12th century

It is likely that the Bishop of Foligno effectively ruled the new city, advised by the prominent men in the community. Thus, an inscription that records the rebuilding of the Duomo in 1133 gives pride of place to the bishop, Marco, but also mentions the “magnus Lothomus” and the “comarchus Acto”. Lothomus was almost certainly a feudal magnate, and Acto (Atto in Italian) may have been another influential layman.

The speed with the new city grew is evident in the privilege that it received in 1138 from Pope Innocent II, by which time the diocese included large areas towards Bevagna, Spello, Trevi and Nocera Umbra. The document defined the boundaries between the diocese and the powerful monastery of Santa Croce di Sassovivo, which then controlled some 34 churches over a wide area that included outposts in Perugia and Rome.

When the Emperor Frederick I passed through Umbria in 1155 after his coronation, only Foligno and Todi enjoyed his favour. Anselmo degli Atti became Bishop of Foligno in 1160, a post he was to hold until his death in 1201. The diocese of Foligno absorbed that of Nocera Umbra in ca. 1160 because of the unrest caused by the papal schism. Anselmo, who now had responsibility for both dioceses, seems to have spent the period 1161-7 in the monastery of San Pietro di Landolina outside Foligno, presumably because of the difficult situation in both cities.

Foligno had a communal government by the time of the Treaty of Venice (1177) between Pope Alexander III and Emperor Frederick I. In a document (1177) referring to the “consulibus fulginatibus dilectis fidelibus” (beloved and faithful consuls of Foligno), Frederick I recognised the boundaries of Foligno that had been defined in 1138 and transferred jurisdiction over Bevagna and the Castello di Coccorone (Montefalco) from Spoleto to Foligno. These arrangements were reconfirmed in 1184.

The Counts of Antignano and Coccorone remained influential in the region and maintained a residence in Foligno. However, the Commune also had the support of Conrad of Urslingen, and enjoyed a considerable measure of self-rule over the city and contado. Costanza, the wife of Conrad of Urslingen, Duke of Spoleto (1177-98) stayed here in 1194 with the young grandson of Frederick I, the future Emperor Frederick II.

Urban Development

[Extension of the Duomo - 1133]

[Public palaces in ‘platea Communis’]

Any early indication of the existence of city walls around Foligno comes in a bull of 1138 (above), in which Pope Innocent II reserved for the bishop of Foligno rents from (inter alia) the bridges and gates of the city:

-

✴The earliest indication of the location of a city gate comes in the names of two ancient buildings:

-

•the “Hospitale Sanctae Mariae foris Portam”, which, according Ludovico Jacobilli, was documented in 1087 in the archives of the Abbazia di Sassovivo, albeit that this document no longer survives); and

-

•the church of "Sancte Marie extra portam vel in porta’" (Santa Maria outside the gate or at the gate), which was thus documented in 1207.

-

Thus, the church of Santa Maria (later Santa Maria Infraportas) was beside a gate that had been built between 1087 and 1207.

-

✴Another indication comes in the name of the church of San Pietro in Pusterna on what is now Via Saffi, just before the junction with what is now Via Mazzini. This church was first documented as San Pietro de Pusterla in 1213. Its name suggests that it stood by a small city gate or pusterla, possibly in a stretch of walls that ran along the latter street.

Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 93 and note 373) described a document in the archives of the Abbazia di Sassovivo dated 1217, which contains the earliest explicit mention of city walls. It described a house in Borgo San Leonardo, near the church of San Salvatore (, which was described as ‘extra murum civitatis’.

13th century

Pope Innocent III (1198-1216)

With the collapse of the power of Conrad of Urslingen in the Duchy of Soleto, Foligno submitted to Pope Innocent III in or shortly after 1198.

The institution in the city of the office of podestà at Foligno seems to date to 1198, and the first occupant of the post was probably a papal appointment.

Foligno was at war with Spoleto and Spello in 1200-1. Perugia rather than Innocent III acted as intermediary, staging the reconciliation of Spoleto and Foligno in the piazza in front of the Duomo of Perugia.

Bishop Anselmo degli Atti extended the Duomo of Foligno in 1201, just before he died. The portal on the new side façade contains reliefs of Innocent III and an emperor, presumably Otto of Brunswick, whom Innocent had just recognised as emperor-elect and who became the Emperor Otto IV.

In 1210, Diepold von Vohburg (whom Otto IV had appointed Duke of Spoleto in defiance of Innocent III) confirmed an Imperial privilege for Foligno. However, its towns of Bevagna and Coccorone seem to have fallen under direct Imperial control at about this time.

After Spoleto had almost totally destroyed Trevi in July 1214, Innocent III granted the ruins to Foligno, whose commune rebuilt the town and its Rocca.

Foligno (along with Amelia and Todi) supported Terni in its wars with Narni (and its ally Spoleto) in 1216-7.

Emperor Frederick II (1215-50)

There are indications that the Conti di Antignano e Coccorone were becoming restive from about 1219, probably at the instigation of Frederick II. Thus, for example, in 1219, Count Napoleone III took Marcellano near Todi in his name. Pope Honorius III had confirmed Napoleone III in his possession of Coccorone with the towers and the castles of the territory two years earlier. Yet in 1219, it was Frederick II who confirmed him in his ownership of the fortress of Santa Maria de Laurentio, near Bevagna.

His kinsman Rodolfo became Podestà of Foligno in that year. In 1222, Foligno (along with Gubbio and Nocera) went over Bertold of Urslingen, the brother of Rainald , the Imperial claimant to the Duchy of Spoleto. Honorius III excommunicated Bertold and sent troops to force him to withdraw.

In 1228, Rainald of Urslingen invaded the border areas of the Duchy of Spoleto, taking Foligno (along with Norcia, Cascia and Terni). The Conti di Antignano e Coccorone seem to have invited the imperial occupation of the Foligno, and Frederick II established the city as his base of operations. Bettona submitted to Foligno at this time in order to shake off the control of Assisi and Perugia.

Foligno briefly joined a defensive alliance that Perugia organised in 1238 after the excommunication of Frederick II. However, by 1240, the city had repudiated this alliance at the behest of Napoleone dei Conti di Antignano e Coccorone, and had sent emissaries out in advance to welcome Frederick II to the city. Bevagna, Coccorone and Bettona also declared for him, and they were among the towns and cities that sent representatives to the parliament that Frederick II summoned in the cathedral of San Feliciano.

Frederick II appointed Giacomo di Morra as Captain General of the Duchy of Spoleto, and he put in hand the building of a circuit of walls around Foligno and an imperial palace, so that the city would be equipped to act as a permanent centre of Ghibelline power in the Duchy. He then spent a few days at Coccorone before moving on to Viterbo, from where he threatened Rome. It was probably during this stay from 9th-13th February that this town changed its name to Montefalco, in honour of a Frederick’s gift of falcons to Napoleone dei Conti di Antignano e Coccorone. Imperial troops seem to have raided the Abbazia di Sassovivo outside Foligno in 1241.

In December 1243, the new Pope Innocent IV punished Foligno for its rebellion by transferring its bishop to Nocera Umbra. He formally excommunicated and deposed Frederick II at the Council of Lyons in 1245. The papal legate, Ranier iCapocci assembled an army from Perugia and Assisi to march on Spoleto, in the hope that this would provoke a Guelf uprising there. However, the new imperial rector, Marino d’ Eboli marshalled the local Ghibelline forces in the plain of Foligno, outside Spello, and they devastated the invaders, while the jubilant inhabitants of Spello hurled insults on the Guelfs from the safety of their walls. It was probably to this defeat that the chronicler Salimbene referred when he related how, "a single old woman from Foligno was able to drive ten Perugians off to prison with a simple cane".

The spectacular failure of the siege of Parma by Frederick II in the summer of 1247 brought hope to the Guelfs, and Ranier Capocci was able to persuade Spoleto to renounce the imperial cause. Among its rewards was the papal recognition of its ownership of Trevi, which had previously belonged to Foligno.

In 1249, Bevagna and Coccorone rebelled against Foligno. Bevagna destroyed a number of castles of Napoleone dei Conti Antignano e Coccorone, including Antignano itself, Santa Maria in Laurenzia and Ciriggiano. (The Castello di Torre del Colle, which also belonged to the Counts, still survives). In return Innocent granted Bevagna the right to elect its own podestà. However, the imperial general Tommaso d’ Aquino, Conte di Acerra retook both cities and sacked them.

Urban Development

[Left transept of the Duomo - 1201]

[Public administration in ‘platea Communis’ until ca. 1240]

Reconstruction of the so-called Palazzo Imperiale

From Vladimiro Cruciani, “Foligno: la Pietra Racconta”, (1990) Foligno

Frederick II appointed Rufino da Lodi as his legate to Foligno and charged him with the construction project that included the new city walls (described in my page on City Walls and Gates) and (apparently) the imperial palace. What we know of the subsequent history of this palace has to be deduced from documentation that relates to the period after the defeat of 1253:

-

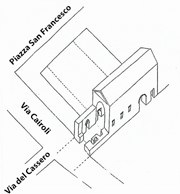

✴In 1255, Pope Alexander IV authorised the Friars Minor at San Matteo (a small church that was later incorporated into the church of San Francesco) to take possession of the adjacent ‘palatium curiae ... quod imperiale vocatur’ (i.e. the curial palace ... called imperial), which formed the nucleus of their new convent.

-

✴In 1256, a noblewoman, Margherita di Filippo Ofreduti, endowed the new foundation in her will, which was drawn up ‘in palatio quondam communis Fulginei ubi nunc est ecclesis fratrum minori’ (in the palace that once belonged to the Commune of Foligno, where now is the church of the Friars Minor).

Thus, the ‘palatium imperiale’ had also housed the administration of the Commune until 1253. The city administration then moved back to what became the ‘platea veteri Communis’, while the ‘palatium imperiale’ briefly became the ‘palatium curiae’, before its incorporation into the new Franciscan convent.

End of the Hohenstaufen Emperors (1250-68)

When Frederick II died suddenly in December 1250, the Conti di Antignano e Coccorone immediately submitted to the papacy. Some of them took up residence in Foligno, taking the names of De Comitibus and Rainaldi. Nevertheless, Innocent IV was reluctant to pardon Foligno, and the city prepared for war. Innocent IV refused to absolve Foligno and reinstate its bishop until Perugia agreed, and until it had paid damages to Spello and Trevi for damage that it had inflicted. He nevertheless warned Gubbio, Terni and Viterbo not to join in any fighting between Perugia and Foligno. The first mention of a Capitano del Popolo of Foligno dates to this period, and it is likely that this constitutional development marked an attempt to control factional warfare in the city.

When the death of Frederick’s son, Conrad in May 1254 prompted Innocent IV to leave Assisi for the Regno, Perugia and Assisi took advantage of his departure to avenge their defeat of 1246. They were given an excuse when Frederick’s illegitimate son, Manfred defeated Innocent IV at Foggia, prompting the Ghibelline Chiaravallesi at Todi to drive the Guelf Atti out of the city. Pandolfo of Anguillara assembled an army from Perugia, Assisi and Spoleto that suppressed the rebellion at Todi and then took Spello and laid siege to Foligno. He diverted the course of the Topino, thereby depriving the city of water.

After a siege of seven weeks, Foligno was forced to sign a peace treaty with Perugia on profoundly humiliating terms. They were required to demolish the walls, to fill in the canal and to refrain from building new fortifications. They were also required to readmit the Guelf exiles, to supply soldiers on request to Perugia and to accept a Podestà from Perugia for ten years. Trincia di Berardo Trinci was installed as the first Podestà under the new arrangements. The city also experienced a period of internal conflict. The Ghibelline Anastasio di Filippo degli Anastasi was named as Gonfaloniere di Giustizia at Foligno in 1260 in the aftermath of Montaperti. However, in 1261, Foligno and Spello each asked Perugia to supply a Podestà. Anastasio di Filippo degli Anastasi then held effective power throughout the period 1264-89, during which time he led the city’s revival after its humiliation by Perugia.

Angevins and the Papacy (1268-1305)

Foligno suffered from a severe earthquake in 1279, and work began in 1280 on a new circuit of walls bringing what had been suburbs into the walled city. Perugia demanded their demolition in early 1282, arguing that Foligno was contravening the treaty of 1254. Foligno invited the arbitration of Pope Martin IV (1281-5). Perugia refused to co-operate, and when Martin IV subjected Perugia and its ally Bettona to an interdict in 1283, the defiant Perugians burnt his effigy and those of the cardinals. The war initially went badly for Perugia and they agreed to a truce. They therefore received absolution in 1283, when the Curia moved to their city. Bettona was duly absolved in 1285. Foligno protected its position, despite the “Ghibelline” sympathies of Anastasio di Filippo degli Anastasi, by naming Martin IV as Podestà throughout the period 1284-6.

War with Perugia re-erupted in 1288 when Perugia formed an alliance with Todi and ravaged the contado of Foligno. Pope Nicholas IV sent Cardinals Benedict Caetani (the future Pope Boniface VIII) and Matteo Rosso II Orsini to arbitrate between the parties. Perugia remained defiant and the legates placed the city under interdict. Perugia responded by invading the contado of Foligno with its allies from Spello and Todi and taking the castles of Antignano and Torricella near Bevagna.

The people of Foligno underlined their desire for peace by appointing Corrado Trinci as Podestà in 1288, followed by his brother, Trincia in 1289. Corrado acted as Foligno’s delegate to Perugia in 1289, and managed to reach a settlement. Foligno submitted to Perugia in August 1289 and paid reparations in the following October. Nicholas IV withheld absolution until late 1290 and extracted a huge fine.

During the papal vacancy (1292-4), Perugia once more attacked Foligno. Although the cardinals went through the motions of excommunicating Perugia, they were sufficiently unconcerned that they moved the conclave to the city in October 1293, while hostilities were still in progress. Boniface VIII absolved Perugia in March, 1296.