Depopulation of Roman Fulginia (5th century ?)

As discussed in my page on the Location of Roman Fulginia, it seems that the Roman city (whether it was on the site of the modern city or in the area around Santa Maria in Campis) was effectively abandoned in late antiquity. Given its strategic location and its apparent lack of city walls, it is possible that this process of depopulation began during the period of insecurity that extended from the sack of Rome in 410 until the fall of the last Roman emperor in the west in 476. However, if so, the process might well have been arrested during the stability ushered in under Goths.

Gothic Kingdom (476 - 535)

Odoacer (476 - 493)

In the decades after 476, when the Goth Odoacer seized power in the west, the security situation in Italy improved very considerably. Foligno seems to have been part of an active Christian society in Umbria at this time. Pope Felix III, the first pope to be elected in the new political environment, seems to have had good relations with Odoacer, and Foligno sent one of the six Umbrian bishops to the synod that he held in Rome in 487. The six (who are in the list of attending bishops published by Giovanni Domenico Mansi, referenced below, Volume 7, p. 1171) were:

-

✴Martianus of Amelia;

-

✴Innocentius of Bevagna;

-

✴Urbanus of Foligno;

-

✴Herculeus of Otricoli;

-

✴Epiphanius of Spello; and

-

✴Cresconius of Todi.

Spoleto was probably the most important of the nearby diocese, and we might reasonably assume that Bishop Amasius of Spoleto was absent only because of ill health: his epitaph records his death, at the age of 85, in 489.

As noted on my page on Early Christianity in Foligno, Bishop Urbanus, was the first securely documented bishop of Foligno:

-

✴He was designated as ‘Urbano Fulginati’ when he attended the Roman synod of 487 mentioned above.

-

✴He was recently-deceased in 496, when Pope Gelasius I wrote to three bishops of other dioceses (John of Spoleto; Cresconius of Todi; and a third bishop) directing them to investigate a legal claim against him. In this letter, which was published by Samuel Lowenfeld (referenced below, at p. 10 - search on ‘Cresconio’), Urbanus was described as “religiose recordationis Fulginatis civitatis antistitem”, the devoutly remembered bishop (or overseer) of civitas Fulginia.

I speculated in the earlier page that the civitas Fulginia of 496 could have been on Colle San Lorenzo, with the episcopal seat still at San Valentino (later San Valentino di Civitavecchia). There are, however, at least two other possibilities:

-

✴it could have been on the site of medieval Foligno, which was designated as ‘civitas Fulginia’ from ca. 850; or

-

✴it could have been in the area of Santa Maria in Campis, if (as some scholars believe) Roman Fulginia was located here and abandoned only in late antiquity.

It has to be said, however, that there is no evidence of Christian cult site in either location at this early date.

Theodoric (493-526)

Theodoric, another Goth, seized power from Odoacer in 493, with the support of (and perhaps at the instigation of) the Emperor Zeno. His reign was noted for good government and for works of restoration of the ravaged cities of Italy. Theodoric established Spoleto as the administrative heart of central Italy, and this probably marks the start of Spoleto's period of dominance over the region. He repaired the fortifications of the city, as well as those of Orvieto, Perugia and Todi. He also kept garrisons at Assisi, Narni and Norcia.

Sixteen bishops from Umbria attended at least one the synods of 499, 501 and 502 that Pope Symmachus convened in Rome during the papal schism. (They can be found in the lists of attending bishops published by Giovanni Domenico Mansi, referenced below, Volume 8: pp. 234-8 for 499; pp. 251-3 for 501; and pp. 268-9 for 502). They included:

-

✴Bishop Fortunatus of Foligno, who was probably the successor of Bishop Urbanus, and who attended all three synods (designated as ‘Fortunatus Epicopus Ecclesias Fulgintinae’ in 499 and as ‘Fortunatus Fulginas’ in 501 and 502); and

-

✴Bishop Boniface of Forum Flaminii (Bonifacius Foroflaminiensis), who also attended the synod of 502.

It seems likely that, during this period, the episcopal seat of Fortunatus remained at “civitas Fulginia’, wherever that was. It is entirely possible that Boniface had his seat at the paleochristian basilica that has been excavated at Forum Flaminii (described below).

Gothic Wars (535 - 552)

If Roman Fulginia (on or near Via Flaminia) was still inhabited in the 6th century, it must surely have been affected by these wars, which led to the Byzantine reconquest of Italy. In particular, Umbria was an important theatre of war after the the Byzantine general, Belisarius, returned to Italy in 544 to confront the new Gothic general Totila. According to Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 62):

-

“Although [the Byzantine historian] Procopius does not mention it, Foligno must have suffered from the transit and presence of the Goths, even though, being a city without walls, it had no strategic value. Certainly, it must have been affected by the passage of the Goths in 545, when Totila, having conquered Fermo and Ascoli, moved against Spoletium and then laid siege to Asisium. The route taken by the Goths, once they had joined the eastern branch of Via Flaminia [from Ascoli], seems, on all the evidence, to have been the transversal route recorded in the [‘Geografica’ of Guidone] that ran from Foligno to Cortona, passing Assisi and Perugia” (my translation).

Totila presumably marched back along the eastern branch of Via Flaminia, which was now protected by his garrison at Spoletium, in order to mount his successful attack on Rome in 546. The impact on Fulginia is difficult to estimate:

-

✴Given its lack of walls, Foligno would not have housed a Byzantine garrison, and there is no reason to think that Totila would have regarded its inhabitants as hostile.

-

✴On the other hand, the demands of marching armies, however well-intentioned, could have created an air of insecurity and encouraged further depopulation.

Totila was able to consolidate his position in 548, when Belisarius was recalled to Byzantium. The Emperor Justinian sent the aged Narses to redeem the situation in 552. Narses landed near modern Venice and marched down the coast to Ravenna, where he met no resistance. Totila mustered his forces at Rome, and the respective armies marched along Via Flaminia to engage at Taginae (near modern Gualdo Tadino). Narses emerged victorious, and the wounded Totila died as he fled the field. Although hostilities continued for a while, the Gothic cause in Italy was lost.

After this victory, Narses continued along Via Flaminia, towards Rome. Procopius reported that he:

-

“... took Narnia by surrender and left a garrison at Spoletium, which was then without walls, ordering [his soldiers] to rebuild as quickly as possible those parts of the fortifications that the Goths had torn down. And he also sent some men to make trial of the garrison in Perusia” (‘History of the Wars’, VIII xxxiii 9).

At this time, Perusia was in the hands of the renegade Roman soldier soldier Uliphus. His fellow-deserter and deputy, Meligedius, changed sides once more: he had Uliphus murdered and surrendered Perusia to Narses. Narses then took Rome and sent the keys of the battered city to Justinian. Again, Procopius makes no mention of Foligno in this detailed account, and it might well have been essentially uninhabited.

There are no surviving records of bishops of either Forum Flaminii or Fulginia for almost 180 years after the synod of 502. However, there is nothing to suggest that either the basilica at Forum Flaminii or the old episcopal church on Colle San Lorenzo fell into disuse. It is also possible that the population or repopulation of what became medieval Foligno began soon after the Byzantine conquest, albeit that the only evidence for this is in the dedication of the church of Sant’ Apollinare.

Sant’ Apollinare

-

“The diffusion in Italy of the cult of Sant’ Apollinare occurred ... in the 6th century, with the ‘Byzantine’ domination, to the point of becoming emblematic of Byzantine presence and hegemony in the west. In Umbria, it was widely diffused, thanks in part to the channels of communication between Rome and Ravenna represented by Via Amerina and Via Flaminia. This supports the hypothesis [developed in their book] of the presence here of a strategically placed fortress that housed this cult site dedicated to St Apollinaris of Ravenna, which had been founded following the Byzantine reconquest [in 554] and which resulted in the urban settlement of the area around the fortress itself” (my translation).

They expanded on the function of this putative fortress (at p. 162):

-

“A strategically placed fortress commanding the local lines of communication [including the Topino and both branches of Via Flaminia] and providing a potential refuge for the local population in case of danger could have served as the nucleus for the formation of medieval Foligno, which, together with the presence of the martyrium of St Felician, would have attracted people from the nearby Roman Fulginia and, in time, supplanted it” (my translation).

As noted above, the belief that Roman Fulginia was near to, rather than coincident with, the modern city, while widely held and underlying the hypothesis above, is not universally accepted. It is alternatively possible that the Roman city had been coincident with the modern city, but that it had been depopulated in the 5th or early 6th century. In this case, the putative Byzantine fortress might well have made use of the remains of part of Roman Fulginia and nucleated the resettlement of the area.

Lombard Period (568 - 774)

After the Lombard invasion of 568, much of Byzantine Italy fell into their hands.

-

✴The Lombard kingdom was established in northern Italy, with Pavia as its capital.

-

✴Foligno, Forum Flaminii and the surrounding localities formed part of the Lombard Duchy of Spoleto, which Duke Faroald I created in ca. 575 .

The Duchy of Spoleto was separated from the Lombard kingdom by the so-called Byzantine corridor from Rome to Ravenna.

Despite their political and geographic separation, the dioceses of Lombard Italy continued to communicate with Rome. Thus, nine bishops from modern Umbria attended the council that Pope Agatho at Easter 680, which issued the decree condemning Monotheletism, some from within the Duchy of Spoleto and others in what was still Byzantine-held territory. (The full list can be found in the lists of attending bishops published by Giovanni Domenico Mansi, referenced below, Volume 11, p. 303). They included

-

✴Florus of Foligno (Fulginatis Ecclesiae); and

-

✴Decentius of Forum Flaminii (Foroflaminienius Ecclesiae).

According to Mario Sensi (referenced below, 199o, at pp. 328-30) Florus was the first securely-documented bishop of Fulginia since 502:

-

✴Some scholars (including Feliciano Marini, referenced below, at p. 13, entry 13) record a Bishop Candidus who attended a synod held in Rome by Pope Gregory I in 595. However, the diocese of this bishop was given as “civitas Bulsinensis”, and he was more probably Candidus of Bolsena/Orvieto, who was also documented in 591 and 596.

-

✴Mario’ Sensi’s list of bishops of Foligno also included a Bishop Candidus (documented in 695), although I have not managed to find any other information about him. I think this might have been a slip for the Candidus listed by other scholars under 595, discussed above, who was more probably a bishop of Bolsena/Orvieto.

According to Feliciano Marini (referenced below, at p. 14), who cited Ludovico Jacobilli, Bishop Eusebius (740-60) was:

-

“... consecrated by Pope Gregory III. Through his penitence and prayer, he saved Foligno from sack and destruction at the hands of the Lombard King Liutprand in 740, after he had destroyed the nearby cities of Forum Flaminii, Plestia, Tadino and Massa Martana. He then gave refuge to the people of Forum Flaminii, whose diocese, together with part of the diocese of Plestia, was absorbed by that of Foligno” (my translation).

However, Mario Sensi (referenced below, 1990, at pp. 328-30) doubted the existence of Bishop Eusebius. As far as I know, these depredations of Liutprand are otherwise undocumented.

A document (763) in the ‘Regestum Farfense’ (1092-1100) complied by Gregorio di Catino (search on ‘fulginea’) provide a rare record of Foligno at this time: this document, in which Audisio of Rieti offered his son Auneperto to the abbey and made a donation of possessions that belonged to both of them, was witnessed by ‘Hauto sculdhais de fulginea’. This reveals that Fulginia was administered by a ‘Scultheis’. According to Katherine Fischer Drew (referenced below, at p. 240, note 10), in Lombard law in the 8th century:

-

“A ‘Scultheis’ was a royal representative lower in rank than a gastald and responsible to him. This official also had administrative and judicial duties, but in all his work he was subject to the immediate supervision of his gastald. He presided over a subdivision of the civitas sometimes called a ‘sculdascia’”.

Mario Sensi (referenced below, 1994, at p. 90) speculated that he might have been based near the church of San Valentino on Colle San Lorenzo (see below).

Fulginia was documented in this register again in 791, when Duke Winichis of Spoleto (789-822) ruled against Goderisio of Rieti, who, having fallen on hard times, had tried to recover property in “Spoleto, Interamnes seu Fulginea” (Spoleto, Terni and Foligno) that he had previously donated to the abbey.

San Valentino

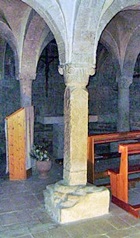

As discussed the page on early Christianity in Foligno, the bishops of Foligno probably had their episcopal church at San Valentino, on Colle San Lorenzo from ca. 400. The following finds from this church suggest that it remained in use, quite possibly as the episcopal church, into the Lombard period. If this is correct, then this would have been the episcopal seat of Bishop Florus.

San Valentino was documented as a parish church (“plebem sancti Valentini”) in 1138, when Pope Innocent II confirmed it as a possession of the Bishop Benedetto of Foligno.)

Lid of a Sarcophagus (8th century ?)

Four fragments of the lid of a sarcophagus were moved from San Valentino to the crypt of the Duomo in 1918. Unfortunately, the last part of the inscription is missing, so we do not know the identity of the deceased. What survives of the inscription reads:

Hic requ[ies]cet in pace [...]

The form of words indicates that the deceased was a Christian and, given the find spot, we might reasonably assume that he had been buried in the cemetery of San Valentino. Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1985, at pp. 316-7) dated the inscription to some time around the 8th century.

Cross (8th century)

-

“... was found by Faloci Pulignani in a burial site, and is known only from his sketch, since it has since been lost. We are dealing with a small cross, some 5 cm across, cut out of gold foil ... In recent studies, it is considered the unique case of a cross adorned with pressed decoration from the Lombard period that is known in the Duchy of Spoleto” (my translation).

Forum Flaminii

As noted above, Forum Flaminii had its own bishop, at least from 502. However, the only securely-documented documented early bishops of Forum Flaminii are:

-

✴Bishop Boniface, who attended the synod in Rome of 502, alongside Bishop Fortunatus of Fulginia; and

-

✴Bishop Decentius, who attended the synod in Rome of 680, alongside Bishop Florus of Fulginia.

Christian Basilica (6th century ?)

An early basilica was discovered 1929, on a site that was apparently some 100 meters from the church of San Giovanni Profiamma (the ancient site of Forum Flaminii). Unfortunately, the exact location of the discovery is now unknown. The basilica was only partially excavated, but a sketch made at that time recorded an apse, adjacent to the start of a nave and two side aisles. According to Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1981, at p. 9), it could be inferred from this sketch that the original structure was:

-

“... a large basilica made up of a tripartite longitudinal hall and a distinct apsed area” (my translation).

-

✴a peacock on one side;

-

✴a cross in a circle (above a geometrical pattern) on the second; and

-

✴a cross in a circle above a grape vine on the third.

According to Josselita Serra Raspi (referenced below, at 369-70 and Figures 3 and 5), the surviving fragment was perhaps half of an architrave that had been used in a presbytery, in which the undecorated side would have faced upwards in a location in which it would not have been visible. The motifs on the surviving half of the architrave would have been reflected symmetrically on the other half. She dated the architrave to the middle of the 8th century. Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1981, at p. 17) suggested that it might have been carved originally for this earlier basilica.

Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1981, at p. 17) also suggested that this early basilica might have been the source for the statement in the Legend of St Felician that he had been arrested while praying ‘in basilica quae appellatur palatina’ (in the palatine basilica). If so, it might well have been dedicated to St Felician by the 9th century, when the author of the legend (guided by the bishop of Civitas Fulginia who probably commissioned it) acknowledged that St Felician had been bishop of Forum Flaminii. It might well have been the episcopal church of both Bishop Boniface (documented in 502) and of Bishop Decentius (documented in 680).

Medieval Foligno

San Salvatore

-

✴It was first documented as the “monasterio quoque sancti Salvatoris”in 1138, when Pope Innocent II confirmed it as a possession of the Bishop Benedetto of Foligno.

-

✴Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 93 and note 373) described a document in the archives of the Abbazia di Sassovivo dated 1217 in which San Salvatore was ‘extra murum civitatis’: it is likely that it was just outside the Porta Antica della Badia.

However, Ludovico Jacobilli (referenced below, at p. 147) believed that the monastery had been established by St Vincent, whom he identified as one of the 300 Syrian monks who came to Italy in the 6th century. Despite the frailty of his hagiographic sources, there might well have been a factual basis for the account: according to Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 139):

-

“... the dedication of this church as San Salvatore, its monastic character and its suburban location [it was ‘extra murum civitatis’ in 1217] all suggest ancient origins. ... [The examples of] the churches dedicated as San Salvatore in Spoleto, Terni, Narni, Calvi and Otricoli suggest a link to the Lombard presence in the territory” (my translation).

They proposed (at p. 301, entry 78) a date in the late 6th century.

Area of Santa Maria in Campis

Sarcophagus (ca. 600 ?)

Luigi Sensi (referenced below, 1982) described a sarcophagus that was discovered in the late 19th century in an unknown location in the area around the church of Santa Maria in Campis. The sarcophagus, which was taken to the museum of Foligno after its discovery, was destroyed in the Second World War. However, a photograph of it survives (reproduced by Luigi Sensi as Figure 1). He pointed out that it shared the characteristics of other Umbrian sarcophagi, two of which had housed the relics of saints (those of St Juvenal, in the Duomo of Narni; and those of St Felix, in the crypt of San Felice di Giano). The sarcophagi in this group are characterised by a low relief on one side that consists of a rectangle flanked by two triangles and then by two arches with architraves. A wide variety of dates has been proposed for this group of sarcophagi: that suggested here was suggested by Mario Sensi (referenced below, 1994, at p. 90):

-

“The sarcophagus at Foligno which was contemporary with those from Giano, Narni and Spoleto, is assignable on the basis of [the shared] decorative motif to the 6th or 7th century” (my translation).

Luigi Sensi acknowledged that the find spot recorded for the sarcophagus from Foligno was unspecific, but he suggested that it might have come from the cemetery of an early church at Santa Maria in Campis, which he described (as pp. 30-1) as:

-

“... an ancient basilica [with an associated cemetery], which retained the memory of the first Christian community of Fulginia ...” (my translation).

He suggested that the sarcophagus had been used for the relics of SS Carpophorus and Abundius after their discovery in this cemetery. It has to be said that this suggestion was based on purely circumstantial evidence, and there is no surviving evidence for either this early church in the area of Santa Maria in Campis or for its putative Christian cemetery.

Read more:

E. Calandra, “Mosaico: Forum Flaminii”, in”

A. Bravi (Ed.), “Aurea Umbria: Una Regione dell’ Impero nell’ Era di Costantino”, Bollettino per i Beni Culturali dell’ Umbria, (2012) p. 84

P. Guerrini and F. Latini, “Foligno: Dal Municipium Romano alla Civitas Medievale: Archeologia e Storia di una Città Umbra”, (2012) Spoleto

M. Sensi, “Le Cattedrali di Foligno”, in

G. Benazzi (Ed.), “Foligno A.d. 1201: La Facciata della Cattedrale di San Feliciano”, (1994) Foligno, pp 88-111

M. Sensi, “Visite Pastorali della Diocesi di Foligno: Repertorio Ragionato”, (1991) Foligno

The list of bishops (at pp. 328-30) mentioned above is available on-line in the website of the Centro Studi Federico Frezzi.

M. Brozzi, “Una Croce Aurea Longobarda Scoperta nel Territorio di Foligno”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 14 (1990) 482-6

L. Sensi, “La Raccolta Archeologica della Cattedrale di Foligno”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 9 (1985) 305-26

L. Sensi, “Un Sarcofago Paleocristiano da Santa María in Campis”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 6 (1982) 19-34

L. Sensi, “La Basilica Paleochristiana di Forum Flaminii”, Bollettino Storico della Città di Foligno, 5 (1981) 9-22

J. Serra Raspi, “La Scultura dell' Umbria Centro-Meridionale dall' VIII al X Secolo”, in:

“Aspetti dell' Umbria dall' Inizio del Secolo VIII alla Fine del Secolo XI: Atti del III Convegno di Studi Umbri, Gubbio, 23 - 27 Maggio, 1965”, (1966) Perugia, pp. 365-86

K. Fischer Drew, “The Lombard Laws”, (1973) Pennsylvania F. Marini, “I Vescovi di Foligno: Cenni Biografici”, (1948) Treviso

S. Lowenfeld, “Epistolae Roma-norum Pontificum Ineditae”, (1885) Leipzig

G. Mansi, “Sacrorum Conciliorum Nova et Amplissima Collectio Origina”, (1758-98) Venice and Florence

L. Jacobilli, “Vite de' Santi e Beati di Foligno”, (1628)

Return to History of Foligno