (the Thunderer) on the Capitol, following a suggestion by Ernest Nash (referenced below, at 1.535).

Augustus originally vowed this temple in 26 BC, after a narrow escape from a lightning strike, and it was dedicated 1st September, 22 BC. It was among the temples that he recorded in the ‘Res Gestae Divi Augusti’: IV.5. Suetonius recorded an anecdote that helps to locate it more precisely:

-

“Being in the habit of making constant visits to the temple of Jupiter the Thunderer, which he had founded on the Capitol, [Augustus] dreamed that Jupiter Capitolinus complained that his worshippers were being taken from him. [Augustus] answered that he had placed the Thunderer hard by [theTemple of Jupiter Capitolinus] to be his doorkeeper; and accordingly he presently festooned the gable of the temple with bells, because these commonly hung at house-door” (‘Life of Augustus’, 91:2)

This suggests that the temple stood quite close to the entrance to the Capitol, and therefore on the south-east edge of the hill overlooking the Forum.

Augustus depicted this temple (identified by inscription) on the reverses of seven coins issued in 19 BC. It is shown as hexastyle (although other columns might have been ‘removed’ to reveal the cult statue), with a three-stepped crepis (base). According to Pliny the Elder, the cult statue had been the work of the Greek sculptor Leochares (4th century BC):

-

“Leochares made ... a figure ... of Jupiter Tonans in the Capitol, the most admired of all his works”, (‘Natural History’, 34:19).

As Paul Zanker (referenced below, at p. 240) observed:

-

“[Augustus’ choice of cult statues for his Temple of Apollo represented] the earliest reuse of Classical Greek originals in Rome. ... under Augustus, several other examples of this kind of reuse are known, such as the nude Zeus of Leochares in the Temple of Jupiter Tonans.”

This statue (which is well-illustrated in this description of RIC I (2nd edition) Augustus 63A) apparently depicted the standing Jupiter holding a thunderbolt in his right hand and a vertical spear or sceptre in his left.

Jupiter Stator ?

Filippo Coarelli (as above) described the cult figure of Jupiter depicted in the temple relief as:

-

“... apparently inserted up to the knees in a rough-hewed block that rests on a base (one cannot refer to an altar with flames, as is generally proposed)” (my translation).

and he suggested that:

-

“... the immobilisation in stone of the legs of the deity alludes to the defining immovability of Jupiter Stator’ (my translation).

He thus identified the temple as that of Jupiter Stator. Fabiola Fraioli (referenced below, at p. 295) agreed:

-

“On the Sacra Via, the Temple of Jupiter Stator was rebuilt after the fire of 64 AD and [then] mentioned in [the regionary catalogues of the ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’]. It is represented in a relief from [the Tomb of the Haterii], identifiable thanks to the cult statue at the centre of the edifice, which represents Jupiter with his legs embedded in a block of stone” (my translation).

Atilius Regulus had vowed a temple to Jupiter Stator during a battle against the Samnites in 294 AD (as described in my page on Victory Temples and the Third Samnite War). It is known from literary sources that this temple was built on the lower slopes of the Palatine, not far from the Forum. It was almost certainly destroyed in the fire of 64 AD, and certainly rebuilt thereafter: we have what seems to be an eye-witness record of the post-Neronian temple, in Plutarch’s account of Cicero’s first denunciation of Cataline in 63 BC, which was probably written after his (Plutarch’s) visit to Rome in 92 AD. In it, he recorded that:

-

“... Cicero went forth and summoned the Senate to the temple of [Jupiter Stator], situated at the beginning of the Sacra Via, as one goes up to the Palatine” (‘Life of Cicero’, 16:3).

(I have taken this from Adam Ziolkowski’s book, referenced below, 2004, p. 13). This temple was recorded as the aedes Iovis Statoris in regio IV (Templum Pacis) in the regionary catalogues in the ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’.

Jupiter Stator first appeared (identified by inscription) on the reverses of five coins (RIC III Antoninus Pius: 72A; 72B; 72C; 607a; and 607c in 141 AD that were issued during the 3rd Consulship of the Emperor Antoninus Pius. The catalogue describes their identical reverses as follows:

-

“IOVI STATORI: Jupiter, naked, standing [facing] front, holding sceptre in right hand and thunderbolt in left” (as illustrated here for RIC 607a).

My Conclusion

The feet of Jupiter were certainly not encased in stone in the ‘traditional’ images of either Jupiter Tonans or Jupiter Stator (at least as evidenced by the coin reverses above). Thus, it seems to me that the depiction of the temple on the relief does not include a representation of the actual cult statue in the temple. Rather, it depicts a fictive statue that was specifically intended as a clue to the temple’s identity. The attribute of a thunderbolt was certainly not unique to Jupiter Tonans, but was common in Jovian iconography. However, as Filippo Coarelli pointed out, the immobilisation of Jupiter in the relief would convey perfectly the identity of the temple: it seems to me that it must have represented the Temple of Jupiter Stator as it existed in the Flavian period.

Post-Neronian Temple of Jupiter Stator

As noted above, Plutarch, who was writing in ca. 92 AD, recorded that the Temple of Jupiter Stator was then:

-

“... situated at the beginning of the Sacra Via, as one goes up to the Palatine” (‘Life of Cicero’, 16:3).

Of course, Plutarch was referring to the Sacra Via after its redevelopment in the Neronian and Flavian periods: no pre-Neronian source had placed this temple on the Sacra Via, so it had clearly been rebuilt in this new location after the fire of 64 AD. Michele Salzman (referenced below, at p 127) listed the 13 festivals recorded in the so-called ‘Calendar of Philocalus’ in the ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’ that had been added to the Roman calendar after the mid 1st century AD. These included a festival involving 24 chariot races on 13th January:

IOVI·STATORI·CM·XXIIII;

which might record the dies natalis of this rebuilt temple (although it could alternatively relate to a later restoration or rebuilding and subsequent re-dedication).

In 1999, Adriano la Regina (referenced below) published a survey of the previous scholarship on the topography of Rome after the fire, in which he drew attention to a casual reference in a work by Galen, a Greek polymath who lived in Rome at the end of the 2nd century AD. In this treatise on medical practice, Galen advised surgeons experimenting on the arteries of animals to a use ligatures:

-

“... of a material that will not readily decompose. Such a material can be obtained in Rome from the Gaietans, who bring it from the country of the Celts and sell it in the Sacra Via, which leads from the Temple of [Venus and] Roma to the Forum” (‘Methodus medendi’, 13:10).

Cassius Dio had also placed the Temple of Venus and Roma on the Sacra Via:

-

“In the 6th consulship of Vespasian and the 4th of Titus [i.e. 75 AD], ... the ‘Colossus’ [huge statue that had been commissioned by Nero] was set up on the Sacra Via [only to be moved again to make way for the Temple of Venus and Roma]” (‘Roman History’, 65:15).

He later mentioned the Sacra Via in this new urban context: commenting on the Temple of Venus and Roma to its proud designer (none other than the Emperor Hadrian himself) the out-spoken (not-to-say foolhardy) Apollodorus, who was a professional architect, opined that:

-

“.... it ought to have been built on higher ground ... so that it might have stood out more conspicuously on the Sacra Via from its higher position” (‘Roman History’, 69:4).

Cassius Dio’s remarks had previously been held to be too ‘general’ to have been of use for precisely locating the new course of the Sacra Via. However, taken together with the remark of Galen, this was no longer the case. Thus, Adriano la Regina concluded (at p. 32) that:

-

“It is no longer possible to doubt that [after the redevelopment that followed the fire of 64 AD] the Sacra Via ran from the Forum to the Arch of Titus and that, from the time of Hadrian [and thus of the construction of his Temple of Venus and Roma], it ended there ...” (my translation).

This was not strictly accurate: the Arch of Titus was not on the Sacra Via (albeit that it was near the Temple of Venus and Roma). Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, 2012, at p. 478) was more accurate:

-

“... we must reaffirm that, on the basis of Galen’s text, the [redesigned] Sacra Via started at the Temple of Venus and Roma” (my translation).

Peter Wiseman (referenced below, 2013, at p. 246) elaborated on this point:

-

“After the fire, Nero’s architects redeveloped the whole area from the Forum up to the ridge where the Arch of Titus now stands, turning the old Sacra Via into a grand rectilinear avenue flanked with porticos, leading [from the Forum] up to the [vestibule of Nero’s] new imperial palace [later the site of the Temple of Venus and Roma].”

This, then, is the urban topography in which we must locate the rebuilt temple. If Plutarch had accurately located the rebuilt temple, it was at one or other end of this new Sacra Via:

-

✴near the later site of the Temple of Venus and Roma; or

-

✴near the Forum;

depending upon which he perceived to have been at its beginning (as opposed to its end).

Proposed Locations

Sacra Via after the fire of 64 AD

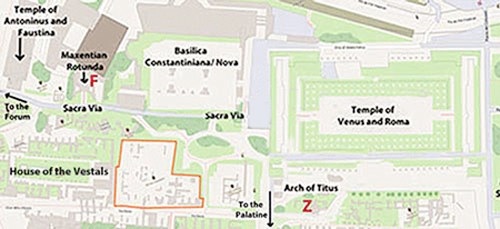

Traditional View (Adam Ziolkowski)

Adam Ziolkowski (referenced below, 2004, at 73) believed that Atilius’ temple was rebuilt after the fire of 64 AD on its original site, which he identified as that of a podium that has been excavated to the southeast of the Arch of Titus (marked ‘Z’ on the plan above). He

construed Plutarch’s phrase locating the rebuilt temple (above) as follows:

-

“... we learn from Plutarch that, in his day, ... the temple of Jupiter Stator stood by that end of the Sacra Via from which one went to the Palatine, or, in other words, at the point where the Sacra Via met the ‘Palatine street’.”

In fact, the podium in question was not on the Sacra Via but rather a little way south along this ‘Palatine street’. Ziolkowski appeared to acknowledge (at p. 74) that this implied a lack of precision on Plutarch’s part, but he suggested that this was of little significance:

-

“The location of the temple .... in Plutarch’s ‘Life of Cicero’, ... although slightly imprecise, renders its position [near the Arch of Titus] quite well ...”

Javier Arce and his colleagues (referenced below), who excavated the site of the podium in the 1980s, dated it to the Severan period (late 2nd century AD). Adam Ziolkowski (referenced below, 2004, at pp. 65-6) responded by making two points:

-

✴“The Severan date for the podium, [which is] based on pottery finds from one limited sounding, ... is anything but secure; ...”; and

-

✴“[In any case, a Severan date would not undermine the conventional view that the temple was rebuilt here after 64 AD, since,] in 191 AD, the area between the Templum Pacis and the Imperial palace on the Palatine was [once more] ravaged by fire, the traces of which have been found in the Horrea Vespasiani, immediately north west of the Arch of Titus”.

In other words, the temple could well have been rebuilt once more after this later fire. However, he noted (in his paper referenced below, 2015, at p. 579) that, since the podium:

-

“... fills the gap in the otherwise-continuous front of:

-

-the west façade of the Vigna Barberini on one side; and

-

-the Arch of Titus and the porticoes flanking the precinct of Venus and Roma on the other;

-

some building must have stood there from the time that [this continuous] front was created (i.e., since the Flavian regulation of the zone).”

Arce and his colleagues presented a more serious challenge to the traditional view when they doubted that the podium had ever supported a temple. Adam Ziolkowski therefore addressed their analysis of what the podium’s characteristics revealed about the building that it actually had supported. He argued (2004, at p. 68) that, contra Arce et al., this building:

-

“... could have been symmetrical only longitudinally [my italics].”

The excavators had uncovered a concrete core on the building’s long axis, which was markedly east of centre and had larger foundations than the rest of the structure. Ziolkowski agreed with their suggestion that it:

-

“... could well have supported a statue or some other memorial. Indeed, the core’s position ... is exactly in the right spot [for the cult statue] in a west-facing temple, [and there] are good reasons to believe that our monument actually faced west ...”.

He concluded that, notwithstanding the excavators’ contrary opinion, their data were consistent with:

-

“.... a Roman temple, symmetrical on the long axis, with the cella to the east and the porch to the west.”

Filippo Coarelli, who has long contested this view, reiterated his point in his recent book (referenced below, 2012, at p. 107), where he asserted that:

-

“...the building [on the podium] by the Arch of Titus cannot have been the Temple of Jupiter Stator, since it ... [was] probably an arcus quadrifrons [four-sided arch with an opening in each side], ... as shown by the excavations carried out by [Arce et al.].”

In his review of Coarelli’s book, Adam Ziolkowski (referenced below, 2015, at p. 578) countered by insisting that:

-

“... the podium, [which is] in the form of [a markedly] elongated rectangle and transversally asymmetrical (the typical layout of a Roman temple), could not belong to an arcus quadrifrons, [which would be] quadrangular and with two axes of symmetry: not to mention the absurdity that would be a free-standing arch leaning against an enormous façade [i.e. the west façade of the Vigna Barberini].”

My Assessment

It seems to me that (contra Adam Ziolkowski) the podium southeast of the Arch of Titus is inconsistent with Plutarch’s description of the temple’s location (it was not on the SacraVia), and that the case for it can be made only if one assumes that Plutarch was essentially mistaken (perhaps because he was writing of a location imperfectly remembered).

If Plutarch’s account is set aside, then the case for this location rests essentially on the archeological evidence. In his book of 2004, Adam Ziolkowski made a plausible case that, notwithstanding the doubts expressed by the excavators of the site, the podium had supported a west-facing Flavian temple, perhaps rebuilt after the fire of 191/2 AD. Filippo Coarelli’s recent attack on this view and Ziolkowski’s repost are summarised above. These are dangerous waters for a weak swimmer, but here goes: it seems to me that Adam Ziolkowski’s contention that the podium could have supported a Flavian temple, perhaps rebuilt in the Severan period, is a reasonable one.

The key question is: could this putative temple have been the rebuilt Temple of Jupiter Stator? Adam Ziolkowski’s contentions that it relies on two premises:

-

✴that the podium was on essentially the same site as Atilius’ earlier temple of Jupiter Stator; and

-

✴that this was the site of the aedes Iovis Statoris listed under regio IV in the regionary catalogues of the ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’.

As discussed in my page on Victory Temples and the Third Samnite War, it seems more likely that Atilius’ temple was closer to the Forum than this. However, it might have been rebuilt on here after the fire of 64 AD, provided one discounts Plutarch’s assertion that it was rebuilt on the Sacra Via. In short, everything depends on the interpretation of the entries in the regionary catalogues, and particularly on Adam Ziolkowski’s contention (discussed below) that this site on the Palatine was in regio IV (Templum Pacis) rather than in regio X (Palatium).

Suggestion of Peter Wiseman (2013)

When Peter Wiseman (referenced below, 2013, at p.246) construed the key passage from Plutarch’s ‘Life of Cicero’, he came to a conclusion that placed the Temple of Jupiter Stator at the opposite end of the Sacra Via from that proposed by Adam Ziolkowski (above):

-

“No pre-Neronian source describes the Sacra Via as leading to the Palatine; but now Palatium also meant ‘palace’, and that was where the new Sacra Via took you.”

In other words, according to this viewpoint, Plutarch had placed the temple near the Forum, at the beginning of the Sacra Via as one walked towards the vestibule of Nero’s palace (which was later the site of the Temple of Venus and Roma). (One would then turn right here, along Ziolkowski’s ‘Palatine street’, in order to climb the Palatine Hill).

Peter Wiseman (at p. 247) then pointed to a scenario that might have placed the rebuilt temple close to the Forum, which started with his view that Atilius’ temple had been built on a site later used for the House of the Vestals (marked on the plan above). He suggested that:

-

“Nero’s architects might well have rebuilt [this temple] directly across the street, at the beginning of the new Sacra Via as you went up to the Palatium [i.e in the location that Plutarch described]...”

Wiseman’s view that the temple’s new site had to be across the street from its original location on the lower slopes of the Palatine is explained by his observation (at p. 245) that:

-

“Surprisingly, the [regionary catalogues in the ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’] place the [rebuilt] temple not in regio X (Palatium) but in regio IV (Templum Pacis), and therefore north of the Sacra Via, which formed the boundary [my italics]”.

In fact, as discussed below, some scholars place this boundary slightly further south, which (if correct) would additionally permit the rebuilt temple to be sited on the south side of the Sacra Via.

My Assessment

I think that, in 92 AD, ‘the palace’ would have meant Domitian’s palace (rather than Nero’s palace), which was reached by Adam Ziolkowski’s ‘Palatine street’. In other words, the palace and the top of the hill were in the same place. If so, Adam Ziolkowski’s interpretation (above, repeated here with my addition in square brackets and italics) could still apply:

-

“... we learn from Plutarch that, in his day, ... the temple of Jupiter Stator stood by that end of the Sacra Via from which one went to the Palatine, or, in other words, at the point where the Sacra Via met the ‘Palatine street’ [which led to Domitian’s palace at the top of the hill].”

Thus, as discussed below, I think that we are looking for a site at the other end of the Sacra Via, near the Temple of Venus and Rome.

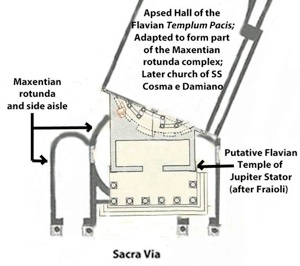

View of Fabiola Fraioli (2012)

Flavian Temple of Jupiter Stator proposed by Fabiola Fraioli

Mapped onto a plan of the later structures on the site

Fabiola Fraioli (referenced below) believed that Atilius’ temple had been rebuilt after the fire of 64 AD on its original site, which she identified as the later site of the Maxentian rotunda on the north side of the Sacra Via (marked ‘F’ on the plan above). She asserted (at p. 295 and Tables 100a and 104) that:

-

“On the Sacra Via, the Temple of Jupiter Stator was rebuilt after the fire of 64 AD and [then] mentioned in [the regionary catalogues of the ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’]. It is represented in a relief from [the Tomb of the Haterii], identifiable thanks to the cult statue at the centre of the edifice, which represents Jupiter with his legs embedded in a block of stone” (my translation).

This location was consistent with Peter Wiseman’s view (above) that Plutarch had placed the rebuilt temple at a point on the Sacra Via close to the Forum and with his suggestion that Nero had built it across the Sacra Via from the House of the Vestals.

In a related article in the same book, Fabio Cavallero (referenced below, p. 209) discussed the situation as it existed after the fire of 191/2 AD. He identified the apsed hall of Vespasian’s Templum Pacis immediately behind the rebuilt temple as a library, and asserted that:

-

“Beyond the library, set among the Neronian arcades and oriented along the Sacra Via, was the Temple of Jupiter Stator, the architecture of which can be reconstructed thanks to the Haterii relief.” (my translation).

The arrangement is depicted in this topographical context in Volume 2, Table 99.

My Assessment

Fabiola Fraioli proposed this site for the Flavian temple primarily because she believed that it had been the site of Atilius’ original temple. I concluded in my page on Victory Temples and the Third Samnite War that the literary sources do not place Atilius’ temple on the Sacra Via, but rather on the lower slopes of the Palatine. However, Plutarch placed it on the Sacra Via after the fire of 64 AD, so this site needs to be considered as the possible location of the temple at that time. Indeed, if one accepts Peter Wiseman’s interpretation of Plutarch’s account (above), it was at this end of the Sacra Via (i.e. near the Forum). The site has two other advantages:

-

✴Since there is no surviving archeological evidence for an otherwise unidentified Flavian temple in this heavily excavated area, this is perhaps the only location at this end of the Sacra Via that can be considered.

-

✴It is certainly in regio IV, as required by the regionary catalogues, albeit not in the precise location suggested by the sequence of monuments therein (as discussed below).

However, there is a problem with this scenario, as demonstrated by:

-

✴the tables that illustrate Fabiola Fraioli’s hypothesis (particularly Table 99); and

-

✴my diagram (above), in which I have mapped the Flavian temple, as reconstructed by Fabiola Fraioli from the Haterii relief, onto the later structures on the site:

-

•the Maxentian rotunda and its side aisles; and

-

•the church of SS Cosma e Damiano (6th century AD), which occupied part of the ex-library of the Templum Pacis (the original apse of which, shown in the plan, was demolished as part of the Maxentian development).

It is clear from these reconstructions that Fraioli’s hypothesis requires us to accept that Atilius’ impressive temple (which had been large enough to accommodate the Senate) had been rebuilt as a shallow structure appended to the library of Vespasian’s Templum Pacis (almost as an after-thought).

It is, of course, possible that the temple pre-dated the Templum Pacis, and that it had subsequently been truncated to make way for its library, perhaps receiving its apparently Flavian facade at this time. However, there is no evidence and no obvious reason for this putative chain of events (which is probably why no-one has suggested it, as far as I know). It seems to me that a site between the library of the Templum Pacis and the later Temple of Antoninus and Faustina to the west of it would be a better solution, although there is no archeological evidence to support this. (Giuseppe Lugli (referenced below, at p. 122) mentioned remains here of an apsed hall, which he dated to the Severan period. He suggested might have belonged to the schola kalatorum pontificum et flaminium, a guild of freedmen attached to the pontifices and flamines), known from inscriptions found close to the nearby Regia.)

Regionary Catalogues of the 4th Century AD

The two regionary catalogues mentioned above are included in a codex known as the ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’, which is named for its illustrated calendar. Each of these catalogues includes a list of the important monuments of the city, grouped according to the 14 regions as designated by the Emperor Augustus in 7 BC, in which each region was given its popular designation as well as its official numbers. The original text of this part of the codex is known only in two later versions:

-

✴The first of these, which is untitled, is known as the ‘Notitia urbis Romae regionum XIV’. It must post-date 334 AD (since it refers to the equestrian statue of Constantine, dedicated in that year) and possibly pre-dates 357 AD (since it does not mention the 2nd obelisk that Constantius II erected in the Circus Maximus).

-

✴The other has the title ‘Curiosum urbis Romae regionum XIIII’. Since it mentions the 2nd obelisk in the Circus Maximus, it must post-date 357 AD.

According to Samuel Platner (referenced below, at p. 5):

-

“The common original [of these two lists] was probably compiled between 312 and 315 AD, and was itself based on a similar document of the 1st century AD.”.

The on-line version of the the codex in the website Tertulian.org, which is taken from Heinrich Jordan’s ‘Topographie der Stadt Rom in Alterthum’, Volume II (1871), includes the ‘Notitia’ and the ‘Curiosum’, arranged side-by side, as: ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’: Part 14.

As noted above, these catalogues include an aedes Iovis Statoris under regio IV (Templum Pacis). The relevant extracts are as follows:

-

“REGIO IV: TEMPLVM PACIS continet [i.e. contains]:

Notitia: Curiosum:

... ...

[colossal statue] [colossal statue]

Metam sudantem Metam sudantem

Templum Romae et Veneris Templum Romae

Aedem Iovis Statoris Aedem Iobis

viam Sacram viam Sacram

Basilicam Constantinianam Basilicam novam et Pauli

Templum Faustinae Templum Faustinae

Basilicam Pauli [see Basilicam novam et Pauli above]”

... ...

Traditional View

Adam Ziolkowski (referenced below, 2015, pp. 578) set out the traditional view:

-

“.... the order of the securely identified monuments of regio IV leaves no doubt as to their clockwise sequence. If so, we must locate the temple of Jupiter Stator between the east end of the precinct of Venus and Roma and the basilica [Constantiniana/ nova]; and the only temple-like structure in that area is the podium by the Arch of Titus [marked ‘Z’ on the plan above].”

This, of course, assumes that both the Arch of Titus and the podium slightly to the southeast of it were in regio IV rather than in the adjacent regio X (Palatium). Surprisingly, the Arch of Titus was not listed in either of the surviving versions of the catalogue, so that cannot settle the matter, and no other securely identified monument in the respective regions is of much help in defining the boundary between them (a point discussed further below). All one can certainly conclude from the sequence of monuments above is that, if the podium actually was in regio IV, then it would be a candidate for the site of the aedes Iovis Statoris in the 4th century.

However, this raises a problem: on the traditional view, the podium was essentially on the site of Atilius’ temple. However, this temple was recorded ‘in Palatio’ in the the Fasti Privernates, which probably dates to a period shortly before or shortly after the creation of the formal administrative regions in 7 BC (as discussed in my page on Victory Temples and the Third Samnite War). This suggests that it was most probably in (or, about to be included in) regio X (Palatium). Adam Ziolkowski argued (at pp. 580-1) that:

-

“There are two ways to account for this discrepancy...:

-

-[Perhaps the] temple changed position. [This] is quite probable: the podium by the Arch of Titus belongs to the post-Neronian arrangement of the zone while [topographical considerations suggest that Atilius’] temple stood slightly to the south of [it], in what is now the NW corner of the Vigna Barberini complex. But could such a tiny change land it in a different region [before and after the fire]? ....it is more probable that, in such cases, boundaries followed the shifts of important monuments.

-

-[Alternatively, perhaps the limits of the Palatine changed at some point]: the best occasion [on which this might have happened] .. was surely not Nero’s fire but the administrative shake-up that was [associated with] the creation of the Augustan urban regions [in 7 BC]. ... The Augustan reform required a precise delimitation of the new regions, not least because it divided the old tribus Palatina, separating:

-

-the hill [itself], now regio X; from

-

-the Sacra Via and the Velia [to the north of it], which ... now became regio IV”.

In other words, (on this view, if I have understood it correctly), although the temple stood on the lower slopes of the Palatine, and could therefore be described as ‘in Palatio’ in common parlance, administrative considerations in 7 BC had probably led to the inclusion of these lower slopes in regio IV rather than in regio X.

Filippo Coarelli’s View

Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, 1983, pp. 24-6) has long argued that the Sacra Via formed the boundary between regio IV and regio X along its length, and that everything to the south of it was in regio X. He reiterated this proposition in his recent book (reference below, 2012, at p. 105):

-

“Regio IV: here we find one of the most significant and coherent topographic series [of monuments] in the catalogues.”

He then argued that, starting in the east, the vicus between:

-

✴the colossal statue in regio IV (see the lists above), which was to the east of the Temple of Venus and Roma (i.e. off the plan above, to the right); and

-

✴the adjacent amphitheatre (Colosseum), further still to the east and in regio III;

clearly constituted the boundary between these regions. He continued (at p. 106):

-

“In my opinion, there is no valid argument that would deny the next part of the list, from the Meta Sudans to the basilica Pauli, an analogous function in regard to the boundary between regio IV and regio X” (my translation).

He argued that all the identifiable monuments between the Temple of Venus and Roma and the basilica Pauli (i.e. all of those in the list except the unidentified aedes Iovis Statoris) were on the north side of the Sacra Via. This included the basilica Pauli itself, which was clearly physically in the Forum. He concluded (at p. 106) that:

-

“In view of this, there can be no doubt about the identification of the boundary line [of regio IV, which was] clearly marked by the Sacra Via” (my translation).

In other words, the aedes Iovis Statoris had to be on the north side of the Sacra Via, and thus could not have stood on the podium southeast of the Arch of Titus, which was (on this view) in regio X.

The sequence of monuments in regio IV, which would place the aedes Iovis Statoris between the Temple of Venus and Roma and (from ca. 307 AD) the basilica Constantiana/nova, a location that I have marked ‘P’ on the plan above. However, Filippo Coarelli (for example, in his guide book of 2007/14, at p. 90) argued that there was no room for it here (pariculary if one ruled out the south side of the Sacra Via, which he did). Further:

-

“The only monument ... [in this sequence] that has not been identified is [the Maxentian rotunda, which stands between the basilica Constantiana/nova and the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina]. ... Accordingly, [the aedes Iovis Statoris] and the [rotunda] must be one and the same.”

Coarelli later came to believe that this rotunda was only dedicated to Jupiter Stator after Constantine took Rome in 312 AD. However, Fabiola Fraioli used his argument for her contention (above) that:

-

“On the Sacra Via, the Temple of Jupiter Stator was rebuilt after the fire of 64 AD and [then] mentioned in [the regionary catalogues of the ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’]” (my translation).

My Assessment

Adam Ziolkowski, in his review (referenced below, 2015, pp. 575-9) of Filippo Coarelli’s book argued that:

-

“... the [regionary catalogues] do not specify the boundaries of the regions; they only name objects within those boundaries. The only securely identified item of regio X facing the securely identified items of regio IV is the Domus Tiberiana [a short distance to the south of the Sacra Via] ..., which means that the boundary between the two regions must have run in between: everything beyond that requires additional evidence and/or argument.”

In other words, there is no firm evidence on which the buildings along the south side of the Sacra Via can be assigned either to regio IV or to regio X. Filippo Coarelli may well have been correct when he claimed (above) that:

-

“... there is no valid argument that would deny [to the monuments in the regionary lists] from the Meta Sudans to the basilica Pauli [the function of defining] the boundary between regio IV and regio X” (my translation).

However, that falls short of establishing beyond doubt that these monuments did indeed function in this way. (One also has to wonder whether it made sense for the lists to ‘contain’ the Sacra Via itself while excluding the buildings that opened onto it from the south).

In short, the regionary catalogues themselves cannot be used to decide definitively whether the aedes Iovis Statoris of regio IV was more probably in location ‘Z’ or location ‘F’ on the plan above:

-

✴we just do not know whether location ‘Z’ was:

-

•in regio IV (as claimed by Adam Ziolkowski); or

-

•in regio X (as claimed by Filippo Coarelli); and

-

✴while location ‘F’ is securely in regio IV, but the sequence of monuments in this region appears to place the aedes Iovis Statoris on the opposite side of the basilca nova.

My View on the Temple’s Location

Evidence of Plutarch and the Regionary Catalogues

I think that the debate should start with the sequence of monuments in regio IV, which would place the aedes Iovis Statoris between the Temple of Venus and Roma and the later site of the basilica Constantiana/nova, a location that I have marked ‘P’ on the plan above. Further, since regio IV could extend slightly to the south of the Sacra Via, it might have been on either side of the street. It seems to me that this location:

-

✴is consistent with Plutarch’s assertion that, by 92 AD, the Temple of Jupiter Stator was:

-

“... situated at the beginning of the Sacra Via, as one goes up to the Palatine” (‘Life of Cicero’, 16:3); and

-

✴fits Plutarch’s description more naturally than either location ‘F’ or location ‘Z’.

Evidence of the Haterii Relief

We might also usefully consider location ‘P’ in the context of the Haterii relief discussed above. Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, 2009, p. 429) observed that:

-

“The nature and the locations of the [five monuments in this relief] are much discussed. One faces essentially two theories:

-

•according to the first, one is dealing with monuments built at various [unrelated] locations in the city; while

-

•according to the second, the monuments are arranged [in the relief] in topographical order.

-

Given the presence of at least two monuments that are certainly situated in locations relatively close to each other (the ‘Arcus in Sacra Via summa’ and the Colosseum), we might lean towards the second solution, which also allows the location of the other monuments [to be deduced] without too much trouble” (my translation).

A full analysis of this suggestion is outside the scope of this page. Nevertheless, it is possible that the ‘Arcus in Sacra Via summa‘ and the Temple of Jupiter Stator were placed in adjacent fields in the relief to reflect their actual proximity. If so, this would allow us to locate the temple by locating the summa Sacra Via and its eponymous arch

In fact, as Filippo Coarelli (referenced below, 2012, at p. 481) pointed out, the name given to this arch makes it almost certain that it was:

-

“... along the last stretch of the post-Neronian Sacra Via, almost at its end point, which is occupied now by the Temple of Venus and Roma” (my translation).

Giuseppe Lugli (referenced below, at pp. 168-9) made this association as long ago as 1947:

-

“One reads a reference to the Sacra Via summa on the large arch sculpted on the well-known Haterii relief: it is indicated as well: by Augustus, for the Temple of the Lares; and by Plutarch, for the Temple of Jupiter Stator” (my translation).

Thus, it can be argued that the relief of Flavian monuments from the Haterii Tomb provides some support for location ‘P’ as the site of the temple.

Evidence from the Coins of Antoninus Pius

In his 3rd Consulship (140 AD), Antoninus Pius issued:

-

✴ten coins that almost certainly commemorated the completion of the Temple of Venus and Roma; and

-

✴five coins that depicted Jupiter Stator (identified by inscription) on their reverses.

In itself, this would not be particularly significant. However:

-

✴this was the first time that Jupiter Stator had featured in the Imperial coinage; and

-

✴it was to be almost a century before he made his next appearance (on the reverse of RIC IV Severus Alexander 202; and on those of eleven coins issued by Gordian III).

It seems to me that these two unusual and substantial issues of 140 AD must have related to:

-

✴either a victory of some sort that had been achieved after a Roman rout had been averted; or

-

✴the rebuilding or restoration of one or other of the two temples to Jupiter Stator in Rome.

The temporal coincidence of Antoninus Pius’ coins commemorating the completion of the Temple of Venus and Roma and those with Jupiter Stator reverses suggests the second of these possibilities. Specifically, I think that the Flavian temple of Jupiter Stator had to be rebuilt or extensively restored as a consequence of the erection of the Temple of Venus and Roma at the end of the Sacra Via. If it had had to be demolished in order to make way for the new temple, then the sequence of the monuments in the regionary catalogues suggests that it was rebuilt on an adjacent site on the Sacra Via and hence at location ‘P’.

Evidence from the Panegyric of 289 AD

This temple was probably mentioned in a panegyric (Panegyric X, translated into English in Nixon and Rodgers, referenced below) that was delivered at the court of the Emperor Maximian at Trier in 289 AD to mark the anniversary of the foundation of Rome:

-

“O [Maximian], how much more majestic [Rome] would be now, how much better would she celebrate this her birthday, if she were viewing you [in the flesh]. Now, doubtless, her citizens are imagining that you are present by flocking to the temples to your divinities and ... repeatedly invoking Jupiter Stator and Hercules Victor” (13:4).

At this time, Maximian ruled alongside his senior colleague Diocletian, and their respective divine patrons were Hercules and Jupiter. The “temples to your divinities” to which the Romans flocked to experience the virtual presence of these habitually absent Emperors were apparently those of Jupiter Stator and Hercules Victor. Obviously, it is this Temple of Jupiter Stator that is of interest here.

There were actually two temples to Jupiter Stator in Rome: the second was in the Porticus Metelli (discussed in the page on the Victory Temples of 146 BC)). However, the panegyrist more probably referred to the more venerable temple on the Sacra Via, particularly if (as suggested above) it was close to the Temple of Venus and Roma, where the anniversary of the foundation of Rome was celebrated. If this temple was one of the loci of the virtual presence of Diocletian and Maximian, we can reasonably assume that their images were prominently displayed nearby, accompanied after 293 AD by images of their newly-appointed Caesars, Constantius and Galerius (as discussed in my page on the Imperial Cult (285-305 AD)).

In fact, the base of a statue of Maximian was found in ca. 1530 in the Farnese gardens, on the northern slope of the Palatine above the Sacra Via. Its inscription (CIL VI 1125; LSA-820, discussed in my page on the first Tetrarchy) revealed that:

-

✴it had been erected by Septimius Valentio, who the vicar of the two Praetorian Prefects in Rome; and

-

✴it had been erected after Maximian’s 4th Consulship but before his 5th (i.e. in the period 293-6 AD).

Since the Tetrarchs were usually portrayed together, it is tempting to speculate that this was one of four statues that Septimius Valentio erected to mark the formation of the Tetrarchy in 293 AD. Whether or not this was the case, Maximian’s statue was an important commission and we may reasonably assume that its location would have been chosen for its political resonance. Given the remarks in the panegyric above, the obvious location would have been the nearby Temple of Jupiter Stator.

Fortunately, Rodolfo Lanciani (referenced below, search on “PENATIVM” in the on-line text) recorded details of the excavations that had led to the discovery of the statue base:

-

“1530: AEDES PENATIVM IN VELIA. Approximate date of the excavations of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese on the slope of the Palatine, towards the Forum Romanum.

-

-Here was found the pedestal ‘Laribus publicis sacrum’ dedicated by Augustus on 1st January [on the 750th anniversary of the foundation of Rome - i.e. ca. 4 BC], evidenced by the inscription] (CIL VI 0456).

-

-Here must also have been brought to light the large base of marble with a damaged inscription dedicated to Maximian by Septimius Valentio (CIL VI 1125)” (my translation).

This suggests that the statue of Maximian had originally stood near the Temple of the Lares, which can be located by a passage in Augustus’ ‘Res Gestae’;

-

“I built: ... the Temple of the Lares ‘in summa sacra via’; ...” (4:19).

It was still there in the 3rd century AD, when Solinus included the following information in his account of the locations of the palaces of the original kings of Rome:

-

“Ancus Marcius [lived] in summa sacra via, where the aedes Larum is situated” (‘De mirabilibus mundi’, 1:23)

If one accepts that the statue of Maximian was also probably near the Temple of Jupiter Stator (as suggested above), then this is further circumstantial evidence in favour of placing this temple in location ‘P’.

Conclusion

I argued above that evidence for location ‘P’ can be found: from Plutarch; from the Haterii relief; and from the coins of 140 AD; and (indirectly) from the panegyric of 289 AD. However, it is unlikely that a temple at this end of the Sacra Via would have remained unaffected by the fire that seriously damaged the Temple of Venus and Roma in ca. 307 AD. It could have been rebuilt thereafter, but:

-

✴Maxentius’ basilica nova took up all the space to the north of the Sacra Via soon after the fire; and

-

✴there is no archeological evidence for temple on the opposite side of the street.

How then are we to account for the record of the aedes Iovis Statoris in this location in the regionary catalogues in the ‘Chronograph of 354 AD’?

It seems to me that there are three possible answers to this question:

-

✴the aedes Iovis Statoris was destroyed by the fire and its remains were obliterated by the subsequent construction of the basilica nova, but it was not (for whatever reason) removed from the regionary catalogues;

-

✴Maxentius, who restored the Temple of Venus and Roma after the fire, also restored or rebuilt the aedes Iovis Statoris on a site opposite his basilica nova, albeit that no such project is documented and no archeological remains of it have been found; or

-

✴the aedes Iovis Statoris was rebuilt on a new location after the fire, but the lists in the regionary catalogue were not updated to reflect this development.

I consider these possibilities in my page on Maxentius and the Temple of Jupiter Stator.