Detail of the statue (1733) that is the focus of the

annual celebration of the feast of St Felician (24th January)

Duomo (on display only during the celebration)

The toponym civitas Fulginia implies that Foligno was the seat of a bishop, and would thus have had an episcopal church. The earliest surviving record of the use of this designation that I have been able to find dates to 496, when (as set out in my page on Early Christianity in Foligno) Pope Gelasius I wrote to three bishops of other dioceses (John of Spoleto, Cresconius of Todi; and a third bishop) directing them to investigate a legal claim against the recently-deceased Bishop Urbanus, who was referred to as “religiose recordationis Fulginatis civitatis antistitem” (the devoutly remembered bishop (or overseer) of civitas Fulginia).

The earliest use of the term that can be securely associated with the site of modern Foligno comes in two hagiographical sources that were both probably written at the Abbazia di Farfa in ca. 850:

-

✴The Legend of the Twelve Syrians (BHL 1620) records that SS Carpophorus and Abundius, were beheaded outside the walls of civitas Fulginia during the persecution of Christians undertaken by the Emperor Diocletian in 303.

-

✴The legend of St Felician (BHL 2846), which is discussed further below, has this bishop of Forum Flaminii begin his preaching career in ‘his city’, civitas Fulginia, during the reign of Pope Victor I (189-99). St Felician died in 250, while under arrest and en route for Rome, and was buried in a cemetery near civitas Fulginia (close to the site of the present Duomo).

It was to be another two centuries before civitas Fulginia appeared in any surviving secular document: Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 168) list seven such sources from 763 until 1035 in which the city is referred to as simply Fulginia (or variants thereof). The surviving documentary record of civitas Fulginia (or, sometimes, as civitas Santi Feliciani) begins in 1065.

Fulginia in the 9th Century

Bishop Domenico (documented in 850-3)

In 850, Pope Leo IV sent Bishop Domenico of Foligno as his representative at the Council of Pavia, which the Emperor Lothar I had convened. This suggests that he was of considerable standing in both papal and imperial circles. It was during a meeting with Bishop Tiberius of Berceto at this council that Domenico agreed to translate relics of St Abundius from Foligno to Berceto.

In 853, Domenico was one of 67 bishops who attended the synod in Rome that Leo IV had convened to deal with matters of Church discipline and, in particular, to secure the condemnation of the disobedient Anastasius, Cardinal of St Marcellus (later Antipope Anastasius Bibliothecarius). Domenico seems to have had a good relationship with Bishop Peter II of Spoleto, one of four bishops at this synod who had been sent by the Emperors Lothar I and Louis II:

-

✴In my page on SS Carpophorus and Abundius, I suggest that Domenico used the good offices of Peter II to secure the inclusion in the Legend of the Twelve Syrians (BHL 1620) of the lines that placed the martyrdom and burial of SS Carpophorus and Abundius at Foligno. This would have been necessary to explain to the people of Berceto how the relics of St Abundius that they had just received had found their way to Foligno in the first place, since the earlier Martyrology of Florus had SS Carpophorus and Abundius martyred at Spoleto.

-

✴In my page on St Felician, I suggest that Domenico commissioned the legend BHL 2846 shortly after. This probably followed his discovery of the relics of St Felician in the cemetery mentioned above and the construction of a martyrium (see below) in which to preserve them.

At the time that the legend of St Felician was written, civitas Fulginia (despite its name) does not seem to have been an episcopal centre: St Felician was the bishop of nearby Forum Flaminii. As discussed in my page on Foligno in the 5th - 8th centuries, the episcopal centre of Foligno was probably at San Valentino on Colle San Lorenzo. I suggest in my page on St Felician that the discovery of the relics and the commissioning of the legend were probably intended as part of a programme aimed at the elevation of Fulginia to episcopal status.

Martyrium of St Felician

Architectural remains that probably date to the 9th century and presumably came from this martyrium survive:

-

✴a column was re-used at the centre of the inner colonnade of the the loggia of the minor facade of the Duomo; and

-

✴ a cornice that was probably discovered during the restoration of the Duomo in 1903-4 was embedded in a wall of the crypt. [It is now in the Museo Diocesano].

According to Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 129), the remains from the martyrium constitute the only surviving material evidence for a cult site in civitas Fulginia, (as opposed to its suburbs) before the 11th century.

Santa Maria in Campis

The collection of architectural fragments (8th or 9th century) embedded into the back wall of the cloister of the present church of Santa Maria in Campis presumably came from an earlier church on this site.

The area around this church was occupied in Roman times and might have been the location of Roman Fulginia. In that case, one might imagine that it might have been the site of early Christian activity. However, these relatively late remains, which are broadly contemporary with those of the presumed martyrium of St Felician (above), constitute the only surviving evidence for the an early Christian cult site in the area.

It is also interesting to note there is no material evidence for any significant urban resettlement of the area after its apparent abandonment in the 5th century. Nor is there any evidence for a Christian cemetery in the area. This (in my view) makes it difficult to understand why this early church was built here - perhaps it belonged to a monastic community of which no trace survives ??

Fulginia in the 10th Century

A document (928) in the ‘Regestum Farfense’ (search on ‘fulginea’) in which Remedio da Bevagna made a donation to the abbey was executed “in Fulginea”. This suggests that Fulginia was a relatively important administrative centre at that time.

Bishop Benedetto (documented in 967 - 70)

Bishop Benedetto of Foligno attended a synod convened at Ravenna in 967 by the Emperor Otto I and Pope John XIII, at which the Exarchate of Ravenna was restored to John XIII, who, in return, agreed that Magdeburg would become a metropolitan see.

Theft of the Relics of St Felician (970)

Sigebert of Gembloux, in his ‘Vita Deoderici, Mettensis Episcopi’ (Life of Bishop Theodoric of Metz), recorded that Bishop Theoderic travelled to Italy in 970-2, with the Emperor Otto II. During this visit, he acquired a number of relics with which to enrich the Abbey of St Vincent, which he established in his diocese. These included relics of St Felician, which were ‘ipso intimo antro’ (in a very deep cavern) at ‘Fulinias [sic], castrum non procul a Spoleto’ (Fulginia, a castrum not far from Spoleto). There, on 4th October 970, the reluctant Bishop Benedetto, ‘multo cum fletu’ (with many tears), reluctantly released them into the hands of Theodoric’s representatives, Bertraus and Heriwardus, and they arrived at Metz on the 14th April, presumably in 971.

Civitas Fulginia in the 11th Century

As noted above, ‘Civitas Fulginia’ appeared in hagiographic sources in the 9th century. However, it continued to appear in legal documents as Fulginia or Fulginea, tout court. This changed in 1065 and 1067, when two such documents were notarised in Civitate Fulginea. This designation suggests that Fulginia was now universally recognised as a city with its own cathedral.

First Duomo of Foligno

Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at p. 129-30) dated the first phase of the construction of the present Duomo to the 11th century, and noted that what survives from this building is:

-

“... essentially:

-

-the [present] crypt and its oratory, together with the capitals of the columns that have been reused in it; and

-

-probably, some sculptural elements [now preserved in the crypt].

-

The church, in this phase, was already in the form a nave and two aisles, separated by columns, with the presbytery raised above the crypt and terminated in an apse” (my translation).

According to Ludovico Jacobilli (referenced below, at p. 101), it was dedicated to St John the Baptist: apparently St Felician (at popular request) and St Florentius were added to the dedication in 1133.

The first documentary evidence for this church comes in 1078, when Bishop Bonfiglio (1078-1115) made a number of donations to the canons of the ‘Fulginensis ecclesie’, evidenced by a document signed in the ‘domo canonicorum’ (canonica). This is also the earliest surviving archival record of the cathedral canons and their residence. The goods donated to them included two mills, one ‘in castro eiusdem ecclesie’ and the other near the pons Cesaris. This is the first time in the archival record that the ‘castrum’ at Foligno is explicitly linked to the Duomo, and it is interesting to note that it was large enough to enclose a mill. Thus, by this time, the Duomo stood at the heart of a relatively large walled enclosure that also contained the canonica and, presumably, the bishop’s palace (as well as the mill mentioned above). Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, at pp. 325-6, entry 124) described a stretch of wall behind Palazzo Trinci (which once faced Piazza del Grano, but which is now in the courtyard of the modern library) that might have constituted the northwestern edge of the castrum.

Counts of Uppello

This important family, which was based at Uppello, some 4 km east of Foligno, was of Lombard origin, albeit that the first securely documented member of it was Offredo di Monaldo, who documented the sale of property in 1067 in ‘Fulginea’. Silvestro Nessi (referenced below, at pp. 31-2) suggested that Monaldo, the father of Offredo, might well have been the Monaldo di Offredo who founded the Monastero di San Benedetto outside Gualdo Tadino in ca. 1006.

Abbazia di Sassovivo

In 1077, Ugolino and Oderisius, two of Monaldo’s sons, gave a piece of land some 2 km east of Uppello to Mainardo (who had belonged to a monastery near Gubbio) on which he built a hermitage. His church, which was dedicated as Santa Maria della Valle (or del Vecchio), was documented in 1082, in the document discussed above. The Abbazia di Santa Croce di Sassovivo here was first documented in 1084, when Mainardo formally accepted the patronage and protection of the ‘comite’ Ugolino and two of his brothers. It enjoyed the patronage of this family for more that a century, during which time it accumulated a vast patrimony.

Civitas Santi Feliciani

In 1082, the ‘comites’ Gualterius and Odorisius, sons of Ugolino, donated to Mainardo, provost Santa Maria Vecchio land ‘in loco qui dicitur Agellum, ubi prope est aedificata ecclesia et Civita Santi Feliciani ...’ (in a place called agellus, near which was built the church and city of St Felician). Guerrini and Latini (referenced below, at pp. 80-2) suggested that civitas Fulginia and civitas Santi Feliciani were alternative designations for the same city.

The transferred land near the Duomo was described as ‘in Comitatu Fulgineato’ (in the county of Foligno), which implies that the area administered by the Counts of Uppello. One wonders whether they had once owned the land upon which the adjacent Civitas Santi Feliciani had been established, and whether they had played a part of the construction of the first Duomo.

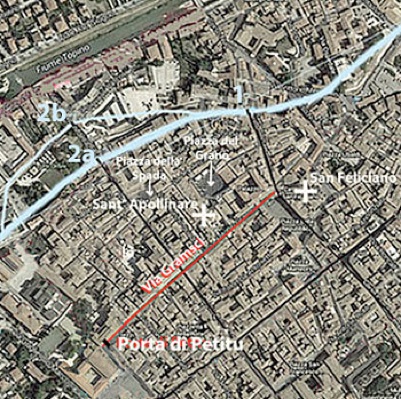

Urban Development

As noted in my page on Foligno in the 5th - 8th centuries, it seems likely that the settlement/resettlement of medieval Fulginia had begun in ca. 554 around the present site of Sant’ Apollinare. Paola Guerrini and Francesca Latini (referenced below, pp. 90) pointed out that this church is located in an area between Piazza della Spada and Piazza del Grano that has long been known as simply ‘il Borgo’. They suggested that:

-

“The fact that this area is simply identified as Borgo, without other names, suggests that this represented the first expansion of the city ... [The area is characterised by] a regular plan, articulated by an orthogonal road network whose main axis is Via dei Mercanti (now Via Gramsci), in which numerous large [Roman] blocks have been re-used at the bases of buildings and towers” (my translation).

They suggested (at p. 90) that the medieval city developed to the south of the original course of the Topino, between the Borgo and the hill on which the martyrium of St Felician and the episcopal castrum had been built. Since there is no evidence of city walls at this time, they further suggested that the settlements’ outer defences involved only “carbonarie”, ditches around the non-riverine part of the perimeter that were filled with water from the river.

An important feature of a settlement so close to the river must have been its bridges:

-

✴The pons Cesaris (marked 1 in the plan above) clearly existed in ca. 850, when it was mentioned in the legend of St Felician in order to locate the place of his burial. We might reasonably assume that the road between the bridge and the cemetery (now Via XX Settembre) also existed at this time.

-

✴Michele Faloci Pulignani, cited by Giovanni Dominici (referenced below, at p. 35), referred to a notarised document (10th century) that described the area of Isola Bella as “inter duos pontes” (between two bridges). This suggests (at least to me) that this island was created by a bifurcation in the original course of the Topino and that there were bridges across both of these branches in the 10th century (and perhaps before). These were almost certainly those marked 2 and 2a in the plan above. This implies the contemporary existence of the road connecting them (now Via San Giovanni dell’ Acqua), which met Via dei Mercanti (now Via Gramsci) at 90°.

As discussed in my page on the Location of Roman Fulginia, those scholars that believe that Roman Fulginia was on the same site as medieval Foligno generally believe that the bridges 1 and 2 date to Roman times.

Read more:

P. Guerrini and F. Latini, “Foligno: Dal Municipium Romano alla Civitas Medievale: Archeologia e Storia di una Città Umbra”, (2012) Spoleto

S. Nessi, “I Trinci, Signori di Foligno”, (2006) Foligno

G. Dominici, “Fulginia: Questioni sulle Antichità di Foligno”, (1935) Verona

L. Jacobilli, “Vite de' Santi e Beati di Foligno”, (1628)

Return to History of Foligno