Adapted from this page in Wikipedia

Note that the identities of the twelve ‘Etruscan League cities’ above are hypothetical,

and that (as discussed below), even if there was a formal league of 12 Etruscan cities existed at this time,

Fufluna (later Roman Populonium) is unlikely to have been one of them

By at least the 8th century BC, the people that we know as the Etruscans occupied a tract of central Italy that extended from the later site of Rome to the Arno valley, and from the west coast of the peninsular to the Tiber. The Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus included a careful study of these people (whom he knew by the Greek name ‘Tyrrhenians’) in the first book of his ‘Roman Antiquities’ (which he published in Rome in 7 BC). He noted that they belonged to:

-

“... a very ancient nation, and [share] with no other either [their] language or [their] manner of living. The Romans .... [knew them as]:

-

✴the Etruscans, from the country that they once inhabited, named Etruria,; and

-

✴now (rather inaccurately) Tusci, from their knowledge of the ceremonies relating to divine worship, in which they excel ... .

-

However, their own name for themselves is ... ‘Rasenna’”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 30: 4).

Etruscan Velzna and Perusia

Orvieto: Etruscan Velzna until 264 BC, Perugia: stretches of the walls of Etruscan

with the excavated Etruscan sanctuary at Perusia survive beneath the medieval circuit

Campo della Fiera is in the foreground

According to Pliny the Elder, when the Emperor Augustus reorganised the administrative structure of Italy in 7 BC:

-

✴most of the ancient cities that are now in modern Umbria were included in the Sixth Region, ‘Umbria and the Gallic territory’ (‘Natural History’, 3:19); but, since

-

✴two of them have Etruscan roots, they were included in Seventh Region, ‘Etruria’, (‘Natural History’, 3:8):

-

•the city of the Volsinienses, (i.e. Volsinii, Etruscan Velzna), which was probably on the later site of Orvieto until 264 BC, when the the Romans destroyed it and moved its inhabitants to the shores of Lake Bolsena; and

-

•Perusia (modern Perugia).

These peoples were culturally distinct from the their Umbrian neighbours, and are therefore treated separately here.

Who Were the Etruscans?

Origins of the Etruscans

Dominique Briquel (referenced below, at p. 36) observed that, prominent among the ‘mysteries’ surrounding the Etruscans is:

-

“... the age-old question of their origins.”

This debate has hardly moved on since at least the time of Dionysius (above), who observed that:

-

“... some declare [the Tyrrhenians] to be natives of Italy, but others [assume them to have been] foreigners”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 26: 2).

He then expanded in some detail on the merits or otherwise of these competing theories. For example:

-

“Those who make them a native race say that they were named for the fact that they were the first of the inhabitants of this country to build forts (since covered buildings enclosed by walls are called tyrseis or towers by both the Tyrrhenians and the Greeks)”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 26: 2).

He also discussed a number of theories relating to their putative ‘foreign’ origins, which fall into two groups:

-

✴“... [some, including the Greek historian Herodotus, who wrote in the 5th century BC - see below] say that Tyrrhenus [who founded the original] colony, gave his name to the nation, and that he was from Lydia [in modern Turkey] ...”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 27: 1).

-

✴“Hellanicus of Lesbos, [who also wrote in the 5th century BC], says that the Tyrrhenians, who were previously called Pelasgians [a name associated with the Aegean], received their present name after they had settled in Italy”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 28: 3).

Finally, he gave a reasoned argument in favour of his own conclusions. In his view:

-

“... it is unreasonable [to believe] that men sprung from the same race and living in the same country should [disagree] with one another in their language. For this reason, I am persuaded that the Pelasgians are a different people from the Tyrrhenians. Furthermore, I do not believe that the Tyrrhenians were a colony of the Lydians: they do not use the same language as the [Lydians] and they neither worship the same gods ... nor make use of similar laws or institutions. Indeed, in these respects, [the Tyrrhenians] differ more from the Lydians than they do from the Pelasgians. [It therefore seems to me] that those who declare that [they were] ... native to the country probably come nearest to the truth ... [After all], there is no reason why the Greeks should not have called them [‘Tyrrhenians’], both from their living in towers and from the name of one of their rulers.”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 1: 30: 1-2).

Ancient League of Twelve Etruscan Cities ?

As noted above, Herodotus, held that the Etruscans had originated in Lydia. Indeed, he might have been one of the sources consulted some 400 year later later by Dionysius (above). Fortunately, the relevant text still survives:

-

“In the reign of Atys, son of Manes, there was great scarcity of food in all Lydia. ... At last, [Atys] divided the people into two groups, and made them draw lots, so that the one group should remain and the other leave the country; Atys himself was to continue as the leader of those who [remained, while] his son, whose name was Tyrrhenus, [was to became the leader] of those who ... sailed away to seek a livelihood [elsewhere]. At last, after sojourning with one people after another, [the latter group] came to the[land of the] Ombrici [i.e., of the Umbrians of central Italy], where they founded cities and have lived ever since. They no longer called themselves Lydians, but Tyrrhenians, after the name of the king's son who had led them there”, (‘The Histories’, 1: 94: 3-7).

In Dionysius’ own time, another Greek historian, Strabo recorded the number of these original cities:

-

“[Tyrrhenus] not only called the [new] country Tyrrhenia after himself, but also put Tarco in charge as ‘coloniser’ and founded twelve cities ...”, (‘Geography’, (5: 2: 2 ).

Although, as discussed above, the theory of the Etruscans’ Lydian origins was not universally accepted even among ancient scholars, Strabo’s motif of the early and simultaneous foundation of twelve Etruscan cities in the pre-Roman period took root.

Strabo, Servius and the Case of Populonium

Strabo also recorded that, in his opinion, the city on the Tyrrhenian coast that the Romans knew as Populonium:

-

“... is the only one of the ancient Etruscan cities that was situated on the sea ...” ‘Geography’ (5:2: 6).

Virgil (‘Aeneid’, 10: 172), who was writing at about the same time, obviously concurred that Populonium was indeed an ancient Etruscan city, since he included it among those that sent forces to the assistance of the Trojan Aeneas in his war against Turnus. In his commentary on this passage (written in ca. 400 AD), Maurus Servius Honoratus (‘ad Aen’, X: 172) gave three versions of the city’s origins:

-

✴it was founded by people from the nearby island of Corsica ‘post XII populos in Etruria’ (after the arrival of the twelve peoples of Etruria);

-

✴it was a colony of Volaterrae, (which he presumably counted as one of the twelve original colonies); or

-

✴it was founded by the Corsicans (as above), but they were subsequently expelled by the Volaterrani.

What is important here for our purposes is that Servius clearly concurred with Strabo’s motif of the simultaneous foundation of twelve Etruscan cities in Italy long before the foundation of Rome.

Ancient League of Twelve Etruscan Cities: Conclusions

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 403) argued that, since:

-

“... a league of twelve [Etruscan] cities is mentioned [by both Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus in their accounts of the Regal period, and since] these annalistic passages are supported by [both Strabo and Servius], ... it would be foolish to doubt that such a league existed ... , [albeit that] it seems doubtful whether [it] had a military (as opposed to a religious) function. The annalists [including Livy and Dionysius] will thus have exploited these religious festivals, about which they were well informed, and given them a political interpretation. ... We cannot be certain about the exact constitution of [this putative] league, although the twelve cities may have been [those known by the Romans as]: Arretium; Caere [Caesra on the map above]; Clusium [Clevsin]; Cortona [Curtun]; Perusia; Rusellae [not included on the map above]; Tarquinii [Tarchna]; Veii; Vetulonia [Vetluna]; Volaterrae [Felathri]; Volsinii [Velzna]; and Vulci [Velch].”

Oakley’s list excluded Populonium [Fufluna], presumably on the basis of Servius’ testimony, and instead included Rusellae (Etruscan Rasela or Rusle) near Vetulonia.

Etruscan Language

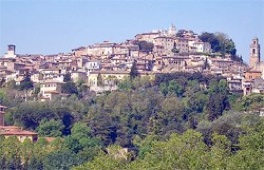

Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis (ca. 200 BC), the longest surviving example of written Etruscan

from the website of the Archeological Museum of Zagreb

Sybille Haynes (referenced below, at p. 1) observed that:

-

“The Etruscan people become linguistically (and thus historically) identifiable as such around 700BC, when the oldest Etruscan inscriptions appear on pottery found in southern Etruria.”

The point that she was making is that, unlike most other ancient peoples, the Etruscans are readily identified by their language, which Dionysius had characterised as unrelated to any other. In particular, they were the only ancient people of central Italy whose language did not belong to the group known as ‘Indo-European’.

Larissa Bonfante (referenced below, 2006, at p. 9) pointed out that students of this unusual language are constrained by the fact that:

-

“We have no Etruscan literature, no epic poems, no religious or philosophical texts.”

However, the survival of some 10,000 Etruscan inscriptions, of which at least 75 date to the 7th century BC, provides ample evidence that Etruscan was a written language from an early date, and that it employed an alphabet that was adapted from that of the Greeks. Unfortunately, most of these inscriptions contain only a few words and, the majority of these are epitaphs. Bonfante also pointed out (at p. 10) that the few surviving:

-

“... longer texts are technical, religious and ritual, confirming the reputation of the Etruscans for being skilful of dealing with the gods ...”

The result of these two basic facts:

-

✴that Etruscan resembles no other known language; and

-

✴that the only surviving examples of it are short and/or highly specialised;

is that, as Larissa Bonfante (referenced below, 1990) at p. 330) observed:

-

“... Etruscan remains an unknown language written in a known script.”

Etruscan Religion

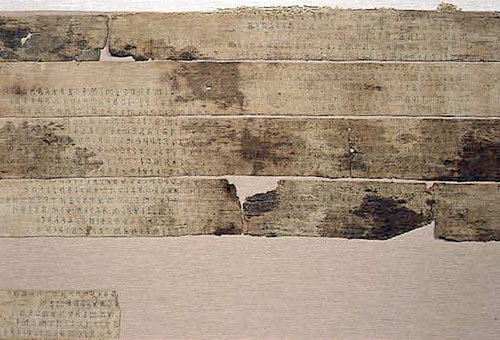

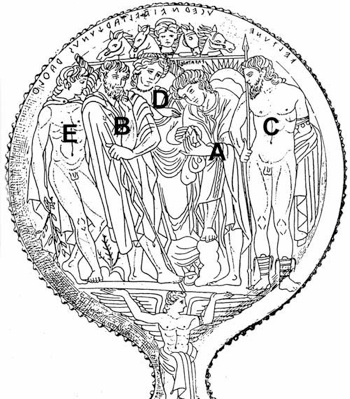

Bronze mirror (early 3rd century BC) from Tuscania

Museo Archeologico, Florence

Jean MacIntosh Turfa (referenced below, at p. 20) pointed to another singular feature of the ‘mysterious’ Etruscans:

-

“... unlike Greek and Roman practice, Etruscan religious doctrine was based on received scripture. A prophet had revealed the words of the gods, which were formally recorded and preserved by priestly, aristocratic families.”

This aspect of Etruscan culture probably accounts for the fact that (as discussed above) Etruscan literature was apparently almost entirely devoted to religion.

The earliest surviving version of this mythical revelation is preserved in a work by Cicero 0f ca. 44 BC:

-

“The tradition [relating to the origins of soothsaying] is that, once upon a time, in the district of Tarquinii, while a field was being ploughed, the ploughshare went deeper than usual and a certain Tages suddenly sprang forth and spoke to the ploughman. Now this Tages, according to the Etruscan annals, is said to have had the appearance of a boy but the wisdom of a seer. Astounded and much frightened at the sight, the rustic [ploughman] raised a great cry; a crowd gathered and, indeed, in a short time, the whole of Etruria assembled at the spot. Tages then spoke at length to his numerous listeners, who eagerly received all that he said and committed it to writing. His whole address was devoted to an exposition of haruspicina disciplina (the science of soothsaying, which the Romans referred to as Etrusca disciplina]. Later, as new facts were learned and tested by reference to the principles imparted by Tages, they were added to the original fund of knowledge. This is the story as we get it from the Etruscans themselves and as their records preserve it, and this, in their own opinion, is the origin of their [divinatory] art”, (‘De Divinatione’, 2: 23).

However, Cicero then revealed what he thought of the Etruscan lore:

-

"... do we need a Carneades or an Epicurus to refute such nonsense? Who in the world is stupid enough to believe that anybody ever ploughed up (which shall I say) a god or a man?

-

✴If a god, why did he, contrary to his nature, hide himself in the ground to be uncovered and brought to the light of day by a plough? Could not this so‑called god have delivered this art to mankind from a more exalted station?

-

✴But if this fellow Tages was a man, pray, how could he have lived covered with earth ... [and] where had he learned the things he taught others?

-

In fact, in spending so much time in refuting such stuff, I am more absurd than the very people who believe it”, (‘De Divinatione’, 2: 23).

Although this version of the myth is often taken as canonical, J. R. Wood (referenced below, at p. 237) reasonably pointed out that:

-

“Cicero himself actually warns us that his version of the myth ... is a caricature , so that his account can be interpreted as a satirical distortion ... of the original [that he found in his Etruscan sources].”

He expanded this point (at p.340) by observing that, in the light of Cicero’s concluding lines:

-

“... we must expect neither accurate report nor impartial exegesis [in the lines that precede them]. ... [Cicero] claims to be quoting [the books of the Etruscans, which were probably available in Latin by this time - see Wood’s note 18]:

-

✴I do not argue that [this claim was incorrect]: he reflects too much of the detail in ... surviving fragments [of it that were probably used by other Roman and Greek authors] not to have shared the common source.

-

✴[Rather, I argue that] Cicero has transmogrified [this ‘Roman’ original], happily tipping his polemical point with barbs of satire.”

Ovid referred to a

“... Tyrrhenian ploughman [who was astounded] when he saw a fateful clod of earth in the middle of his fields first move by itself with no one touching it and then assume the form of a man, losing its earthy nature, and opening its newly acquired mouth to utter things to come. The native people called him Tages, he who first taught the Etruscan race to reveal future events”, (‘Metamorphoses’, 15: 553-9)

Verrius Flaccus, an Augustan authority whose now-lost work was epitomised by Festus in the 2nd century AD, gave Tages’ lineage as follows:

“... Tages, [who was] the son of Genius and grandson of Jupiter, is said to have given the disciplina haruspicina to duodecim populis Etruriae (the twelve peoples of Etruria)”, (‘De significatu verborum’, 492L)

The Etruscans who later occupied these twelve cities would have been conscious of their shared ethnicity, not only because of their shared language but also because of their shared religious heritage. We know that they attributed the latter to a particular event that must have been part of a foundation myth, because their accounts of it survived into the Roman period and, although they were subsequently lost, they may well be reflected in what Nancy Thomson de Grummond (referenced below, at p. 27) described as:

-

“... a mixed lot [of surviving non-Etruscan sources, ... all of which] seem to have had access to antiquarian sources that may reflect original Etruscan writings.”

She cited, in particular:

-

✴Cicero, in a work written in ca. 44 BC;

-

✴Verrius Flaccus, an Augustan authority whose now-lost work was epitomised by Festus in the 2nd century AD; and

-

✴John Lydus, a Byzantine authority of the 6th century AD);

and reproduced the relevant texts with translations into English (used in the extracts below) in her Appendix B (at pp. 192-3, entries II: 3, II: 2 and II:5 respectively). In these, we learn:

-

✴from John Lydus (’De Ostentis’, 2: 6) that the ploughman to whom Tages appeared was none other than Tarchon, the founder of the twelve cities.

This tradition might well explain the scene depicted on the bronze mirror (early 3rd century BC) from Tuscania [Etruscan Tusena] that is illustrated above. Nancy Thomson de Grummond (referenced below, at pp. 29-30) described the scene, in which:

-

✴‘Pava Tarchies’ (A), who stands at the centre, wears a conical cap that indicates the he is a priest and stands in a ritual pose as he contemplates the liver of what was probably a sacrificed animal;

-

✴‘Avl Tarchunus’ (B), an older priest to his right, whose similar conical hat is pushed back and who watches him intently;

-

✴‘Veltune’ (C), a nude, bearded man with a spear who stands behind ‘pava tarχies’ and looks over his shoulder (at the extreme right of the composition);

-

✴‘Ucernei’ (D), a lady who stands conspicuously behind and between ‘pava tarχies’ and ‘avl tarχunus’ and reaches out towards the liver; and,

-

✴‘Rathlth’ (E), who carries a laurel branch (at the extreme left).

Nancy Thomson de Grummond (referenced below, at p. 29) observed that, although the significance of the presence of the last two figures is unclear:

-

“No better explanation has been found [for this iconography than that of Massimo Pallottino, referenced below]: we have here the myth of Tages (pava may mean puer or child, [and] tarχies could become Tages in Latin) instructing Tarchon, or perhaps his son, whose name would then be avl, in haruspicina”

I discuss the possible significance of the presence of Veltune here in my page on the Etruscan League in the Republican Period.

It seems to me that this Etruscan tradition of twelve Etruscan cities that had been founded by Tarchon and had received the Etrusca disciplina from ‘pava tarχies’ (the child Tages) might well be at the heart of the Roman construct that they subsequently entered into formal Etruscan League. However, it is important to remember that there is no surviving Etruscan evidence for the existence of such a league before the Roman conquest (which was, as we shall see, completed in 264 BC).

Putative Etruscan League in the Regal Period

Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 403) listed the references to a league of twelve Etruscan cities that can be found in the surviving sources. These include Strabo’s reference to the league before the foundation of Rome and another three that relate (or probably relate) to the Regal period.

Romulus (traditionally 753-716 BC)

By the Augustan period, the Romans believed that Romulus had founded their city and become its first king in 753 BC. According to Livy, in order to establish his new regal status in the eyes of ‘his people’, hehe:

-

“... he surrounded himself with greater state [than before] and, in particular, he appointed twelve lictors [to attend him]. Some think that he fixed upon this number [twelve] from the number of the birds who foretold his sovereignty. However, I am inclined to agree with those who think that, since the Romans ‘borrowed’ [the office of lictor], the sella curulis [seat of power] and the toga praetexta [purple-bordered toga] from their neighbours, the Etruscans, they also ‘borrowed’ the number [of lictors that Romulus chose to appoint]. Its use amongst the Etruscans is traced to the custom of the twelve sovereign cities of Etruria, when jointly electing a king furnishing him each with one lictor”, (‘History of Rome’, 1: 8: 1-3).

Tarquinus Priscus (traditionally 616-579 BC)

Dionysius of Halicarnassus first alluded to an Etruscan League in his account of the reign of King Tarquinius Priscus. Specifically, when Tarquinius had defeated a number of Latin peoples:

-

“... the rest of the Latins, becoming alarmed ... and fearing that he would subjugate the whole [Latin] nation, met together in their assembly at Ferentinum. [There, they] voted, not only to lead out their own forces from every [Latin] city, but also to solicit the aid of the strongest of the neighbouring peoples. To that end, they sent ambassadors to the Sabines and the Etruscans ... :

-

✴The Sabines promised that, as soon as they heard that the Latins had invaded Roman territory, they too would take up arms and ravage that part of Roman territory that bordered their own.

-

✴The Etruscans [also] undertook to send to their assistance whatever forces they themselves should not need. However, not all [of the Etruscan cities] were of the same mind:[ in fact], only five of them, Clusium, Arretium, Volaterrae, Rusellae and ... Vetulonia, [initially agreed to reinforce the Latins]”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 51: 3-5).

When the Romans had defeated the Latins and agreed a truce with the Sabines, the Etruscans:

-

“... passed a vote that all their cities should carry on the war jointly against the Romans, and that any city refusing to take part in the expedition should be excluded from their league”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 57: 1).

Thus, it seems that the Romans now faced an Etruscan army in which all of the members of the Etruscan League were represented. The opposing armies established their camps near Fidenae. Tarquinius:

-

“ ... laid waste and ravaged the country of the Veientines and carried off much booty. Numerous reinforcements ... from all the Etruscan cities came to aid the Veientines, [but] the Romans ... gained an incontestable victory. After this, they marched through the enemy's country, plundering it with impunity; and having taken many prisoners and much booty (for it was prosperous country) they returned home when the summer was now ending”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 57: 14).

Tarquinius then laid siege to Veii for threes years, with the Etruscans at Fidenae apparently unable or unwilling to intervene. Eventually:

-

“When he had laid waste the greater part of [Veientine] country ... , he led his army against the city of ... Caere, [which] was as flourishing and populous as any city in Etruria. A large army marched out from Caere to defend the country but ... [soon] fled back into the city”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 58: 1-2).

With the armies of both Veii and Caere contained within their own walls, Tarquinius:

-

“... led his army against the enemies in Fidenae, wishing to drive out the garrison that was there and ... to punish those who had handed over the walls to the Etruscans. ... the city was taken by storm, and the garrison, together with the rest of the Etruscan prisoners, were kept in chains under a guard. As for those of the Fidenates who appeared to have been the authors of the revolt, some were scourged and beheaded in public and others were condemned to perpetual banishment; and their possessions were distributed by lot among those Romans who were left both as colonists and as a garrison for the city”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 58: 3-4).

From this account, we can identify Veii and Caere as two more members of the Etruscan league described by Dionysius, while Fidenae was placed uncomfortably between the Etruscans and the Romans.

Dionysius now described:

-

“The last battle between the Etruscans and Romans [under Tarquinius Priscus, which] was fought near the city of Eretum in the territory of the Sabines ... This battle, the greatest of any that had yet taken place between the two nations, significantly increased the power of the Romans, who were gained a most glorious victory, for which both the Senate and people decreed a triumph to King Tarquinius. [This victory] broke the spirits of the Etruscans, who, after sending out all the forces from every city ... , received back in safety only a few. The leading men of their cities, therefore ... acted as became prudent men: when King Tarquinius led another army against them, they met in a general assembly and voted to treat with him about ending the war and they sent to him the oldest and most honoured men from each city, giving them full powers to settle the terms of peace”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 59: 1-4).

Tarquinius magnanimously received the Etruscan submission, after which:

-

“ The[Etruscan] ambassadors returned ... [to Rome], bringing the insignia of sovereignty with which they used to decorate their own kings. These were a crown of gold, an ivory throne, a sceptre with an eagle perched on its head, a purple tunic decorated with gold, and an embroidered purple robe like those the kings of Lydia and Persia used to wear, ... And, according to some historians, they also brought to Tarquinius the twelve axes, taking one from each city: for it seems to have been an Etruscan custom for each king of the several cities to be preceded by a lictor bearing an axe together with the bundle of rods, and whenever the twelve cities undertook any joint military expedition, for the twelve axes to be handed over to the one man who was invested with absolute power”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 61: 1-2).

Dionysus acknowledged that:

-

“... not all the authorities agree with those who express this opinion: some[including Livy, above] maintain that, even before the reign of Tarquinius, twelve axes were carried before the kings of Rome, and that Romulus instituted this custom as soon as he received the sovereignty. There is, however, nothing to prevent our believing that:

-

✴the Etruscans were the authors of this practice;

-

✴Romulus adopted it from them; and

-

✴the twelve axes [of the member of the defeated Etruscan League] were subsequently] brought to Tarquinius ...”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 3: 61: 3).

Servius Tullius (traditionally 579-534 BC)

According to Dionysius:

-

“After the death of Tarquinius, those [Etruscan] cities that had yielded the sovereignty to him refused to observe the terms of their treaties any longer, disdaining to submit to Tullius ... The Veientines were the leaders of this revolt; ... These having set the example, the people of Caere and Tarquinii followed it, and at last all Etruria was in arms. This war lasted for 20 years without intermission, during which time .... [the two armies] fought one pitched battle after another. But Tullius, after ... being honoured with three ... triumphs, at last prevailed ... : the twelve cities ... met [in council] once more and decided to yield the sovereignty to the Romans upon the same terms as previously. ... [Servius magnanimously] put an end to the war against them ...:

-

✴he permitted [most of the twelve cities] to retain the same government as before and also to enjoy their own possessions as long as they should abide by the treaties made with them by Tarquinius.; but

-

✴in the cases of ... Caere, Tarquinii and Veii, which had not only begun the revolt but had also induced the rest to make war upon the Romans, he ... [seized] a part of their lands, which he portioned out among those who had lately been added to the body of Roman citizens”, (‘Roman Antiquities’, 4: 27: 1-6).

Thus, we learn that Dionysius believed that there had been twelve sovereign members of the Etruscan League at the time of Tarquinius, albeit that he named only seven (Clusium, Arretium, Volaterrae, Rusellae and Vetulonia,in northern Etruria and Veii and Caere to the south

Perusia: Bishop Maximilian of Perusia attended the synods of 499, 501 and 502, all of which related to the papal schism.

Orvieto

The first known bishop of “Urbe vetere” was Bishop Giovanni, who received a stern letter from Pope Gregory I in ca. 590 (Epistle XII):

Read more:

D. Briquel, “Etruscan Origins and the Ancient Authors”, in:

J. Macintosh Turfa (Ed.), “The Etruscan World”, (2013 ) Oxford, pp. 36-55

L. Bonfante, “Etruscan Inscriptions and Etruscan Religion”, in:

N. Thomson de Grummond and E. Simon, “Religion of the Etruscans”, (2006) Texas, at pp. 9-26

S. Haynes, “Etruscan Civilisation: A Cultural History”, (2000) London

S. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X:Volume I: Book VI”, 1997 (Oxford)

L. Bonfante, “Etruscan”, in

J. T. Hooker et al., “Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet”, (1990) Berkeley and Los Angeles, at p. 321-78

The Etruscans: Main page. Etruscan League ?

Etruscan Language and Culture Early Etruscan Inscriptions Etruscan Religion

Return to the History Index