Revolt in Etruria (36 BC)

Perusia seems to have been the only Etruscan city that rebelled against Octavian in 41 BC, although this short but bloody war convulsed the Valle Umbra. After the fall of Perusia in the following spring, the city burned down and, although its surviving citizens were allowed to return, they suffered the confiscation of almost all of their land outside the city walls. The bad feeling left by these events would have been exacerbated by the actions of Sextus Pompeius (the son of Pompey the Great), who was securely based on Sicily and who was able to use his formidable naval capability to disrupt the Italian grain supply. Octavian’s attempted invasion of Sicily in 38 BC failed spectacularly (see below), and he was not able to assemble a fleet for a second attempt until July 36 BC. Even then, he faced further setbacks (described below), before he secured a definitive victory off Naulochus in September 36 BC.

Our sources indicate two distinct episodes of violence in Etruria at this time:

-

✴According to Cassius Dio, during Octavian’s absence from peninsular Italy in 36 BC:

-

“... parts of Etruria ... had been in rebellion, [but they] become quiet as soon as word came of his victory [at Naulochus]” (‘Roman History’, 49: 15: 1).

-

✴According to Appian, even after the victory:

-

“... Italy and Rome itself were openly infested with bands of robbers, whose doings were more like barefaced plunder than secret theft. Octavian appointed [Caius Calvisius] Sabinus to correct this disorder. He [Sabinus] executed many of the captured brigands and, within one year, brought about a condition of absolute security” (‘Civil Wars’, 5:132).

Thus, Emilio Gabba (referenced below, at p. 100) summarised:

-

“Still in 36 BC, the entire area of Etruria was in revolt, and Octavian had to entrust ... Sabinus with the task of wiping out the armed bands that still roamed across central Italy” (my translation).

Octavian made unusual arrangements for the administration of peninsular Italy in his absence during his second war with Sextus. According to Cassius Dio:

-

“Other matters in [Rome] and in the rest of Italy were administered by one Gaius Maecenas [see below], a knight, both then [i.e. in July - November 36 BC] and for a long time afterwards” (‘Roman History’, 49: 16:2).

Josiah Osgood (referenced below, at p. 323) explained the significance of this appointment:

-

“... when, in 36 BC, after Octavian’s departure from Rome, disturbances broke out, both there and in Etruria (site of the earlier Perusine War), [Octavian] ... gave Maecenas, [who was] not even of senatorial rank, police powers to settle the situation.”

The situation seems to have played out in stages, governed by the progress of the war. Appian recorded that, when Octavian’s fleet was damaged in a storm early in the campaign:

-

“In anticipation of more serious misfortune, [Octavian] sent Maecenas to Rome on account of those who were still under the spell of the memory of Pompey the Great, for the fame of that man had not yet lost its influence over them” (‘Civil Wars’, 5:99).

According to A. J. M. Watson (referenced below, at p. 99):

-

“... it seems that [this] was more of a diplomatic mission than one with a military purpose; ... because the populace in Rome began to riot, Maecenas, Octavian's principal diplomat, was sent to Rome to mollify them.”

When Octavian suffered a more serious setback off Mylae in August, Appian recorded that:

-

“He sent Maecenas again to Rome on account of the revolutionists; and some of these, who were stirring up disorder, were punished (‘Civil Wars’, 5:112).

A. J. M. Watson (referenced below, at p. 99) suggested that:

-

“The tenure of [Maecenas’] administration [of Rome and Italy] really began in mid-August, with the naval defeat ... off Mylae. As a result of this [defeat], a rebellion began in Etruria [as recorded by Cassius Dio, above] and Octavian gave Maecenas control of Rome and Italy, [with orders] to keep Rome loyal and to [suppress] the [Etrurian] rebellion ... However, before he could deal with [the latter], there was [another] outburst of unrest in Rome ... [which became] Maecenas' first objective ...”

Putting these accounts and interpretations together, we might reasonably assume that the revolt in Etruria broke out in August 36 BC and that Maecenas, who was tied up in Rome, delegated the task of suppressing it, probably to Sabinus (although no surviving source actually identifies him at this point). Sabinus’ task was made much easier by the news of the victory at Naulochus, which brought an end to the famine and simultaneously removed any hope that the rebels might have had of a rival to Octavian in the west. Thereafter, Sabinus turned his attention to the lawlessness that still engulfed the region (which might be a euphemism for a programme of reprisals against the former rebels).

It would a mistake, in my view, to regard this short revolt in Etruria as an isolated event. Ronald Syme (referenced below, 1939, at p. 208) wrote of the Perusine War that it:

-

“... blended with an older feud and took on the colours of an ancient wrong. Political contests at Rome and the civil wars into which they degenerated had been fought at the expense of Italy [for decades]. Denied justice and liberty, Italy rose against Rome for [almost] the last time.”

In my view, the revolt in Etruria in 36 BC represented a final postscript to an incipient rebellion in central Italy (and elsewhere on the peninsular) that had occupied much of the century.

William Harris (referenced below, at p 313-4) suggested (without giving his sources) that:

-

“Of the more important towns of Etruria, only Tarquinii, Volsinii and Clusium may have survived the triumvirs and Augustus fairly untroubled.”

However, there is evidence (discussed below) for extensive imperial land-holdings around Volsinii the imperial period, and it is possible that the land in question had been confiscated after the revolt of 36 BC.

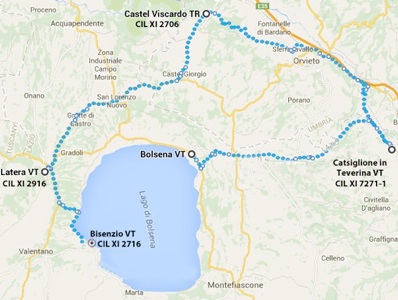

An Imperial Estate near Volsinii ?

Find spots of inscriptions suggesting an imperial estate north of Bolsena

(The routes marked by blue dots are the existing roads between the various marked locations)

Francis Tassaux (referenced below, at pp. 557-60) recorded five inscriptions (all dated after the period discussed here) from the area to the north of Bolsena that might indicate the existence of an imperial estate:

-

✴Two of these, which date to the reign of Augustus (as the triumvir Octavian became in 27 BC), were found by a farmer in Santa Maria in Paterno, Castiglione in Teverina:

-

•AE 1904, 0194 commemorated Germanus, a freedman of Augustus and procurator, who had financed the building of a Caesarium and its decoration:

-

Germanus Aug(usti) / lib(ertus) proc(urator)

-

Caesareum fec(i)t / et omni cul/tu exornavit

-

•AE 1904, 0195 commemorated Epaphroditus and Hyacinthus (each of whom was also a freedman of Augustus and procurator) who had restored a shrine dedicated to Apollo Augustus that had apparently fallen into disrepair:

-

Apollini Aug(usto) Epaphro[ditus Aug(usti) lib(ertus) proc(urator)]

-

Apollini Aug(usto) Hyacinthus Aug(usti) lib(ertus) p[roc(urator)

-

aediculam vetustate]/ delapsam(!) sua pecunia [refecit]

-

The cult site evidenced by the these two inscriptions, which seems to have comprised a Caesarium and a temple of Apollo Augusto, might have been built early in the imperial period: Octavian, who regarded Apollo as his personal patron, dedicated a new temple of Apollo near his palace on the Palatine in 28 BC. The involvement of freedmen of Augustus suggest that this cult site at Castiglione in Teverina was on an imperial estate and served a private rather than a municipal cult (as noted by Ittai Gradel, referenced below, at p. 83). It is possible that the Caesarium was devoted to Augustus himself (as Gradel assumed), although it is also possible that it was devoted to divus Julius (as suggested, for example, by Stefan Weinstock, referenced below, p. 407, note 4).

-

✴The other three inscriptions cover a period from the reign of the Emperor Tiberius to that of the Emperor Trajan (i.e. 14 - 114 AD:

-

•An inscription (CIL XI 2916) from Latera reads:

-

Chryseros Ti(berii) Caesaris Drusianus, vil(icus ??)

-

The possible completion “vilicus” suggests that Chryseros was a slave charged with the management of a villa in this area owned by Tiberius and/or his son, Drusus Julius Caesar (died 23 AD).

-

•A double-sided inscription (CIL XI 2716) from Visentium (Bisenzio, across the lake from Bolsena), reads:

-

Neronis Caesaris Aug(usti)

-

This suggests that the nearby land belonged to the Emperor Nero (54-68 AD).

-

•The inscription (CIL XI 2706) from Castel Viscardo (discussed in page - link) commemorates a freed slave, Ulpiae Terpsidi, the well-deserving wife of Securus and pious mother of Hilarus. Securus (who was still a slave) held the post of imperial dispensator (treasurer). Francis Tassaux (referenced below, at p. 558, note 71) suggested that:

-

“... in all likelihood [Ulpiae] had been a freed woman of the Emperor Trajan [98-117 AD]” (my translation).

As Tassaux observed (at p. 558):

-

“Certainly a mere inscription of an imperial slave or freedman is not sufficient to prove the existence of an imperial property. However, the concentration of [these] five testimonies in three specific locations around Bolsena (on the one hand on the shore of Bisentium, and on the other hand on the main axis of the [Via] Traiana Nova), which relate to a dispensator, a possible procurator, a possible vilicus and a possible imperial workshop, ... make such a hypothesis likely” (my translation).

It is, of course, possible that these lands were accumulated over a long period and, indeed, that they never formed a single estate. However, it is tempting to postulate the origins of this imperial land-holding in the revolt discussed above.

After Naulochus (36 BC)

Octavian became the most powerful man in the western part of the Empire after Naulochus. He had spent the period since the murder of his ‘father’, Julius Caesar, in 44 BC in a desperate struggle to share power with Mark Antony, and, in the process, had hardly endeared himself to the people of Italy. However, as Josiah Osgood (referenced below, at p.300) observed,:

-

“Everything changed so suddenly [after Naulochus]. There was now only Antony [in the east] and Octavian. Maybe, as Octavian announced, there would be an end to civil wars.”

Osgood referred here to the following passage from Appian:

-

“When [the victorious Octavian] arrived at Rome [in November, 36 BC], the Senate voted him unbounded honours ... The next day he made speeches to the Senate and to the people .... He proclaimed peace and goodwill, said that the interviews [relating to proscriptions] were ended, remitted the unpaid taxes, and released the [tax] farmers ... and the holders of public leases from what they owed. Of the honours voted to him, he accepted ... [inter alia] a golden image to be erected in the forum ... to stand on a column covered with the beaks of captured ships. There the image was placed, bearing the inscription:

-

‘PEACE, LONG DISTURBED, HE RE-ESTABLISHED ON LAND AND SEA’

-

... This seemed to be the end of the civil dissensions. Octavian was now 28 years of age. Cities joined in placing him among their tutelary gods.” (‘Civil Wars’, 5:130 -2).

Octavian now seems to have embarked on a carefully planned propaganda programme. Josiah Osgood (referenced below, at pp.323-4) commented on his:

-

“... new persona after Naulochus, ...[which represented the] most significant of several shifts in [his] public image during the triumvirate. ... Now, he would try to ... [repair his image among] the segment of [Italian] society that [he] had antagonised terribly with land confiscations and dissatisfied still further with the war against Sextus... [He now wanted] to show that there would be an end to chaos, that ... property rights did matter. [Among the measures he took with this in mind, he started] dealing with the gangs of bandits that had seized on civil war as an opportunity to menace the Italian countryside. ... In 36 BC, [he] appointed ... Calvisius Sabinus to crush the outlaws, a task that he [carried out] with notable success ...”

Osgood acknowledged that:

-

“The record that we have in our sources must surely be an echo of Octavian’s own advertisement of this crackdown on crime.”

In my view, Octavian probably elided the categories of rebels (i.e. political enemies) and criminals. Whether or not this was the case, any reprisals against the former were probably minimal, and they certainly did not face the prospect of further veteran settlement on their land: as Josiah Osgood (referenced below, at p. 324) pointed out:

-

“This time, ... there was no need for dispossessed landowners [in Italy] to take up arms. To settle the 20,000 time-served men who had been fighting at least since the battle of Mutina [of 43 BC], Octavian .... used public land ... and some plots abandoned in the colonies of 41 BC, ... [while] other veterans were sent [outside Italy], especially to Gaul, a province [now] in his control.”

As noted above, we do not know whether Volsinii had been a centre of the rebellion. However, whether or not this had been the case, its status as the last Etruscan city to have withstood the original advance of Rome and its ownership of the ex-federal Etruscan sanctuary would surely have made it an attractive centre for any programme of the pacification of Etruria thereafter. Further, we might expect that the famously Etruscan Maecenas would have played a prominent role in any such programme.

Maecenas

According to John Hall (referenced below, at pp. 168-9), Etruscans featured prominently among Octavian’s early supporters, and:

-

“Approximately [six] of these could be counted among his closest and most influential advisors, with Agrippa and Maecenas ultimately rising to occupy positions of great authority ...”

While there is no evidence (as far as I am aware) that Agrippa, who came from Pisa, attached particular importance to what might have been considered his Etruscan roots, the case of Maecenas, who came from Arretium (Arezzo), is very different. Stephen Oakley (referenced below, at p. 68) summarised the evidence for his pride in his Etruscan roots:

-

“... Tacitus (‘Annals’, 6:11:2) refers to him as Cilnius Maecenas. ... it is clear that [the equestrian Maecenas] must have been closely related to the [noble and ancient Aretine family of the] Cilnii, and it is often argued that his mother was a Cilnia. On several occasions, poets refer to [his] descent from [Etruscan] princes ...”

Thus, Propertius referred to:

-

“Maecenas, Etruscan eques (knight) of royal blood, keen not to rise above your rank ...” (‘Elegies’ 3.9).

Maecenas could thus claim among his ancestors men who had presided over the annual meetings of original Etruscan Federation, as lucumones (kings of the 12 Etruscan city states) or sacerdotes (the priests who replaced them in this capacity after the regal period. Any thoughts of reviving the federation would have been premature at this early stage in Octavian’s career. However, we might reasonably assume that Maecenas would already have appreciated the propaganda value of any measure that associated Octavian with the ex-federal sanctuary.

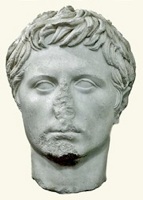

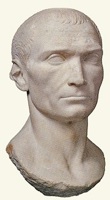

Caius Calvisius Sabinus and a Volsinian Bust of Octavian

Constantine I, recut from a bust of Octavian Octavian C. Calvisius Sabinus

From the “basilica forense” of Volsinii Both from the Roman theatre, Spoleto

Museo Nazionale Etrusco, Viterbo Both in Museo Archeologico, Spoleto

Sabinus was famously one of only two senators who had tried to defend Octavian’s ‘father’, Julius Caesar, when he was murdered in 44 BC. By the time of the Etruscan revolt, he was an active supporter of Octavian himself. He served as consul of 39 BC and then as the admiral of Octavian’s fleet. Together with Menodorus, who had defected from Sextus to Octavian in 39 BC, he assembled one of the two fleets with which Octavian intended to invade Sicily in 38 BC. Sabinus and Menodorus duly set sail from Etruria, but were intercepted before they could join up with the second fleet, which was under Octavian’s command, and which suffered an outright defeat. Soon after, what remained of both of fleets was destroyed in a storm. Thus ended the disaster of 38 BC that was mentioned above. When Menodorus subsequently deserted again, this time back to Sextus, Octavian relieved Sabinus of his naval responsibilities and appointed Agrippa in his place. We next hear of Sabinus after what was, in effect, Agrippa’s victory at Naulochus: as we have seen, he was charged with the eradication of banditry in Etruria after the victory.

I suggested above that Maecenas might well have delegated to him the suppression of the revolt that had probably broken out in the previous month. Whether or not this was the case, he certainly undertook a police operation in the region (discussed above), and there is circumstantial evidence that he participated in the subsequent programme designed to reconcile the Etruscans with their erstwhile oppressor. This is in the form of bust of Octavian, which was re-cut in ca. 315 AD to represent the Emperor Constantine I (illustrated to the left, above), and which was discovered during excavations of a basilica that stood in the forum of Volsinii (now the archeological area at Poggio Moscini, Bolsena). According to Annarena Ambrogi and Ida Caruso (referenced below, 2012 and 2013), the original bust of Octavian had been of the so-called Béziers-Spoleto type, which is among the earliest known representations of Octavian, and which Dietrich Boschung (referenced below, at pp. 25-26 and pp. 59-62) dated to 43-40 BC.

The Spoletan version of this bust (illustrated above, at the centre) was found during the excavation of the theatre of Spoleto, near a broadly contemporary bust that almost certainly represents Sabinus (illustrated above, on the right), who (in addition to his posts under Octavian described above) was the patron of Spoleto. Spoleto seems to have supported the rebels during the Perusine War but, as Emilio Gabba (referenced below, at p. 102) pointed out, it escaped serious reprisals thereafter (apart from the transfer of the sanctuary at the source of the Clitumnus to Octavian’s new colony at Hispellum). Gabba suggested that Spoletium had fared so well because of Sabinus’ patronage. It seems likely (at least to me) that Sabinus commissioned both:

-

✴the Spoletan bust of Octavian, as part of a programme of reconciliation after the Perusine War; and

-

✴the Volsinian bust of Octavian, this time as part of a programme (perhaps directed by Maecenas) to consolidate Octavian’s position in Etruria after the revolt there and in the euphoria that followed the victory at Naulochus.

The original location of the bust in Volsinii is a matter for conjecture:

-

✴As already noted, the Spoletan prototype was found in the Roman theatre there: the similar head from Volsinii might also have been in a theatre, assuming that a permanent theatre existed in the city at this time. (As noted below , an inscription, which was found in 1536 on the site of the original forum, records the names of the four magistrates who had financed the construction of a “theatre and proscenium” in the late 1st century BC) .

-

✴Another possibility is that the statue was originally in the putative Temple of Nortia at Campo della Fiera (as discussed in my page on the Sanctuary at Campo della Fiera in the Triumviral and Augustan Periods).

Emperor Augustus (27 BC - 14 AD)

Political Climate after Actium

Octavian defeated Mark Antony at the Battles of Actium (31 BC) and Alexandria (30 BC). The promised end to the civil wars, which had been somewhat prematurely declared after Naulochus, was now a reality. Italy could now look forward to the fruits of his victories in a period of peace, security and prosperity: the acceptance of what was, in effect, a dictatorship must have seemed a small price to pay. Octavian celebrated a triple triumph (for victories at Actium and Alexandria and in Dalmatia) in 29 BC.

His first problem was to settle the affairs of the army. Ronald Syme (referenced below, 1939, at p. 34) observed that, after Actium:

-

“... the armies of Rome presented a greater danger to [the stability of the Empire] than did any foreign enemy. ... [Octavian], who had seduced, in turn, the armies of all of his adversaries, found himself in the embarrassing possession of nearly 70 legions. For the military needs of the Empire, fewer than 30 would be ample: any larger total was costly to maintain and a menace to internal peace. He seems to have decided on a permanent establishment of about 26. The remainder were disbanded, the veterans being settled in colonies in Italy and the provinces.”

However, the brutal and indiscriminate confiscations of 41 BC were not needed on this occasion: as Syme continued:

-

“The [necessary land was supplied by confiscation from ... the towns and partisans [of the defeated Mark Antony] in Italy, or purchased from the war booty, especially the treasure of Egypt. Liberty was gone, but property, respected and secure, mounted in valuewas now mounting in value. The beneficial working of the rich treasure from Egypt became everywhere apparent.”

Octavian then began the process of creating a form of government within which he could wield total power without the appearance of doing so. In 27 BC, he accepted from the Senate the unprecedented title of Augustus.

Lucius Caecina

A now-lost inscription (AE 1916, 0115) which was found at contrada Civitale, Bolsena in 1915, reads:

L(ucius) Caecina L(uci) (!) / q(uaestor) tr(ibunus) p(lebis) p(raetor) pr(o)co(n)s(ul)

IIIIvir i(ure) d(icundo) / sua pecu/nia vias / stravit

He was of senatorial rank, had served as quaestor and tribune at Rome and a praetor pro consule of an unnamed province. At Volsinii, as quattuorvir iure dicundo, he had paved a road at his own expense. According to Edward Bispham (referenced below, p. 492, entry Q59), the inscription on epigraphical grounds to the second half of the 1st century BC (but see further below).

The Caecinae were the most important family of Volaterrae (Volterra) but otherwise unknown at Volsinii. They had been particularly close to Cicero and adherents of the Republican cause at the time of Julius Caesar. Nevertheless, as Fiona Tweedie (referenced below, at p. 103) pointed out:

-

“... [while] the death of Cicero and victory of the triumvirs must have represented a set back for Volaterrae and the Caecinae, ... this is far from the end of the story. Caecinae continue to be prominent in both Volaterrae and Rome, well into the Julio-Claudian period.”

Cicero, in a letter to Atticus in November 44 BC, wrote that:

-

“[The young Octavian] sent a certain Caecina of Volaterrae to me, an intimate friend of his own, who brought me the news that [Mark Antony] was on his way towards the city with the legion ... He wanted my opinion [as to how he should respond]” (Letter to Atticus, 16:8)

Form Cicero’s tone, it seems that Octavian’s friend was not from the main branch of the family, with which he (Cicero) was well-acquainted. The same Caecina appears in an account by Appian:

-

“There was a certain Lucius Cocceius, a friend of both [Octavian and Mark Antony], who had been sent by Octavian, in company with Caecina, to [Mark Antony] i in Phoenicia [just before or during the Perusine War of 41-40 BC], and had remained with [Mark Antony] i after Caecina returned. ... When [Mark Antony] i allowed [Cocceius] to go, Cocceius asked, by way of testing his disposition, whether [Mark Antony] i would like to write any letter to Octavian making use of himself as his messenger. [Mark Antony] replied: ‘What can we write to each other, now that we are enemies, except mutual recrimination? I wrote letters in reply to his of some time ago, which I sent by the hand of Caecina. Take copies of those if you like’" (‘Civil Wars’, 5:60).

Fiona Tweedie (referenced below, at p. 103) suggested that:

-

“Octavian’s Caecina seems to have been a trusted agent, if his presence on this sensitive mission to [Mark Antony] is any indicator. He may be the key to understanding the conspicuous success of the gens Caecina under the Principate. If Cicero’s clients had found themselves stymied by their anti-Caesarian sentiments, another branch of the family may have found success by supporting the younger [Octavian]”.

Edward Bispham (referenced below, at p. 317 and note 176) asked:

-

“Might [Octavian’s Caecina be our L. Caecina? I think so.”

He suggested that L. Caecina’s Roman career had occurred after service at Naulochus, but that:

-

“... the shift towards more [the more overtly constitutional] exercise of power from 28 BC onwards may may have meant the eclipse of L. Caecina’s star, and semi-retirement to quiet municipal dignity. ... This reconstruction gives us a date in the later triumviral or early Augustan period for the quattuorvirate [at Volsinii]”

Lucius Seius Strabo and his Family

Lucius Seius Strabo

Strabo was born in Volsinii in ca. 46 BC and was of equestrian rank. He was first documented in a passage in which Tacitus described events immediately after the death of Augustus in 14 AD:

-

“The consuls, Sextus Pompeius and Sextus Appuleius, first took the oath of allegiance to Tiberius Caesar [Augustus’ successor]. It was [then] taken in their presence by Seius Strabo and Caius Turranius, chiefs respectively of the praetorian cohorts and the corn department” (‘Annals’, 1:7).

We do not know when Strabo secured this important post, which was introduced in 2 BC. Tacitus later recorded that:

-

“The commandant of the household troops, Aelius Sejanus, who held the office jointly with his father Strabo and exercised a remarkable influence over Tiberius, went [with the army to Pannonia in 15 AD] ... ” (‘Annals’, 1:24).

Cassius Dio recorded that:

-

“... Sejanus ... had shared for a time his father's command of the Pretorians; but, when his father had been sent to Egypt, ... he had obtained sole command over them ...” (‘Roman History’ 57:19).

Thus, Strabo ultimately became Prefect of Egypt, which was the pinnacle of an equestrian career. According to Robert Rogers (referenced below, at p. 369):

-

“Strabo appears to have died in [this] office ... [his tenure had extended from] ca. 15 to 16 or 17 AD.”

Despite his impressive career, Strabo is best remembered for his son, also Lucius Seius, who was later adopted into the Aelian family and thus known as Lucius Aelius Sejanus (see below), or simply Sejanus (mentioned above), who, as Praetorian Prefect, exercised substantial power under Tiberius until his (Sejanus’) assassination in 31 AD.

Strabo is almost certainly commemorated in two inscriptions from Volsinii. Both of these inscriptions have been mutilated, and neither preserves the name of the man commemorated: we might reasonably assume that this mutilation had happened in 31 AD, after the assassination of Sejanus. The surviving fragments read:

-

✴CIL XI 2707 (1 - 15 AD), from an unknown location and now lost, read:

[L(ucio) Seio ...]

[Str]aboni

[pra]efecto

[pra]etori

-

✴CIL XI 7285 (ca. 15 AD), from Poggio Moscini, now in the Museo Archeologico, Florence, reads:

[.....]

praefectus Aegypt[i et]

Terentia A(uli) f(ilia) mater eiu[s et]

Cosconia Lentulii(!) Malug[inensis f(ilia)]

Gallitta uxor eius ae[dificiis]

emptis et ad solum de[iectis]

balneum cum omn[i ornatu]

[Volsiniens]ibus ded[erunt]

[ob publ]ica co[mmoda]

-

Since the man commemorated had built a “balneum” (bathing chamber) for public use, the inscription presumably came from the thermal complex here.

Some scholars have doubted that the second of these inscription did, in fact, commemorate Strabo (see for example, Pierre Gros, referenced below, 2013, at p. 95), but this view seems to be losing ground. For example, Francis Cairns (referenced below, at p. 21, note 109) observed that:

-

“[Ronald] Syme [referenced below, 1986, at pp. 301-4] convincingly recovers CIL XI 7285 for L. Seius Strabo.”

If this is correct, this second inscription provides the following informatiom:

-

✴Strabo’s wife (perhaps his second wife) was Cosconia Gallitta, the daughter of Cornelius Lentulus Maluginensis, the suffect consul of 10 AD.

-

✴More importantly for our present purposes, Strabo’s mother, Terentia, was the daughter of “Aulus”:

-

•this was probably Aulus Terentius Varro Murena, whom Augustus executed for treason in 24 BC (see, for example, Ronald Syme, referenced below, 1986, at p. 301);

-

•in which case, Strabo’s mother was the niece of another Terentia, the wife of Maecenas and sister of the executed Murena: according the Cassius Dio (above), who might have been recycling inaccurate gossip, Terentia, the wife of Maecenas, was also the lover of Augustus, with whom she travelled to Gaul in 16 BC.

Lucius Aelius Sejanus

As we have seen, the notorious Sejanus succeeded his father as Pretorian Prefect under Tiberius and, in this capacity, became the most important (and probably the most feared and hated) man in Rome until his execution in 31 AD.

Despite the family’s success in Rome until this point, its continuing association with Volsinii and with the cult of Nortia is clear from a poem by Juvenal, in which he muses on the behaviour of the mob following Sejanus’ execution:

-

“But what of the Roman mob?

-

They follow Fortune, as always, and hate whomever she condemns.

-

If Nortia, as the Etruscans called [Fortuna], had favoured Etruscan Sejanus;

-

If the old Emperor [Tiberius] had been surreptitiously smothered [to clear the way for him];

-

That same crowd ... would have hailed [Sejanus as] their new Augustus” (‘The Vanity of Human Wishes’ - search this link on ‘Nortia’).

Aulus and Lucius Seius, the sons of Aulus

A now-lost inscription (AE 1983, 0395) from Poggio Moscini, which was published by Mireille Corbier, referenced below), commemorated two other members of family of L. Seius Strabo (above):

A(ulus) L(ucius) Seii A(uli) f(ilii) curatores aquae

ex aere conlato

Fonti Telluri sacr(um)

Mireille Corbier identified these as the brothers Aulus and Lucius Seius, the sons of Aulus Seius senior, and suggested (at p. 726) that the inscription:

-

“...could hardly be later than the Augustian period, albeit that there is a margin of uncertainty”

This suggests that the brothers were nephews of L. Seius Strabo. Pierre Gros (2013, referenced below) suggested that each held the post of Curator Aquarum (a post related to the administration of the aqueduct) and that they had probably financed a fountain fed by the aqueduct in question that was dedicated to the divinities Fons and Tellus.

Maecenas (again)

As noted above, Maecenas had enjoyed a high level of delegated authority during Augustus’ absence for peninsular Italy in 38-6 BC. He probably continued to do so for a period thereafter, although the sources are scant. However, according to Kenneth Reckford (referenced below, at pp. 196-7) :

“Octavian’s return [to Rome after Actium] and his triple triumph in the summer of 29 BC put an end to the special powers of the man who has been called his First Minister. There is not a single fact to support the idea that Maecenas’ political career continued after 29 BC”

He concluded (at p. 198):

-

“The [few] facts that we do possess point to one simple and unromantic conclusion: Maecenas went into voluntary semi-retirement after 29 BC. [The most important reason was that], as early as 29 or 28 BC, Maecenas was a very sick man.”

He pointed out (at p. 199) that:

-

“... there is no solid evidence to support the view that Augustus’ friendship with Maecenas cooled after 23 BC [,the time of the execution of Maecenas’ brother-in-law,] ... indolence and sickness account adequately for the missing years, from semi-retirement in 29 BC to death in 8 BC.”

Thus we can probably discount Cassius Dio of the reasons why Augustus did not delegate the administration of Italy to Maecenas when, in the summer of 16 BC, he:

-

“... set out for Gaul ..., making the wars that had arisen in that region his excuse. For, since he had become [unpopular in Rome] ..., he decided to leave the country, somewhat after the manner of Solon. Some even suspected that he had gone away on account of Terentia, the wife of Maecenas, and intended ... to live with her abroad free from all gossip. ... [He] committed the management of [Rome] and the rest of Italy to [Titus Statilius Taurus], since he had sent Agrippa again to Syria, and since he no longer looked with equal favour upon Maecenas, because of the latter's wife ...” (‘Roman History’, 54:19:3).

We need not believe all of this gossip about Augustus and Terentia, but it is certainly true that, for whatever reason, Maecenas was no longer involved in public affairs in the way that he had been at the time of the Etruscan revolt (above).

Semi-retirement and ill health need not have precluded Maecenas’ influence with Augustus, particularly in matters relating to the projection of Augustus’ image in Etruria. We might include among his his possible agent in this putative endeavour: Lucius Caecina (who might similarly have been semi-retired since ca. 28 BC) and Lucius Seius Strabo (whose mother had probably been the niece of Maecenas’ wife).

Theatre (1st century BC)

Aerial view, with modern Bolsena (at the lower left )

The original forum of Volsinii was at Meractello, the later the site of the Flavian amphitheatre

The site of the ‘Flavian’ forum is now the Archeological Area at Poggio Moscini

An inscription (CIL XI 2710) that was found in 1536 in località Mercatello (the site of the original forum and subsequently the site of the amphitheatre), which is now in the Museo Territoriale del Lago di Bolsena ,records a now-lost theatre:

L(ucius) Cominius L(uci) f(ilius) A(uli) n(epos)

C(aius)/ Canuleius L(uci) f(ilius)

T(itus) Tullius T(iti) f(ilius)/ Kanus

L(ucius) Hirrius L. f. Latinus

IIIII vir(i)

theatrum et proscaenium

de sua/ pecunia faciundum coeraverunt

More specifically, this inscription records the names of the quattuorviri who had financed the construction of a “theatre and proscenium”. Jean-Paul Thuillier (referenced below, at p. 599) dated it “without doubt” to the late 1st century BC. The inscribed stone was subsequently split into two parts, only one of which survives, but the whole inscription is known from a transcription of 1544.

Luigi Sensi (referenced below) referred to a now-lost, double-sided inscription (AE 1985, 0384) from Poggio Moscini (the site of the later forum, now the archeological area of Bolsena, to the left in the aerial view above) that he thought probably related to this theatre:

Post pulpitum/ mulierum locus/ cubantum

latum pedes/ XIII //

longum/ pedes/ VIII

This described the dimensions of a space in front of a pulpit, in which women (presumably only women) could lie down. He suggested that the women who made use of this pulpit and the space in front of it were probably hoping for a divine apparition, perhaps of the goddess Nortia, during the night.

Scholars (all referenced below) differ as to the location and status of this theatre:

-

✴Pietro Tamburini suggested that the remains of a structure that were found in 2001 during the excavation of a site at Pianforte, outside the walls of Volsinii, probably date to the late 1st century BC and probably relate to the theatre recorded in the inscription(s) above. However Pierre Gros (referenced below, 2013, at p. 91 and pp. 103-4) argued that these remains more probably related to a jetty.

-

✴Pierre Gros (1981 and 2013) pointed out that Livy [40:51:3] used the phrase "theatrum et proscaenium ad Apollinis" when describing what was apparently a temporary theatre that was regularly set up near the Temple of Apollo in Rome before the construction of the Theatre of Marcello there. He suggested that the "theatrum et proscaenium" that had been financed by the quattuorviri at Volsinii had also been a temporary arrangement. While a permanent structure was almost certainly built at a later date, its location was unknown.

-

✴Luigi Sensi suggested that the theatre was possibly still in construction at the time of the inscription. If it had been in what is now località Mercatello, it might well have been demolished in the Flavian period to make way for the amphitheatre and rebuilt in an unknown location.

Cult of Nortia

I suggested in my page on Campo della Fiera in the Republican Period that the ancient federal sanctuary at Campo della Fiera, below Orvieto, had lost its federal status in 264 BC, and that it subsequently became an extra-urban sanctuary of Roman Volsinii, dedicated to Nortia. The people of Volsinii consequently retained the cult of this Etruscan goddess for centuries

Two inscriptions, which are difficult to date, but which could belong to the early Empire, record ex-votos to the goddess Nortia, presumably from a cult site of the goddess inside the city:

-

✴CIL XI 2685, which from an unknown location and which is now in the Museo Territoriale del Lago di Bolsena, commemorates an offering made by Caius Larcius Agathopus (who, judging from his name, was probably a freedman):

-

D(eae) N(ortiae) M(agnae) S(anctae)

-

C(aius) Larcius / Agathopus vot(um) sol(vit)

-

✴CIL XI 2686, which came from a site near San Francesco (in the centre of Bolsena) and which is now lost, commemorated an offering made by Primitivus, a public/ municipal slave:

-

Dis deabusq(ue)

-

Primitivus

-

Deae Nort(iae)

-

ser(vus) act(or)

-

Primitivus was probably the rei publicae servus actor mentioned in CIL XI 2714 (a now-lost inscription that was once embedded in the wall of a house near Santa Cristina), who dedicated the epitaph of his wife, Rufia Primitiva,

Other Inscriptions

Gaius Caesar (1 AD)

A fragmentary and now-lost inscription (AE 1981, 0350) that was found in 1979 during excavations of the thermal complex at Poggio Moscini (now the archeological area of Bolsena) read:

[C(aio) Caesari] A[ugusti]/ [filio]

prin[c]ipi /[iuve]ntutis

pont[if(ici)]/ [c]o(n)s(uli)

The title “princeps iuventutis” (the first amongst the young), which was often bestowed on potential successors to the emperor, was first given to Gaius and Lucius, the adopted sons of Augustus. This inscription probably commemorated the former, who served as consul in 1 AD.

? Volsinius Victorinus

An inscription (CIL XI 2710a) that has been embedded in the campanile of Santa Cristina commemorates:

... Volsinio/ [V]ictorino

q(uin)q(uennali) coll(egii) fabr(um)

Augustal[i]

tabul(ario) rei publ(icae)

[V]olsiniens(ium) / [i]t(em) Ferenti/ensium

Volsinius Victorinus who was a freed slave of the municipium, had served as:

-

✴Augustales (member of a municipal magistracy open to freedmen);

-

✴tabularius rei publicae (public archivist) of Volsinii and nearby Ferentium; and

-

✴quinquennalis of the Collegium Fabrum (blacksmiths’ guild).

According to Franco Luciani (referenced below, paragraph 8):

“... there are many testimonies of [freed municipal slaves] who, even after manumission, continued in their work for the municipium. It is not surprising that most of them refer to those who had been employed as tabularii: the tasks of the municipal archivist required expertise, reliability and a good level of literacy. It is unsurprising, therefore, that the city authorities were inclined to maintain experienced persons in such roles ... Emblematic is the case of ? Volsinius Victorinus ..., who was tabularius publicus, not only in his affiliated city [of Volsinii]. but also in the nearby Ferentium.

Read more:

F. Luciani, “Cittadini come Domini, Cittadini come Patroni: Rapporti tra Serui Publici e Città Prima e Dopo la Manomissione”, in

M. Dondin-Payre and N. Tran (Eds), “Esclaves et Maîtres dans le Monde Romain”, (2016) Rome

F. Tweedie, “Volaterrae and the Gens Caecina”, in

S. T. Roselaar (Ed.), “Processes of Cultural Change and Integration in the Roman World”, (2015) Leiden and Boston, pp. 92-105

A. Ambrogi and I. Caruso, “Arte di Età Imperiale: i Ritratti di Costantino e di Domizia Longina”, in:

G. della Fina and E. Pellegrini (Eds), “Da Orvieto a Bolsena: un Percorso tra Etruschi e Romani”, (2013 ) Pisa, pp 326-8

P. Gros, “La Nuova Volsinii: Cenno Storico sulla Città”, in

G. della Fina and E. Pellegrini (Eds), “Da Orvieto a Bolsena: un Percorso tra Etruschi e Romani”, (2013 ) Pisa, (pp 88-105)

A. Ambrogi, “Ritratto di Augusto-Costantino”, in

A. Bravi (Ed.), “Aurea Umbria: Una Regione dell’ Impero nell’ Era di Costantino”, Bollettino per i Beni Culturali dell’ Umbria, (2012) pp 128-30

E. Bispham, “From Asculum to Actium: The Municipalisation of Italy from the Social War to Augustus”, (2008) Oxford

F. Cairns, “Sextus Propertius: The Augustan Elegist”, (2006) Cambridge

J. Osgood, “Caesar’s Legacy”, (2006) Cambridge

S. P. Oakley, “A Commentary on Livy, Books VI-X: Volume IV, Book X”, (2005 ) Oxford

I. Gradel, “Emperor Worship and Roman Religion”, (2002) Oxford

P. Tamburini, “Bolsena: Emergenze Archeologiche a Valle della Città Romana”, in

G. della Fina (Ed.), “Perugia Etrusca”, Annali della Fondazione per il Museo ‘Claudio Faina’, 9 (2002) pp 541-80

L. Sensi, “In Margine al Rescritto Costantiniano di Hispellum” in

“Volsinii e il suo Territorio”, Annali della Fondazione per il Museo ‘Claudio Faina’,

6 (1999) 365-71

J. Hall, “From Tarquins to Caesars: Etruscan Governance at Rome , in:

J. Hall (Ed.), “Etruscan Italy: Etruscan Influences on the Civilizations of Italy from Antiquity to the Modern Era”, (1996) Provo, Utah, pp. 149-90

D. Boschung, “Die Bildnisse des Augustus”, (1993) Berlin

F. Tassaux, “Pour une Histoire Économique et Sociale de Bolsena et de son

Territoire”, Mélanges de l'Ecole Française de Rome: Antiquité , 99:2 (1987) 535-61

E. Gabba, “Trasformazioni Politiche e Socio-Economiche dell' Umbria dopo il Bellum Perusinum” in

G. Catanzaro and F. Santucci (Eds.), “Bimillenario della Morte di Properzio: Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi Properziani”, (1986) Assisi, pp 95-104

A. J. M. Watson, “Maecenas’ Administration of Rome and Italy”, Akroterion, 39 (1994) 98-104

J. Thuillier, “Les Édifices de Spectacle de Bolsena: Ludi et Munera”, Mélanges de l'Ecole Française de Rome, Antiquité, 99:2 ( 1987) 595-608

R. Syme, “The Augustan Aristocracy”, (1986) Oxford

M. Corbier, “La Famille de Séjan à Volsinii : la Dédicace des Seii, Curatores Aquae”, Mélanges de l'Ecole Française de Rome: Antiquité, 95:2 (1983) 719-56

P. Gros, “Bolsena I: Scavi della Scuola Francese di Roma a Bolsena

(Poggio Moscini): Guida agli Scavi”, Mélanges d' Archéologie et d' Histoire, 6 (1981)

W. Harris, “Rome in Etruria and Umbria”, (1971) Oxford

S. Weinstock, “Divus Julius”, (1971) Oxford

K. J. Reckford, “Horace and Maecenas”, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 90 (1959) 195-208

R. S. Rogers, “The Prefects of Egypt under Tiberius”, Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, 72 (1941), 365-71

R. Syme, “Roman Revolution”, (1939) Oxford

Ancient History: Velzna/ Volsinii Destruction of Velzna

Volsinii (Bolsena): Republican Period; TriumviralPeriod;

Early Empire; Imperial Period; Late Empire;

Rescript of Constantine at Hispellum (ca. 335 AD)

Return to the page on History of Orvieto.