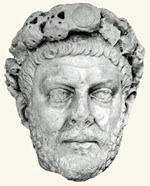

Marble bust (ca. 300 AD) of Diocletian from Nicomedia

Archeological Museum, Istanbul

Early Career

Diocletian seems to have been born to a humble family in Dalmatia in ca. 245 AD:

-

✴According to Eutropius:

-

“Diocletian, a native of Dalmatia, of such extremely obscure birth that he is said by most writers to have been the son of a clerk, but by some to have been a freedman of a senator named Anulinus” (‘Breviarium historiae Romanae’, 19:2).

-

✴According to the ‘Epitome de Caesaribus’:

-

“Diocletian, a Dalmatian, freedman of the senator Anulinus, was, until he assumed power, called in their language Diocles, from his mother and likewise from a city named Dioclea; when he took control of the Roman world, in the fashion of the Romans, he converted the Greek name” (39:1).

Since Diocletian’s only child, his daughter Valeria, married in or shortly before 293 AD, he probably married his wife Prisca (Valeria’s mother) in ca. 275 AD.

Zonaras described Diocletian’s rise through the ranks of the imperial army:

-

“[Diocletian] ... was Dalmatian by birth, of undistinguished parentage, and some say an emancipated slave of the senator Anulinus, becoming dux of [Moesia] from the rank of simple soldier. Still others say he became the commander of the imperial bodyguard [comitem domesticorum] ... (‘Epitome Ton Istorion’ 12:31)”

Diocletian had reached his position in the imperial bodyguard by the time of the Emperor Carus’s march into Persia in 283 AD. This was an extraordinarily important campaign, designed to avenge the humiliation that the Persians had inflicted on the Emperor Valerian in 260 AD. The tumultuous events that surrounded it determined Diocletian’s future career.

Acclamation

Death of Numerian (284 AD)

After early success against the Persians, Carus suddenly died (apparently struck by lightening), and the army acclaimed his son, the erstwhile Caesar Numerian, as Augustus. Numerian now ruled jointly with his older brother, Carinus, whom Carus had designated as his co-Augustus and who had been looking after the affairs of the Empire while his father campaigned in the east. Carinus and Numerian jointly assumed the Consulship for 284 AD.

According to Zonaras:

-

“When [Carus] had died ... his son Numerianus was left behind as the only Emperor in the camp. He immediately marched off against the Persians and battle broke out in which the Persians gained the upper hand and the Romans were turned to flight” (‘Epitome Ton Istorion’ 12:27).

This is the only surviving account of a defeat inflicted on Numerian’s army at the hands of the Persians. (Aurelius Victor, for example, portrayed his withdrawal as a matter of choice in the extract below). Subsequent events suggest that Zonaras might well have been correct, and that the army was extremely unhappy about the perceived failure of Numerian and Aper. Aurelius Victor described these subsequent events in two separate sections:

-

-“Numerian, after losing his father, at the same time decided that the war was over, but while he was leading his army back he was murdered through the treachery of Aper, [who was both] the Praetorian Prefect and his father-in-law. ... the deed was concealed for a long time, ... . But, after the crime had been betrayed by the odour of his decomposing limbs, at a council of generals and tribunes, Valerius Diocletianus, commander of the household troops [domesticos regens], was [acclaimed as Numerian’s successor] because of his good sense ...” (‘De Caesaribus’, 38:5 - 39:1).

-

- “[Diocletian], in his first speech to the army, drew his sword, gazed at the sun and, while attesting that he had no knowledge of Numerian’s murder and that he had not wanted the imperial power, transfixed Aper, who was standing beside him, with one blow. It had been through his treachery ... that [Numerian] had perished” (‘De Caesaribus’, 39:9).

David Potter (referenced below, 2013, at p 27) absolved Diocletian from the charge of having murdered Aper on the grounds that:

-

“... it seems unlikely that [Lactantius] would omit a tale that [Diocletian, whom he despised] began his reign in a fit of homicidal fury”.

However, Pierfrancesco Porena (referenced below) countered this view by pointing out that there must have been a large number of eye witnesses to such a public act.

The discovery of the death of Numerian and the consequent acclamation of Diocletian can be securely dated to 20th November 284 AD:

-

✴Lactantius (‘De Mortibus Persecutorum’ , 17:1) specified Diocletian’s dies natalis, the anniversary of his acclamation, as “the twelfth of the kalends of December” (20th November); and

-

✴Pierfranceso Porena (referenced below, at p 24, note 3) cited supporting evidence for this from an Egyptian papyrus (which allowed alternative dates in early chronicles to be ignored).

The Paschal Chronicle recorded that Diocletian designated himself and a colleague Bassus (below) as Consul for the rest of the 284 AD. By this act, he signalled that he no longer recognised the imperium of Carinus: conflict between them was inevitable.

Victory over Carinus (285 AD)

Carinus first had to deal with the usurper Julianus, or possibly with two usurpers of the same name.

-

✴According to Aurelius Victor:

-

“[When Carinus heard of the death of Numerian], he made for Illyricum by skirting Italy. There, he scattered Julianus’ battle line and cut him down. For [Julianus] while he was governing the Veneti as corrector, had learned of Carus’ death and in his eagerness to seize the imperial power, he had advanced to meet the approaching enemy” (‘De Caesaribus’, 39:6).

-

This usurper was presumably the Emperor Marcus Aurelius Julianus, for whom coins were minted in 284-5 AD at Siscia:

-

-one issue had the reverse legend ‘PANNONIAE AVG’ (Augustus of Pannonia); and

-

-two issues had the reverse legend ‘VICTORIA AVG’ (victorious Augustus).

-

As noted below, these victories were presumably secured against barbarian invaders on the Danube.

-

✴Zosimus (‘Historia Nova’, 1:73:1-3) described the usurpation of the Praetorian Prefect, Sabinus Julianus. This part of his account is not readily accessible, since it was missing from the manuscript that is most usually translated into English. However, Pierfrancesco Porena (referenced below) published the original Greek (at p 40) and summarised it in Italian. According to this account, when the news of Numerian’s death reached Italy, the officers of the legions stationed in Italy proclaimed Sabinus Julianus, Carinus’ Praetorian Prefect, as Augustus. As the only other early source that mentioned Sabinus Julianus (albeit without specifying his office) recorded:

-

“Then Sabinus Julianus, who took power, was killed by Carinus in campis Veronensibus [a location near modern Verona]” (‘Epitome de Caesaribus’ 38: 6).

Many scholars believe that Sabinus Julianus and Marcus Aurelian Julianus were the same person (see, for example, the paper by Bill Leadbetter referenced below). However, Pierfanceso Porena presented a reasoned account for his assertion that the accounts by Aurelius Victor on the one hand and Zosimus and the anonymous author of the ‘Epitome de Caesaribus’ on the other relate to two usurpers, whose revolts were separated in time and place.

-

✴He suggested that the account of Aurelius Victor (above) should be understood to start chronologically with its third sentence: Julian of Pannonia, who was acclaimed as Augustus shortly after the death of Carus in 293 AD, demonstrated his new power by marching against a barbarian incursion (“the advancing enemy”). Having claimed victory against them, he minted accordingly (above). Carinus had been in no hurry to interrupt Julianus’ offensive against the barbarians: however, when he heard of Numerian’s death (probably in December 284 AD), he duly marched from Gaul into Pannonia and defeated him.

-

✴Meanwhile, his erstwhile Praetorian Prefect, Sabinus Julianus had been acclaimed as Augustus by the legions based in northern Italy. Carinus duly marched south towards Verona, where he defeated and killed this second usurper. This battle was remembered in a panegyric (Panegyric XII, translated into English in Nixon and Rodgers, referenced below) that was delivered at the court of the Emperor Constantine in Trier in 313 AD: in a passage devoted to Constantine’s defeat of Maxentius’ army at Verona in 312 AD, the panegyrist referred to:

-

“... that miserable town, Verona, already stained by citizens’ blood in our middle age ...” (8:1).

-

The translator (at note 54) explained that this must had referred to the middle age of the panegyrist and to Carinus’ defeat of Julianus in 285 AD.

After these victories, Carinus was finally in a position to confront the more formidable challenge from Diocletian, who was marching west towards Pannonia. According to Aurelius Victor:

-

“When Carinus reached Moesia, he straightway joined battle with Diocletian near the Magus [River, near modern Belgrade], but while he was in hot pursuit of his defeated foes, he died under the blows of his own men ....That was the end of Carus and his children [Carinus and Numerian]” (‘De Caesaribus’, 39:12).

With the murder of Carinus, Diocletian became the last Augustus standing, and it is reasonable to assume that Carinus’ army accepted him as such. Timothy Barnes (referenced below, 1982, at p 50) dated these events to the spring of 285 AD. According the Aurelius Victor:

-

“Pardon was granted to ... practically all [of the former supporters of Numerian and Carinus], especially one outstanding man named Aristobulus, the Praetorian Prefect, on account of his services. This was a novel and unexpected occurrence ... that in a civil war no-one was stripped of his possessions, reputation or rank” (39: 14-5).

David Potter (referenced below, 2013, at p 27) observed that Diocletian triumphed over Carinus:

-

“... amid a welter of betrayal and deceit”.

In particular, he implicated Aristobulus, who had held the Consulship with Carinus in 285 AD: he retained the post of Praetorian Prefect under Diocletian finished his Consulship, with Diocletian replacing Carinus as his colleague (see below).

Nomenclature

The way in which Diocletian’s name evolved at the time of his acclamation can be followed to some extent:

-

✴According to Lactantius (‘De Mortibus Persecutorum’, 9.11) he was called Diocles “before his reign”. This might have been the source of the information in the ‘Epitome de Caesaribus’ (above), which added that the name derived “from his mother and likewise from a city named Dioclea [probably Doclea, modern Montenegro]”.

-

✴Timothy Barnes (referenced below, 1982, p 31) noted that he was named as Diocles in an Egyptian papyrus of 7th March 285 AD (i.e. after his initial acclamation as Augustus in November 284 AD but before his victory over Carinus in the following year). Nenad Cambi (referenced below) expands this by recording the name in this source (referenced as P. Oxy. XLII 3055) should be transcribed as Gaius Valerius Diocles.

-

✴By the time of his first coins struck for him in Rome shortly thereafter, the name Diocles had been Latinised to Diocletianus.

Nenad Cambi (referenced below) deduced that Diocletian’s original name must have been Diocletius, and suggested that he had adopted the Greek form when he enlisted in the army. Cambi also suggested a way in which Diocletian might have acquired the praenomen Gaius and the cognomen Valerius: since the “Epitome De Caesaribus” (above) asserts that he was “a freedman of the senator Anulinus”, it could be that ‘Gaius Valerius’ had been Anulinus’ praenomen and cognomen. However, all that can be said with certainty is that Diocletian inherited or acquired (whether by accident or design) a cognomen that harked back to the gens Valeria, one of the most ancient and most celebrated families of Rome.

Diocletian’s Praetorian Prefects

It is clear that Carus had appointed a college of two Praetorian Prefects:

-

✴Aper, who had travelled with Carus himself on the Persian campaign and who had continued in this office under Numerian (who was his son-in-law) after Carus’ death; and

-

✴Aurelius Aristobulus (above), who had served Carinus in the west, and who might have replaced Sabinus Julianus (above) in this post in late 284 AD.

Diocletian certainly followed the policy of appointing two Praetorian Prefects from ca. 286 AD (as discussed on the following page). he might well have done so before:

-

✴It seems reasonable to assume that, following his acclamation and the execution of Aper in November 284 AD, he appointed his first Praetorian Prefect. An argument is made on the following page that this might well have been Afranius Hannibalianus.

-

✴We know from Aurelius Victor (above) that Aurelius Aristobulus continued in office under Diocletian, following the murder of Carinus in the summer of 285 AD. If the hypothesis regarding Afranius Hannibalianus is correct, then he and Aurelius Aristobulus probably served in the east and west (respectively) thereafter.

Diocletian and Rome

Zonaras recorded that, after he had been acclaimed by the army following the death of Numerian in 294 AD (and presumably after his subsequent death of Carinus in the following year), Diocletian travelled to Italy:

-

“On reaching Rome, he laid claim to and came into the management of the affairs of the Empire” (‘Epitome Ton Istorion’, 12:31).

This is the only record of this visit to Rome, but a coin (RIC V:II 203) that was minted for Diocletian at Ticinum (Pavia, near Milan) at about this time had the reverse legend ‘ADVENTUS AUG’. Thus the newly victorious Diocletian certainly made a ceremonial entry into Milan. It seems likely that he then received the endorsement of the Senate, either at Milan or during a subsequent and brief visit to Rome.

As noted above, Diocletian made new consular designations after his acclamation in November 284 AD: he named himself as Consul for the rest of the year and chose as his colleague a man called Bassus. Timothy Barnes (referenced below, 1982, at p 97) identified him as the magnificently named Lucius Caesonius Ovinius Manlius Rufinianus Bassus, an eminent Senator who might well have been present at Numerian’s entourage. He is commemorated in an inscription (AE 1964, 223; LSA-2579) from Naples that gives a detailed description of his career. In addition to a number of prestigious priesthoods, he held the following important offices:

-

✴“Divus Probus” - i.e. the Emperor Probus (276-82 AD) - had appointed him as the President of what was probably a senatorial court of appeal in Rome.

-

✴He was subsequently “comes” to a pair of Augusti, presumably Carus/ Numerian and Carinus in 283-4 AD.

-

✴He served as Consul twice and as Prefect of Rome.

Bassus clearly held the senior posts attributed to him after the death of Probus in 282 AD. However, he does not appear in official lists of Consuls and Urban Prefects. Timothy Barnes (referenced below, 1982, at p 112), who analysed the lacunae in the surviving records, suggested that:

-

“If Bassus was Consul for the second time with Diocletian for the last weeks of 284 AD [as suggested above], then he presumably [became] prefect of [Rome] after Carinus was defeated and killed in the spring of 285 AD.”

Bassus would certainly have been eminently well-placed to facilitate Diocletian’s acceptance by and good relations with the Senate at this critical early phase of his rule.

There is no surviving record of Bassus’ subsequent career, and it is possible that he was already old at the time of his second Consulship. Junius Maximus replaced him as Urban Prefect in ca. February 286 AD, and held the post for the next two years, together with the Consulship of 286 AD. Another person who might well have been active in Rome on Diocletian’s behalf was Aurelius Aristobulus (above), the second Praetorian Prefect and the Consul (with Diocletian) of 285 AD.

Border Security

The civil war that had convulsed the Empire in 284-5 AD had the expected effect of inciting barbarian incursions in the frontier regions. As Bill Leadbetter (referenced below, at p 51) observed:

-

“Whereas, scant years before, [the Emperor Probus (276-82 AD)] could boast that a minimal number of soldiers were needed to maintain the [imperial] borders, ... by 285 AD soldiers in arms were needed everywhere”.

Diocletian soon left Italy for the frontier on the Danube, which presumably demanded his immediate attention. However, before his departure, he had to put in place measures to secure his position in Gaul. According to Aurelius Victor:

-

“... after Carinus’ death, [Aelianus] and Amandus had stirred up a band of peasants and robbers in Gaul, whom the inhabitants call Bagaudae, and had ravaged the regions far and wide and were making attempts on very many of the cities. [When Diocletian heard of this], he immediately appointed as Emperor (imperatorem iubet) Maximian, a loyal friend who, although he was rather uncivilised, was nevertheless a good soldier of sound character” (‘De Caesaribus’ 39:12).

A panegyric (Panegyric X, translated into English in Nixon and Rodgers, referenced below, which was delivered at Maximian’s court, probably at Trier and probably in 289 AD) similarly described the Bagaudae as:

-

“... inexperienced farmers [who] sought military garb; the ploughman imitated the infantryman, the shepherd the cavalryman, the rustic ravager of his own crops the barbarian enemy” (4.3).

These descriptions of a couple of rebels leading a peasant rabble might well be misleading: for example, David Potter (referenced below, 2004/14, at p 277) suggested, the Bagaudae more probably belonged to armed militia that survived from the days of the independent Gallic Empire (260-74 AD). They may well have supported Carus and his sons (who had originated at Narbo, modern Narbonne, in southern Gaul) and were thus natural opponents of Diocletian. Whether or not this was the case, the allegation that the rebels were gratuitously causing mayhem might well be misleading. It is surely more likely that their leaders had mobilised them to deal with barbarian incursions following Carinus’ departure, and that they had taken the opportunity to claim imperium on the tradition established by the rulers of the secessionist Gallic Empire of 260-74 AD.

There is numismatic evidence that secession was exactly what the leaders of the revolt had in mind: Percy Webb (referenced below, at p 579) discussed a number of coins that were apparently minted at this time commemorating Quintus Valens Aelianus and Gaius (or Silvius) Amandus as Augusti. If authentic, these coins would suggest that Aelianus and Amandus were indeed following in the footsteps of the earlier Gallic Emperors, all of whom had minted coins in the Roman manner. Actually, Webb:

-

✴dismissed those ascribed to Aelianus as probable fakes; and

-

✴noted doubts about some of those ascribed to Amandus.

However, he catalogued three of the latter (at p 595), and commented (at p 579) on one in particular that he had been able to examine in detail:

-

“[This] coin does not bear any palpable traces of alteration and, while ... it must be accepted with reserve [because of its extreme rarity], it cannot be disregarded”.

If at least some of the coins minted for Amandus were genuine, he had presumably been acclaimed as Augustus by an army.

The severity of the crisis in Gaul is most eloquently demonstrated by the fact that Diocletian took the momentous step of appointing Maximian, to whom he was unrelated, as his imperial colleague in order to deal with it.

Read more:

‘RIC’ - see Webb (1933) below

D. Potter, “Constantine:the Emperor”, (2013) Oxford

W. Leadbetter, “Galerius and the Will of Diocletian”, (2009) London

N. Cambi, “Tetrarchic Practice in Name Giving”, in

A. Demandt and A. Goltz (Eds), “Diokletian und die Tetrarchi: Aspekte einer Zeitenwende”, (2004) Berlin, pp 38-46

D. Potter, “The Roman Empire at Bay, 180–395 AD”, (2004, second edition 2014) Abingdon

P. Porena, “Le Origini della Prefettura del Pretorio Tardoantica”, (2003) Rome

C. E. V. Nixon and B. S. Rodgers, “In Praise of Later Roman Emperors: The Panegyrici Latini”, (1994) Berkeley

T. Barnes, “New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine”, (1982) Harvard

P. Webb, “The Roman Imperial Coinage: Volume 5:2”, (1933) London

Diocletian (284-305 AD):

Diocletian's Rise to Power (284-5 AD) Diocletian and Maximian (285-93 AD)

First Tetrarchy (293-305 AD) Diocletian, Maximian and Rome (285-305 AD)

Military Campaigns: Maximian and Constantius in the West (293-305 AD)

Military Campaigns: Diocletian and Galerius in the East (293-305 AD)

Imperial Cult (285-305 AD)

Diocletian to Constantine (285-337 AD): Literary Sources

Return to the History Index