The Etruscans

Etruscan Religion

Home Cities History Art Hagiography Contact

The Etruscans: Main page Etruscan Language and Culture

Early Etruscan Inscriptions Etruscan Religion

Return to the History Index

The Etruscans

Etruscan Religion

Home Cities History Art Hagiography Contact

The Etruscans: Main page Etruscan Language and Culture

Early Etruscan Inscriptions Etruscan Religion

Return to the History Index

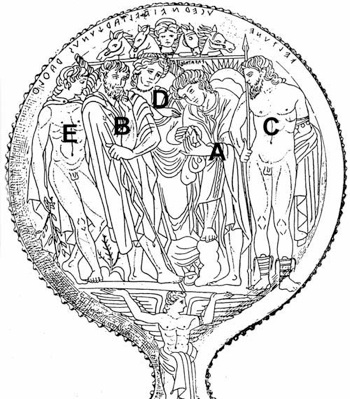

Bronze mirror (early 3rd century BC) from Tuscania

Museo Archeologico, Florence

A = ‘Pava Tarchies; B = ‘Avl Tarchunus’ ; C = ‘Veltune’ (C); D = ‘Ucernei’ ; E = ‘Rathlth’

Jean MacIntosh Turfa (referenced below, at p. 20) the fundamental fact that characterised and distinguished the religious beliefs of the Etruscans:

“... unlike Greek and Roman practice, Etruscan religious doctrine was based on received scripture. A prophet [known to the Romans as Tages] had revealed the words of the gods [to them, and these words] were formally recorded and preserved by priestly, aristocratic families.”

The Etruscans who later occupied the (traditionally twelve) Etruscan city-states would have been conscious of their shared ethnicity, not only because of their shared language but also because of their shared religious heritage. We know that they attributed the latter to a particular event that must have been part of a foundation myth, because their accounts of it survived into the Roman period and, although they were subsequently lost, they may well be reflected in what Nancy Thomson de Grummond (referenced below, at p. 27) described as:

“... a mixed lot [of surviving non-Etruscan sources, ... all of which] seem to have had access to antiquarian sources that may reflect original Etruscan writings.”

She cited, in particular:

✴Cicero, in a work written in ca. 44 BC;

✴Verrius Flaccus, an Augustan authority whose now-lost work was epitomised by Festus in the 2nd century AD; and

✴John Lydus, a Byzantine authority of the 6th century AD.

This tradition might well explain the scene depicted on the bronze mirror (early 3rd century BC) from Tuscania [Etruscan Tusena] that is illustrated above. Nancy Thomson de Grummond (referenced below, at pp. 29-30) described the scene, in which:

✴‘Pava Tarchies’ (A), who stands at the centre, wears a conical cap that indicates the he is a priest and stands in a ritual pose as he contemplates the liver of what was probably a sacrificed animal;

✴‘Avl Tarchunus’ (B), an older priest to his right, whose similar conical hat is pushed back and who watches him intently;

✴‘Veltune’ (C), a nude, bearded man with a spear who stands behind ‘pava tarχies’ and looks over his shoulder (at the extreme right of the composition);

✴‘Ucernei’ (D), a lady who stands conspicuously behind and between ‘pava tarχies’ and ‘avl tarχunus’ and reaches out towards the liver; and,

✴‘Rathlth’ (E), who carries a laurel branch (at the extreme left).

Nancy Thomson de Grummond (referenced below, at p. 29) observed that, although the significance of the presence of the last two figures is unclear:

“No better explanation has been found [for this iconography than that of Massimo Pallottino, referenced below]: we have here the myth of Tages (pava may mean puer or child, [and] tarχies could become Tages in Latin) instructing Tarchon, or perhaps his son, whose name would then be avl, in haruspicina”

I discuss the possible significance of the presence of Veltune here in my page on the Etruscan League in the Republican Period.

There were a number of other specifically Etruscan divinities, including the sun god Usil and the goddess Nortia. By the 5th century BC, the Etruscans had begun to add the Greek gods to their pantheon, although their religion continued to differ profoundly from that of the Greeks. These Greek divinities included Tinia (Zeus), Uni (Hera), Vei (Demeter) and Larans or Maris (Ares, Roman Mars), as well as Aita and Phersipnai (Hades and Persephone), the god and goddess of the underworld. The Etruscans also Varro the Greek heroes, including and the heroes of the Trojan Wars.

The Etruscans probably first worshipped their gods in sacred groves, but temples began to appear in the 6th century BC, and once again the rituals for their foundation and liturgical practices were set out in the disciplina Etrusca.

The Etruscans were quite fatalistic, believing that the life spans of men and also of the Etruscan nation were predetermined. They seem to have believed that the dead faced a difficult journey to the underworld but that, once there, they would meet their ancestors at an eternal banquet. Success in the journey was determined by the rites that the relatives and friends of the deceased observed on his or her behalf, as set out in the disciplina Etrusca. These included ritual games and dances and the use of appropriate grave furniture. A male and a female demon, respectively Charu and Vanth guarded the gates to the underworld. The former was named for Charon, the Greek ferryman but generally armed with a hammer rather than (as in Greece) with oars.

At least by the time of its destruction by the Romans in 264 BC, Volsinii seems to have been the religious capital of the Etruscans:

✴The regular meetings of the representatives of the Etruscan cities took place at a shrine that the Romans called “voltumnae fanum” (the sanctuary of Veltune/Voltumna), which was probably near Volsinii.

✴According to Livy, “Cincius, a careful writer on such monuments, asserts that there were seen at Volsinii also nails fixed in the temple of Nortia, a Tuscan goddess, as indices of the number of years”.

Both of these deities seem to have been “called” to Rome when the city fell.

Revelation of Tages

Cicero

The earliest surviving version of this mythical revelation is preserved in a work by Cicero 0f ca. 44 BC:

“The tradition [relating to the origins of soothsaying] is that, once upon a time, in the district of Tarquinii, while a field was being ploughed, the ploughshare went deeper than usual and a certain Tages suddenly sprang forth and spoke to the ploughman. Now this Tages, according to the Etruscan annals, is said to have had the appearance of a boy but the wisdom of a seer. Astounded and much frightened at the sight, the rustic [ploughman] raised a great cry; a crowd gathered and, indeed, in a short time, the whole of Etruria assembled at the spot. Tages then spoke at length to his numerous listeners, who eagerly received all that he said and committed it to writing. His whole address was devoted to an exposition of haruspicina disciplina (the science of soothsaying, which the Romans referred to as Etrusca disciplina]. Later, as new facts were learned and tested by reference to the principles imparted by Tages, they were added to the original fund of knowledge. This is the story as we get it from the Etruscans themselves and as their records preserve it, and this, in their own opinion, is the origin of their [divinatory] art”, (‘De Divinatione’, 2: 23).

However, Cicero then revealed what he thought of this Etruscan lore:

"Who in the world is stupid enough to believe that anybody ever ploughed up (which shall I say, a god or a man) ?

✴If a god, why did he, contrary to his nature, hide himself in the ground to be uncovered and brought to the light of day by a plough? Could not this so-called god have delivered this art to mankind from a more exalted station ?

✴But if this fellow Tages was a man, pray, how could he have lived covered with earth ... [and] where had he learned the things he taught others ?

In fact, in spending so much time in refuting such stuff, I am more absurd than the very people who believe it”, (‘De Divinatione’, 2: 23).

Thus, although Cicero’s version of the myth is often taken as canonical, J. R. Wood (referenced below, at p. 237) reasonably pointed out that:

“Cicero himself actually warns us that his version ... is a caricature, so that his account can be interpreted as a satirical distortion ... of the original [that he found in his Etruscan sources].”

He expanded this point (at p.340) by observing that, in the light of Cicero’s concluding lines:

“... we must expect neither accurate report nor impartial exegesis [in the lines that precede them]. ... [Cicero] claims to be quoting [the books of the Etruscans, which were probably available in Latin by his time - see note 18]:

✴I do not argue that [this claim was incorrect]: he reflects too much of the detail in ... surviving fragments [of this work that were probably used by other Roman and Greek authors] not to have shared the common source.

✴[Rather, I argue that] Cicero has transmogrified [this ‘Roman’ original], happily tipping his polemical point with barbs of satire.”

John Lydus

John Lydus recorded that

“Tarchon [the Elder] ... was ... a haruspex, one of those who were taught by Tyrrhenos the Lydian. .... [Tarchon] tells that something miraculous happened to him by chance when he was ploughing once upon a time. .... A little boy appeared from a furrow; he seemed to be new born but nevertheless had teeth and other markings of great age. This little boy was Tages ... When Tarchon ... had lifted up the child and placed him on a sacred place, he asked him to teach him the secrets [of divination]. His request was granted. Based on the sayings, Tarchon wrote a book in which he asks questions in [Latin], but Tages’ answers have archaic elements which are unknown to us [i.e. they were in Etruscan]” (“De Ostentis”, 2: 6, translated by Nancy Thomson de Grummond (referenced bellow, at p. 193)”

We learn from this (inter alia) that the ploughman to whom Tages appeared was none other than Tarchon, the founder of the twelve cities.

Marcus Verrius Flaccus

Verrius Flaccus, an Augustan authority whose now-lost work was epitomised by Festus in the 2nd century AD, gave Tages’ lineage as follows:

“... Tages, [who was] the son of Genius and grandson of Jupiter, is said to have given the disciplina haruspicina to duodecim populis Etruriae (the twelve peoples of Etruria)”, (‘De significatu verborum’, 492L)

Read more:

Macintosh Turfa J., “Divining the Etruscan World”, (2012) Cambridge

Thomson de Grummond N.., “Prophets and Priests”,in:

Thomson de Grummond N. and Simon E. (editors), “The Religion of the Etruscans”, (2006) Austin TX, at pp. 27-44

Wood J., 'The Myth of Tages', Latomus, 39:2 (1980), 325-44

The Etruscans: Main page Etruscan Language and Culture

Early Etruscan Inscriptions Etruscan Religion

Return to the History Index